User talk:Thomas Wright Sulcer/sandbox: Difference between revisions

imported>Thomas Wright Sulcer (Restoring pictures; still need to tighten this article, perhaps split it) |

imported>Thomas Wright Sulcer (Disabled Nexrad hurricane picture; found one already in Citizendium of a hurricane) |

||

| Line 111: | Line 111: | ||

Spinoza would argue that since the people in the picture could push the rock, possibly smashing it, the rock wouldn't exist ''in itself''.<ref name=tws10dec01/> Rather, the rock's existence depended on what the two people did or didn't do. So, the rock, by itself, wasn't enough to fully explain things. The two people were part of the explanation. One couldn't explain the idea of the rock without explaining other things that might influence the rock, such as the people. | Spinoza would argue that since the people in the picture could push the rock, possibly smashing it, the rock wouldn't exist ''in itself''.<ref name=tws10dec01/> Rather, the rock's existence depended on what the two people did or didn't do. So, the rock, by itself, wasn't enough to fully explain things. The two people were part of the explanation. One couldn't explain the idea of the rock without explaining other things that might influence the rock, such as the people. | ||

[[Image:Hurricane Rita NEXRAD radar animation.gif|thumb|280px|right|alt=An animated file the colorized radar version of a hurricane|Hurricane Rita could emerge from the [[Gulf of Mexico]] and possibly blow over the rock.]] | <!--- [[Image:Hurricane Rita NEXRAD radar animation.gif|thumb|280px|right|alt=An animated file the colorized radar version of a hurricane|Hurricane Rita could emerge from the [[Gulf of Mexico]] and possibly blow over the rock.]]---> | ||

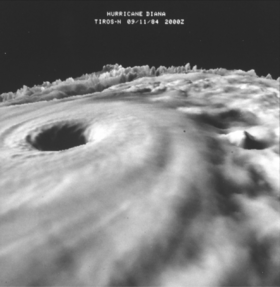

[[Image:Hurricane Diana.png|thumb|280px|right|alt=An animated file the colorized radar version of a hurricane|Hurricane Diana could possibly topple the rock.]] | |||

Spinoza thought the two people and the rock could be moved by other forces, such as a [[hurricane]] which might blow people away from the rock or a [[meteor]] which might tumble from the sky and squish them. These things could happen. For Spinoza, it didn't make sense to try to explain the rock-as-substance without trying to explain things which might affect the rock, such as people, hurricanes, or meteors. That is, the rock, by itself, wasn't all there was to the concept of ''[[Substance theory|substance]]'', but substance was bigger. | Spinoza thought the two people and the rock could be moved by other forces, such as a [[hurricane]] which might blow people away from the rock or a [[meteor]] which might tumble from the sky and squish them. These things could happen. For Spinoza, it didn't make sense to try to explain the rock-as-substance without trying to explain things which might affect the rock, such as people, hurricanes, or meteors. That is, the rock, by itself, wasn't all there was to the concept of ''[[Substance theory|substance]]'', but substance was bigger. | ||

Revision as of 13:38, 16 February 2010

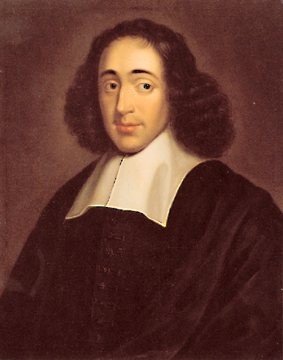

The philosophy of Spinoza is a systematic, logical, rational philosophy developed by him in the seventeenth century in Europe.[1][2][3] It's a system of ideas built from basic building blocks with an internal consistency with which Spinoza tried to answer life's major questions and in which he proposed that "God exists only philosophically."[3][4] He was heavily influenced by thinkers such as Descartes[5] and Euclid[4] and Thomas Hobbes[5] as well as theologians in the Jewish philosophical tradition such as Maimonides,[5] but his work was in many respects a departure from the Judeo-Christian tradition. Many of Spinoza's ideas continue to vex thinkers today and many of his principles, particularly regarding the emotions, have implications for modern approaches to psychology. Even top thinkers have found Spinoza's "geometrical method"[3] difficult to comprehend. Goethe admitted that he "could not really understand what Spinoza was on about most of the time."[3] The Ethics contains unresolved obscurities and has a forbidding mathematical structure modeled on Euclid's geometry.[4] But his philosophy attracted believers such as Albert Einstein.[6] and much intellectual attention.[7][8][9][10][11]

A logical geometric method

Spinoza's philosophy can be compared to an effort to build a dictionary from scratch, starting with a definition of the word the, and using rules to build an entire vocabulary from basic principles. Spinoza's method paralleled the geometrical method of mathematicians such as Descartes[12] or Euclid who built geometry from basic theorems, and using the basic theorems to deduce more complex theorems. Descartes defined method as "reliable rules which are easy to apply, and such that if one follows them exactly, one will never take what is false to be true or fruitlessly expend one's mental efforts, but will gradually and constantly increase one's knowledge until one arrives at a true understanding of everything within one's capacity." Spinoza's philosophy is a system of thought, then, that is heavily dependent on having correct initial assumptions as well as logical inferences about them. It's possible, then, that if the fundamental assumptions that Spinoza made were wrong, or if the logical deductions were wrong, then the entire philosophy could be mistaken. This is one of the risks of any systematic philosophy in which ideas depend on other ideas. Still, Spinoza's philosophy continues to intrigue scholars as well as affect new developments in philosophy and science.

Substance

The term substance comes from that which stands underneath. Spinoza thought there was only one substance. His understanding:

| “ | By substance I mean that which is in itself, and is conceived through itself: in other words, that of which a conception can be formed independently of any other conception.[13] | ” |

Substance, for Spinoza, is something which is "in itself". It doesn't depend on anything else. It exists. It doesn't need anything else to exist. It's just there.

In addition to the concept of substance, a second basic building block is the idea of causation. This is the idea that causes cause effects. Spinoza wrote: "From a given definite cause an effect necessarily follows; and, on the other hand, if no definite cause be granted, it is impossible that an effect can follow."[14] No cause? Then no effect happens. No effect? Then there was no cause. For Spinoza, the world is a giant cause-and-effect relations like a giant billiards table. A ball in motion hits a second ball, and the second ball moves as a result. The first ball causes the movement of the second. And the second one moving is the effect of being struck by the first. If the second didn't move, then it didn't get bumped by the first. The cause-and-effect relation is fundamental for understanding Spinoza's philosophy.

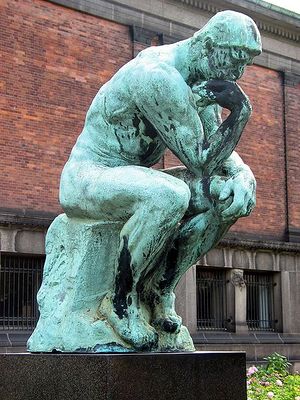

Spinoza, then, took these two basic ideas: substance and causation, and put them together to build bigger conclusions. If substance is what exists in itself and if the world is characterized by cause-and-effect relations, then is the rock substance? It exists. It's hard. It's huge. It's there. But suppose the two people in the picture got a lever and pushed it over, then the rock might tumble and break into bits.

Spinoza would argue that since the people in the picture could push the rock, possibly smashing it, the rock wouldn't exist in itself.[13] Rather, the rock's existence depended on what the two people did or didn't do. So, the rock, by itself, wasn't enough to fully explain things. The two people were part of the explanation. One couldn't explain the idea of the rock without explaining other things that might influence the rock, such as the people.

Spinoza thought the two people and the rock could be moved by other forces, such as a hurricane which might blow people away from the rock or a meteor which might tumble from the sky and squish them. These things could happen. For Spinoza, it didn't make sense to try to explain the rock-as-substance without trying to explain things which might affect the rock, such as people, hurricanes, or meteors. That is, the rock, by itself, wasn't all there was to the concept of substance, but substance was bigger.

It's possible to work outwards, past the earth, past the solar system, past the universe, to the edge of the galaxy, and reason that since everything in the universe could possibly affect the rock, that it was all one substance.

Spinoza wrote: "There cannot exist in the universe two or more substances having the same nature or attribute."[15] The rock wasn't one substance; and the persons weren't a second separate substance. Rather, the rock and the people could affect each other. The people could smash the rock. And rock could tumble on the people. Therefore, the rock and people were part of the same substance.[16] Spinoza reasoned everything in the universe was essentially one substance.

Suppose, then, there is only one substance called the universe. Is it possible for a supernatural being called God to exist outside this universe, but still be able to manipulate things inside the universe? By Spinoza's own reckoning, this wasn't possible. If there were two separate substances, one substance called the universe and a second substance called God, then, because they were separate, the substance called God would be unable to reach in and change things in the substance called the universe. If God could reach into the universe and make changes, then they weren't separate.[17] Rather, God and the universe would be the same substance. God causing things like a hurricane meant that God was part of the universe, in Spinoza's view. Accordingly, Spinoza concluded that God and the universe were not separate substances, but that God and the universe were the same substance.[2][18]

Building from this logic, Spinoza concluded that substance necessarily exists. It can't be made by anything else. Substance can't be born, live, and die. Rather, substance must exist always. If substance behaved like a human or a finite thing then there would be logical problems with the understanding of substance as well as cause-and-effect.

This thinking is expressed scientifically in concepts such as the conservation of matter or the conservation of energy. The rock can be broken into bits, toppled by gravity, hammered into sand, melted, and converted into energy, but it's impossible to make anything totally disappear in a closed system. It will always be there in some form or shape. In Spinoza's world, there are no magicians who can make a rabbit spontaneously appear out of a hat, or disappear totally in a poof of smoke.

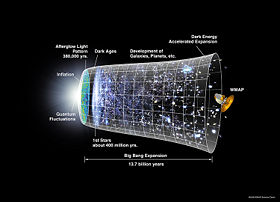

Substance, then, is described as self-caused. It causes itself. It isn't caused by anything else, otherwise it wouldn't be a true substance. Since substance can't have been born, and can't die, then as a result, the universe has always been here. There was no moment when the universe was created. And there won't ever come a time when it disappears.[20] Spinoza would wonder what happened before the Big Bang and argue that it wasn't merely nothingness, but somethingness. Time extends forever, infinitely, backwards and forwards, so there never was a beginning moment, and there never will be a final moment. Further, the universe extends infinitely outwards into space; there is no boundary, ever. It keeps going and going and going forever. Spinoza wrote: "Every substance is necessarily infinite."[19][2]

According to Spinoza, as humans, we're born, we live, we die. We live in houses with walls. We think in terms of finite existence, and it's difficult for us to imagine the universe extending forever in space and time, or to imagine a house without walls.[21]

There's the universe. And there's the idea of the universe. The physical universe is a solid thing with mass and form and shape and energy which exists in what philosophers sometimes call extension; in addition, there's the idea of extension of what philosophers sometimes call Thought. Spinoza considered that both extension and thought were two attributes of everything, of the universe, of God, which humans were able to perceive, since we can sense things physically and we can think about thinking about things. But Spinoza thought there were not just two attributes of extension and thought, but infinitely many attributes,[22] although humans can't conceive what the third, fourth, or any other attributes are. Were the attributes of extension and thought separate substances? No, wrote Spinoza; rather, extension and thought were both attributes of one single solitary infinite undivisible substance.[23]

From his reasoning, Spinoza establishes that God is the only substance in the universe, or in Nature, or in the world. Spinoza wrote: "Whatsoever is, is in God, and without God nothing can be, or be conceived."[24] But philosophers today debate the meaning of this phrase; some think that Spinoza meant that God was a supernatural element within Nature, existing possibly like water inside a sponge, while others think Spinoza thought that God and Nature were exactly the same thing, like a wet sponge.[2]

Necessity and determinism

Now, if God's all there is,[25] and causes-cause-effects, then God causes everything,[26] according to Spinoza. If a cause happens, the effect must follow, and by this logic Spinoza comes to the conclusion that everything is determined. If the universe or nature is like a giant billiards table with balls bumping other balls, and there is no God separate from the table with a cue stick causing things to happen, then everything that happens had to happen, and couldn't have happened otherwise. This includes not only things happening, but the ideas-of-things happening. According to Spinoza, it was fated to happen that you would be sitting where you are right now, at this time, reading this article on Wikipedia, and thinking what you're thinking right now. It couldn't have happened otherwise. It was destiny.[2] Surprisingly, Spinoza did believe in free will but in a different sense.

Spinoza thought of specific things such as humans and rocks and billiard balls as finite things or what he called modes.[27] Particular things exist with a limited extension and duration; finite modes "come into being at a certain point in time and cease to exist at a certain point in time."[27] Finite things can be born, live and die. In extension, they're bodies or things. In thought, they're minds or ideas. Particular things are part of nature or the universe or God. And there are infinitely many bodies and ideas as well as possible bodies and ideas. Particular things and ideas are in God, but they're not the same thing as God. But particular things exist in long chains of cause-and-effect. Spinoza wrote:

| “ | Every singular thing, or any thing which is finite and has a determinate existence, can neither exist nor be determined to produce an effect unless it is determined to exist and produce an effect by another cause, which is also finite and has a determinate existence; and again, this cause also can neither exist nor be determined to produce an effect unless it is determined to exist and produce an effect by another, which is also finite and has a determined existence, and so on, to infinity."[27] | ” |

Each billiard ball in the infinitely large billiards table called the universe bounces as a result of infinitely many causes-and-effects ricochets. The universe has particular things in it such as creatures and rocks and planets and meteors and dust storms and waterfalls and humans, and has ideas of these things, but they exist temporarily with a finite duration in time and place. All this stuff, nevertheless, is part of the eternal and infinite universe.

God is in charge in the sense that there isn't another being or substance interfering; but "God is a free cause," in his view.[28] Nothing pushes God around. Nothing forces God to do this or that. There is no supernatural drill sergeant other than God. Spinoza sees "true freedom" and "being the first cause" as essentially the same thing.[28] Spinoza didn't think supernatural events were possible which violated natural law. So-called miracles such as Moses parting the waters of the Red Sea or Jesus raising dead people back to life were impossible, in Spinoza's view. Instead, he saw miracles as events which humans didn't fully understand but which could have been explained with rational causes. For Spinoza, the ability of the Israelites to cross the Red Sea had another explanation which was rational and which agreed with natural laws, but humans don't know what it is.[29]

There has been philosophical debate about whether Spinoza was a pantheist or atheist. But clearly Spinoza's God is different from a Judeo-Christian conception of a transcendent Being distinct from the world who is an all-knowing, sometimes benevolent and sometimes wrathful judge. Spinoza argues that God doesn't have some purpose for mankind which is rewarded if people work towards this goal, or punished if they don't. There is no teleology.[30]

How do things and thoughts interrelate? Spinoza thought there was a one-to-one correspondence between things and the ideas of these things. So, there is a relation between a rock and the idea of that rock. But Spinoza goes further. He wrote:

| “ | The order and connection of ideas is the same as the order and connection of things."[31] | ” |

Suppose there is a rock. Suppose, further, there is a window. The relation between these things is: a hurled rock can break a window. But Spinoza says this relation can correspond to an order of thought: that the idea of a hurled rock can lead logically to the idea of a broken window. It's called the doctrine of parallelism. Ordered stuff in the world of substance can be expressed as extension or as thought, and the two orders parallel each other. It's like both extension and thought are one and the same thing, but expressed in two different ways.

One important caveat is that thoughts don't cause physical events, in and of themselves. For example, the thought "I'm going to throw that rock through that window," in itself, doesn't break the window. It's just a thought. But what can break the window? In a person's mind, there may be a physical alignment of electrons and nerve memories which forms the impulse to motivate a person to pick up a rock and hurl it at a window. This physical alignment of electrons can cause the physical event of a broken window. The doctrine of parallelism says that there is a correspondence between the thought of hurling a rock at a window and the extension principle of a physical alignment of electrons in the brain about such an activity. Thoughts, however, can cause other thoughts; physical events, as well, can cause other physical events.

This leads to Spinoza's answer to the famous mind-body problem. How can an ethereal nebulous fog-like can't-be-touched thought cause something physical and tangible and can-be-touched thing like a human arm to lift? How can a thought cause a thing to move? This puzzle has bothered philosophers throughout history. Descartes suspected that there was an area in the brain called the pineal gland in which thoughts and actions affected each other, but Descartes never specified how this happened.[32] Spinoza disagreed. Spinoza said the "thought of lifting an arm" and "lifting an arm" were two different ways of expressing the same thing. The physical alignment of electrons guides the human to raise an arm; the electrons move, signals are sent from the brain to the arm, the arm lifts. It's the physical alignment of electrons which causes the physical arm to move. And, by the parallel doctrine, it's possible have the thought of "let's lift the arm" causing the thought of "the arm is lifted" to happen. It's two different ways of expressing the same thing: lifting the arm.

So, what is a human mind? Spinoza says it's the "idea of a particular body." A human mind is one of infinitely many ideas that make up the "infinite intellect of God." When a human body exists, the human mind exists too. And in the same way that billiard balls are connected to other billiard balls, which are in turn connected to the walls of the billiards table, to the room that the billiards table is in, connected to the outdoors, to the planet Earth, to the solar system and universe, and to all physical things everywhere––in the same way––the ideas in the human mind are connected to other ideas, which are in turn connected to other ideas, connected to infinitely other ideas that form the "infinite intellect of God."

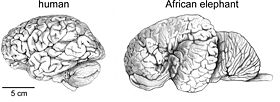

Why are humans smarter than rocks? Or animals? Or beavers? Or elephants? Spinoza explains:

| “ | "The human mind is capable of perceiving a great number of things, and is so in proportion as its body is capable of receiving a great number of impressions. The idea, which constitutes the actual being of the human mind, is not simple, but compounded of a great number of ideas."[33] | ” |

But, according to Spinoza, all minds are not alike. Minds vary; so do things. Some minds have more complexity and excellence and power. Others don't. Bodies can have different shapes, sizes, divisibility and "motion and rest".[34] Things don't move unless they're determined to move by something else; once moving, they keep moving until stopped by something else. This is an essential proposition of physics which Spinoza agreed with. So, what distinguishes one body from another is the varying proportions of motion and rest, speed and slowness. Spinoza thought there was a "certain fixed manner" in which bodies "communicate their motions to each other"; Spinoza called it the "ratio of motion and rest."[35] A body gets its "integrity" and "individuality" by having its parts relate to each other in the same general way. Human bodies are extraordinarily complex. They can act on other bodies, and be acted on by other bodies, in countless ways.[36]

Is there life after death? Spinoza thought there wasn't. Descartes thought that a soul, being a mental state separate from the physical body, could survive bodily death; but Spinoza, who thought that the mind and the body were different ways of conceiving the same thing, would disagree. When the body dies, the mind dies too.

When the body feels good, the mind feels pleasure; when the body is injured, the mind feels pain. A single idea can be complex, composed of a great many smaller ideas, in the same way that the human body is made of a great number of smaller bodily parts. We may not necessarily be aware of all bodily events, but conscious of only a few things. It's possible to perceive external things too.

Further, a body can perceive not only itself, but external things. The mind immediately focuses on the body, and things that affect the body can help the mind perceive external bodies. The mind only perceives external objects when they affect the body. So, the human eye sees the singer holding a microphone, and this image enters the eyes and causes a change in the human body, and, as a result, there's some sense of the external object as well as an idea about this external body.

But this information is limited.[37] Spinoza thought that our ideas of external bodies indicated the condition of our own bodies more than the nature of the external bodies.[38] So our information about the Swiss singer is imperfect, limited, a guess which is partial and relative information.

Spinoza thought that ideas involve mental activity; they weren't static pictures in the mind or image-objects.[39] Every thought required some activity of the mind. To have an idea of a red ball requires thinking that the ball is red.

Ideas are true if there's an extrinsic relation between the idea and its object, that is, if the idea represents it as being. Spinoza calls this "the agreement of the idea with its object".[40] A false idea doesn't have this relation. So the difference between a true idea and a false idea doesn't depend on the content of the idea itself, but only whether it faithfully represents this correspondence. So, in a sense, all ideas in the infinite intellect of God are true, because all ideas relate to something;[41] but all ideas in the human mind, however, are not necessarily true.[42]

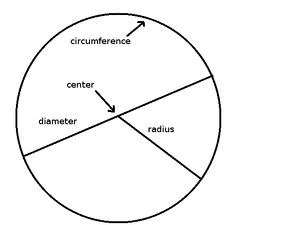

Spinoza felt that when we have an idea in our head which "encompasses perfect and complete knowledge of its object," that is, the idea has all of the same properties that the real thing has, then the idea was adequate and was a reliable marker of truth.[43] For example, the adequate idea of a circle is one in which we have all of the properties that characterize a circle, that is, all the radii are the same distance from a center point. Adequacy of ideas is bound up with causal understanding. Spinoza wrote to Tschirnhaus: "...the idea or definition of the thing should express its efficient cause." So, the adequate truthful definition of a circle is all radii equally distant from a center point and not extra irrelevant junk like the triangle inside the circle (see diagram), or the circle's thickness which constitute "inadequate ideas" which are "mutilated" and "confused."[44] Inadequacy is ignorance or missing knowledge like "conclusions without premises."[45] When we don't fully understand the causes behind an idea, we make mistakes about whether the ideas are necessary or contingent.

True ideas agree with their object; adequate ones agree with the "nature of the idea in itself." So there's some overlap between a true idea and an adequate idea. But since God is "infinite intellect," all of God's ideas are adequate.[46] But the human mind, in contrast, can not hold infinite ideas and causes. The best humans can hope for is partial knowledge. We can't know the infinite series of chains of ideas leading up to why something happened; only God can know this. However, we can get an adequate idea of a few of the proximate causes of a specific event, and in that way, build on those adequate ideas to create other adequate ideas, and in this way, we can understand some things to a limited extent.[47] Adequate ideas follow from other adequate ideas; knowledge of a triangle can follow from knowledge from geometry. But generally we don't know most things adequately. When things affect us, we're aware of how we're affected, but we're generally ignorant of the causes of these impressions.[48] We focus on drinking a cool glass of water but don't usually understand details about how the water sustain's our body's existence. Our minds are sensory reflections of what our bodies feel.

But the best form of knowledge is to know things by the logical principles of Thought. This knowledge mirrors the cause-and-effect principles which apply to the physical world. While most things that affect people are random and haphazard, there are some things which it's possible for people to understand adequately to begin with, such as common notions such as shape, size, divisibility, and mobility.[49] These things are the first chances for the mind to have certain ideas that are determined internally from its own resources rather than from random experience. And, it's possible to build other adequate ideas from these initial adequate ones.[50]

What Spinoza thought was best for people was to have longer and longer chains in their minds of adequate ideas, that is, ideas which corresponded accurately with reality, and as much as possible, to have these logically connected correct ideas direct human action. Such a person is active and not passive,[2] and has a measure of power over his or her life to get things needed, to make good decisions, to survive and prosper. When the mind grasps an idea entirely, adequately, then the mind is active; but if the idea is partially caused by some external source, then the idea is polluted and the mind is passive. An individual actively passively is really re–acting not acting.

Still, even though a human uses his or her mind actively, not passively, from the point of view of Nature or God, this person doesn't have free will, since everything that happens to him or her had to happen of necessity;[51] but, from the point of view of the individual human, he or she can strive to get a greater power to manipulate things for advantage.

The Emotions

What are emotions? They happen when external events affect us, and when we have confused ideas about these events. In his view, emotions reflect a "passivity of the soul."[52] The body's power is increased or diminished. Emotions are bodily changes plus ideas about these changes which can help or hurt a human.[53] When the bodily changes are caused primarily by external forces or by a mix of external and internal forces, the person is passive. It's much better for a person, himself or herself, to cause the bodily changes, and when this happens the person is active, and Spinoza describes the ideas as adequate. Spinoza defines each emotion in simple terms, based on the cause-and-effect ideas in his logical system. The emotions can be grouped generally into ones which causing either pleasure or pain, and all spring from desire.

Definitions of each emotion

- Desire is the actual essence of man, in so far as it is conceived, as determined to a particular activity by some given modification of itself.[52]

- Pleasure is the transition of a man from a less to a greater perfection.[52]

- Pain is the transition of a man from a greater to a less perfection.[52]

- Wonder is the conception (imaginatio) of anything, wherein the mind comes to a stand, because the particular concept in question has no connection with other concepts.[52]

- Contempt is "the conception of anything which touches the mind so little, that its presence leads the mind to imagine those qualities which are not in it rather than such as are in it."[52]

- Love is pleasure, accompanied by the idea of an external cause.[52]

- Hatred is pain, accompanied by the idea of an external cause.[52]

- Inclination is pleasure, accompanied by the idea of something which is accidentally a cause of pleasure.[52]

- Aversion is pain, accompanied by the idea of something which is accidentally the cause of pain.[52]

- Devotion is love towards one whom we admire.[52]

- Derision is pleasure arising from our conceiving the presence of a quality, which we despise, in an object which we hate.[52]

- Hope is an inconstant pleasure, arising from the idea of something past or future, whereof we to a certain extent doubt the issue.[52]

- Fear is an inconstant pain arising from the idea, of something past or future, whereof we to a certain extent doubt the issue.[52]

- Confidence is pleasure arising from the idea of something past or future, wherefrom all cause of doubt has been removed.[52]

- Despair is pain arising from the idea of something past or future, wherefrom all cause of doubt has been removed.[52]

- Joy is pleasure accompanied by the idea of something past, which has had an issue beyond our hope.[52]

- Disappointment is pain accompanied by the idea of something past, which has had an issue contrary to our hope.[52]

- Pity is pain accompanied by the idea of evil, which has befallen someone else whom we conceive to be like ourselves.[52]

- Approval is love towards one who has done good to another.[52]

- Indignation is hatred towards one who has done evil to another.[52]

- Partiality is thinking too highly of anyone because of the love we bear him.[52]

- Disparagement is thinking too meanly of anyone, because we hate him.

- Envy is hatred, in so far as it induces a man to be pained by another's good fortune, and to rejoice in another's evil fortune.[52]

- Sympathy (misericordia) is love, in so far as it induces a man to feel pleasure at another's good fortune, and pain at another's evil fortune.[52]

- Self-approval is pleasure arising from a man's contemplation of himself and his own power of action.[52]

- Humility is pain arising from a man's contemplation of his own weakness of body or mind.[52]

- Repentance is pain accompanied by the idea of some action, which we believe we have performed by the free decision of our mind.[52]

- Pride is thinking too highly of one's self from self-love.[52]

- Self-abasement is thinking too meanly of one's self by reason of pain.[52]

- Honour (gloria) is pleasure accompanied by the idea of some action of our own, which we believe to be praised by others.[52]

- Shame is pain accompanied by the idea of some action of our own, which we believe to be blamed by others.[52]

- Regret is the desire or appetite to possess something, kept alive by the remembrance of the said thing, and at the same time constrained by the remembrance of other things which exclude the existence of it.[52]

- Emulation is the desire of something, engendered in us by our conception that others have the same desire.[52]

- Thankfulness or Gratitude is the desire or zeal springing from love, whereby we endeavour to benefit him, who with similar feelings of love has conferred a benefit on us.[52]

- Benevolence is the desire of benefiting one whom we pity.[52]

- Anger is the desire, whereby through hatred we are induced to injure one whom we hate.[52]

- Revenge is the desire whereby we are induced, through mutual hatred, to injure one who, with similar feelings, has injured us.[52]

- Cruelty or savageness is the desire, whereby a man is impelled to injure one whom we love or pity.[52]

- Timidity is the desire to avoid a greater evil, which we dread, by undergoing a lesser evil.[52]

- Daring is the desire, whereby a man is set on to do something dangerous which his equals fear to attempt.[52]

- Cowardice is attributed to one, whose desire is checked by the fear of some danger which his equals dare to encounter.[52]

- Consternation is attributed to one, whose desire of avoiding evil is checked by amazement at the evil which he fears.[52]

- Courtesy or deference (Humanitas seu modestia), is the desire of acting in a way that should please men, and refraining from that which should displease them.[52]

- Ambition is the immoderate desire of power.[52]

- Luxury is excessive desire, or even love of living sumptuously.[52]

- Intemperance is the excessive desire and love of drinking.[52]

- Avarice is the excessive desire and love of riches.[52]

- Lust is desire and love in the matter of sexual intercourse.[52]

Spinoza didn't think highly of the Christian virtue of humility. And love could happen between a man and a woman such as romance or between a person and a bar of chocolate.

Propositions about emotions

Spinoza then linked his study of emotions into a series of propositions about how they related to human problems and play out in the human mind and in interactions between people and between persons and nature. Some ideas have been expressed in modern sciences such as psychology with its use of notions such as the principle of association and form the basis for theories such as cognitive dissonance. These propositions have a wide array of uses; for example, it can explain why powerful emotions such as extreme love can switch over to extreme hate. Here are the propositions:

- I. Our mind is in certain cases active, and in certain cases passive. In so far as it has adequate ideas it is necessarily active, and in so far as it has inadequate ideas, it is necessarily passive.

- II. Body cannot determine mind to think, neither can mind determine body to motion or rest or any state different from these, if such there be.

- III. The activities of the mind arise solely from adequate ideas; the passive states of the mind depend solely on inadequate ideas.

- IV. Nothing can be destroyed, except by a cause external to itself.

- V. Things are naturally contrary, that is, cannot exist in the same object, in so far as one is capable of destroying the other.

- VI. Everything, in so far as it is in itself, endeavours to persist in its own being.

- VII. The endeavour, wherewith everything endeavours to persist in its own being, is nothing else but the actual essence of the thing in question.

- VIII. The endeavour, whereby a thing endeavours to persist in its being, involves no finite time, but an indefinite time.

- IX. The mind, both in so far as it has clear and distinct ideas, and also in so far as it has confused ideas, endeavours to persist in its being for an indefinite period, and of this endeavour it is conscious.

- X. An idea, which excludes the existence of our body, cannot be postulated in our mind, but is contrary thereto.

- XI. Whatsoever increases or diminishes, helps or hinders the power of activity in our body, the idea thereof increases or diminishes, helps or hinders the power of thought in our mind.

- XII. The mind, as far as it can, endeavours to conceive those things, which increase or help the power of activity in the body.

- XIII. When the mind conceives things which diminish or hinder the body's power of activity, it endeavours, as far as possible, to remember things which exclude the existence of the first-named things.

- XIV. If the mind has once been affected by two emotions at the same time, it will, whenever it is afterwards affected by one of the two, be also affected by the other.

- XV. Anything can, accidentally, be the cause of pleasure, pain, or desire.

- XVI. Simply from the fact that we conceive, that a given object has some point of resemblance with another object which is wont to affect the mind pleasurably or painfully, although the point of resemblance be not the efficient cause of the said emotions, we shall still regard the first-named object with love or hate.

- XVII. If we conceive that a thing, which is wont to affect us painfully, has any point of resemblance with another thing which is wont to affect us with an equally strong emotion of pleasure, we shall hate the first-named thing, and at the same time we shall love it.

- XVIII. A man is as much affected pleasurably or painfully by the image of a thing past or future as by the image of a thing present.

- XIX. He who conceives that the object of his love is destroyed will feel pain; if he conceives that it is preserved he will feel pleasure.

- XX. He who conceives that the object of his hate is destroyed will feel pleasure.

- XXI. He who conceives, that the object of his love is affected pleasurably or painfully, will himself be affected pleasurably or painfully; and the one or the other emotion will be greater or less in the lover according as it is greater or less in the thing loved.

- XXII. If we conceive that anything pleasurably affects some object of our love, we shall be affected with love towards that thing. Contrariwise, if we conceive that it affects an object of our love painfully, we shall be affected with hatred towards it.

- XXIII. He who conceives, that an object of his hatred is painfully affected, will feel pleasure. Contrariwise, if he thinks that the said object is pleasurably affected, he will feel pain. Each of these emotions will be greater or less, according as its contrary is greater or less in the object of hatred.

- XXIV. If we conceive that anyone pleasurably affects an object of our hate, we shall feel hatred towards him also. If we conceive that he painfully affects the said object, we shall feel love towards him.

- XXV. We endeavour to affirm, concerning ourselves, and concerning what we love, everything that we conceive to affect pleasurably ourselves, or the loved object. Contrariwise, we endeavour to negative everything, which we conceive to affect painfully ourselves or the loved object.

- XXVI. We endeavour to affirm, concerning that which we hate, everything which we conceive to affect it painfully; and, contrariwise, we endeavour to deny, concerning it, everything which we conceive to affect it pleasurably.

- XXVII. By the very fact that we conceive a thing, which is like ourselves, and which we have not regarded with any emotion, to be affected with any emotion, we are ourselves affected with a like emotion (affectus).

- XXVIII. We endeavour to bring about whatsoever we conceive to conduce to pleasure; but we endeavour to remove or destroy whatsoever we conceive to be truly repugnant thereto, or to conduce, to pain.

- XXIX. We shall also endeavour to do whatsoever we conceive men to regard with pleasure, and contrariwise we shall shrink from doing that which we conceive men to shrink from.

- XXX. If anyone has done something which he conceives as affecting other men pleasurably, he will be affected by pleasure, accompanied by the idea of himself as cause; in other words, he will regard himself with pleasure. On the other hand, if he has done anything which he conceives as affecting others painfully, he will regard himself with pain.

- XXXI. If we conceive that anyone loves, desires, or hates anything which we ourselves love, desire, or hate, we shall thereupon regard the thing in question with more steadfast love, &c. On the contrary, if we think that anyone shrinks from something that we love, we shall undergo vacillation of soul.

- XXXII. If we conceive that anyone takes delight in something, which only one person can possess, we shall endeavour to bring it about that the man in question shall not gain possession thereof.

- XXXIII. When we love a thing similar to ourselves we endeavour, as far as we can, to bring about that it should love us in return.

- XXXIV. The greater the emotion with which we conceive a loved object to be affected towards us, the greater will be our complacency.

- XXXV. If anyone conceives, that an object of his love joins itself to another with closer bonds of friendship than he himself has attained to, he will be affected with hatred towards the loved object and with envy towards his rival.

- XXXVI. He who remembers a thing, in which he has once taken delight, desires to possess it under the same circumstances as when he first took delight therein.

- XXXVII. Desire arising through pain or pleasure, hatred or love, is greater in proportion as the emotion is greater.

- XXXVIII. If a man has begun to hate an object of his love, so that love is thoroughly destroyed, he will, causes being equal, regard it with more hatred than if he had never loved it, and his hatred will be in proportion to the strength of his former love.

- XXXIX. He who hates anyone will endeavour to do him an injury, unless he fears that a greater injury will thereby accrue to himself; on the other hand, he who loves anyone will, by the same law, seek to benefit him.

- XL. He, who conceives himself to be hated by another, and believes that he has given him no cause for hatred, will hate that other in return.

- XLI. If anyone conceives that he is loved by another, and believes that he has given no cause for such love, he will love that other in return.

- XLII. He who has conferred a benefit on anyone from motives of love or honour will feel vain, if he sees that the benefit is received without gratitude.

- XLIII. Hatred is increased by being reciprocated, and can on the other hand be destroyed by love.

- XLIV. Hatred which is completely vanquished by love passes into love: and love is thereupon greater than if hatred had not preceded it.

- XLV. If a man conceives, that anyone similar to himself hates anything also similar to himself which he loves, he will hate that person.

- XLVI. If a man has been affected pleasurably or painfully by anyone, of a class or nation different from his own, and if the pleasure or pain has been accompanied by the idea of the said stranger as cause, under the general category of the class or nation: the man will feel love or hatred, not only to the individual stranger, but also to the whole class or nation whereto he belongs.

- XLVII. Joy arising from the fact, that anything we hate is destroyed, or suffers other injury, is never unaccompanied by a certain pain in us.

- XLVIII. Love or hatred towards, for instance, Peter is destroyed, if the pleasure involved in the former, or the pain involved in the latter emotion, be associated with the idea of another cause: and will be diminished in proportion as we conceive Peter not to have been the sole cause of either emotion.

- XLIX. Love or hatred towards a thing, which we conceive to be free, must, other conditions being similar, be greater than if it were felt towards a thing acting by necessity.

- L. Anything whatever can be, accidentally, a cause of hope or fear.

- LI. Different men may be differently affected by the same object, and the same man may be differently affected at different times by the same object.

- LII. An object which we have formerly seen in conjunction with others, and which we do not conceive to have any property that is not common to many, will not be regarded by us for so long, as an object which we conceive to have some property peculiar to itself.

- LIII. When the mind regards itself and its own power of activity, it feels pleasure: and that pleasure is greater in proportion to the distinctness wherewith it conceives itself and its own power of activity.

- LIV. The mind endeavours to conceive only such things as assert its power of activity.

- LV. When the mind contemplates its own weakness, it feels pain thereat.

- LVI. There are as many kinds of pleasure, of pain, of desire, and of every emotion compounded of these, such as vacillations of spirit, or derived from these, such as love, hatred, hope, fear, &c., as there are kinds of objects whereby we are affected.

- LVII. Any emotion of a given individual differs from the emotion of another individual, only in so far as the essence of the one individual differs from the essence of the other.

- LVIII. Besides pleasure and desire, which are passivities or passions, there are other emotions derived from pleasure and desire, which are attributable to us in so far as we are active.

- LIX. Among all the emotions attributable to the mind as active, there are none which cannot be referred to pleasure or pain.[54]

Hierarchy of knowledge

Spinoza has a three-stage hierarachy of knowledge:

- Confused sense impressions without ordering by the intellect. It's knowledge from random experience. We don't understand what's happening, like walking on a city street and hearing a horn blast somewhere; we don't know what it means.

- Knowledge from common notions and adequate ideas of the properties of things; knowing that a thing happens by necessity, but not how it happens. We know when we're thirsty, we should drink; but we can't specify how the water is used in our body's metabolism, for example.

- Best knowledge; logically true, adequate ideas; ideas of things in their proper causal contexts. This is scientific knowledge. It's clear understanding. It's like knowing that the two other angles in a right triangle add up to 90 degrees, and knowing why this happens. Overall, however, since Spinoza did not elaborate much about the three categories of knowledge, there is debate among scholars about what Spinoza meant precisely by these three categories.

Freedom of the will

Can a person freely choose chocolate mousse or vanilla cream pie? People are aware of ideas in their heads as well as their drives and hungers, and with this awareness, people think that they freely choose to do things. A person can feel hungry for chocolate mousse and not be aware of how exposure to an advertisement in a magazine the other day helped incite this craving; and there are many other factors which have caused this craving.

But this sense of freedom is false, according to Spinoza, since in a world in which everything is determined, in which billiard balls are bouncing against other billiard balls, and in which ideas of billiard balls are bouncing against the ideas of other billiard balls, then particular choices such as chocolate mousse are fated in advance. There are many factors steering our choices which we're usually not aware of. It's impossible to choose vanilla cream pie. We choose chocolate mousse by an act of independent uncaused will. It's the only possibility, since everything we do is determined by Nature, by other finite modes, according to Spinoza. Spinoza thought that we confuse our volition for free will and that we fail to understand the myriads of forces which caused us to want to choose the mousse. For example, a baby thinks that it freely desires to drink milk. Spinoza doesn't think there is some part of humans called the free will. Desires, wants, volitions–these are all ideas in our heads which are themselves determined logically by other ideas.

The Passions

Humans are emotional beings, in Spinoza's view, and the emotions are bonds of enslavement. Spinoza wrote:

| “ | Human infirmity in moderating and checking the emotions I name bondage: for, when a man is a prey to his emotions, he is not his own master, but lies at the mercy of fortune: so much so, that he is often compelled, while seeing that which is better for him, to follow that which is worse.[55] | ” |

For example, a person may know intellectually that smoking causes cancer, yet be unable to quit smoking. An overweight person may know intellectually their body doesn't need a second chocolate mousse, but he or she eats it anyway. Emotions are powerful forces. Merely knowing what's right isn't enough to overpower them.

So, how can a person triumph over powerful emotions? To answer this, Spinoza first explored issues such as "goodness" and "perfection."

People judge whether something is perfect based on guesses about their supposed purpose; how well does it fit a specific purpose? A house is perfect if it keeps out rain. But Spinoza insists nature does not act with any end in view and therefore there are no purposes. So, it's hard for humans to judge a thunderstorm as perfect or imperfect because people have no sense about the purpose of this rainstorm.

Accordingly, words like good and bad don't describe a quality inside a thing. There's no such thing as a good chair, for example, but a chair is good only to the extent that it fits our purpose for sitting. Spinoza wrote: music is good for him that is melancholy, bad for him that mourns; for him that is deaf, it is neither good nor bad."[56] Good is what's useful to us; evil is what hinders us.[56] Good things allow us to affect other things, or be affected by other things, in ways which help us. Should we move to a smaller city like Scranton or a larger city like New York? Spinoza would choose New York, if all other aspects of the choice were equal, because a larger city permits more chances for us to affect things and be affected by things, such as career possibilities, job choices, people, music, magazines, and so forth.

Spinoza saw emotions as being powerful; reason, in contrast, has limited power. A false idea is not removed merely by the presence of a true one.[57] For example, Spinoza wrote that the sun appears as if it's about two hundred feet away, and even though we know that its millions of miles away, it still appears to us to be two hundred feet away.[57] But we can still overcome mistaken ideas but it requires higher order thinking processes.

Bondage and freedom and blessedness

We can have conflicting emotions in which we're drawn in different directions. Spinoza offered a new list of propositions dealing with emotions and bondage and freedom and blessedness.

- I. No positive quality possessed by a false idea is removed by the presence of what is true, in virtue of its being true.

- II. We are only passive, in so far as we are part of Nature, which cannot be conceived by itself without other parts.

- III. The force whereby a man persists in existing is limited, and is infinitely surpassed by the power of external causes.

- IV. It is impossible, that man should not be apart of Nature, or that he should be capable of undergoing no changes, save such as can be understood through his nature only as their adequate cause.

- V. The power and increase of every passion, and its persistence in existing are not defined by the power, whereby we ourselves endeavour to persist in existing, but by the power of an external cause compared with our own.

- VI. The force of any passion or emotion can overcome the rest of a man's activities or power, so that the emotion becomes obstinately fixed to him.

- VII. An emotion can only be controlled or destroyed by another emotion contrary thereto, and with more power for controlling emotion.

- VIII. The knowledge of good and evil is nothing else but the emotions of pleasure or pain, in so far as we are conscious thereof.

- IX. An emotion, whereof we conceive the cause to be with us at the present time, is stronger than if we did not conceive the cause to be with us.

- X. Towards something future, which we conceive as close at hand, we are affected more intensely, than if we conceive that its time for existence is separated from the present by a longer interval; so too by the remembrance of what we conceive to have not long passed away we are affected more intensely, than if we conceive that it has long passed away.

- XI. An emotion towards that which we conceive as necessary is, when other conditions are equal, more intense, than an emotion towards that which impossible, or contingent, or non-necessary.

- XII. An emotion towards a thing, which we know not to exist at the present time, and which we conceive as possible, is more intense, other conditions being equal, than an emotion towards a thing contingent.

- XIII. Emotion towards a thing contingent, which we know not to exist in the present, is, other conditions being equal, fainter than an emotion towards a thing past.

- XIV. A true knowledge of good and evil cannot check any emotion by virtue of being true, but only in so far as it is considered as an emotion.

- XV. Desire arising from the knowledge of good and bad can be quenched or checked by many of the other desires arising from the emotions whereby we are assailed.

- XVI. Desire arising from the knowledge of good and evil, in so far as such knowledge regards what is future, may be more easily controlled or quenched, than the desire for what is agreeable at the present moment.

- XVII. Desire arising from the true knowledge of good and evil, in so far as such knowledge is concerned with what is contingent, can be controlled far more easily still, than desire for things that are present.

- XVIII. Desire arising from pleasure is, other conditions being equal, stronger than desire arising from pain.

- XIX. Every man, by the laws of his nature, necessarily desires or shrinks from that which he deems to be good or bad.

- XX. The more every man endeavours, and is able to seek what is useful to him--in other words, to preserve his own being--the more is he endowed with virtue; on the contrary, in proportion as a man neglects to seek what is useful to him, that is, to preserve his own being, he is wanting in power.

- XXI. No one can desire to be blessed, to act rightly, and to live rightly, without at the same time wishing to be, to act, and to live--in other words, to actually exist.

- XXII. No virtue can be conceived as prior to this endeavour to preserve one's own being.

- XXIII. Man, in so far as he is determined to a particular action because he has inadequate ideas, cannot be absolutely said to act in obedience to virtue; he can only be so described, in so far as he is determined for the action because he understands.

- XXIV. To act absolutely in obedience to virtue is in us the same thing as to act, to live, or to preserve one's being (these three terms are identical in meaning) in accordance with the dictates of reason on the basis of seeking what is useful to one's self.

- XXV. No one wishes to preserve his being for the sake of anything else.

- XXVI. Whatsoever we endeavour in obedience to reason is nothing further than to understand; neither does the mind, in so far as it makes use of reason, judge anything to be useful to it, save such things as are conducive to understanding.

- XXVII. We know nothing to be certainly good or evil, save such things as really conduce to understanding, or such as are able to hinder us from understanding.

- XXVIII. The mind's highest good is the knowledge of God, and the mind's highest virtue is to know God.

- XXIX. No individual thing, which is entirely different from our own nature, can help or check our power of activity, and absolutely nothing can do us good or harm, unless it has something in common with our nature.

- XXX. A thing cannot be bad for us through the quality which it has in common with our nature, but it is bad for us in so far as it is contrary to our nature.

- XXXI. In so far as a thing is in harmony with our nature, it is necessarily good.

- XXXII. In so far as men are a prey to passion, they cannot, in that respect, be said to be naturally in harmony.

- XXXIII. Men can differ in nature, in so far as they are assailed by those emotions, which are passions, or passive states; and to this extent one and the same man is variable and inconstant.

- XXXIV. In so far as men are assailed by emotions which are passions, they can be contrary one to another.

- XXXV. In so far only as men live in obedience to reason, do they always necessarily agree in nature.

- XXXVI. The highest good of those who follow virtue is common to all, and therefore all can equally rejoice therein.

- XXXVII. The good which every man, who follows after virtue, desires for himself he will also desire for other men, and so much the more, in proportion as he has a greater knowledge of God.

- XXXVIII. Whatsoever disposes the human body, so as to render it capable of being affected in an increased number of ways, or of affecting external bodies in an increased number of ways, is useful to man; and is so, in proportion as the body is thereby rendered more capable of being affected or affecting other bodies in an increased number of ways; contrariwise, whatsoever renders the body less capable in this respect is hurtful to man.

- XXXIX. Whatsoever brings about the preservation of the proportion of motion and rest, which the parts of the human body mutually possess, is good; contrariwise, whatsoever causes a change in such proportion is bad.

- XL. Whatsoever conduces to man's social life, or causes men to live together in harmony, is useful, whereas whatsoever brings discord into a State is bad.

- XLI. Pleasure in itself is not bad but good: contrariwise, pain in itself is bad.

- XLII. Mirth cannot be excessive, but is always good; contrariwise, Melancholy is always bad.

- XLIII. Stimulation may be excessive and bad; on the other hand, grief may be good, in so far as stimulation or pleasure is bad.

- XLIV. Love and desire may be excessive.

- XLV. Hatred can never be good.

- XLVI. He, who lives under the guidance of reason, endeavours, as far as possible, to render back love, or kindness, for other men's hatred, anger, contempt, &c., towards him.

- XLVII. Emotions of hope and fear cannot be in themselves good.

- XLVIII. The emotions of over-esteem and disparagement are always bad.

- XLIX. Over-esteem is apt to render its object proud.

- L. Pity, in a man who lives under the guidance of reason, is in itself bad and useless.

- LI. Approval is not repugnant to reason, but can agree therewith and arise therefrom.

- LII. Self-approval may arise from reason, and that which arises from reason is the highest possible.

- LIII. Humility is not a virtue, or does not arise from reason.

- LIV. Repentance is not a virtue, or does not arise from reason; but he who repents of an action is doubly wretched or infirm.

- LV. Extreme pride or dejection indicates extreme ignorance of self.

- LVI. Extreme pride or dejection indicates extreme infirmity of spirit.

- LVII. The proud man delights in the company of flatterers and parasites, but hates the company of the high-minded.

- LVIII. Honour (gloria) is not repugnant to reason, but may arise therefrom.

- LIX. To all the actions, whereto we are determined by emotion wherein the mind is passive, we can be determined without emotion by reason.

- LX. Desire arising from a pleasure or pain, that is not attributable to the whole body, but only to one or certain parts thereof, is without utility in respect to a man as a whole.

- LXI. Desire which springs from reason cannot be excessive.

- LXII. In so far as the mind conceives a thing under the dictates of reason, it is a affected equally, whether the idea be of a thing future, past, or present.

- LXIII. He who is led by fear, and does good in order to escape evil, is not led by reason.

- LXIV. The knowledge of evil is an inadequate knowledge.

- LXV. Under the guidance of reason we should pursue the greater of two goods and the lesser of two evils.

- LXVI. We may, under the guidance of reason, seek a greater good in the future in preference to a lesser good in the present, and we may seek- a lesser evil in the present in preference to a greater evil in the future.

- LXVII. A free man thinks of death least of all things; and his wisdom is a meditation not of death but of life.

- LXVIII. If men were born free, they would, so long as they remained free, form no conception of good and evil.

- LXIX. The virtue of a free man is seen to be as great, when it declines dangers, as when it overcomes them.

- LXX. The free man, who lives among the ignorant, strives, as far as he can, to avoid receiving favours from them.

- LXXI. Only free men are thoroughly grateful one to another.

- LXXII. The free man never acts fraudently, but always in good faith.

- LXXIII. The man, who is guided by reason, is more free in a State, where he lives under a general system of law, than in solitude, where he is independent.[57]

Spinoza thought that all living beings strived to keep living. He wrote: "Each thing, as far as it can by its own power, strives to persevere in its being."

When things affect us and we respond with adequate active understanding, there will be improvement in our condition. But when things affect us and we respond passively, then what happens to us is beyond our control. Our situation could improve and we'd feel joy, or deteriorate and we'd feel sad, but we don't control what happens to us in these instances. Spinoza thought most of mankind, in most situations, dealt with the world passively, not actively.

The emotions of hope and fear make us slaves to things outside us, that is, they link our happiness to things we can't control. We hope tomorrow will be sunny and we fear a possible thunderstorm, but our happiness, as a result, depends on weather conditions and not on our own mental activity. Spinoza sees humans as "thoroughly egoistic agents trying as best we can to pursue things we think will help us, which we hope will bring us joy or further our self-preservation.

Virtue and freedom

Since there is no good and evil in an absolute sense,[2] but things can be good for us if, by actively understanding them in an adequate sense, we know that they can take us to a higher level. As humans, we're in the world of nature and will always be affected by things in nature. Life is a struggle between competing affects, and this struggle takes place in our minds as well. And truth, by itself, doesn't trump a powerful emotion, but it's a competition among competing desires. This explains why people can know very well "what's best" but not do it; a smoker hooking on nicotine may know intellectually that the smoking is harmful, but keep smoking, because the emotion is stronger than the logic. Reason is poorly suited to take on powerful forces like emotions; Sigmund Freud would have agreed.

The key to betterment is virtue which in the sense of acting in accordance with nature. It's successfully staying alive. It's striving, thriving, and prospering. And the key to having virtue, according to Spinoza, is "living according to the guidance of reason." He or she acts. Reason has universal imperatives that transcend personal differences akin to Kant's categorical imperatives. We need things in the world; reason shows us how to get them and live well in the world. Spinoza's model is not a Judeo-Christian one of ascetism with a monk living a solitary existence in a monastery; rather, it's seeking one's own advantage and enjoying life. The virtuous person judges what's good and what's evil and because these judgments are reason–guided, they're right. It's choosing things that don't just help a part of one's body but which helps the whole body. One isn't led astray by immediate gratification or the pursuit of transitory or partial goods.

What the virtuous person requires most of all is knowledge and understanding of cause and effect relationships regarding adequate ideas in the correct sequences. And the highest and best knowledge, according to Spinoza, is the knowledge of God or Nature. Spinoza wrote:

| “ | Knowledge of God is the mind's greatest good; its greatest virtue is to know God. | ” |

Know science. Study nature. Learn as much as possible. The virtuous person is therefore a free being. He or she is in control of oneself, as much as possible. It's the life of reason. Passions are held in check. People don't become obsessive about other people or things. We're relatively free from absurd emotions such as ambition or lust or greed or hate. We don't get over-elated in good news or overly sad with bad news. We have a more even-keep temperament.

A free person with knowledge of the duration of things would be able to make better decisions about future choices compared to present choices. Such a person is better poised to weigh the trade-off between a lesser present good versus a greater future one. A free student would choose the present sacrifice of homework for the much greater future benefit of success and understanding. The free person doesn't worry excessively about death but focuses on the joy of living. But this freedom isn't the freedom of the will since a person is still dependent on all of the myriad events happening in nature, but rather, the human can get a greater share of the determining within the fully determined universe of God or Nature. Spinoza argued that the totally free person is an impossibility for real humans, but it can be thought of as a model which we should try to emulate.

Self-betterment

How can we improve ourselves? Spinoza argues that it's important to understand what motivates us. People should try to see how too much attachment to an object that varies will mean that our own happiness varies when the object varies. Spinoza might advise: Don't focus obsessively on a lover or a bar of chocolate; rather, try to see the lover or chocolate as finite things. Try to separate the particular object from the way it affects us. Spinoza wrote:

| “ | if we separate emotions, or affects, from the thought of an external cause, and join them to other thoughts, then the love, or hate, toward the external cause is destroyed, as are the vacillations of mind arising from these affects. | ” |

Spinoza urges people to see the bigger picture of many causes and relationships, and don't focus obsessively on any single external cause. As a result, the intense love of one particular thing is spread out in a weaker intensity over many things. If we can get a "clear and distinct idea" of any particular passion, then its hold over us lessens. While we can't fight a strong emotion with reason or logic, we can fight a strong emotion with other emotions. Take the initiative and strive for a fuller knowledge of ourselves, Spinoza might have advised. Then, ideas in one's head become connected in a causal manner instead of random ideas haphazardly flung together.

Knowing that things happen by necessity helps us become emotionally more detached from their pull. Knowing something couldn't have happened otherwise means there's less cause for tears, for joy, for unhelpful emotional responses. It's nobody's fault. We don't get riled up. There's less of an urge to wag fingers or assign blame when there's spilt milk. Seeing passed events as necessary helps people deal with change positively with equanimity and calmness. People can focus on what's within, on stuff we can control, and realize we'll always be affected by emotions and passions, but people should try as best we can to moderate them.

And the highest expression and best way to restrain the passions, in Spinoza's view, is to love God. This means accepting that there's no ultimate good and evil, understanding the world, exploring causes and effects, and accepting fate and necessity. It is the highest love of all, argues Spinoza.

Ethics

A virtuous free person, in Spinoza's view, won't adopt an ethos of total self-interest but will be guided by reason to act kindly towards others.[2] People who have things in common with us can help us, and we can help them, and it's possible for people to work together in harmony. Of course, what prevents harmonious action is the passions, but by living in accord with reason, people value the same things and pursue the same goals. Virtuous persons pursue goals that are good for everyone because they're willing to share knowledge. And a virtuous person will strive to make other persons virtuous and free and good. This thinking mirrored Spinoza's own life; he had a circle of friends called the Collegiants.[3] He lived what he wrote.[58][59][60]

Society and the State

Spinoza agreed with Hobbes about the need for a sovereign power and that it was reasonable for persons motivated by self-interest to give up some rights for greater security as long as others made a similar agreement, in Spinoza's view. There wouldn't be a need for a state if people were all virtuous; but this isn't the case, unfortunately. But it's still a good idea for people to band together in associations to form a state. But it's necessary for government to use threats to maintain order and to prevent instances of broken contracts and violence as a result of the passions. The ideal state was a democracy which, in his view, was better able to help people pursue virtue and the life of reason. Spinoza's political thinking was published anonymously during his lifetime in a book called the Tractatus Theologico-Politicus.[3]

Criticism of Spinoza's philosophy

Some critics charge that Spinoza's idea that "every living being strives to keep itself alive" doesn't explain the possibility of suicide or the decay from ageing. There is disagreement about whether Spinoza was a pantheist or panentheist or an atheist. There are questions about what Spinoza thought about the idea of consciousness and whether the human mind could survive the death of the human body; philosophers debate these issues today.[5] There is speculation about what exactly is the difference between God and Nature or are they exactly the same thing? One writer pondered: "Natura Naturans is the most God-like side of God, eternal, unchanging, and invisible, while Natura Naturata is the most Nature-like side of God, transient, changing, and visible."[2] But a general difficulty is that the entire system is built from a few specific premises, and if these premises happen to be flawed, or, as Spinoza might say, inadequate, then the whole system can fall apart. Physicists question the idea of cause-and-effect by pointing to the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle as proof that the cause and effect principle doesn't apply at the subatomic level. According to this principle, it is impossible to predict where an electron will be at a given future time, since any attempt at measurement will distort the trajectory of an electron. However, some scientists agree that even if cause-and-effect may not apply at the subatomic level, they assert that causation does apply at the atomic level, and therefore Spinoza's logic still holds. Still another view is that cause-and-effect does apply at the subatomic level regardless of problems with prediction. These debates continue today.

See also

References

- ↑ Lisa Montanarelli (book reviewer). Spinoza stymies 'God's attorney' -- Stewart argues the secular world was at stake in Leibniz face off, San Francisco Chronicle, January 8, 2006. Retrieved on 2009-09-08.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Kelley L. Ross (1999). Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677). History of Philosophy As I See It. Retrieved on 2009-12-07. “While for Spinoza all is God and all is Nature, the active/passive dualism enables us to restore, if we wish, something more like the traditional terms. Natura Naturans is the most God-like side of God, eternal, unchanging, and invisible, while Natura Naturata is the most Nature-like side of God, transient, changing, and visible.”

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Anthony Gottlieb. God Exists, Philosophically, 'The New York Times: Books', July 18, 1999. Retrieved on 2009-12-07. “Spinoza, a Dutch Jewish thinker of the 17th century, not only preached a philosophy of tolerance and benevolence but actually succeeded in living it. He was reviled in his own day and long afterward for his supposed atheism, yet even his enemies were forced to admit that he lived a saintly life.”

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 ANTHONY GOTTLIEB. God Exists, Philosophically (review of "Spinoza: A Life" by Steven Nadler), The New York Times -- Books, 2009-09-07. Retrieved on 2009-09-07.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Michael LeBuffe (book reviewer). Spinoza's Ethics: An Introduction, by Steven Nadler, 'University of Notre Dame', 2006-11-05. Retrieved on 2009-12-07. “Spinoza's Ethics is a recent addition to Cambridge's Introductions to Key Philosophical Texts, a series developed for the purpose of helping readers with no specific background knowledge to begin the study of important works of Western philosophy...”

- ↑ EINSTEIN BELIEVES IN "SPINOZA'S GOD"; Scientist Defines His Faith in Reply, to Cablegram From Rabbi Here. SEES A DIVINE ORDER But Says Its Ruler Is Not Concerned "Wit Fates and Actions of Human Beings.", 'The New York Times', April 25, 1929. Retrieved on 2009-09-08.

- ↑ Spinoza, "God-Intoxicated Man"; Three Books Which Mark the Three Hundredth Anniversary of the Philosopher's Birth BLESSED SPINOZA. A Biography. By Lewis Browne. 319 pp. New York: The Macmillan Com- pany. $4. SPINOZA. Liberator of God and Man. By Benjamin De Casseres, 145pp. New York: E.Wickham Sweetland. $2. SPINOZA THE BIOSOPHER. By Frederick Kettner. Introduc- tion by Nicholas Roerich, New Era Library. 255 pp. New York: Roerich Museum Press. $2.50. Spinoza, 'The New York Times', November 20, 1932. Retrieved on 2009-09-08.

- ↑ Spinoza's First Biography Is Recovered; THE OLDEST BIOGRAPHY OF SPINOZA. Edited with Translations, Introduction, Annotations, &c., by A. Wolf. 196 pp. New York: Lincoln Macveagh. The Dial Press., 'The New York Times', December 11, 1927. Retrieved on 2009-09-08.

- ↑ IRWIN EDMAN. The Unique and Powerful Vision of Baruch Spinoza; Professor Wolfson's Long-Awaited Book Is a Work of Illuminating Scholarship. (Book review) THE PHILOSOPHY OF SPINOZA. By Henry Austryn Wolfson, 'The New York Times', July 22, 1934. Retrieved on 2009-09-08.

- ↑ ROTH EVALUATES SPINOZA, 'Los Angeles Times', Sep 8, 1929. Retrieved on 2009-09-08.

- ↑ SOCIAL NEWS BOOKS. TRIBUTE TO SPINOZA PAID BY EDUCATORS; Dr. Robinson Extols Character of Philosopher, 'True to the Eternal Light Within Him.' HAILED AS 'GREAT REBEL'; De Casseres Stresses Individualism of Man Whose Tercentenary Is Celebrated at Meeting., 'The New York Times', November 25, 1932. Retrieved on 2009-09-08.

- ↑ Harold Bloom (book reviewer). Deciphering Spinoza, the Great Original -- Book review of "Betraying Spinoza. The Renegade Jew Who Gave Us Modernity." By Rebecca Goldstein, The New York Times, June 16, 2006. Retrieved on 2009-09-08.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Translated by R. H. M. Elwes. Etext of The Ethics, by Benedict de Spinoza, 'The Project Gutenberg', 1883. Retrieved on 2009-12-10. “By substance I mean that which is in itself, and is conceived through itself: in other words, that of which a conception can be formed independently of any other conception.”

- ↑ R. H. M. Elwes (translator). Etext of The Ethics, by Benedict de Spinoza, 'The Project Gutenberg', 1883. Retrieved on 2009-12-10. “From a given definite cause an effect necessarily follows; and, on the other hand, if no definite cause be granted, it is impossible that an effect can follow.”

- ↑ R. H. M. Elwes (translator). Etext of The Ethics, by Benedict de Spinoza, 'The Project Gutenberg', 1883. Retrieved on 2009-12-10. “There cannot exist in the universe two or more substances having the same nature or attribute.”

- ↑ R. H. M. Elwes (translator). Etext of The Ethics, by Benedict de Spinoza, 'The Project Gutenberg', 1883. Retrieved on 2009-12-10. “A thing is called 'finite after its kind' when it can be limited by another thing of the same nature; for instance, a body is called finite because we always conceive another greater body. So, also, a thought is limited by another thought, but a body is not limited by thought, nor a thought by body.”

- ↑ R. H. M. Elwes (translator). Etext of The Ethics, by Benedict de Spinoza, 'The Project Gutenberg', 1883. Retrieved on 2009-12-10. “Things which have nothing in common cannot be one the cause of the other.”

- ↑ R. H. M. Elwes (translator). Etext of The Ethics, by Benedict de Spinoza, 'The Project Gutenberg', 1883. Retrieved on 2009-12-10. “There cannot exist in the universe two or more substances having the same nature or attribute.”

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 R. H. M. Elwes (translator). Etext of The Ethics, by Benedict de Spinoza, 'The Project Gutenberg', 1883. Retrieved on 2009-12-10. “Every substance is necessarily infinite.”

- ↑ R. H. M. Elwes (translator). Etext of The Ethics, by Benedict de Spinoza, 'The Project Gutenberg', 1883. Retrieved on 2009-12-10. “God, and all the attributes of God, are eternal. Proof--God (by Def. vi.) is substance, which (by Prop. xi.) necessarily exists, that is (by Prop. vii.) existence appertains to its nature, or (what is the same thing) follows from its definition; therefore, God is eternal (by Def. vii.).”