Archive:New Draft of the Week: Difference between revisions

imported>Meg Taylor mNo edit summary |

imported>Daniel Mietchen (updated) |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

'''To add a new nominee or vote for an existing nominee, click ''edit'' for this section and follow the instructions''' | '''To add a new nominee or vote for an existing nominee, click ''edit'' for this section and follow the instructions''' | ||

Ellesmere Chaucer manuscript | |||

Ellipse | |||

<!-- | <!-- | ||

* Copy the first entry in the table just below (to be used as a form to add your nominee. | * Copy the first entry in the table just below (to be used as a form to add your nominee. | ||

| Line 21: | Line 22: | ||

! Nominated article !! Vote<br/>Score !! Supporters !! Specialist supporters !! Date created | ! Nominated article !! Vote<br/>Score !! Supporters !! Specialist supporters !! Date created | ||

|- | |- | ||

| <!-- article --> [[Aeneid]] | | <!-- article --> [[Aeneid]] | ||

| Line 34: | Line 29: | ||

| <!-- date created --> 28 March 2010 | | <!-- date created --> 28 March 2010 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| <!-- article --> | | <!-- article --> [[Ellipse]] | ||

| <!-- score --> | | <!-- score --> 1 | ||

| <!-- supporters --> | | <!-- supporters --> [[User:Daniel Mietchen|Daniel Mietchen]] 13:12, 1 May 2010 (UTC) | ||

| <!-- specialist supporters --> | |||

| <!-- date created --> April 28, 2010 | |||

|- | |||

| <!-- article --> [[Ellesmere Chaucer manuscript]] | |||

| <!-- score --> 1 | |||

| <!-- supporters --> [[User:Daniel Mietchen|Daniel Mietchen]] 13:12, 1 May 2010 (UTC) | |||

| <!-- specialist supporters --> | | <!-- specialist supporters --> | ||

| <!-- date created --> | | <!-- date created --> April 22, 2010 | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 52: | Line 53: | ||

== View Current Transcluded Nominees (after they have been transcluded by an Administrator) == | == View Current Transcluded Nominees (after they have been transcluded by an Administrator) == | ||

The next New Draft of the Week will be the article with the most votes at 1 AM UTC on Thursday, | The next New Draft of the Week will be the article with the most votes at 1 AM UTC on Thursday, 13 May, 2010. | ||

| Line 63: | Line 64: | ||

{{Featured Article Candidate | {{Featured Article Candidate | ||

| article = | | article = Tall tale | ||

| supporters = [[User:Daniel Mietchen|Daniel Mietchen]]<br/> | | supporters = [[User:Daniel Mietchen|Daniel Mietchen]];<br/> [[User: Howard C. Berkowitz|Howard C. Berkowitz]];<br/>[[User:Paul Wormer|Paul Wormer]];<br/> | ||

| specialists = | | specialists = | ||

| created = | | created = 2010-03-09 | ||

| score = | | score = 3 | ||

}} | }} | ||

| Line 79: | Line 80: | ||

Do not edit anything else -- the following line changes the Welcome page automatically. | Do not edit anything else -- the following line changes the Welcome page automatically. | ||

--> | --> | ||

<onlyinclude>{{Featured Article| | <onlyinclude>{{Featured Article|Tall tale}}</onlyinclude> | ||

<!-- | <!-- | ||

Move previous winner articles to the next section | Move previous winner articles to the next section | ||

| Line 88: | Line 89: | ||

<div style="height:25em; overflow:auto; background:#f9f9f9; border:1px solid #aaa;"> | <div style="height:25em; overflow:auto; background:#f9f9f9; border:1px solid #aaa;"> | ||

{{rpr|Plane (geometry)}} | |||

{{rpr|Steam}} | {{rpr|Steam}} | ||

{{rpr|Wasan}} | {{rpr|Wasan}} | ||

Revision as of 08:12, 1 May 2010

The New Draft of the Week is a chance to highlight a recently created Citizendium article that has just started down the road of becoming a Citizendium masterpiece.

It is chosen each week by vote in a manner similar to that of its sister project, the Article of the Week.

Add New Nominees Here

To add a new nominee or vote for an existing nominee, click edit for this section and follow the instructions Ellesmere Chaucer manuscript Ellipse

| Nominated article | Vote Score |

Supporters | Specialist supporters | Date created |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aeneid | 2 | Daniel Mietchen 23:38, 10 April 2010 (UTC); Meg Ireland |

28 March 2010 | |

| Ellipse | 1 | Daniel Mietchen 13:12, 1 May 2010 (UTC) | April 28, 2010 | |

| Ellesmere Chaucer manuscript | 1 | Daniel Mietchen 13:12, 1 May 2010 (UTC) | April 22, 2010 |

If you want to see how these nominees will look on the CZ home page (if selected as a winner), scroll down a little bit.

Transclusion of the above nominees (to be done by an Administrator)

- Transclude each of the nominees in the above "Table of Nominee" as per the instructions at Template:Featured Article Candidate.

- Then add the transcluded article to the list in the next section below, using the {{Featured Article Candidate}} template.

View Current Transcluded Nominees (after they have been transcluded by an Administrator)

The next New Draft of the Week will be the article with the most votes at 1 AM UTC on Thursday, 13 May, 2010.

| Nominated article | Supporters | Specialist supporters | Dates | Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

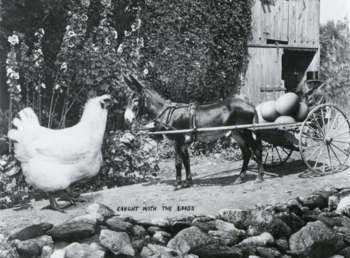

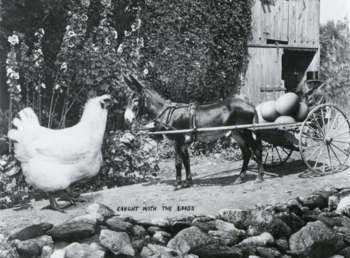

(CC) Image: Wisconsin Historical Society A tall-tale postcard based on a photomontage, illustrating the kind of exaggeration typical for tall tales: A dwarf drives a cart, drawn by a mule, filled with giant eggs. The dwarf is wearing a suit and a top hat. The mule is being confronted on the road by a giant chicken. A tall tale is a narrative, song or jest that depicts exaggerated situations, incredible boasts or impossible achievements. In a narrow sense, the term applies to stories told by American frontiersmen, and indeed the term itself originates from the mid-1800s.[1] In a wider sense, however, a tall tale is a specimen of mendacious literature, often a folk narrative, whether or not recorded in writing. Written forms, however, also exist as literary creations in their own right. As such, the genre is considered to be universal and of all ages.[2] Tall tales are not just fictitious, they are patently impossible. If the tall tale is a first-person narrative, the narrator pretends to believe his own story,[3] while in third-person narratives, the account is likewise presented as true. It is a characteristic of the tall tale that it is told by a liar, not by a fallible narrator. While delimitations are difficult to draw sharply, tall tales should therefore be distinguished from fables (which characteristically present a moral) and from science fiction or science fantasy (which by its very nature presents itself as a fantasy). The American traditionTall tales in the American folk tale tradition often snowball round such well-known figures as Bill Cody and Davy Crockett. But there is also a New England tradition, including the tale of Captain Stormalong, who, caught in a storm, steered his ship through the Panama Isthmus, thus digging the canal. Apart from the oral tradition, there are literary specimens by Washington Irving (History of New York, 1809) and Mark Twain (Life on the Mississippi, 1883).[4] A discontinuous history: mendacious literatureNon-Western traditionsBecause lies are of all ages, mendacious literature, whether oral or written, has had a long tradition and seems to occur all over the world. Certain themes recur internationally. Mendacious stories in other cultures include those in the One thousand and One Nights, while they are also found in the Talmud.[5] The Western traditionIn Western Europe, the precursor is Lucian of Samosata, who lived in the second century, and whose account of his sea voyage is packed with marvels. Of much later date is the eleventh-century Modus florum, where the lie is explicit: by telling mendacious stories, the protagonist is accepted as suitor to the king’s daughter.[6] Riddles, lies, and wishesMendacious songs from the Middle Ages have been handed down in song books. They occupy a position in between other fantastic genres, such as riddles and wish-fulfilment songs. Riddles may depict the impossible or the seemingly impossible. Thus, a bird without wings is a recurring motif, but in certain contexts, it is revealed to stand for something else: it may then be a metaphor for a snowflake. By contrast, an actual impossibility is postulated in a sixteenth-century German song, where a young man undertakes to marry a fair maid if she proves capable of weaving silk from straw.[7] The lie may be presented as a dream: in one of these songs, the narrator rides a three-legged ox around the world, but while he acknowledges that this is something he has dreamt, let the reader take note: the narrator will not tell lies! While the narrator pretends to believe his lie, it is not always easy to ascertain what the listener’s response was supposed to be. Was he to take seriously the tale about a mute man giving information, a naked person putting a millstone in his pocket? And was he really intended to believe the stories about Cockaigne, with its cakes hanging from trees, its animals defecating gold, its rejuvenating river? Such stories have been taken to make no claim to anything but entertainment, or alternatively, to satirize man’s greed. On the other hand, it has been assumed that these texts functioned in a context where nothing was deemed impossible: any wish, if cherished in earnest, was capable of fulfilment.[8] Riddle, lie and wish are closely related here. GermanAn early German example, Sō ist diz von Lügenen, dates from the fourteenth century, and once again, the lie is explicit: the title announces that this is a book about lies. Later stories deal with Schlaraffenland (a counterpart to Cockaigne), while a compilation of popular lore was published as Der edle Finkenritter (1559). H.W. Kirchhof’s Wendunmut (1563) relates fantastic adventures. Raspe’s Munchausen (1785) was long thought to be German, but its author had in fact fled to England and wrote his famous narrative in English.[9] FrenchThe French name for such false stories was contes-menteries, and a number of these were collected in Nouvelle fabrique des excellents traits de vérité (1579). Here, too, the title claims that the stories are true. A Swiss literary narrative by Rodolphe Töpffer is the Histoire de M. Cryptogame (1846).[10] Themes and motifsUnlike the deliberate lies recounted in more or less literary forms by Poggio, Raspe, Töpffer, Mark Twain and others, popular tradition is subject to decay, which makes it impossible to ascertain the provenance of many mendacious tales. There is, in addition, little doubt that early editions have been lost.[11] The origins and continuity of tales which have been handed down in extant collections are often impossible to trace. But certain motifs and themes recur.

References

|

Daniel Mietchen; Howard C. Berkowitz; Paul Wormer; |

3

|

Current Winner (to be selected and implemented by an Administrator)

To change, click edit and follow the instructions, or see documentation at {{Featured Article}}.

| The metadata subpage is missing. You can start it via filling in this form or by following the instructions that come up after clicking on the [show] link to the right. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

A tall-tale postcard based on a photomontage, illustrating the kind of exaggeration typical for tall tales: A dwarf drives a cart, drawn by a mule, filled with giant eggs. The dwarf is wearing a suit and a top hat. The mule is being confronted on the road by a giant chicken.

A tall tale is a narrative, song or jest that depicts exaggerated situations, incredible boasts or impossible achievements. In a narrow sense, the term applies to stories told by American frontiersmen, and indeed the term itself originates from the mid-1800s.[1] In a wider sense, however, a tall tale is a specimen of mendacious literature, often a folk narrative, whether or not recorded in writing. Written forms, however, also exist as literary creations in their own right. As such, the genre is considered to be universal and of all ages.[2]

Tall tales are not just fictitious, they are patently impossible. If the tall tale is a first-person narrative, the narrator pretends to believe his own story,[3] while in third-person narratives, the account is likewise presented as true. It is a characteristic of the tall tale that it is told by a liar, not by a fallible narrator. While delimitations are difficult to draw sharply, tall tales should therefore be distinguished from fables (which characteristically present a moral) and from science fiction or science fantasy (which by its very nature presents itself as a fantasy).

The American tradition

Tall tales in the American folk tale tradition often snowball round such well-known figures as Bill Cody and Davy Crockett. But there is also a New England tradition, including the tale of Captain Stormalong, who, caught in a storm, steered his ship through the Panama Isthmus, thus digging the canal. Apart from the oral tradition, there are literary specimens by Washington Irving (History of New York, 1809) and Mark Twain (Life on the Mississippi, 1883).[4]

A discontinuous history: mendacious literature

Non-Western traditions

Because lies are of all ages, mendacious literature, whether oral or written, has had a long tradition and seems to occur all over the world. Certain themes recur internationally. Mendacious stories in other cultures include those in the One thousand and One Nights, while they are also found in the Talmud.[5]

The Western tradition

In Western Europe, the precursor is Lucian of Samosata, who lived in the second century, and whose account of his sea voyage is packed with marvels. Of much later date is the eleventh-century Modus florum, where the lie is explicit: by telling mendacious stories, the protagonist is accepted as suitor to the king’s daughter.[6]

Riddles, lies, and wishes

Mendacious songs from the Middle Ages have been handed down in song books. They occupy a position in between other fantastic genres, such as riddles and wish-fulfilment songs. Riddles may depict the impossible or the seemingly impossible. Thus, a bird without wings is a recurring motif, but in certain contexts, it is revealed to stand for something else: it may then be a metaphor for a snowflake. By contrast, an actual impossibility is postulated in a sixteenth-century German song, where a young man undertakes to marry a fair maid if she proves capable of weaving silk from straw.[7]

The lie may be presented as a dream: in one of these songs, the narrator rides a three-legged ox around the world, but while he acknowledges that this is something he has dreamt, let the reader take note: the narrator will not tell lies!

While the narrator pretends to believe his lie, it is not always easy to ascertain what the listener’s response was supposed to be. Was he to take seriously the tale about a mute man giving information, a naked person putting a millstone in his pocket? And was he really intended to believe the stories about Cockaigne, with its cakes hanging from trees, its animals defecating gold, its rejuvenating river? Such stories have been taken to make no claim to anything but entertainment, or alternatively, to satirize man’s greed. On the other hand, it has been assumed that these texts functioned in a context where nothing was deemed impossible: any wish, if cherished in earnest, was capable of fulfilment.[8] Riddle, lie and wish are closely related here.

German

An early German example, Sō ist diz von Lügenen, dates from the fourteenth century, and once again, the lie is explicit: the title announces that this is a book about lies. Later stories deal with Schlaraffenland (a counterpart to Cockaigne), while a compilation of popular lore was published as Der edle Finkenritter (1559). H.W. Kirchhof’s Wendunmut (1563) relates fantastic adventures. Raspe’s Munchausen (1785) was long thought to be German, but its author had in fact fled to England and wrote his famous narrative in English.[9]

French

The French name for such false stories was contes-menteries, and a number of these were collected in Nouvelle fabrique des excellents traits de vérité (1579). Here, too, the title claims that the stories are true. A Swiss literary narrative by Rodolphe Töpffer is the Histoire de M. Cryptogame (1846).[10]

Themes and motifs

Unlike the deliberate lies recounted in more or less literary forms by Poggio, Raspe, Töpffer, Mark Twain and others, popular tradition is subject to decay, which makes it impossible to ascertain the provenance of many mendacious tales. There is, in addition, little doubt that early editions have been lost.[11] The origins and continuity of tales which have been handed down in extant collections are often impossible to trace. But certain motifs and themes recur.

- Cockaigne

The theme of the land bountiful is international. It may be called "Kurrelmurre" in German; "Luilekkerland" (“the land of easy and delight”) in Dutch; "Cuccagna", "Coquaingne" or Cockaygne" in Sicilian, French and English[12], but the theme remains the same. The story of this Paradise on earth, fulfilling all man’s wishes and thus depicting his greed, is utopia and satire at the same time.[13] Varieties occur; thus, the delicacies hanging from trees vary with the tastes of the audience, but delicacies they are, and in all cases they are freely available. There are Italian, French and English versions, and the story seems to have its roots in Antiquity.[14]

- The world inverted

Medieval carnival celebrations were characterized by an inversion of values. A commoner became a prince for a very short time, local authority lay low. The same motif of inversion is found in mendacious stories: a boor outwits Solomon[15], the quarry chases the hunter.

- Nobody

In Dutch and French stories, there occurs a non-existent hero or saint called “St Nobody” or “Seigneur Nemo” (“nemo” being Latin for “nobody”).

- The paradoxical handicap

The blind man seeing, the crippled person swimming or running, the nude man pocketing a stone, are all paradoxes which may be related to the tradition of riddles.[16]

- The tailless beast

A recurring motif is the tailless beast; a traveler rides a donkey suffering from this defect.[17]

References

- ↑ SOED s.v. “tall II".

- ↑ P.J. Meertens, “Leugenliteratuur”, in: A.G.H. Bachrach et al., Moderne Encyclopedie van de Wereldliteratuur , vol. 5. Haarlem/Antwerpen 1982:328-29

- ↑ Meertens 1982:328-29

- ↑ Merriam Webster’s Encyclopedia of Literature, Springfield 1995 s.v. “tall tale”

- ↑ Meertens 1982:328-29

- ↑ Meertens 1982:328-29

- ↑ G. Kalff, ‘’Het lied in de middeleeuwen’’, Ch. IV, “Raadsel-, Leugen en Wenschliederen”. Arnhem 1972[1884]:486-93, (online version [2] accessed Mar. 9, 2010)

- ↑ Kalff 1972[1884]:491, 493

- ↑ Meertens 1982:328-29

- ↑ Meertens 1982:328-29

- ↑ F.P. Wilson, “The English Jest-Books of the Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries”, in: Shakespearian and Other Studies, Oxford 1970[1969]:285-324

- ↑ Kalff 1972[1884]:489;

Meertens 1982:328-29;

P. de Keyser, “De nieuwe reis naar Luilekkerland”, in: P. de Keyser (ed.), Ars Folklorica Belgica. Noord- en Zuid-Nederlandse volkskunst. Antwerpen/Amsterdam, 1956:7-41 - ↑ De Keyser 1956:14

- ↑ Meertens 1982:328-29

- ↑ Wilson 1982:328-29

- ↑ Kalff 1972[1884]:488

- ↑ Meertens 1982:328-29

Previous Winners

Plane (geometry) [r]: In elementary geometry, a flat surface that entirely contains all straight lines passing through two of its points. [e]

Plane (geometry) [r]: In elementary geometry, a flat surface that entirely contains all straight lines passing through two of its points. [e] Steam [r]: The vapor (or gaseous) phase of water (H2O). [e]

Steam [r]: The vapor (or gaseous) phase of water (H2O). [e] Wasan [r]: Classical Japanese mathematics that flourished during the Edo Period from the 17th to mid-19th centuries. [e]

Wasan [r]: Classical Japanese mathematics that flourished during the Edo Period from the 17th to mid-19th centuries. [e] Racism in Australia [r]: The history of racism and restrictive immigration policies in the Commonwealth of Australia. [e]

Racism in Australia [r]: The history of racism and restrictive immigration policies in the Commonwealth of Australia. [e]- Think tank [r]: Add brief definition or description

Les Paul [r]: (9 June 1915 – 13 August 2009) American innovator, inventor, musician and songwriter, who was notably a pioneer in the development of the solid-body electric guitar. [e]

Les Paul [r]: (9 June 1915 – 13 August 2009) American innovator, inventor, musician and songwriter, who was notably a pioneer in the development of the solid-body electric guitar. [e] Zionism [r]: The ideology that Jews should form a Jewish state in what is traced as the Biblical area of Palestine; there are many interpretations, including the boundaries of such a state and its criteria for citizenship [e] (September 3)

Zionism [r]: The ideology that Jews should form a Jewish state in what is traced as the Biblical area of Palestine; there are many interpretations, including the boundaries of such a state and its criteria for citizenship [e] (September 3) Earth's atmosphere [r]: An envelope of gas that surrounds the Earth and extends from the Earth's surface out thousands of kilometres, becoming increasingly thinner (less dense) with distance but always held in place by Earth's gravitational pull. [e] (August 27)

Earth's atmosphere [r]: An envelope of gas that surrounds the Earth and extends from the Earth's surface out thousands of kilometres, becoming increasingly thinner (less dense) with distance but always held in place by Earth's gravitational pull. [e] (August 27) Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain [r]: U.S. educator deeply bonded to Bowdoin College, from undergraduate to President; American Civil War general and recipient of the Medal of Honor; Governor of Maine [e] (August 20)

Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain [r]: U.S. educator deeply bonded to Bowdoin College, from undergraduate to President; American Civil War general and recipient of the Medal of Honor; Governor of Maine [e] (August 20) The Sporting Life (album) [r]: A 1994 studio album recorded by Diamanda Galás and John Paul Jones. [e] (August 13}

The Sporting Life (album) [r]: A 1994 studio album recorded by Diamanda Galás and John Paul Jones. [e] (August 13} The Rolling Stones [r]: Famous and influential English blues rock group formed in 1962, known for their albums Let It Bleed and Sticky Fingers, and songs '(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction' and 'Start Me Up'. [e] (August 5)

The Rolling Stones [r]: Famous and influential English blues rock group formed in 1962, known for their albums Let It Bleed and Sticky Fingers, and songs '(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction' and 'Start Me Up'. [e] (August 5) Euler angles [r]: three rotation angles that describe any rotation of a 3-dimensional object. [e] (July 30)

Euler angles [r]: three rotation angles that describe any rotation of a 3-dimensional object. [e] (July 30) Chester Nimitz [r]: United States Navy admiral (1885-1966) who was Commander in Chief, Pacific and Pacific Ocean Areas in World War II [e] (July 23)

Chester Nimitz [r]: United States Navy admiral (1885-1966) who was Commander in Chief, Pacific and Pacific Ocean Areas in World War II [e] (July 23) Heat [r]: A form of energy that flows spontaneously from hotter to colder bodies that are in thermal contact. [e] (July 16)

Heat [r]: A form of energy that flows spontaneously from hotter to colder bodies that are in thermal contact. [e] (July 16) Continuum hypothesis [r]: A statement about the size of the continuum, i.e., the number of elements in the set of real numbers. [e] (July 9)

Continuum hypothesis [r]: A statement about the size of the continuum, i.e., the number of elements in the set of real numbers. [e] (July 9) Hawaiian alphabet [r]: The form of writing used in the Hawaiian Language [e] (July 2)

Hawaiian alphabet [r]: The form of writing used in the Hawaiian Language [e] (July 2) Now and Zen [r]: A 1988 studio album recorded by Robert Plant, with guest contributions from Jimmy Page. [e] (June 25)

Now and Zen [r]: A 1988 studio album recorded by Robert Plant, with guest contributions from Jimmy Page. [e] (June 25) Wrench (tool) [r]: A fastening tool used to tighten or loosen threaded fasteners, with one end that makes firm contact with flat surfaces of the fastener, and the other end providing a means of applying force [e] (June 18)

Wrench (tool) [r]: A fastening tool used to tighten or loosen threaded fasteners, with one end that makes firm contact with flat surfaces of the fastener, and the other end providing a means of applying force [e] (June 18) Air preheater [r]: A general term to describe any device designed to preheat the combustion air used in a fuel-burning furnace for the purpose of increasing the thermal efficiency of the furnace. [e] (June 11)

Air preheater [r]: A general term to describe any device designed to preheat the combustion air used in a fuel-burning furnace for the purpose of increasing the thermal efficiency of the furnace. [e] (June 11) 2009 H1N1 influenza virus [r]: A contagious influenza A virus discovered in April 2009, commonly known as swine flu. [e] (June 4)

2009 H1N1 influenza virus [r]: A contagious influenza A virus discovered in April 2009, commonly known as swine flu. [e] (June 4) Gasoline [r]: A fuel for spark-ignited internal combustion engines derived from petroleum crude oil. [e] (21 May)

Gasoline [r]: A fuel for spark-ignited internal combustion engines derived from petroleum crude oil. [e] (21 May) John Brock [r]: Fictional British secret agent who starred in three 1960s thrillers by Desmond Skirrow. [e] (8 May)

John Brock [r]: Fictional British secret agent who starred in three 1960s thrillers by Desmond Skirrow. [e] (8 May) McGuffey Readers [r]: A set of highly influential school textbooks used in the 19th and early 20th centuries in the elementary grades in the United States. [e] (14 Apr)

McGuffey Readers [r]: A set of highly influential school textbooks used in the 19th and early 20th centuries in the elementary grades in the United States. [e] (14 Apr) Vector rotation [r]: Process of rotating one unit vector into a second unit vector. [e] (7 Apr)

Vector rotation [r]: Process of rotating one unit vector into a second unit vector. [e] (7 Apr) Leptin [r]: Hormone secreted by adipocytes that regulates appetite. [e] (31 Mar)

Leptin [r]: Hormone secreted by adipocytes that regulates appetite. [e] (31 Mar) Kansas v. Crane [r]: A 2002 decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, ruling that a person could not be adjudicated a sexual predator and put in indefinite medical confinement, purely on assessment of an emotional disorder, but such action required proof of a likelihood of uncontrollable impulse presenting a clear and present danger. [e] (24 Mar)

Kansas v. Crane [r]: A 2002 decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, ruling that a person could not be adjudicated a sexual predator and put in indefinite medical confinement, purely on assessment of an emotional disorder, but such action required proof of a likelihood of uncontrollable impulse presenting a clear and present danger. [e] (24 Mar) Punch card [r]: A term for cards used for storing information. Herman Hollerith is credited with the invention of the media for storing information from the United States Census of 1890. [e] (17 Mar)

Punch card [r]: A term for cards used for storing information. Herman Hollerith is credited with the invention of the media for storing information from the United States Census of 1890. [e] (17 Mar) Jass–Belote card games [r]: A group of trick-taking card games in which the Jack and Nine of trumps are the highest trumps. [e] (10 Mar)

Jass–Belote card games [r]: A group of trick-taking card games in which the Jack and Nine of trumps are the highest trumps. [e] (10 Mar) Leptotes (orchid) [r]: A genus of orchids formed by nine small species that exist primarily in the dry jungles of South and Southeast Brazil. [e] (3 Mar)

Leptotes (orchid) [r]: A genus of orchids formed by nine small species that exist primarily in the dry jungles of South and Southeast Brazil. [e] (3 Mar) Worm (computers) [r]: A form of malware that can spread, among networked computers, without human interaction. [e] (24 Feb)

Worm (computers) [r]: A form of malware that can spread, among networked computers, without human interaction. [e] (24 Feb) Joseph Black [r]: Add brief definition or description (11 Feb 2009)

Joseph Black [r]: Add brief definition or description (11 Feb 2009) Sympathetic magic [r]: Add brief definition or description (17 Jan 2009)

Sympathetic magic [r]: Add brief definition or description (17 Jan 2009) Dien Bien Phu [r]: Add brief definition or description (25 Dec)

Dien Bien Phu [r]: Add brief definition or description (25 Dec)- Blade Runner [r]: Add brief definition or description (25 Nov)

Piquet [r]: Add brief definition or description (18 Nov)

Piquet [r]: Add brief definition or description (18 Nov) Crash of 2008 [r]: Add brief definition or description (23 Oct)

Crash of 2008 [r]: Add brief definition or description (23 Oct) Information Management [r]: Add brief definition or description (31 Aug)

Information Management [r]: Add brief definition or description (31 Aug) Battle of Gettysburg [r]: Add brief definition or description (8 July)

Battle of Gettysburg [r]: Add brief definition or description (8 July) Drugs banned from the Olympics [r]: Add brief definition or description (1 July)

Drugs banned from the Olympics [r]: Add brief definition or description (1 July) Sea glass [r]: Add brief definition or description (24 June)

Sea glass [r]: Add brief definition or description (24 June) Dazed and Confused (Led Zeppelin song) [r]: Add brief definition or description (17 June)

Dazed and Confused (Led Zeppelin song) [r]: Add brief definition or description (17 June) Hirohito [r]: Add brief definition or description (10 June)

Hirohito [r]: Add brief definition or description (10 June) Henry Kissinger [r]: Add brief definition or description (3 June)

Henry Kissinger [r]: Add brief definition or description (3 June)- Palatalization [r]: Add brief definition or description (27 May)

Intelligence on the Korean War [r]: Add brief definition or description (20 May)

Intelligence on the Korean War [r]: Add brief definition or description (20 May) Trinity United Church of Christ, Chicago [r]: Add brief definition or description (13 May)

Trinity United Church of Christ, Chicago [r]: Add brief definition or description (13 May) BIOS [r]: Add brief definition or description (6 May)

BIOS [r]: Add brief definition or description (6 May) Miniature Fox Terrier [r]: Add brief definition or description (23 April)

Miniature Fox Terrier [r]: Add brief definition or description (23 April) Joseph II [r]: Add brief definition or description (15 Apr)

Joseph II [r]: Add brief definition or description (15 Apr) British and American English [r]: Add brief definition or description (7 Apr)

British and American English [r]: Add brief definition or description (7 Apr) Count Rumford [r]: Add brief definition or description (1 April)

Count Rumford [r]: Add brief definition or description (1 April) Whale meat [r]: Add brief definition or description (25 March)

Whale meat [r]: Add brief definition or description (25 March) Naval guns [r]: Add brief definition or description (18 March)

Naval guns [r]: Add brief definition or description (18 March) Sri Lanka [r]: Add brief definition or description (11 March)

Sri Lanka [r]: Add brief definition or description (11 March) Led Zeppelin [r]: Add brief definition or description (4 March)

Led Zeppelin [r]: Add brief definition or description (4 March) Martin Luther [r]: Add brief definition or description (20 February)

Martin Luther [r]: Add brief definition or description (20 February) Cosmology [r]: Add brief definition or description (4 February)

Cosmology [r]: Add brief definition or description (4 February) Ernest Rutherford [r]: Add brief definition or description(28 January)

Ernest Rutherford [r]: Add brief definition or description(28 January) Edinburgh [r]: Add brief definition or description (21 January)

Edinburgh [r]: Add brief definition or description (21 January) Russian Revolution of 1905 [r]: Add brief definition or description (8 January 2008)

Russian Revolution of 1905 [r]: Add brief definition or description (8 January 2008) Phosphorus [r]: Add brief definition or description (31 December)

Phosphorus [r]: Add brief definition or description (31 December) John Tyler [r]: Add brief definition or description (6 December)

John Tyler [r]: Add brief definition or description (6 December) Banana [r]: Add brief definition or description (22 November)

Banana [r]: Add brief definition or description (22 November) Augustin-Louis Cauchy [r]: Add brief definition or description (15 November)

Augustin-Louis Cauchy [r]: Add brief definition or description (15 November)- B-17 Flying Fortress (bomber) [r]: Add brief definition or description - 8 November 2007

Red Sea Urchin [r]: Add brief definition or description - 1 November 2007

Red Sea Urchin [r]: Add brief definition or description - 1 November 2007 Symphony [r]: Add brief definition or description - 25 October 2007

Symphony [r]: Add brief definition or description - 25 October 2007 Oxygen [r]: Add brief definition or description - 18 October 2007

Oxygen [r]: Add brief definition or description - 18 October 2007 Origins and architecture of the Taj Mahal [r]: Add brief definition or description - 11 October 2007

Origins and architecture of the Taj Mahal [r]: Add brief definition or description - 11 October 2007 Fossilization (palaeontology) [r]: Add brief definition or description - 4 October 2007

Fossilization (palaeontology) [r]: Add brief definition or description - 4 October 2007 Cradle of Humankind [r]: Add brief definition or description - 27 September 2007

Cradle of Humankind [r]: Add brief definition or description - 27 September 2007 John Adams [r]: Add brief definition or description - 20 September 2007

John Adams [r]: Add brief definition or description - 20 September 2007 Quakers [r]: Add brief definition or description - 13 September 2007

Quakers [r]: Add brief definition or description - 13 September 2007 Scarborough Castle [r]: Add brief definition or description - 6 September 2007

Scarborough Castle [r]: Add brief definition or description - 6 September 2007 Jane Addams [r]: Add brief definition or description - 30 August 2007

Jane Addams [r]: Add brief definition or description - 30 August 2007 Epidemiology [r]: Add brief definition or description - 23 August 2007

Epidemiology [r]: Add brief definition or description - 23 August 2007 Gay community [r]: Add brief definition or description - 16 August 2007

Gay community [r]: Add brief definition or description - 16 August 2007 Edward I [r]: Add brief definition or description - 9 August 2007

Edward I [r]: Add brief definition or description - 9 August 2007

Rules and Procedure

Rules

- The primary criterion of eligibility for a new draft is that it must have been ranked as a status 1 or 2 (developed or developing), as documented in the History of the article's Metadate template, no more than one month before the date of the next selection (currently every Thursday).

- Any Citizen may nominate a draft.

- No Citizen may have nominated more than one article listed under "current nominees" at a time.

- The article's nominator is indicated simply by the first name in the list of votes (see below).

- At least for now--while the project is still small--you may nominate and vote for drafts of which you are a main author.

- An article can be the New Draft of the Week only once. Nominated articles that have won this honor should be removed from the list and added to the list of previous winners.

- Comments on nominations should be made on the article's talk page.

- Any draft will be deleted when it is past its "last date eligible". Don't worry if this happens to your article; consider nominating it as the Article of the Week.

- If an editor believes that a nominee in his or her area of expertise is ineligible (perhaps due to obvious and embarrassing problems) he or she may remove the draft from consideration. The editor must indicate the reasons why he has done so on the nominated article's talk page.

Nomination

See above section "Add New Nominees Here".

Voting

- To vote, add your name and date in the Supporters column next to an article title, after other supporters for that article, by signing

<br />~~~~. (The date is necessary so that we can determine when the last vote was added.) Your vote is alloted a score of 1. - Add your name in the Specialist supporters column only if you are an editor who is an expert about the topic in question. Your vote is alloted a score of 1 for articles that you created and 2 for articles that you did not create.

- You may vote for as many articles as you wish, and each vote counts separately, but you can only nominate one at a time; see above. You could, theoretically, vote for every nominated article on the page, but this would be pointless.

Ranking

- The list of articles is sorted by number of votes first, then alphabetically.

- Admins should make sure that the votes are correctly tallied, but anyone may do this. Note that "Specialist Votes" are worth 3 points.

Updating

- Each Thursday, one of the admins listed below should move the winning article to the Current Winner section of this page, announce the winner on Citizendium-L and update the "previous winning drafts" section accordingly.

- The winning article will be the article at the top of the list (ie the one with the most votes).

- In the event of two or more having the same number of votes :

- The article with the most specialist supporters is used. Should this fail to produce a winner, the article appearing first by English alphabetical order is used.

- The remaining winning articles are guaranteed this position in the following weeks, again in alphabetical order. No further voting should take place on these, which remain at the top of the table with notices to that effect. Further nominations and voting take place to determine future winning articles for the following weeks.

- Winning articles may be named New Draft of the Week beyond their last eligible date if their circumstances are so described above.

- The article with the most specialist supporters is used. Should this fail to produce a winner, the article appearing first by English alphabetical order is used.

Administrators

The Administrators of this program are the same as the admins for CZ:Article of the Week.

References

See Also

- CZ:Article of the Week

- CZ:Markup tags for partial transclusion of selected text in an article

- CZ:Monthly Write-a-Thon