Archive:New Draft of the Week: Difference between revisions

imported>Daniel Mietchen (Ellesmere Chaucer manuscript) |

imported>Daniel Mietchen (Debt; need new suggestions!) |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| <!-- article --> | | <!-- article --> | ||

| <!-- score --> | | <!-- score --> | ||

| <!-- supporters --> | | <!-- supporters --> | ||

| <!-- specialist supporters --> | | <!-- specialist supporters --> | ||

| <!-- date created --> | | <!-- date created --> | ||

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

== View Current Transcluded Nominees (after they have been transcluded by an Administrator) == | == View Current Transcluded Nominees (after they have been transcluded by an Administrator) == | ||

The next New Draft of the Week will be the article with the most votes at 1 AM UTC on Thursday, | The next New Draft of the Week will be the article with the most votes at 1 AM UTC on Thursday, 29 July, 2010. | ||

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

{{Featured Article Candidate | {{Featured Article Candidate | ||

| article = | | article = Debt | ||

| supporters = [[User:Daniel Mietchen|Daniel Mietchen]] | | supporters = --[[User:Daniel Mietchen|Daniel Mietchen]] 23:55, 18 June 2010 (UTC) | ||

| specialists = | | specialists = | ||

| created = | | created = June 9, 2010 | ||

| score = 1 | | score = 1 | ||

}} | }} | ||

| Line 77: | Line 77: | ||

<div style="height:25em; overflow:auto; background:#f9f9f9; border:1px solid #aaa;"> | <div style="height:25em; overflow:auto; background:#f9f9f9; border:1px solid #aaa;"> | ||

{{rpr|Ellesmere Chaucer manuscript}} | |||

{{rpr|Ellipse}} | {{rpr|Ellipse}} | ||

{{rpr|Aeneid}} | {{rpr|Aeneid}} | ||

Revision as of 06:26, 16 July 2010

The New Draft of the Week is a chance to highlight a recently created Citizendium article that has just started down the road of becoming a Citizendium masterpiece.

It is chosen each week by vote in a manner similar to that of its sister project, the Article of the Week.

Add New Nominees Here

To add a new nominee or vote for an existing nominee, click edit for this section and follow the instructions Ellesmere Chaucer manuscript Ellipse

| Nominated article | Vote Score |

Supporters | Specialist supporters | Date created |

|---|---|---|---|---|

If you want to see how these nominees will look on the CZ home page (if selected as a winner), scroll down a little bit.

Transclusion of the above nominees (to be done by an Administrator)

- Transclude each of the nominees in the above "Table of Nominee" as per the instructions at Template:Featured Article Candidate.

- Then add the transcluded article to the list in the next section below, using the {{Featured Article Candidate}} template.

View Current Transcluded Nominees (after they have been transcluded by an Administrator)

The next New Draft of the Week will be the article with the most votes at 1 AM UTC on Thursday, 29 July, 2010.

| Nominated article | Supporters | Specialist supporters | Dates | Score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A debt is anything that is owed, and being in debt is the state of owing something to another. There are moral debts, such as debts of honour and debts of gratitude, but the most obvious form of debt in most people's minds is economic or financial debt, when one party owes goods, services or money, to another. In that context it is a means of transferring resources from those who own them, but do not wish to use them, to those who wish to use them, but do not own them. The terminology of debtA voluntary loan agreement may be presumed to give benefits to both borrower and lender, and to have no direct effect on other parties. A loan benefits the borrower at the expense of the lender, in return for which the borrower may be expected to compensate the lender by the payment of sum of money in addition to the eventual repayment of the loan, that is termed "interest". The amount of interest payable annually is termed the interest or discount rate. The loan agreement may also be expected to take account of the possibility that the borrower may fail to repay the loan ("default" upon its terms) by failing to fulfill its obligations concerning the payment of interest or the return of the original payment (termed the "principal"). The agreement may include the provision of "collateral", which will give the lender title to (ownership of) an asset belonging to the lender, if the borrower defaults (the term "mortgage" may be used if the asset is property). Alternatively, or in addition to the provision of collateral, the agreed interest rate may embody a "risk premium" in addition to the appropriate "risk-free interest rate". Toxic debt is debt whose repayment with due interest is deemed unlikely. The date on which a debt is due to be repaid is termed its "maturity" date. The term "roll-over" refers to the replacement of a matured debt by another of similar value, and a "revolving debt" is one which is automatically rolled-over whenever it matures. The term leverage is used to refer to a proportional measure of indebtedness. Leveraging is the process of increasing indebtedness, and deleveraging is the process of reducing indebtedness. Categories of debtHousehold debt

Corporate debtCorporations make loan agreements by the issue and sale of securities that are termed bonds if their term to maturity exceeds one year, and commercial paper if that term is shorter. A secured debt entitles the creditor to receive a specified items of corporation property if the corporation defaults on the terms of its debt. The terms of a corporate bond may include a call option enabling its holder to require its repayment before it matures (in which case it is termed a callable bond), or the right to exchange it for an equivalent amount of the corporation's equity under specified conditions (in which case it is termed a convertible bond). Bonds represent a claim upon a corporation's assets in the event that the corporation ceases trading in an order of priority determined by the terms of the bond and the legal regime under which they are issued. There are national differences of practice and terminology in that respect. Public debtThe term public debt (often referred to domestically as "the national debt") is used to refer to the borrowings of governments in general. International debtAccess to the bond and money markets is in principle available to governments and established corporations throughout the world, but in practical terms direct access is available only to those with acceptable credit ratings. Other sources of finance that are available to developing countries include:

The market for debtLegal aspectsBorrowers' rightsMost legal systems impose limits on the ability of a creditor to seize the property of a debtor who is unable to repay a debt. Some exempt a minimum amount of real estate and some also exempt some categories of movable property such as tools of trade. There are often usury laws that limit the amount of interest that may be charged[3]. Creditors' rightsThe legal protection of creditors against default by borrowers varies from country to country and among states within countries, but its main features are the provision for:

For the protection of prospective creditors, loan agreements usually have to be placed upon a register to make public any prior claims upon the borrower's assets, and it is illegal for a company to continue trading if its directors know it to be insolvent. Sovereign debtThe law offers no protection to the creditors of foreign governments, and it is legally open to any government to repudiate its debts. Since countries cannot cease trading, however, the concept of bankruptcy is inapplicable to countries; and while a country may be unable to pay its debts on time, it necessarily retains the capacity to make eventual or partial payment. To avoid some of the costs of sovereign default, creditor and debtor countries may agree to restructure the debt (for example by reducing the level and extending the period of interest payments). The "Paris Club[4]" is an informal organisation of creditor countries that negotiates such agreements. The concept of "odious debt[5]" has sometimes been used to argue that debts incurred by a government were illegal because they had not been undertaken in the interests of its country, but an international discussion[6] in 2008 did not reach agreement about the implications of the concept. Attitudes to debtThe historical traditionA debt that is freely undertaken may be presumed to confer benefits upon both parties and to no harm no-one, in which case it is not obvious that it should be an object of disapproval. There is similarly no obvious reason for objecting to agreed interest payments, since they may be presumed to be in accordance with the time preferences of both parties. Interest-bearing debt has nevertheless been widely condemned at several stages in the course of history. The divine instructions received by Moses, as recorded in the Bible, include:

- which have, from time to time, been interpreted by western religious authorities[8][9] as forbidding all charging of interest. There has been much debate concerning the interpretation of the term "usury", and as late as the 1920s, the then popular Catholic author, Hillaire Belloc, wrote that:

Secular objections to debt have been expressed by Shakespeare in Polonius's advice to his son:

- and by Danté', whose Divine Comedy places usurers below murderers, in the third round of violence in the seventh circle of hell where:

- and by Benjamin Franklin:

Attitudes to public debt have also been generally hostile, for example Thomas Jefferson believed that :

However, the utilitarian philosopher, Jeremy Bentham, took the contrary view about personal debt, arguing that:

Behavioural influencesMany examples have been recorded of behaviour that is contrary to the presumption that interest-paying loans will be accepted if they offer net benefits to borrowers. The phenomenon of debt aversion has, for example, been observed among students, many of whom have been found to be unwilling to accept loans from which they would expect to benefit[16]. It has also been concluded that most people undertake routine debt without due regard to its relative costs and benefits[17]. Other forms of logically inconsistent behaviour have also been observed. The term Time inconsistency has been applied to observed patterns in the treatment of loan agreements in which different time preference rates have been applied to different stages in their execution[18]. The term "hyperbolic discounting" (as distinct from conventional "exponential discounting") denotes the use of a higher annual rate of time preference against short delays than against longer delays. It has been pointed out that, although hyperbolic discounting is time inconsistent when applied in terms of relative time, it is not time inconsistent when applied in terms of absolute time (such as the application of a lower rate to a later period in the subject's life)[19]. Current attitudesHousehold debt in the United States, Britain and Japan amounts, on average, to more than a year's disposable income, and to about 30 per cent of that level in Germany and Italy[20]. It consists mainly of long-term house mortgages (which householders may not consider to be debt) but includes a substantial amount of revolving (ie regularly renewable) debt in the form of delayed payments for credit card purchases[21]. Debt continues to be a matter of concern on the part of its holders and nearly half of credit card holders in the United States are reported to suffer feelings of guilt about their use[22]. There is also evidence of debt aversion among United States businessmen, and a substantial number of large public non-financial US firms follow a zero-debt policy [23] Historically high levels of public debt are also a matter of general concern, and an opinion poll in February 2009, reported that it was one of the top two matters of concern to United States voters [24]. According to Robert Schiller, Professor of Economics at Yale University, investors tend to over-react to statistics relating public debt to gdp, and to persuade governments to make premature reductions in public expenditure in the aftermath of recessions [25].

The economics of debt

As a means of transferring resources from those who own them. but do not wish to use them, to those who wish to use them, but do not own them; debt may be expected to promote economic growth by facilitating investment. As a means of "consumption smoothing", that enables a household to forego consumption when its income is relatively high, in order to enjoy an acceptable standard of living when the wage earner retires or is unemployed; it may be expected to promote personal and collective welfare. The most effective development of debt for those purposes tends to occur in stable communities with adequate financial intermediaries and means of the enforcing loan agreements[26]. The accumulation of debt can, however, be a cause of damaging instability. According to Hyman Minsky's financial instability hypothesis[27], borrowers accumulate debt in prosperous times, and allow it rise to a point at which it cannot be repaid out of current income. Debt reduction (or "deleveraging" nearly always follows a financial crisis[28], and inevitably creates reductions of consumption and thus of economic activity [29] [30]. International debt has assumed economic importance in recent years, as massive international capital flows[31] have affected domestic economies. Until the 1990s the major direction of flow arose from borrowing by the developing countries from the industrialised countries, but the direction of flow has subsequently reversed after the governments of developing countries began to use domestic savings to buy the bond issues of the industrialised countries [32]. Factors that have influenced high levels of saving by the developing countries[33] have included the lack of consumption smoothing institutions such as insurance, income support and pension funds. The main factor that has influenced the large proportion of those savings that has been lent abroad has been the lack of domestic investment opportunities. Those are changing influences, and changes in the volumes of such flows of capital are a potential source of economic instability[34]. If the annual interest payable on a government's debt rises faster than the national income, the point will eventually be reached at which it would exceed the revenue that could be raised by taxation. The debt trap identity establishes that the budget surplus (or reduced deficit) needed to avoid an increase in the ratio of debt to GDP depends upon the level of that ratio and the difference between the interest rate payable on the debt and the growth rate of nominal GDP. An increase in the risk premium that the bond market applies to a government's borrowing may increase the cost of its borrowing to an extent that increases the market's perception of its riskiness, in response to which the bond market may apply a further increase in its risk premium. (An expectation of a reduction in economic growth could also trigger such a response). Repetition of that sequence could eventually force the government to default by placing the cost of a roll-over of maturing debt beyond its capacity to raise the necessary funds. The market's awareness of that possibilty may add to the destabilising effect of its actions. References

|

--Daniel Mietchen 23:55, 18 June 2010 (UTC) | 1

|

Current Winner

To be selected and implemented by an Administrator. To change, click edit and follow the instructions, or see documentation at {{Featured Article}}.

| The metadata subpage is missing. You can start it via filling in this form or by following the instructions that come up after clicking on the [show] link to the right. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

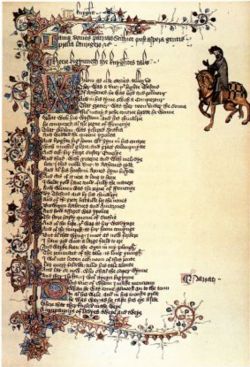

The Ellesmere Chaucer manuscript, also Ellesmere Chaucer or Ellesmere manuscript, is an early 15th century illuminated manuscript of Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales. It is part of the Ellesmere manuscripts and referred to as MS EL 26 C 9. Together with the Hengwrt Chaucer manuscript, it is considered to be the most important source of the original text of The Canterbury Tales. The Ellesmere Chaucer is held in the Huntington Library in San Marino, California (U.S. state). It is named after its former owner, the Earl of Ellesmere.

Significance of the Ellesmere Chaucer

The Ellesmere Chaucer is one of the oldest surviving manuscripts of The Canterbury Tales. It was copied in the years following Chaucer's death in 1400, according to some in 1401, [1] to others around 1410.[2] Since no holograph of Chaucer has ever been found, it offers the best evidence of what he wrote.

Still it was only with the publication of Walter W. Skeat's edition of the Works of Geoffrey Chaucer in 1894, that the Ellesmere Chaucer gained its eminent textual status. After Skeat many editions were based on the Ellesmere Chaucer, including the Riverside Chaucer in 1987. Other editions were based on the Hengwrt Chaucer manuscript. In fact, no matter which of these is chosen, the other one is heavily consulted. [3]

History of the manuscript

The early history of the Ellesmere Chaucer manuscript is uncertain, but it is possible that soon after Chaucer's death in 1400, his son Thomas commissioned a deluxe manuscript of The Canterbury Tales, and provided the materials to produce it. [4] Over a large period of time names were recorded in the manuscript, which implies that it must have had several owners. The following is a reconstruction of that ownership with the use of the most important of those glosses.

House de Vere

Since a ballad on the House of Vere is included at the beginning of the manuscript, an early association with John de Vere (1408-1462), 12th Earl of Oxford is probable. After the death of his father in 1417, he became ward of the Duke of Exeter, and in 1426 of the Duke of Bedford, both kinsmen of Thomas Chaucer.

At the time of death of John de Vere (1442-1513), 13th Earl of Oxford, Sir Robert Drury was one of the executors of the will and among the legatees were Sir Drury's sons-in-law, George Waldegrave and Sir Giles Alington. [2]

Drury Family

From 1513 on the manuscript seems to have been in the possession of the Drury family.

- “Robertus drury miles [space], William drury miles, Robertus drury miles, domina Jarmin, domina Jarningam, dommina Alington,”

This gloss refers to Sir Robert Drury of Hawsted in Suffolk, his two sons William and Robert, and his three daughters, Anna, Bridget and Ursula. In 1495 Sir Drury had been speaker of the House of Commons and he was also a member of Henry VIII's Council. Anna Drury was married to George Waldegrave, and after Waldegrave's death in 1528 to Sir Thomas Jermyn. Bridget Drury was married to Sir John Jernyngham of Somerleyton and Ursula Drury was married to Sir Giles Alington. The names Domina Jernegan and Domina Alington are repeated in the manuscript. The gloss "Edwarde Waldegrave" probably refers to George Waldegrave's and Anne Drury's son, who was born in 1514.

- "... per me henricum Payne" "And also my Chaucer written in vellum and illumyned with golde."

This could be Henry Payne of Nowton, near Hawstead, a member of 'The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn', who died in 1568. He had witnessed Sir William Drury's will in 1557 and had gotten a legacy from him. In his own will, he bequeathed the manuscript to Sir Giles Alington, the grandson of Ursula Drury and her husband Giles Alington.

- "1 Durum 5 Pati 68 R. North"

This gloss gives us the date 1568 and the motto "Durum pati" of Roger North (1530/31-1600), 2nd Lord North, the new owner of the manuscript, although it is not known how it came into his possession. Some verses were added to the manuscript, signed with 'R.N.' or 'R. North'. [2]

The Bridgewater Library

After the death of Lord North in 1600, the manuscript came into the possession of John Egerton (1579-1649), who was created 1st Earl of Bridgewater in 1617. He added the pressmark "Q3" to the manuscript. John Egerton (1622-1696), 2nd Earl of Bridgewater corrected that later to "Q.3/3". The manuscript became part of the Bridgewater library and was housed at Ashridge in Hertford, where it would stay until 1802. It was then moved to London. A year later Francis Egerton (1736-1803), 6th Earl and 3rd Duke of Bridgewater died unmarried. His distant cousin, John William Egerton (1753-1823), inherited the earldom of Bridgewater and the Ashridge lands. His nephew, George Granville Leveson-Gower, 2nd Marquis of Stafford (later 1st Duke of Sutherland), inherited the Bridgewater library and other properties including Bridgewater House in London. From 1803 to 1833 the manuscript was called the Stafford Chaucer. Leveson-Gower’s younger son, Francis Egerton, created Earl of Ellesmere in 1846, inherited the library and the Stafford Chaucer became the Ellesmere Chaucer. The library remained in the family until it was sold by John Francis Granville Scrope Egerton (1872-1944), 4th Earl of Ellesmere. [2]

Henry E. Huntington and the Huntington Library

In 1917, Henry Edwards Huntington, railroad magnate and collector of art and rare books, purchased the Bridgewater library privately from Sotheby's. That makes him the last private owner of the manuscript that is now known as the Ellesmere Chaucer. After Huntington's death in 1927, his priceless library of rare books and art was opened to the public.

Description of the manuscript

The beautiful, large manuscript, probably made and bound in London, is approximately four hundred by two hundred eighty-four millimetres in size. It contains two hundred and forty fine vellum leaves, two hundred thirty-two of which contain the text of The Canterbury Tales. It is written in an anglicana formata script [5] by the scribe who also copied the Hengwrt Chaucer manuscript. In 2004 this scribe has been tentatively identified as Adam Pinkhurst. The remaining leaves contain verses, notes and scribbles by various persons. It is luxuriously illuminated and by far the most famous survivor of the rare illustrated versions of Chaucer's major works. In circa 1911 it was bound in dark green morocco, with the Egerton arms stamped in gold on the front cover. [6] In 1994 the previous modern green goatskin binding of the manuscript was removed and in 1995 the manuscript was re-bound, using original 15th-century techniques. [2]

The illumination

After the text was copied [7] it was surrounded by decorated borders of floral patterns in a conservative style. [6]

The white-highlighted initials on a gold ground in blue, pink, dull red, and with little or no green, are six to four lines high. They are filled with leaf designs, with bars and foliage borders in the same colours, including daisy buds, interlaced and with an occasional grotesque.

Smaller gold initials are two to four lines high and have white patterns on particoloured blue and pink grounds.

Paragraph marks are alternating in blue with red or in gold with grey-blue flourishing and further in the text in gold with purple. Running headlines and marginal notes are set off by these paragraph marks. [2]

Verse paragraph breaks are identified by the term 'pausacio'. [8]

The portraits of the pilgrims

A unique feature of the Ellesmere Chaucer is the set of twenty-three equestrian portraits of the pilgrims. Along with some symbolism - the Clerk with books, the Physician with a urine bottle - some replicate many of the details of the descriptions given in the General Prologue and the links between the tales. [9] Even the horses suit their riders, at least to some extent.

Each portrait is positioned at the start of his or her tale and placed outside of the written space. On the recto the illuminations are on the right of the text in the gloss space or in the ruled texts space. On the verso they are usually to the left of the text in a niche in the decoration, except for the portrait of the Miller, which is also pictured on the right of the text.

The portraits vary in size, the largest being circa hundred by eighty millimetres, the smallest circa forty-five by forty-five millimetres according to the artist.

There were three different artists at work. One painted the first sixteen pilgrims and the last one as small figures. A second one painted only Chaucer's portrait. A third one was responsible for the illustrations of the Monk, the Nun's Priest, the Second Nun, the Canon's Yeoman and the Manciple. He painted his figures on a larger scale en made them standing on a patch of green grass.

Some miniatures seem to be done before the border decoration was painted, and forced the bar border and initial to the right of their normal position. Others were painted after the border. Then erasure of parts of the border was needed. [2]

Pilgrim Chaucer's portrait

The portrait of pilgrim Chaucer, [10] the pilgrim that records all the tales, is painted by the most competent of the three artists that worked on the Ellesmere Chaucer. There is some discrepancy in proportion between the large bust of pilgrim Chaucer and the smaller size of his legs and his horse, standing on a grassy plot. It marks the opening of his The Tale of Melibee. This bearded portrait of Geoffrey bears a marked resemblance to the image appearing in a British Library manuscript of Thomas Hoccleve's poem The Regiments of Princes. (MS Harley 4866). [11] That picture [12] accompanies a eulogy of Chaucer and is descibed by Hoccleve as a lyknesse that will serve to remind readers of what Chaucer looked like. [13]

The order of the tales

The Ellesmere and Hengwrt Chaucer manuscripts share the same scribe. Pinkhurst appears to have copied the Hengwrt Chaucer first, maybe from Chaucer's originals and possibly during his lifetime. He then copied the Ellesmere manuscript after a more careful inventory and editorial preparation.

Academics divide the tales into ten fragments. The tales in a fragment are connected, and give a clear indication of their order, usually with one character that passes the floor to another. Between the fragments themselves there are no explicit connections, save for IX-X and, in the Ellesmere manuscript, IV-V. This means that there is no explicit indication of the order in which Chaucer intended the fragments to be read. The order of the tales in the Hengwrt and the Ellesmere manuscripts differs. The order of the Ellesmere Chaucer, also the most popular one and used in The Riverside Chaucer, is as follows:

| Fragment | Tales |

|---|---|

| I (A) | General Prologue The Knight's Tale The Miller's Prologue and Tale The Reeve's Prologue and Tale The Cook's Prologue and Tale |

| II (B1) | The Man of Law's Introduction, Prologue, Tale and Epilogue |

| III (D) | The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale The Friar's Prologue and Tale The Summoner's Prologue and Tale |

| IV (E) | The Clerk's Prologue and Tale The Merchant's Prologue, Tale and Epilogue |

| V (F) | The Squire's Introduction and Tale The Franklin's Prologue and Tale |

| VI (C) | The Physician's Tale The Pardoner's Introduction, Prologue and Tale |

| VII (B2) | The Shipman's Tale The Prioress's Prologue and Tale The Prologue and Tale of Sir Thopas The Tale of Milibee The Monk's Prologue and Tale The Nun's Priest's Prologue, Tale and Epilogue |

| VIII (G) | The Second Nun's Prologue and Tale The Canon's Yeoman's Prologue and Tale |

| IX (H) | The Manciple's Prologue and Tale |

| X (I) | The Parson's Prologue and Tale Chaucer's Retraction |

The Ellesmere Chaucer fascimile

In commemoration of its 75th anniversary, the Huntington Library authorized Yushodo Co. in Tokyo to publish a facsimile of the Ellesmere Chaucer. This facsimile was printed in a full-color, high-definition process with gold inlay, on high quality, long-life paper imported from England. The original camera work was done at the Huntington Library by the Huntington's principle photographer, Robert Schlosser. The manuscript was conserved and rebound by Anthony G. Cains of the Trinity College, Dublin, with the assistance of Maria Fredericks, at the time Rare Book Conservator of the Huntington Library. This is truly an international work, bringing together the expertise of all participants to produce one magnificent facsimile. [4]

This fascimile was produced in a limited edition of 250 copies:

- the Deluxe version, sewn and bound in an early 15th-century-type binding, oak boards and quarter brown calf leather, with blue quarter morocco clamshell case,

- the Quired version of unsewn leaves in a blue quarter morocco clamshell case.

The Ellesmere Chaucer Monochromatic Facsimile

The transparencies that were the basis of the color facsimile were used to make a full-sized, monochromatic facsimile, printed by the Stinehour Press of Lunenberg, Vermont. The facsimile exibits the texture and decoration of the original manuscript pages. It features a color frontispiece, the page that begins the Knight's Tale. The New Ellemere Chaucer Facimile was released in 1996.

Sources and references

- The Riverside Chaucer Third Edition (1987), General Editor Larry D. Benson, Harvard University, Houghton Mufflin Company, Boston. ISBN 0-395-29031-7

- Ellesmere Chaucer - Guide to Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in the Huntington Library.

- Ruth Evans, "Chaucer's life", in: Steve Ellis Chaucer An Oxford Guide (2005). New York United States: Oxford University Press. Inc. ISBN 0-19-925912-7

- David Griffith, "Visual culture", in: Steve Ellis Chaucer An Oxford Guide (2005). New York United States: Oxford University Press. Inc. ISBN 0-19-925912-7

- Stephen Penn, "Literacy and literary production", in: Steve Ellis Chaucer An Oxford Guide (2005). New York United States: Oxford University Press. Inc. ISBN 0-19-925912-7

- Elizabeth Scala, "Editing Chaucer", in: Steve Ellis Chaucer An Oxford Guide (2005). New York United States: Oxford University Press. Inc. ISBN 0-19-925912-7

- ↑ Evans, p. 21.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Ellesmere Chaucer.

- ↑ Scala, p. 485.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Scala, p. 491.

- ↑ anglicana formata script

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Huntington Catalog Images

- ↑ Penn, p. 125

- ↑ Penn, p. 119.

- ↑ Griffith, p. 201.

- ↑ Portrait of Chaucer in the Ellesmere Chaucer.

- ↑ Griffith, p. 205.

- ↑ Geoffrey Chaucer's portrait in MS Harley 4866.

- ↑ Evans, p. 21.

- ↑ Ellesmere Chaucer

- ↑ Riverside, p. 5.

Previous Winners

Ellesmere Chaucer manuscript [r]: Early 15th century illuminated manuscript of Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales. [e]

Ellesmere Chaucer manuscript [r]: Early 15th century illuminated manuscript of Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales. [e] Ellipse [r]: Planar curve formed by the points whose distances to two given points add up to a given number. [e]

Ellipse [r]: Planar curve formed by the points whose distances to two given points add up to a given number. [e] Aeneid [r]: An epic poem written by Virgil, which depicts the hero Aeneas fleeing from Troy (ancient city), journeying to Carthage, Sicily, and finally to Italy where after battling, he becomes the precursor of the city of Rome; a monumental work of major significance in Western literature. [e]

Aeneid [r]: An epic poem written by Virgil, which depicts the hero Aeneas fleeing from Troy (ancient city), journeying to Carthage, Sicily, and finally to Italy where after battling, he becomes the precursor of the city of Rome; a monumental work of major significance in Western literature. [e] Tall tale [r]: A narrative, song or jest, transmitted orally or in writing, presenting an incredible, boastful or impossible story. [e]

Tall tale [r]: A narrative, song or jest, transmitted orally or in writing, presenting an incredible, boastful or impossible story. [e] Plane (geometry) [r]: In elementary geometry, a flat surface that entirely contains all straight lines passing through two of its points. [e]

Plane (geometry) [r]: In elementary geometry, a flat surface that entirely contains all straight lines passing through two of its points. [e] Steam [r]: The vapor (or gaseous) phase of water (H2O). [e]

Steam [r]: The vapor (or gaseous) phase of water (H2O). [e] Wasan [r]: Classical Japanese mathematics that flourished during the Edo Period from the 17th to mid-19th centuries. [e]

Wasan [r]: Classical Japanese mathematics that flourished during the Edo Period from the 17th to mid-19th centuries. [e] Racism in Australia [r]: The history of racism and restrictive immigration policies in the Commonwealth of Australia. [e]

Racism in Australia [r]: The history of racism and restrictive immigration policies in the Commonwealth of Australia. [e]- Think tank [r]: Add brief definition or description

Les Paul [r]: (9 June 1915 – 13 August 2009) American innovator, inventor, musician and songwriter, who was notably a pioneer in the development of the solid-body electric guitar. [e]

Les Paul [r]: (9 June 1915 – 13 August 2009) American innovator, inventor, musician and songwriter, who was notably a pioneer in the development of the solid-body electric guitar. [e] Zionism [r]: The ideology that Jews should form a Jewish state in what is traced as the Biblical area of Palestine; there are many interpretations, including the boundaries of such a state and its criteria for citizenship [e] (September 3)

Zionism [r]: The ideology that Jews should form a Jewish state in what is traced as the Biblical area of Palestine; there are many interpretations, including the boundaries of such a state and its criteria for citizenship [e] (September 3) Earth's atmosphere [r]: An envelope of gas that surrounds the Earth and extends from the Earth's surface out thousands of kilometres, becoming increasingly thinner (less dense) with distance but always held in place by Earth's gravitational pull. [e] (August 27)

Earth's atmosphere [r]: An envelope of gas that surrounds the Earth and extends from the Earth's surface out thousands of kilometres, becoming increasingly thinner (less dense) with distance but always held in place by Earth's gravitational pull. [e] (August 27) Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain [r]: U.S. educator deeply bonded to Bowdoin College, from undergraduate to President; American Civil War general and recipient of the Medal of Honor; Governor of Maine [e] (August 20)

Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain [r]: U.S. educator deeply bonded to Bowdoin College, from undergraduate to President; American Civil War general and recipient of the Medal of Honor; Governor of Maine [e] (August 20) The Sporting Life (album) [r]: A 1994 studio album recorded by Diamanda Galás and John Paul Jones. [e] (August 13}

The Sporting Life (album) [r]: A 1994 studio album recorded by Diamanda Galás and John Paul Jones. [e] (August 13} The Rolling Stones [r]: Famous and influential English blues rock group formed in 1962, known for their albums Let It Bleed and Sticky Fingers, and songs '(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction' and 'Start Me Up'. [e] (August 5)

The Rolling Stones [r]: Famous and influential English blues rock group formed in 1962, known for their albums Let It Bleed and Sticky Fingers, and songs '(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction' and 'Start Me Up'. [e] (August 5) Euler angles [r]: three rotation angles that describe any rotation of a 3-dimensional object. [e] (July 30)

Euler angles [r]: three rotation angles that describe any rotation of a 3-dimensional object. [e] (July 30) Chester Nimitz [r]: United States Navy admiral (1885-1966) who was Commander in Chief, Pacific and Pacific Ocean Areas in World War II [e] (July 23)

Chester Nimitz [r]: United States Navy admiral (1885-1966) who was Commander in Chief, Pacific and Pacific Ocean Areas in World War II [e] (July 23) Heat [r]: A form of energy that flows spontaneously from hotter to colder bodies that are in thermal contact. [e] (July 16)

Heat [r]: A form of energy that flows spontaneously from hotter to colder bodies that are in thermal contact. [e] (July 16) Continuum hypothesis [r]: A statement about the size of the continuum, i.e., the number of elements in the set of real numbers. [e] (July 9)

Continuum hypothesis [r]: A statement about the size of the continuum, i.e., the number of elements in the set of real numbers. [e] (July 9) Hawaiian alphabet [r]: The form of writing used in the Hawaiian Language [e] (July 2)

Hawaiian alphabet [r]: The form of writing used in the Hawaiian Language [e] (July 2) Now and Zen [r]: A 1988 studio album recorded by Robert Plant, with guest contributions from Jimmy Page. [e] (June 25)

Now and Zen [r]: A 1988 studio album recorded by Robert Plant, with guest contributions from Jimmy Page. [e] (June 25) Wrench (tool) [r]: A fastening tool used to tighten or loosen threaded fasteners, with one end that makes firm contact with flat surfaces of the fastener, and the other end providing a means of applying force [e] (June 18)

Wrench (tool) [r]: A fastening tool used to tighten or loosen threaded fasteners, with one end that makes firm contact with flat surfaces of the fastener, and the other end providing a means of applying force [e] (June 18) Air preheater [r]: A general term to describe any device designed to preheat the combustion air used in a fuel-burning furnace for the purpose of increasing the thermal efficiency of the furnace. [e] (June 11)

Air preheater [r]: A general term to describe any device designed to preheat the combustion air used in a fuel-burning furnace for the purpose of increasing the thermal efficiency of the furnace. [e] (June 11) 2009 H1N1 influenza virus [r]: A contagious influenza A virus discovered in April 2009, commonly known as swine flu. [e] (June 4)

2009 H1N1 influenza virus [r]: A contagious influenza A virus discovered in April 2009, commonly known as swine flu. [e] (June 4) Gasoline [r]: A fuel for spark-ignited internal combustion engines derived from petroleum crude oil. [e] (21 May)

Gasoline [r]: A fuel for spark-ignited internal combustion engines derived from petroleum crude oil. [e] (21 May) John Brock [r]: Fictional British secret agent who starred in three 1960s thrillers by Desmond Skirrow. [e] (8 May)

John Brock [r]: Fictional British secret agent who starred in three 1960s thrillers by Desmond Skirrow. [e] (8 May) McGuffey Readers [r]: A set of highly influential school textbooks used in the 19th and early 20th centuries in the elementary grades in the United States. [e] (14 Apr)

McGuffey Readers [r]: A set of highly influential school textbooks used in the 19th and early 20th centuries in the elementary grades in the United States. [e] (14 Apr) Vector rotation [r]: Process of rotating one unit vector into a second unit vector. [e] (7 Apr)

Vector rotation [r]: Process of rotating one unit vector into a second unit vector. [e] (7 Apr) Leptin [r]: Hormone secreted by adipocytes that regulates appetite. [e] (31 Mar)

Leptin [r]: Hormone secreted by adipocytes that regulates appetite. [e] (31 Mar) Kansas v. Crane [r]: Add brief definition or description (24 Mar)

Kansas v. Crane [r]: Add brief definition or description (24 Mar) Punch card [r]: Add brief definition or description (17 Mar)

Punch card [r]: Add brief definition or description (17 Mar) Jass–Belote card games [r]: Add brief definition or description (10 Mar)

Jass–Belote card games [r]: Add brief definition or description (10 Mar) Leptotes (orchid) [r]: Add brief definition or description (3 Mar)

Leptotes (orchid) [r]: Add brief definition or description (3 Mar) Worm (computers) [r]: Add brief definition or description (24 Feb)

Worm (computers) [r]: Add brief definition or description (24 Feb) Joseph Black [r]: Add brief definition or description (11 Feb 2009)

Joseph Black [r]: Add brief definition or description (11 Feb 2009) Sympathetic magic [r]: Add brief definition or description (17 Jan 2009)

Sympathetic magic [r]: Add brief definition or description (17 Jan 2009) Dien Bien Phu [r]: Add brief definition or description (25 Dec)

Dien Bien Phu [r]: Add brief definition or description (25 Dec)- Blade Runner [r]: Add brief definition or description (25 Nov)

Piquet [r]: Add brief definition or description (18 Nov)

Piquet [r]: Add brief definition or description (18 Nov) Crash of 2008 [r]: Add brief definition or description (23 Oct)

Crash of 2008 [r]: Add brief definition or description (23 Oct) Information Management [r]: Add brief definition or description (31 Aug)

Information Management [r]: Add brief definition or description (31 Aug) Battle of Gettysburg [r]: Add brief definition or description (8 July)

Battle of Gettysburg [r]: Add brief definition or description (8 July) Drugs banned from the Olympics [r]: Add brief definition or description (1 July)

Drugs banned from the Olympics [r]: Add brief definition or description (1 July) Sea glass [r]: Add brief definition or description (24 June)

Sea glass [r]: Add brief definition or description (24 June) Dazed and Confused (Led Zeppelin song) [r]: Add brief definition or description (17 June)

Dazed and Confused (Led Zeppelin song) [r]: Add brief definition or description (17 June) Hirohito [r]: Add brief definition or description (10 June)

Hirohito [r]: Add brief definition or description (10 June) Henry Kissinger [r]: Add brief definition or description (3 June)

Henry Kissinger [r]: Add brief definition or description (3 June)- Palatalization [r]: Add brief definition or description (27 May)

Intelligence on the Korean War [r]: Add brief definition or description (20 May)

Intelligence on the Korean War [r]: Add brief definition or description (20 May) Trinity United Church of Christ, Chicago [r]: Add brief definition or description (13 May)

Trinity United Church of Christ, Chicago [r]: Add brief definition or description (13 May) BIOS [r]: Add brief definition or description (6 May)

BIOS [r]: Add brief definition or description (6 May) Miniature Fox Terrier [r]: Add brief definition or description (23 April)

Miniature Fox Terrier [r]: Add brief definition or description (23 April) Joseph II [r]: Add brief definition or description (15 Apr)

Joseph II [r]: Add brief definition or description (15 Apr) British and American English [r]: Add brief definition or description (7 Apr)

British and American English [r]: Add brief definition or description (7 Apr) Count Rumford [r]: Add brief definition or description (1 April)

Count Rumford [r]: Add brief definition or description (1 April) Whale meat [r]: Add brief definition or description (25 March)

Whale meat [r]: Add brief definition or description (25 March) Naval guns [r]: Add brief definition or description (18 March)

Naval guns [r]: Add brief definition or description (18 March) Sri Lanka [r]: Add brief definition or description (11 March)

Sri Lanka [r]: Add brief definition or description (11 March) Led Zeppelin [r]: Add brief definition or description (4 March)

Led Zeppelin [r]: Add brief definition or description (4 March) Martin Luther [r]: Add brief definition or description (20 February)

Martin Luther [r]: Add brief definition or description (20 February) Cosmology [r]: Add brief definition or description (4 February)

Cosmology [r]: Add brief definition or description (4 February) Ernest Rutherford [r]: Add brief definition or description(28 January)

Ernest Rutherford [r]: Add brief definition or description(28 January) Edinburgh [r]: Add brief definition or description (21 January)

Edinburgh [r]: Add brief definition or description (21 January) Russian Revolution of 1905 [r]: Add brief definition or description (8 January 2008)

Russian Revolution of 1905 [r]: Add brief definition or description (8 January 2008) Phosphorus [r]: Add brief definition or description (31 December)

Phosphorus [r]: Add brief definition or description (31 December) John Tyler [r]: Add brief definition or description (6 December)

John Tyler [r]: Add brief definition or description (6 December) Banana [r]: Add brief definition or description (22 November)

Banana [r]: Add brief definition or description (22 November) Augustin-Louis Cauchy [r]: Add brief definition or description (15 November)

Augustin-Louis Cauchy [r]: Add brief definition or description (15 November)- B-17 Flying Fortress (bomber) [r]: Add brief definition or description - 8 November 2007

Red Sea Urchin [r]: Add brief definition or description - 1 November 2007

Red Sea Urchin [r]: Add brief definition or description - 1 November 2007 Symphony [r]: Add brief definition or description - 25 October 2007

Symphony [r]: Add brief definition or description - 25 October 2007 Oxygen [r]: Add brief definition or description - 18 October 2007

Oxygen [r]: Add brief definition or description - 18 October 2007 Origins and architecture of the Taj Mahal [r]: Add brief definition or description - 11 October 2007

Origins and architecture of the Taj Mahal [r]: Add brief definition or description - 11 October 2007 Fossilization (palaeontology) [r]: Add brief definition or description - 4 October 2007

Fossilization (palaeontology) [r]: Add brief definition or description - 4 October 2007 Cradle of Humankind [r]: Add brief definition or description - 27 September 2007

Cradle of Humankind [r]: Add brief definition or description - 27 September 2007 John Adams [r]: Add brief definition or description - 20 September 2007

John Adams [r]: Add brief definition or description - 20 September 2007 Quakers [r]: Add brief definition or description - 13 September 2007

Quakers [r]: Add brief definition or description - 13 September 2007 Scarborough Castle [r]: Add brief definition or description - 6 September 2007

Scarborough Castle [r]: Add brief definition or description - 6 September 2007 Jane Addams [r]: Add brief definition or description - 30 August 2007

Jane Addams [r]: Add brief definition or description - 30 August 2007 Epidemiology [r]: Add brief definition or description - 23 August 2007

Epidemiology [r]: Add brief definition or description - 23 August 2007 Gay community [r]: Add brief definition or description - 16 August 2007

Gay community [r]: Add brief definition or description - 16 August 2007 Edward I [r]: Add brief definition or description - 9 August 2007

Edward I [r]: Add brief definition or description - 9 August 2007

Rules and Procedure

Rules

- The primary criterion of eligibility for a new draft is that it must have been ranked as a status 1 or 2 (developed or developing), as documented in the History of the article's Metadate template, no more than one month before the date of the next selection (currently every Thursday).

- Any Citizen may nominate a draft.

- No Citizen may have nominated more than one article listed under "current nominees" at a time.

- The article's nominator is indicated simply by the first name in the list of votes (see below).

- At least for now--while the project is still small--you may nominate and vote for drafts of which you are a main author.

- An article can be the New Draft of the Week only once. Nominated articles that have won this honor should be removed from the list and added to the list of previous winners.

- Comments on nominations should be made on the article's talk page.

- Any draft will be deleted when it is past its "last date eligible". Don't worry if this happens to your article; consider nominating it as the Article of the Week.

- If an editor believes that a nominee in his or her area of expertise is ineligible (perhaps due to obvious and embarrassing problems) he or she may remove the draft from consideration. The editor must indicate the reasons why he has done so on the nominated article's talk page.

Nomination

See above section "Add New Nominees Here".

Voting

- To vote, add your name and date in the Supporters column next to an article title, after other supporters for that article, by signing

<br />~~~~. (The date is necessary so that we can determine when the last vote was added.) Your vote is alloted a score of 1. - Add your name in the Specialist supporters column only if you are an editor who is an expert about the topic in question. Your vote is alloted a score of 1 for articles that you created and 2 for articles that you did not create.

- You may vote for as many articles as you wish, and each vote counts separately, but you can only nominate one at a time; see above. You could, theoretically, vote for every nominated article on the page, but this would be pointless.

Ranking

- The list of articles is sorted by number of votes first, then alphabetically.

- Admins should make sure that the votes are correctly tallied, but anyone may do this. Note that "Specialist Votes" are worth 3 points.

Updating

- Each Thursday, one of the admins listed below should move the winning article to the Current Winner section of this page, announce the winner on Citizendium-L and update the "previous winning drafts" section accordingly.

- The winning article will be the article at the top of the list (ie the one with the most votes).

- In the event of two or more having the same number of votes :

- The article with the most specialist supporters is used. Should this fail to produce a winner, the article appearing first by English alphabetical order is used.

- The remaining winning articles are guaranteed this position in the following weeks, again in alphabetical order. No further voting should take place on these, which remain at the top of the table with notices to that effect. Further nominations and voting take place to determine future winning articles for the following weeks.

- Winning articles may be named New Draft of the Week beyond their last eligible date if their circumstances are so described above.

- The article with the most specialist supporters is used. Should this fail to produce a winner, the article appearing first by English alphabetical order is used.

Administrators

The Administrators of this program are the same as the admins for CZ:Article of the Week.

References

See Also

- CZ:Article of the Week

- CZ:Markup tags for partial transclusion of selected text in an article

- CZ:Monthly Write-a-Thon