Psychiatry/Related Articles

- See also changes related to Psychiatry, or pages that link to Psychiatry or to this page or whose text contains "Psychiatry".

Parent topics

Text in this section is transcluded from the respective Citizendium entries and may change when these are edited.

This article is about the profession of medicine. For the substances known as "medicines", see medication or pharmacology. For practice in the allied health professions, (medicine, nursing, pharmacy etc.), see health science or health care. For more on the "art of medicine" and other approaches to healing and healing professions see healing arts.

Medicine is the oldest branch of health science. Medicine refers both to an area of knowledge, (human health, diseases and treatment), and to the applied practice of that knowledge. Medicine promotes health through the study of human biology, and the diagnosis and treatment of disease and injury. The practice of medicine is considered to be both an art and an applied science. The art is in the doctor-patient relationship that underlies the gathering of data, its interpretation, and the provision of therapy in clinical medicine. The practitioners of medicine, called physicians, hold doctorate degrees and have undergone a period of clinical apprenticeship called internship and residency training. Nearly all countries and legal jurisdictions have legal limitations on who may practice medicine. Medical doctors have established a standard protocol in the evaluation of patients that is uniform around the world and throughout the varying medical and surgical specialties: the patient history, physical examination and the analysis of laboratory results. The way that a patient's treatment is considered is also formulated in a manner that is generally accepted among all of the world's physicians. This involves establishing a diagnosis and prognosis for each presenting complaint, and has been used, by and large, since Aristotle's time in the Fourth Century BC. [1].The treatment plan advocated for any individual case largely depends on the specific diagnosis, and is also influenced by the prognosis. (need specific examples) []

Overview of specialties in medicineMedicine comprises hundreds of specialized branches. A basic distinction in medical specialties is between surgical and non-surgical areas, mainly because postgraduate training after medical school generally begins with either a medical or surgical internship, and one or the other is a pre-requisite for further training. Examples of the specialties and fields of medicine include cardiology, pulmonology, neurology, gastroenterology, endocrinology, hematology, genitourinary medicine, dermatology, critical care medicine and public health. Most of these specialities are further divided into sub-specialties. For example, the specialty of orthopedic surgery includes: sports medicine, pediatric orthopedic surgery and hand surgery. The word 'medicine' is also often used by medical professionals as shorthand for internal medicine, the non-surgical aspects of adult care. Physicians certified in Internal Medicine in the USA have completed a multi-year residency after graduating from medical school. Some train for an additional "Chief Resident" year before clinical practice. Other physicians trained in internal medicine subspecialize by training in a fellowship, such as gastroenterology, cardiology, or pulmonology. In some other countries, internal medicine is much more limited and specializations such as cardiology and pulmonology are not subfields of it, but full specializations on their own. History of medicineThe earliest type of medicine in most cultures was the use of plants (herbalism) and animal parts. This was usually in concert with 'magic' of various kinds in which: animism (the notion of inanimate objects having spirits); spiritualism (here meaning an appeal to gods or communion with ancestor spirits); shamanism (the vesting of an individual with mystic powers); and divination (the supposed obtaining of truth by magic means), played a major role. The practice of medicine developed gradually, and separately, in ancient Egypt, India, China, Greece, Persia and elsewhere. Medicine as it is practiced now developed largely in the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century in England (William Harvey, seventeenth century), Germany (Rudolf Virchow) and France (Jean-Martin Charcot, Claude Bernard and others). The new, "scientific" medicine (where results are testable and repeatable) replaced early Western traditions of medicine, based on herbalism, the Greek "four humours" and other pre-modern theories. The focal points of development of clinical medicine shifted to the UK and the USA by the early 1900s (Canadian-born) Sir William Osler, Harvey Cushing). Possibly the major change in medical thinking was the gradual rejection in the 1400's of what may be called the 'traditional authority' approach to science and medicine. This was the notion that because some prominent person in the past said something must be so, then that was the way it was, and anything one observed to the contrary was an anomaly (which was paralleled by a similar shift in European society in general - see Copernicus's rejection of Ptolemy's theories on astronomy). People like Vesalius led the way in improving upon or indeed rejecting the theories of great authorities from the past such as Galen, Hippocrates, and Avicenna/Ibn Sina, all of whose theories were in time discredited. Evidence-based medicine is a recent movement to establish the most effective algorithms of practice (ways of doing things) through the use of the scientific method and modern global information science by collating all the evidence and developing standard protocols which are then disseminated to doctors. One problem with this 'best practice' approach is that it could be seen to stifle novel approaches to treatment. Practice of medicineThe practice of medicine combines both science as the evidence base and art, in the application of this medical knowledge in combination with intuition and clinical judgement to determine the treatment plan for each patient. Central to medicine is the patient-doctor relationship, that begins when someone who is concerned about their health seeks a physician's help; the 'medical encounter'. As part of the medical encounter, the doctor needs to:

The medical encounter is documented in a medical record, which is a legal document in many jurisdictions.[2] Other health professionals similarly establish a relationship with a patient and might perform various interventions, e.g. nurses, radiographers and therapists. Health care delivery systemsMedicine is practiced within the medical system, which is a legal, credentialing and financing framework, established by a particular culture or government. The characteristics of the health care system have a very significant effect on the way that medical care is delivered. Financing has a great influence as it defines who pays the costs. The most significant divide in developed countries is between universal health care and market-based health care (as practiced in the USA). Universal health care might allow or ban a parallel private market. The latter is described as single-payor system. Transparency of information is another factor defining a delivery system. Access to information on conditions, treatments, quality and pricing greatly affects the choice by patients / consumers and therefore the incentives of medical professionals. While US health care system has come under fire for lack of openness, new legislation may encourage greater openness. There is a perceived tension between the need for transparency on the one hand and such issues as patient confidentiality and the possible exploitation of information for commercial gain on the other. Health care deliveryMedical care delivery is classified into primary, secondary and tertiary care. Primary care medical services are provided by physicians or other health professionals who has first contact with a patient seeking medical treatment or care. These occur in physician's office, clinics, nursing homes, schools, home visits and other places close to patients. About 90% of medical visits can be treated by the primary care provider. These include treatment of acute and chronic illnesses, preventive care and health education for all ages and both sex. Secondary care medical services are provided by medical specialists in their offices or clinics or at local community hospitals for a patient referred by a primary care provider who first diagnosed or treated the patient. Referrals are made for those patients who required the expertise or procedures performed by specialists. These include both ambulatory care and inpatient services, emergency rooms, intensive care medicine, surgery services, physical therapy, labor and delivery, endoscopy units, diagnostic laboratory and medical imaging services, hospice centers, etc. Some primary care providers may also take care of hospitalized patients and deliver babies in a secondary care setting. Tertiary care medical services are provided by specialist hospitals or regional centers equipped with diagnostic and treatment facilities not generally available at local hospitals. These include trauma centers, burn treatment centers, advanced neonatology unit services, organ transplants, high-risk pregnancy, radiation oncology, etc. Modern medical care also depends on information - still delivered in many health care settings on paper records, but increasingly nowadays by electronic means. Doctor-patient relationshipThe doctor-patient relationship and interaction is a central process in the practice of medicine. There are many perspectives from which to understand and describe it. An idealized physician's perspective, such as is taught in medical school, sees the core aspects of the process as the physician learning the patient's symptoms, concerns and values; in response the physician examines the patient, interprets the symptoms, and formulates a diagnosis to explain the symptoms and their cause to the patient and to propose a treatment. The job of a doctor is essentially to be a human biologist: that is, to know the human frame and situation in terms of normality. Once the doctor knows what is normal and can measure the patient against those norms the doctor can then determine the particular departure from the normal and the degree of departure. This is called the diagnosis. The four great cornerstones of diagnostic medicine are anatomy (structure: what is there), physiology (how the structure/s work), pathology (what goes wrong with the anatomy and physiology) and psychology (mind and behaviour). In addition, the doctor should consider the patient in their 'well' context rather than simply as a walking medical condition. This means the socio-political context of the patient (family, work, stress, beliefs) should be assessed as it often offers vital clues to the patient's condition and further management. In more detail, the patient presents a set of complaints (the symptoms) to the doctor, who then obtains further information about the patient's symptoms, previous state of health, living conditions, and so forth. The physician then makes a review of systems (ROS) or systems enquiry, which is a set of ordered questions about each major body system in order: general (such as weight loss), endocrine, cardio-respiratory, etc. Next comes the actual physical examination; the findings are recorded, leading to a list of possible diagnoses. These will be in order of probability. The next task is to enlist the patient's agreement to a management plan, which will include treatment as well as plans for follow-up. Importantly, during this process the doctor educates the patient about the causes, progression, outcomes, and possible treatments of his ailments, as well as often providing advice for maintaining health. This teaching relationship is the basis of calling the physician doctor, which originally meant "teacher" in Latin. The patient-doctor relationship is additionally complicated by the patient's suffering (patient derives from the Latin patior, "suffer") and limited ability to relieve it on his/her own. The doctor's expertise comes from his knowledge of what is healthy and normal contrasted with knowledge and experience of other people who have suffered similar symptoms (unhealthy and abnormal), and the proven ability to relieve it with medicines (pharmacology) or other therapies about which the patient may initially have little knowledge. The doctor-patient relationship can be analyzed from the perspective of ethical concerns, in terms of how well the goals of non-maleficence, beneficence, autonomy, and justice are achieved. Many other values and ethical issues can be added to these. In different societies, periods, and cultures, different values may be assigned different priorities. For example, in the last 30 years medical care in the Western World has increasingly emphasized patient autonomy in decision making. The relationship and process can also be analyzed in terms of social power relationships (e.g., by Michel Foucault), or economic transactions. Physicians have been accorded gradually higher status and respect over the last century, and they have been entrusted with control of access to prescription medicines as a public health measure. This represents a concentration of power and carries both advantages and disadvantages to particular kinds of patients with particular kinds of conditions. A further twist has occurred in the last 25 years as costs of medical care have risen, and a third party (an insurance company or government agency) now often insists upon a share of decision-making power for a variety of reasons, reducing freedom of choice of both doctors and patients in many ways. The quality of the patient-doctor relationship is important to both parties. The better the relationship in terms of mutual respect, knowledge, trust, shared values and perspectives about disease and life, and time available, the better will be the amount and quality of information about the patient's disease transferred in both directions, enhancing accuracy of diagnosis and increasing the patient's knowledge about the disease. Where such a relationship is poor the doctor's ability to make a full assessment is compromised and the patient is more likely to distrust the diagnosis and proposed treatment. In these circumstances and also in cases where there is genuine divergence of medical opinions, a second opinion from another doctor may be sought. In some settings, e.g. the hospital ward, the patient-doctor relationship is much more complex, and many other people are involved when somebody is ill: relatives, neighbors, rescue specialists, nurses, technical personnel, social workers and others. Clinical skillsA complete medical evaluation includes a medical history, a systems enquiry, a physical examination, appropriate laboratory or imaging studies, analysis of data and medical decision making to obtain diagnoses, and a treatment plan.[3] The components of the medical history are:

The physical examination is the examination of the patient looking for signs of disease ('Symptoms' are what the patient volunteers, 'signs' are what the doctor detects by examination). The doctor uses his senses of sight, hearing, touch, and sometimes smell (taste has been made redundant by the availability of modern lab tests). Four chief methods are used: inspection, palpation (feel), percussion (tap to determine resonance characteristics), and auscultation (listen); smelling may be useful (e.g. infection, uremia, diabetic ketoacidosis). The clinical examination involves study of:

Laboratory and imaging studies results might be obtained, if necessary. The medical decision-making (MDM) process involves analysis and synthesis of all the above data to come up with a list of possible diagnoses (the differential diagnoses), along with an idea of what needs to be done to obtain a definitive diagnosis that would explain the patient's problem. The treatment plan might include ordering additional laboratory tests and studies, starting therapy, referral to a specialist, or watchful observation. Follow-up may be advised. This process is used by primary care providers as well as specialists. It may take only a few minutes if the problem is simple and straightforward, but it may take weeks in a patient who has been hospitalized with unusual symptoms or multi-system problems, with involvement of several specialists. On subsequent visits, the process may be repeated in an abbreviated manner to obtain any new history, symptoms, physical findings, and lab or imaging results or specialist consultations. Medical specialties

Medical educationMedical education is education related to the practice of being a medical practitioner, either the initial training to become a doctor or further training thereafter. Medical education and training varies considerably across the world, however typically involves entry level education at a university medical school, followed by a period of supervised practise (internship and/or residency) and possibly postgraduate vocational training. Continuing medical education is a requirement of many regulatory authorities. Various teaching methodologies have been utilised in medical education, which is an active area of educational research. Legal restrictionsIn most countries, it is a legal requirement for medical doctors to be licensed or registered. In general, this entails a medical degree from a university and accreditation by a medical board or an equivalent national organization, which may ask the applicant to pass exams. This restricts the considerable legal authority of the medical profession to doctors who are trained and qualified by national standards. It is also intended as an assurance to patients and as a safeguard against charlatans that practice inadequate medicine for personal gain. While the laws generally require medical doctors to be trained in "evidence based", Western, or Hippocratic Medicine, they are not intended to discourage different paradigms of health and healing, such as alternative medicine or faith healing. CriticismCriticism of medicine has a long history. In the Middle Ages, some people did not consider it a profession suitable for Christians, as disease was often considered God sent. God was considered to be the 'divine physician' who sent illness or healing depending on his will. However many monastic orders, particularly the Benedictines, considered the care of the sick as their chief work of mercy. Barber-surgeons (they had the sharpest knives) generally had a bad reputation that was not to improve until the development of academic surgery as a speciality of medicine, rather than an accessory field. Through the course of the twentieth century, doctors focused increasingly on the technology that was enabling them to make dramatic improvements in patients' health. The ensuing development of a more mechanistic, detached practice, with the perception of an attendant loss of patient-focused care, known as the medical model of health, led to further criticisms. This issue started to reach collective professional consciousness in the 1970s and the profession had begun to respond by the 1980s and 1990s. Perhaps the most devastating criticism of modern medicine came from Ivan Illich. In his 1976 work Medical Nemesis, Illich stated that modern medicine only medicalises disease and causes loss of health and wellness, while generally failing to restore health by eliminating disease. This medicalisation of disease forces the human to become a lifelong patient.[4]Other less radical philosophers have voiced similar views, but none were as virulent as Illich. Another example can be found in Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology by Neil Postman, 1992, which criticises overreliance on technological means in medicine.

References

|

Subtopics

Text in this section is transcluded from the respective Citizendium entries and may change when these are edited.

Schizophrenia1 is a mental disorder characterized by patterns of disordered thought, language, motor, and social function. [1] Males typically develop symptoms in their late teens and early 20s, while females exhibit a later onset, usually in the mid-20s to early 30s. More variations in onset and symptomology may exist across gender, age, and culture, although these factors have not been clearly deliniated. During the acute stage of schizophrenia, the primary symptom is a break from reality in which individuals experience thoughts, perceptions and beliefs that are considered strange and bizarre by the general population. Despite common and popular perception, the multiple personalities and dissociative characteristics associated with dissociative identity disorder are in no way related to schizophrenia, and the two are completely separate disorders. The specific cause of schizophrenia is largely unknown, although several neurotransmitters and brain structures are hypothesized to play a role in the disorder.

The word schizophrenia was introduced in 1908 by psychologist Eugen Bleuler in his work Dementia Praecox oder Gruppe der Schizophrenien (Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias). He used the word schizophrenia to emphasize the split (schiz) of mental processes within the mind. (Read more...) | ||||||||||||

Autism (pronounced IPA /'ɔtizm/) is classified by the World Health Organization and American Psychological Association as a developmental disability that results from a disorder of the human central nervous system. It is diagnosed using specific criteria for impairments to social interaction, communication, interests, imagination and activities.[3] Autism manifests before the age of three years, according to the World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10)[4]. Autistic children are marked by delays in their "social interaction, language as used in social communication, or symbolic or imaginative play" (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders).[5] Autism and the other four pervasive developmental disorders (PDD) are considered to be neurodevelopmental disorders. They are diagnosed on the basis of a triad of behavioral impairments or dysfunctions: 1. impaired social interaction, 2. impaired communication and 3. restricted and repetitive interests and activities.[6] From a physiological standpoint, autism is often less than obvious, in that outward appearance may not indicate a disorder. Diagnosis typically comes from a complete patient history and physical and neurological evaluation. The incidence of diagnosed autism has increased since the 1990s.[7] Reasons offered for this phenomenon include better diagnosis, wider public awareness of the condition, regional variations in diagnostic criteria, or an actual increase in the occurrence of ASD (autism spectrum disorders). The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimate the prevalence of autism spectrum disorders to be about one in every 150 children.[8][9] In 2005, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) stated the "best conservative estimate" as 1 in 1000.[10] In 2006, NIMH estimated that the incidence was 2-6 in every 1000[11] There are numerous theories as to the specific causes of autism, but they are as yet unproven (see section on "Causes" below). Proposed factors include genetic influence, anatomical variations (e.g. head circumference), abnormal blood vessel function and oxidative stress. Their significance as well as implications for treatment remain speculative. TerminologyWhen referring to someone who is diagnosed with autism, the term "autistic" is often used. Alternatively, many prefer to use the person-first terminology, i.e. "person with autism" or "person who experiences autism." However, it has been noted that members of the autistic community generally prefer "autistic person" for reasons that are fairly controversial.[12] This article uses both terminologies. HistoryThe word "autism" was first used in the English language by Swiss psychiatrist Eugene Bleuler in a 1912 issue of the American Journal of Insanity. It comes from the Greek word for "self," αυτος (autos).[13] Autism was actually confused with schizophrenia during the early stages of observation.[14] Bleuler used the term to describe schizophrenics' seeming difficulty in connecting with other people.[15] However, the medical classification of autism as a separate disorder or disease did not occur until 1943 when psychiatrist Dr. Leo Kanner of the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland reported on 11 child patients with striking behavioral similarities and introduced the label "early infantile autism."[16] He suggested the term "autism" to describe the fact that the children seemed to lack interest in other people, emphasizing "autistic aloneness" and "insistence on sameness". Kanner's first paper on the subject was published in the journal The Nervous Child (no longer in publication),[17] and almost every characteristic he originally described is still regarded as typical of the autistic spectrum of disorders diagnostic triad of behavioral impairments or dysfunctions: 1. impaired social interaction, 2. impaired communication and 3. restricted and repetitive interests and activities.[18].[19] Leo Kanner's contemporary in Austria, Dr. Hans Asperger, made similar observations, although his name has since become attached to a different form of autism known as Asperger's Syndrome. Widespread recognition of Asperger's work was delayed by World War II in Germany. His seminal paper was not actually translated into English for almost 50 years and the majority of his work was not widely read until 1997.[20] Autism and Asperger's Syndrome are today listed in the DSM-IV-TR as two of the five pervasive developmental disorders (PDD), which also include Childhood disintegrative disorder,[21][22] Rett syndrome[23] and Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (or atypical autism). Health care providers also refer to autism spectrum disorders (ASD) which includes only three of those listed in PDD: Autistic disorder, Asperger syndrome, Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified.[24] All of these conditions are characterized by varying degrees of deficiencies in communication skil]s and social interactions, along with restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped patterns of human behavior. CharacteristicsOn the surface, individuals who have autism are physically indistinguishable from those without. Some studies show that autistic children tend to have larger head circumferences[25][26] but the significance in the disorder is unclear. Sometimes autism co-occurs with other disorders, and in those cases outward differences may be apparent. Individuals diagnosed with autism can vary greatly in skills and behaviors, and their response to sensory input shows marked differences in a number of ways from that of other people. Certain stimuli, such as sounds, lights, and touch, will often affect someone with autism differently than someone without, and the degree to which the sensory system is affected can vary greatly from one individual to another.[27] Key behaviorsAutistic children may display unusual behaviors or fail to display expected behaviors. Normal behaviors may develop at the appropriate age and then disappear or, conversely, are delayed and develop quite some time after normal occurrence. In assessing developmental delays, different physicians may not always arrive at the same conclusions. Much of this difference between diagnosis is due to the disputed criteria for autism.[28] Disagreement on deciding how a child should normally behave also makes it difficult to construct objective tests of child behavior. Essentially, the diagnosis of autism must meet specific criteria but there are also many characteristics that are idiosyncratic. Thus, autism is not a "one size fits all" label. As a result, the spectrum disorder encompasses a very wide range of behaviors and symptoms. Some behaviors cited by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (listed below) may simply mean a normal delay in one or more areas of development, while others are more typical of ASDs—Autistic Spectrum Disorders.[24] The list below is not all-inclusive, and generally applies to children and not adults. Furthermore, while some of these behaviors might be seen in a person with autism, others may be absent.[24] Noted behaviours

Autism and blindnessThe characteristics of a person with both an Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and a severe visual impairment (VI) may vary from a person with just ASD or just VI.[29] Historically, many behaviors of blind children were seen as "autistic-like" but were attributed to their blindness rather than pursuing possibilities of autism.[30] Developmental trajectories of children with ASD-VI are often very similar as those followed by children with typical autism, but the child with ASD-VI will have particularly unusual responses to sensory information. The person may be overly sensitive to touch or sound, or be less responsive to pain. Typically, touch, smell, and sound are affected the most dramatically.[31] Repetitive behaviorsAlthough people with autism usually appear physically normal, unusual repetitive motions, known as self-stimulation or "stimming," may set them apart. These behaviors might be extreme or subtle. Some children and older individuals spend a lot of time repeatedly flapping their arms or wiggling their toes, others suddenly freeze in position. Some spend hours arranging objects in a certain way rather than engaging in pretend play as a typical child might, and becoming agitated if they are re-arranged or moved. Repetitive behaviors can also extend into the spoken word; perseveration of a single word or phrase can also become a part of the child's daily routine. Some may repeat words from movies and watch certain bits over and over again.[32][33] Autistic children may demand consistency in their environment. A slight change in the timing, format or route of a routine or trip can be extremely disturbing to them. Autistics sometimes have persistent, intense preoccupations. For example, the child might be obsessed with learning all about computers, television programs, lighthouses or virtually any other topic.[24]

Types of autismAutism presents in a wide degree, from those who are socially dysfunctional and apparently mentally disabled to those whose symptoms are mild or remedied enough to appear unexceptional ("normal") to others. Although this is controversial, autistic individuals are often divided into those with an IQ less than 80 (referred to as having "low-functioning autism" or LFA), and those with an IQ over 80 (referred to as having "high-functioning autism" (HFA).[34][35][36]) Low and high functioning are more generally applied to how well an individual can accomplish activities of daily living, rather than to IQ. The terms low and high functioning are controversial and not all autistics accept these labels. Additionally, a review of the literature in 2005 questioned the validity of IQ testing of autistic people, noting the frequency of poor methodology in numerous studies that assumed or failed to demonstrate impaired cognitive functioning.[37][38] This discrepancy can lead to confusion among service providers who equate IQ with functioning and may refuse to serve high-IQ autistic people who are severely compromised in their ability to perform daily living tasks, or may fail to recognize the intellectual potential of many autistic people who are considered LFA. For example, some professionals refuse to recognize autistics who can speak or write as being autistic at all, because they still think of autism as a communication disorder so severe that no speech or writing is possible. As a consequence, many "high-functioning" autistic persons, and autistic people with relatively high IQ, are under-diagnosed, thus making the claim that "autism implies retardation" self-fulfilling. The number of people diagnosed with LFA is not rising quite as sharply as HFA, indicating that at least part of the explanation for the apparent rise is probably better diagnostics. Many also think that ASD's are being over diagnosed: (1) because the growth in the number and complexity of symptoms associated with autism has increased the chances professionals will erroneously diagnose autism and (2) because the growth in services and therapies for autism has increased the number who falsely qualify for those often free services and therapies. Asperger's Syndrome and Classic Autism DisorderIn the current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR), the most significant difference between Autistic Disorder and Asperger's syndrome is that a diagnosis of the former includes the observation of "delays or abnormal functioning in at least one of the following areas, with onset prior to age 3 years: (1) social interaction, (2) language as used in social communication, or (3) symbolic or imaginative play",[39] while a diagnosis of Asperger's syndrome observes "no clinically significant delay" in the latter two of these areas.[40] While the DSM-IV does not include level of intellectual functioning in the diagnosis, the fact that those with Asperger's syndrome tend to perform better than those with classic autism has produced a popular conception that Asperger's syndrome is synonymous with "higher-functioning autism", or that it is a lesser disorder than autism. The extent to which someone with higher functioning autism or Asperger's syndrome may excel is theoretically quite high. For example, Henry Cavendish, one of history's foremost scientists, may have been autistic. George Wilson, a notable chemist and physician, wrote a book about Cavendish entitled, "The Life of the Honourable Henry Cavendish", published in 1851. From Wilson's detailed description it seems that while Cavendish may have exhibited many classic signs of autism, he nevertheless had an extraordinary mind.[41] Autism as a spectrum disorderAnother view of these disorders is that they are on a continuum known as autistic spectrum disorders. Autism spectrum disorder is an increasingly popular term that refers to a broad definition of autism including the classic form of the disorder as well as closely related conditions such as PDD-NOS (Pervasive Developmental Disorders-Not Otherwise Specified) and Asperger's syndrome. Although the classic form of autism can be easily distinguished from other forms of autism spectrum disorder, the terms are often used interchangeably. A related continuum, Sensory Integration Dysfunction, involves how well humans integrate the information they receive from their senses. Autism, Asperger's syndrome, and Sensory Integration Dysfunction are all closely related and overlap. Some people believe that there might be two manifestations of classical autism, regressive autism and early infantile autism. Early infantile autism is present at birth while regressive autism begins before the age of 3 and often around 18 months. Although this causes some controversy over when the neurological differences involved in autism truly begin, some speculate that an environmental influence or toxin triggers the disorder. This triggering could occur during gestation due to a toxin that enters the mother's body and is transferred to the fetus. The triggering could also occur after birth during the crucial early nervous system development of the child. A paper published in 2006 concerning the behavioral, cognitive, and genetic bases of autism argues that autism should perhaps not be seen as a single disorder, but rather as a set of distinct symptoms (social difficulties, communicative difficulties and repetitive behaviors) that have their own distinct causes.[42] An implication of this would be that a search for a "cure" for autism is unlikely to succeed if it is not examined as separate, albeit overlapping and commonly co-occurring, disorders. EpidemiologyGender differences The ratio of incidence between males and females (as demonstrated in the scientific literature) is ambiguous. Studies have found much higher prevalence in males at the high-functioning end of the spectrum, while the ratios appear to be closer to 1:1 at the low-functioning end.[43] In addition, a study published in 2006 suggested that males over 40 are more likely than younger males to parent a child with autism, and that the ratio of autism incidence in males and females is closer to 1:1 with older fathers.[44][45] Reported increase with time There was a worldwide increase in reported cases of autism over the decade leading up to 2006. There are several theories about this apparent sudden increase. Many epidemiologists argue that the rise in the incidence of autism in the United States is largely attributable to a broadening of the diagnostic concept, earlier diagnosis (thereby accounting for those cases which are actually diagnosed as early as one year of age)[46] reclassifications, public awareness, and the incentive to receive federally mandated services.[47] However, some authors indicate that the existence of an as yet unidentified contributing environmental risk factor cannot be ruled out.[48] A widely-cited pilot study conducted in California by the UC Davis M.I.N.D. Institute (17 October, 2002), reported that the increase in autism in California is real, even after accounting for changes to diagnostic criteria.[49] The question of whether the rise in incidence is real or an artifact of improved diagnosis and a broader concept of autism remains controversial. Dr. Chris Johnson, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio and co-chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Autism Expert Panel, sums up the state of the issue by saying, "There is a chance we're seeing a true rise, but right now I do not think anybody can answer that question for sure." [50] Treatment U.S. President George W. Bush signing a piece of legislation aimed to combat autism The efficacy of treating autism is disputed. There is a broad array of proposed autism therapies with various goals, e.g. improving health and well-being, emotional problems, difficulties with communication and learning, and sensory problems for people with autism, but the effectiveness of these approaches is not clear. Antipsychotics are used to manage disruptive and violent behavior, such as irritability, tantrums and violence. Risperidone (trade name Risperdal) is the only anti-psychotic agent currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat children and adolescents with autism.[51] Risperidone benefited patients in a randomized controlled trial.[52] Physiology and neurologyAutism appears to involve a greater amount of the brain than previously thought.[53] A study of 112 children (56 with autism and 56 without), published in the Journal of Child Neuropsychology, found those with autism to have more problems with complex tasks, such as tying their shoelaces or writing, which suggests that many areas of the brain are involved.[54] Children with autism performed simple tasks as well as or better than those without. In tests of visual and spatial skills, autistic children did well at finding small objects in complex pictures (e.g., finding the character Waldo in "Where's Waldo" pictures). However, they found it difficult to tell the difference between similar-looking people. Children with autism tended to do well in spelling and grammar, but found it much more difficult to understand complex speech, such as idioms or similes when the meaning of the phrase is figurative. They would, for example, not understand that "He kicked the bucket" meant someone had died, or were likely to actually hop if told to "hop to it". The research from this perspective has a number of implications:

A possible explanation for the characteristics of the syndrome is a variation in the way the brain itself reacts to sensory input and how parts of the brain then handle the information. An electroencephalographic (EEG) study of 36 adults (half of whom had autism) at Washington University in St. Louis found that adults with autism show differences in the manner in which neural activity is coordinated. The implication seems to be that there is poor internal communication between different areas of the brain. (Electroencephalographs, or EEGs, measure the activity of brain cells.) The Wash. U. study indicated that there were abnormal patterns in the way the brain cells were connected in the temporal lobe of the brain. (The temporal lobe deals with language.) These abnormal patterns would seem to indicate inefficient and inconsistent communication inside the brain of autistic people.[55] Studies in neuropathology indicate abnormalities in the amygdala, hippocampus, septum, mamillary bodies, limbic system,and the cerebellum. [56][57]

Research has not yet established exactly what is specific to autism and what may be seen in other disorders however.[56] Individuals with autism are also far more likely to develop epilepsy than would otherwise be expected (estimated 10-30% incidence). [58] Mirror neuronsA theory featuring mirror neurons[59][60] states that autism may involve a dysfunction of specialized neurons in the brain that should activate when observing other people. In typically-developing people, these mirror neurons are thought to perhaps play a major part in social learning and general comprehension of the actions of others. CausesThe causes and etiology of autism are uncertain. Possible genetic and environmental causes are a common focus in published literature. Since autistic individuals are all somewhat different from one another, multiple "causes" have been proposed that interact with each other in subtle and complex ways, and thus give slightly differing outcomes in each individual. Research claims also link autism with abnormal blood vessel function, and oxidative stress. [61] Genetic componentExtent of genetic origins of autism spectrum disorders: Genetic influence comprises a significant aspect of research in the causes of autism.[62] More than one hundred different genes have been implicated in the causes of autism spectrum disorders (ASD). One type of genetic origin are “glitches” or small changes in DNA that are not genetic mutations, per se, but copy number variations (CNVs) which are extra copies or missing stretches of DNA. (In one case study a child with Asperger’s Syndrome was found to be missing a chain of 27 genes.) The extent of the possible genetic origins indicate that the abilities in social interaction and behavior, social and physical composure and impulse control are scattered throughout the human genome, implying that small genetic alterations, copies or deletions anywhere can have broad effects[63] A large database showing theoretical links between autism and genetic loci summarises research indicating that the genetic influence may extend to every human chromosome.[64] It has been observed in one twin-study in Britain that there was about a 60% concordance rate for autism in monozygotic (identical) twins,[65] while dizygotic (non-identical) twins and other siblings comparatively exhibited about 4% concordance rates.[66] Some research posits that the chances that an identical twin of an autistic person will also be autistic are 85-90%.[67] The increased probabilities of siblings having autism has been calculated at about 35-fold more than normal.[68] Generational links, or familial heritability may, however, be less prevalent than some research to date implies. Spontaneous changes in DNA are much more common than is usual in other diseases with a genetic component. The sporadic form of the disease accounts for about 90% of affected individuals. [63] Comorbidity: Accompanying impairments are also a common feature of autism. Some people with autism also have gastrointestinal, immunological or neurological symptoms in addition to behavioral impairments. These associated complexes have also lead to the search for specific genetic connections and helped to focus on reasonable genetic implications.[68] Since genes provide the information for processes and structure at the level of the cell and its components during the growth and development of a human as well as maintenance during life, gene mutations (altered versions) and deletions (complete absence of genetic material) and possibly extra copies of genes would mean that the causes of autism begin very early. If a mutated gene fails to perform properly, then cells, proteins, enzymes and other crucial aspects of normal function may be significantly altered and operate incorrectly. Deletions could mean the complete absence of a sequence of events due to missing proteins or cell components for example. These genetic alterations and deletions will simply bring about a changed structure or process which effects a great many other needed structures and processes. Deletions and mutationsGene deletion: Deleted genes may be an influence or cause of autism. [62] By locating missing genetic material, specific DNA involved in non-autistic behavior (autism susceptibility alleles) may be identified. Another significant aspect of this research is that deleted genetic material indicates that autism may be established during meiosis (error-prone meiosis model) and this theoretically places the genesis of autism at the very beginning of life. One very important question in this line of research is whether or not specific gene deletions cause or are a consequence of autism-susceptibility loci located elsewhere in the chromosomes. Gene mutations: A mutation may mean a gene does not function at all or does not function in the normal way. Since genes direct how the body grows and develops, mutations, like deletions, will effect a person at the most basic levels. Mutation and deletion effects have been delineated in numerous research publications.[69][70][71][72][73] Gene interaction: Interactions between genetic material may also complicate the causes leading to multiple genetic origins of autism. [70][74] In a cascade like effect, when a gene loci is altered or omitted, others are effected due to change in interaction between genes and/or their functions. Correlated characteristics: Effects that accompany deletions and mutations include global developmental delay, mild to severe delay of speech, social communication disorders and cognitive abilities, autistic like behaviour, high tolerance of pain, and repetitive mannerisms (e.g. chewing or mouthing). [74] Practical applications for research: Though not present in all individuals with autism, these mutations and deletions hold potential to point the way to other genetic factors involved in spectrum disorders. [75] This type of research may lead to the development of a test that would confirm the autism diagnosis in children exhibiting symptoms and identify families who carry genetic defects that could be inherited by their children. The research also advances basic understanding in the genetic architecture of the genome of autistic individuals and helps in focusing future research. Environmental componentsAnother important aspect of research in ASDs is environmental effects and the incidence of autism. Environmental factors such as mercury and radiation have been proposed as possible causes of ASD. According to this theoretical explanation, during the lifetime of a person, gene mutations and deletions may be environmentally triggered or exacerbated. Conversely, it may also be that environment will not be a factor and nothing will change the autism characteristics: the nature of the sporadic CNVs does not imply the presence of an environmental agent. [63] Mercury Current recommandations about fish intake in children and pregnant women are determined in function of the risk of mercury exposure, despite the fact that fish, in itself, provides many nutrients required for proper brain function. Mercury, in the form of methylmercury (its organic form, as opposed to pure mercury), at levels encountered in foetuses of mothers eating fish regularly, is associated with mental impairments consistent with autism. Methylmercury impairs the regulation of the most important excitatory neurotransmitter, glutamate, by impairing the ability of glial cells to "wash it" from the space between neurons, thus causing a form of neuronal degeneration called excitotoxicity.[76] In addition, researchers from the University of Texas correlated the amount of mercury released in different school districts of Texas to the number of cases of autism: each 1000 lb of environmentally released mercury appeared to increase by 43 % the rates of autism.[77] Other pervasive developmental disordersAutism and Asperger's syndrome are two of the five pervasive developmental disorders (PDDs); the three others are Rett syndrome, Childhood disintegrative disorder, and Pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified. Some of these are related to autism, while some of them are entirely separate conditions. Notes

| ||||||||||||

Alzheimer's disease is also known as Alzheimer disease, Alzheimer's and simply AD. Alzheimer's is the most common cause of dementia, afflicting at least 44 million people worldwide, as of 2016. Alzheimer's is a terminal disease for which there is currently no known cure. It is most commonly found in people over 65 years old, although a less-common form called Familial Alzheimer's disease, or "early-onset Alzheimer's", also occurs, affecting about 1%—5% of the total of Alzheimer's sufferers.[1] Typically, the disease begins many years before it is diagnosed. In its early stages, short-term memory loss is the most common symptom, which is often initially thought by the sufferer to be caused by other factors, such as aging or stress.[2] Later symptoms of the disease include confusion, anger, mood swings, language breakdown, long-term memory loss, and the general "withdrawal" of the sufferer as his or her senses decline.[2][3] Gradually the sufferer will lose minor, and then major bodily functions, until death finally occurs.[4] Survival after diagnosis has been estimated to be between 5 and 20 years.[5][6] SymptomsCommon symptoms of dementia include: A decline in memory Changes in thinking skills Poor judgment and reasoning Decreased focus and attention Decreased language ability Negative changes in behavior Although the symptoms are common, they are typically experienced in unique ways.[7] "Stages" are commonly referred to by professionals to describe the progressive nature of Alzheimer's (typically "early", "mid" and "late onset") but the symptoms can cross over these "boundaries" for many sufferers. DiagnosisThe symptoms of Alzheimer's disease are generally reported to a doctor or physician when memory-loss (or symptoms surrounding memory loss) begins to pose a serious concern. When Alzheimer's disease is suspected, diagnosis is typically confirmed by a behavioural assessment, and some form of cognitive test. Often this is followed by a brain scan, such as a PET scan.[8] CriteriaThere are three sets of criteria for the clinical diagnoses of the spectrum of Alzheimer's disease: the 2013 fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5); the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association (NIA-AA) definition as revised in 2011; and the International Working Group criteria as revised in 2010. Three periods, which can span decades, define the progression of Alzheimer's disease from the preclinical phase, to mild cognitive impairment (MCI), followed by Alzheimer's disease dementia. Eight intellectual domains are most commonly impaired in AD: memory, language, perceptual skills, attention, motor skills, orientation, problem solving, and executive functional abilities, as listed in the fourth text revision of the DSM (DSM-IV-TR). The DSM-5 defines criteria for probable or possible Alzheimer's for both major and mild neurocognitive disorder. Major or mild neurocognitive disorder must be present along with at least one cognitive deficit for a diagnosis of either probable or possible AD. Laboratory testsApolipoprotein E4Although apolipoprotein E4 is an important susceptibility gene for Alzheimer's disease][9], its sensitivity and specificity are insufficient (65 and 68 percent, respectively) to be used as a diagnostic test.[10] However, the level of apolipoprotein E4 in cerebrospinal fluid may be predictive.[11] Amyloid-beta proteinAmyloid-beta protein may be elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid of some patients.[11] AutopsyCompletely reliable confirmation of a Alzheimer's diagnosis has traditionally only been possible upon the death of the patient. The brain tissue will be examined by a pathologist, and there are two unique lesions that are unmistakable signs of Alzheimer's that will give definite confirmation. Cause/etiologyThe etiology of Alzheimer's disease is incompletely understood. Alzheimer's disease is associated with senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the brain.[12] The incorrect folding of proteins leads to the formation of amyloid plaques. The prion protein (PrPC) may be the cellular receptor for amyloid-beta oligomer.[13] Current research aims to determine if such plaques are the result of, or the cause of, Alzheimer's disease. Regarding biomarkers, one study found that "a reduction in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Aβ42 level denotes a pathophysiological process that significantly departs from normality (i.e., becomes dynamic) early, whereas the CSF total tau level and the adjusted hippocampal volume are biomarkers of downstream pathophysiological processes". [14] Although there is a genetic susceptibility in a small percentage of people, Alzheimer's is not considered a genetic illness. The greatest risk factor for developing Alzheimer's is age, as the percentage of people developing it dramatically increases after age 65 and beyond. Major environmental/lifestyle risk factors include a diet high in saturated fats that are typical of the standard western diet, smoking, and long-term exposure to environmental toxins such as aluminium. Research is ongoing. Alzheimer's appears to be a disease of the modern world, especially developed societies. Prior to the early 20th century, this dementia was completely unknown to science and was never described in elder members of traditional societies. Individuals with the genetic disease Down syndrome (trisomy 21) are at much higher risk for developing Alzheimer's in their middle age. According to the National Down Syndrome Society, about 30% of people with Down syndrome who are in their 50s, and about 50% of those in their 60s, have Alzheimer’s disease. The lifetime risk is over 90%. [15] EpidemiologyIn the United States in 2020, Alzheimer's dementia prevalence was estimated to be 5% for those in the 60–74 age group, with the rate increasing to 14% in the 74–84 group and to 35% in those greater than 85.[16] Advancing age is a primary risk factor for the disease and incidence rates are not equal for all ages: every 5 years after the age of 65, the risk of acquiring the disease approximately doubles, in developed societies such as Spain and Italy. TreatmentAs of 2024, no treatment has been found to stop progression or completely reverse the disease, but some treatments do slow the progression. Many preventive measures have been suggested for Alzheimer's disease, but their values are uncertain: mental stimulation, exercise, and a Mediterranean style diet are usually recommended, both as possible prevention and as a sensible way of managing the disease.[17] MedicationsAs of 2023, available medications offer relatively small symptomatic benefit for some patients but generally do not slow disease progression. Newer monoclonal antibody treatments against beta-amyloid protein, for example, the drug Leqembi, have been approved in the United States, but they only slightly reduce the rate of disease progression and have significant side effects, including brain bleeding and in rare cases, death. These drugs cost over $20,000 a year, which could be prohibitively expensive for many patients. Randomized controlled trials showed either small or absent benefit from acetylcholinesterase inhibitors[18] such as donepezil.[19][20][21] The N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonist memantine has shown some effectiveness[22] but does not add benefit to donepezil .[21] Care managementDue to the incurable and degenerative nature of the disease care-management of Alzheimer's is essential. The role of the main caregiver is often taken by the spouse or a close relative.[23] Caregivers may themselves suffer from stress, over-work, depression, and from being physically assailed.[24] Alzheimer's in societyFamous people who have, or have died of Alzheimer's disease, are the US president Ronald Reagan, the UK Prime minister Harold Wilson, the writers Terry Pratchett and Iris Murdoch, and the film stars Rita Hayworth and Charlton Heston. History Auguste D, first recorded patient with the newly recognised form of dementia. Alzheimer’s disease is named after Dr. Alois Alzheimer, the German physician who first described it. In 1901, Alzheimer observed a 51-year-old patient at the Frankfurt asylum named Auguste Deter. Her symptoms included memory loss, language problems, and unpredictable behavior. In 1906, she died and Dr. Alzheimer noticed unusual pathology in her brain tissue; he found many abnormal clumps (now called amyloid plaques) and tangled bundles of fibers (now called neurofibrillary, or tau, tangles). Prior to the early 20th century, Alzheimer's was undescribed in world medical literature. Other dementias and brain and behavioral disorders, however, were well documented by then. References

| ||||||||||||

Text in this section is transcluded from the respective Citizendium entries and may change when these are edited.

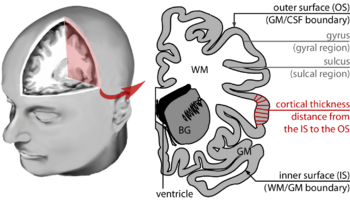

Brain morphometry is a subfield of both morphometry and the brain sciences, concerned with the measurement of brain structures and changes thereof during development, aging, learning, disease and evolution. Since autopsy-like dissection is generally impossible on living brains, brain morphometry starts with noninvasive neuroimaging data, typically obtained from magnetic resonance imaging (or MRI for short). These data are born digital, which allows researchers to analyze the brain images further by using advanced mathematical and statistical methods such as shape quantification or multivariate analysis. This allows researchers to quantify anatomical features of the brain in terms of shape, mass, volume (e.g. of the hippocampus, or of the primary versus secondary visual cortex), and to derive more specific information, such as the encephalization quotient, grey matter density and white matter connectivity, gyrification, cortical thickness, or the amount of cerebrospinal fluid. These variables can then be mapped within the brain volume or on the cortical surface, providing a convenient way to assess their pattern and extent over time, across individuals or even between different biological species. The field is rapidly evolving along with neuroimaging techniques — which deliver the underlying data — but also develops in part independently from them, as part of the emerging field of neuroinformatics, which is concerned with developing and adapting algorithms to analyze those data. (Read more...) |