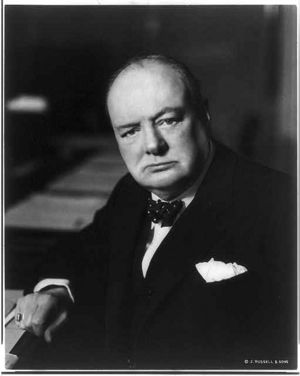

Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill (Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill) (30th November 1874 - 24th January 1965) was a leading world statesman of the twentieth century, best known as the Prime Minister who led Britain to victory over Nazi Germany in World War II. He was a longtime senior politician and orator, and gained renown (and a Nobel Prize in Literature) as a military historian. He was voted the greatest-ever Briton in the 2002 BBC poll, 100 Greatest Britons.[1]

Churchill was a younger son of the top aristocracy. Educated at Harrow and Sandhurst - and indeed largely self-educated, Churchill began as an officer in the British Army, gaining early fame for his war reporting from the Sudan and the Second Boer War. Entering politics in 1900 as a Conservative, he switched to the Liberal Party in 1906 and quickly became a party leader and senior office holder. During World War I Churchill was most prominent as civilian head of the Royal Navy (First Lord of the Admiralty), where he designed the failed attack on Turkey in the Gallipoli Campaign. He served in the important roles of Minister of Munitions, 1917-1918 and for War (1918-21). He was defeated for reelection in 1922 but returned in 1924 as a Conservative and became Chancellor of the Exchequer (1924-29). Out of power in the 1930s, he was a lone voice warning against Hitler and the Nazis, denouncing appeasement and calling for re-armament in preparation for war with Germany.

After the outbreak of the World War II Churchill returned to power as the First Lord of the Admiralty. Following the resignation of Neville Chamberlain in May 1940 Churchill became Prime Minister in a coalition government with Labour, Churchill was indefatigable in leading the British war effort against Germany; even at the darkest moments his speeches were an inspiration to the embattled British. He forged a close relationship with American President Franklin D. Roosevelt, starting in 1940. Together they proclaimed the "Atlantic Charter" in 1941. The U.S. became the "Arsenal of Democracy," sending munitions to Britain starting in 1940. Britain in turn sent munitions to Russia, as Churchill forged a treaty with Stalin. Europe was the centre of his attention, as the Australians complained about his neglect of their interests (and turned to the U.S. for protection). Recalling the horrible death tolls of 1914-1918, he was reluctant to invade France, proposing instead invasions of North Africa and Italy (which took place in 1942-43) and the Balkans (which did not happen). He strongly supported the strategic air campaign that bombed enemy cities, railyards and oil refineries. He worked very well with Dwight D. Eisenhower, the American general in overall command of the invasion of France that was launched successfully in June 1944. Despite complaints by senior generals and admirals that Churchill interfered too much in military matters, he was successful in balancing the economic, manpower, diplomatic, psychological and military dimensions of the war.

After losing the 1945 election Churchill became the Leader of the Opposition. In 1951 Churchill, despite the obvious frailties of his advanced age, again became Prime Minister before finally retiring in 1955. His six volume history of the war, written from his perspective, shaped the work of most subsequent historians. His state funeral saw one of the largest assemblies of statesmen in the world, as his reputation solidified as the great foe of the Nazis.

Early life

Churchill was the younger son of a the senior branch of the Spencer family, which added the surname Churchill to its own in the late eighteenth century. Churchill descended from the second member of the Churchill family to achieve public prominence, John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough. Winston's father, Lord Randolph Churchill, the third son of the 7th Duke of Marlborough was also a politician; Winston's mother, Lady Randolph Churchill (née Jennie Jerome), the daughter of American millionaire Leonard Jerome, was of colonial American stock of English ancestry. Churchill was born in Blenheim Palace in Woodstock, Oxfordshire. He had one brother, John Strange Spencer-Churchill.

Churchill had an independent and rebellious nature and generally did poorly in school, for which he was punished. He entered Harrow School in 1888. Soon he had joined the Harrow Rifle Corps.[2] Churchill earned high marks in English and history; he was also the school's fencing champion. He was rarely visited by his mother (then known as Lady Randolph), whom he loved very dearly, and wrote letters begging her to either come to the school or to allow him to come home.

Although Churchill had a distant relationship with his father, he followed his career closely. Churchill's lonely childhood haunted him throughout his life.

The Army

Sandhurst

After Churchill left Harrow in 1893, he attended the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. He graduated twentieth out of a class of 130 in December of 1894 and was immediately commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the 4th Queen's Own Hussars.

India

When Churchill finished training he asked to be posted to an area of action and was transferred to Bombay, India, in early October 1896. He was one of the best polo players in his regiment and led his team to many prestigious tournament victories. About this time he read Winwood Reade's Martyrdom of Man, a classic of Victorian atheism, which completed his loss of faith in orthodox Christianity and left him with a sombre vision of a godless universe in which humanity was destined, nevertheless, to progress through the conflict between the more advanced and the more backward races. He passed for a time through an aggressively anti-religious phase, but this eventually gave way to a more tolerant belief in the workings of some kind of divine providence.

In 1897, while preparing for a leave in England, Churchill heard that three brigades of the British Army were going to fight against a Pathan tribe; he asked his superior officer to join the fight. His account of the battle was one of his first published stories, for which he received £5 per column from the Daily Telegraph.

Later in 1897, young Churchill went to Bangalore, where he fought under the command of General Jeffery, who was the commander of the second brigade.

Cuba, India (again) and South Africa

In 1895 Churchill travelled to Cuba to observe the Spanish fight the Cuban guerrillas; he had obtained a commission to write about the conflict from the Daily Graphic. To Churchill's delight, he came under fire for the first time on his twenty-first birthday. He went to India to help quell the Pathan revolt on the North West Frontier. He had to ask his mother to pull some strings with some of her influential ex-lovers, including the Prince of Wales, to get permission to cover the battles

In late 1899 Churchill went to South Africa as a war correspondent to cover the Second Boer War in 1899. Caught in an ambush Churchill himself, however, was captured and held in a POW camp in Pretoria. Churchill escaped from his prison camp and travelled almost 300 miles (480 km) to Portuguese Lourenço Marques. His escape made him a minor national hero; instead of returning home, he rejoined General Redvers Buller's army on its march to relieve Ladysmith and take Pretoria. This time, although continuing as a war correspondent, Churchill gained a commission in the South African Light Horse Regiment. He was one of the first British troops into Ladysmith and Pretoria. In 1900, he published two books on the Boer war, London to Ladysmith via Pretoria and Ian Hamilton's March, which were published in May and October respectively.

Sudan and the Battle of Omdurman

While in India, Churchill used his family connections to get himself assigned to the army being put together and commanded by Lord Kitchener, who was assigned the reconquest of the Sudan. While in the Sudan, Churchill participated in what has been described as the last meaningful British cavalry charge at the Battle of Omdurman. He also served as a war correspondent for the Morning Post. By October 1898, he had returned to Britain and begun work on the two-volume The River War, published the following year.

Early years in Parliament

Churchill decided that the military did not suit him, so he entered upon a political career. Describing himself as a "Tory democrat," he stood as a Conservative candidate in Oldham in a by-election. He failed to be elected, coming in third (Oldham was at that time a two-seat borough). After a short time he was eligible to stand again. This time, in the 1900 general election, also called "the Khaki election]]," he was elected; but rather than attending the opening of Parliament, he embarked on a speaking tour throughout Britain and the United States, in the process raising ten thousand pounds for himself. (Members of Parliament were unpaid in those days and Churchill was not rich by the standards of other MPs at that time.)

In Parliament, Churchill became associated with a group of Tory dissidents led by Lord Hugh Cecil called the Hughligans, a play of words on "hooligans". During his first parliamentary session, Churchill provoked controversy by opposing what he viewed as the government's extravagant military expenditure. By 1903, he was drawing away from Lord Hugh's views. He also opposed the Liberal Unionist leader Joseph Chamberlain, whose party was in coalition with the Conservatives. In 1904, Churchill's dissatisfaction with the Conservatives had grown so strong that, he "crossed the floor" to sit as a member of the Liberal Party. As a Liberal, he continued to campaign for free trade. He won the seat of Manchester North West (carefully selected for him by the party- his electoral expenses were paid for by his uncle Lord Tweedmouth a senior Liberal in the 1906 general election. As a Liberal, Churchill played an instrumental role in passing social welfare legislation.

Ministerial office

Growing prominence

When the Liberals took office, with Henry Campbell-Bannerman as Prime Minister, in December 1905, Churchill became Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies, serving under Victor Bruce, 9th Earl of Elgin, Churchill dealt with the adoption of constitutions for the defeated Boer republics of the Transvaal and Orange River Colony and with the issue of 'Chinese slavery' in South African mines. He also became a prominent spokesman on free trade.

Churchill became the most prominent member of the Government outside the Cabinet, and when Campbell-Bannerman was succeeded by Herbert Henry Asquith in 1908, Churchill was promoted to the Cabinet as President of the Board of Trade. Under the law at the time, a newly appointed Cabinet Minister was obliged to seek re-election at a by-election. Churchill lost his Manchester seat to the Conservative but was soon elected in another by-election at Dundee constituency. As President of the Board of Trade, he pursued radical social reforms known as the Liberal reforms, enacted in conjunction with David Lloyd George, the new Chancellor of the Exchequer. Most notable amongst these was the People's Budget that led to the downfall of the House of Lords as well as the opposition of Navy building by then First Lord of the Admiralty, Reginald McKenna.

In 1910, Churchill was promoted to Home Secretary, where he was to prove somewhat controversial. A famous photograph from the time shows the impetuous Churchill at the scene of the January 1911 Sidney Street Siege, peering around a corner to view a gun battle between cornered anarchists and Scots Guards. His role attracted much criticism. The building under siege caught fire and Churchill supported the decision to deny the fire brigade access, forcing the criminals to choose surrender or death. Arthur Balfour asked, "He [Churchill] and a photographer were both risking valuable lives. I understand what the photographer was doing but what was the Right Honourable gentleman doing?"

1910 also saw Churchill preventing the army being used to deal with a dispute at the Cambrian Colliery mine in Tonypandy. Initially, Churchill blocked the use of troops fearing a repeat of the 1887 'bloody Sunday' in Trafalgar Square. Nevertheless, troops were deployed to protect the mines and to avoid riots when thirteen strikers were tried for minor offences, an action that broke the tradition of not involving the military in civil affairs and led to lingering dislike for Churchill in Wales.

First Lord of the Admiralty

In 1911, Churchill became First Lord of the Admiralty, a post he held into World War I. He gave impetus to reform efforts, including development of naval aviation, tanks, and the switch in fuel from coal to oil.

He promoted the development of tanks, hoping they would break through trenches, barbed wire and machine gun fire.

In 1915, Churchill was the chief promoter of the Gallipoli strategy, which failed miserably. He took much of the blame for the fiasco, and when Prime Minister Asquith formed an all-party coalition government, the Conservatives demanded Churchill's demotion as the price for entry. For several months Churchill served as "Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster", before resigning from the government. He rejoined the army, though remaining an MP, and served for several months on the Western Front commanding the 6th Battalion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers.

Return to power

In December 1916, Asquith resigned as Prime Minister and was replaced by David Lloyd George. The time was thought not yet right to risk the Conservatives' wrath by bringing Churchill back into government. However, in July 1917, Churchill was appointed Minister of Munitions, and in January 1919, Secretary of State for War and Secretary of State for Air. He was the main architect of the Ten Year Rule, but the major preoccupation of his tenure in the War Office was the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War. Churchill was a staunch advocate of foreign intervention, declaring that Bolshevism must be "strangled in its cradle".[3] He secured, from a divided and loosely organised Cabinet, intensification and prolongation of the British involvement beyond the wishes of any major group in Parliament or the nation — and in the face of the bitter hostility of Labour. In 1920, after the last British forces had been withdrawn, Churchill was instrumental in having arms sent to the Poles when they invaded Ukraine.

He became Secretary of State for the Colonies in 1921 and was a signatory of the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, which established the Irish Free State. Churchill always disliked Éamon de Valera, the Sinn Féin leader. Churchill, to protect British maritime interests engineered the Irish Free State agreementTemplate:Fact to include three Treaty Ports — Queenstown (Cobh), Berehaven and Lough Swilly — which could be used as Atlantic bases by the Royal Navy. Under cuts instituted by Churchill as Chancellor of the Exchequer and others, the bases were neglected. Under the terms of the Anglo-Irish Trade Agreement the bases were returned to the newly constituted Éire in 1938.

As Colonial Secretary he advocated the use of poison gas against tribesmen revolting in what was soon to become Iraq. He did however set up a Middle East Department of the Colonial Office and under the instigation of T E Lawrence (who had earlier been dispatched to the Middle East by Lord Curzon ) he supported the claims of Feisal and Abdullah as Kings of Iraq and Jordan respectively (James op cit 172)

Career between the wars

Second crossing of the floor

In 1920, as Secretary for War and Air, Churchill had responsibility for using air power to quell the rebellion of Kurds and Arabs in British-occupied Iraq.

With the 1922 election looming, Churchill's Liberal Party was internally split. He lost badly, and lost again (as a Liberal) in 1923 and as an independent in a by-election. Running in 1924 as a "Constitutionalist" with Conservative backing, he was elected to represent Epping. In 1925, he formally rejoined the Conservative Party, commenting wryly that "Anyone can rat [change parties], but it takes a certain ingenuity to re-rat."

Chancellor of the Exchequer

He was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1924 under Stanley Baldwin and oversaw Britain's disastrous return to the Gold Standard, which resulted in deflation, unemployment, and the miners' strike that led to the General Strike of 1926. This decision prompted the economist John Maynard Keynes to write The Economic Consequences of Mr. Churchill, arguing that the return to the gold standard at the pre-war parity in 1925 (£1=$4.86) would lead to a world depression. Interestingly, the pamphlet did not criticise the decision to return to the gold standard per se. Churchill later regarded this as the greatest mistake of his life; he stated he was not an economist and that he acted on the advice of the Governor of the Bank of England, Montagu Norman. However in discussions at the time with McKenna, himself a former Chancellor Churchill acknowledged that the return to the gold standard and the resulting 'dear money' policy was economically bad. In those discussions he maintained the policy as fundamentally political - a return to the pre war conditions in which he believed (James op cit 206)

During the General Strike of 1926, Churchill was reported to have suggested that machine guns be used on the striking miners. Churchill edited the Government's newspaper, the British Gazette, and, during the dispute, he argued that "either the country will break the General Strike, or the General Strike will break the country." Furthermore, he controversially claimed that the Fascism of Benito Mussolini had "rendered a service to the whole world," showing, as it had, "a way to combat subversive forces" — that is, he considered the regime to be a bulwark against the perceived threat of Communist revolution. At one point, Churchill went as far as to call Mussolini the "Roman genius… the greatest lawgiver among men."[4]

Political isolation

The Conservative government was defeated in the 1929 General Election. In the next two years, Churchill became estranged from the Conservative leadership over the issues of protective tariffs and Indian Home Rule, which he bitterly opposed. When Ramsay MacDonald formed the National Government in 1931, Churchill was not invited to join the Cabinet. He was now at the low point in his career, in a period known as "the wilderness years".

He spent much of the next few years concentrating on his writing, including Marlborough: His Life and Times — a biography of his ancestor John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough — and A History of the English Speaking Peoples (which was not published until well after World War II). When struck by a taxi he wrote an article about the experience. He supported himself largely by his writing and was one of the best paid writers of his time. HE spent so much time in writing that he rarely attended Parliament unless he intended making a speech. He continued writing A History of the English Speaking Peoples while First Lord of the Admiralty at the height of the Norwegian campaign (Cannadine op cit p 46)

He became most notable for his outspoken opposition towards the granting of independence to India (see Simon Commission and Government of India Act 1935).He denigrated the father of the Indian independence movement, Mahatma Gandhi, as "a half-naked fakir" who "ought to be laid, bound hand and foot, at the gates of Delhi and then trampled on by an enormous elephant with the new viceroy seated on its back." His views on India were set by his experience as a junior cavalry officer stationed in India in the 1890s and are shown in his book My Early Life which was published in 1930 (See James op cit 257f). He helped found the India Defence League a group dedicated to the preservation of British power in India. In speeches and press articles in this period he forecast widespread British unemployment and civil strife in India should independence be granted to India. (James op cit 260). He opposed the official government policy both in and out of parliament. On the eve of the St George by election in which an independent supported by Lord Rothermere and Lord Beaverbrook and their respective newspapers stood against Duff Cooper the official conservative candidate he spoke at a rally in which he attacked Baldwin's policy.

Soon, though, his attention was drawn to the rise of Adolf Hitler and the dangers of Germany's rearmament. For a time, he was a lone voice calling on Britain to strengthen itself to counter the belligerence of Germany.[5] Churchill was a fierce critic of Neville Chamberlain's appeasement of Hitler, leading the wing of the Conservative Party that opposed the Munich Agreement which Chamberlain famously declared to mean "peace in our time".[6] He was also an outspoken supporter of King Edward VIII during the Abdication Crisis, leading to some speculation that he might be appointed Prime Minister if the King refused to take Baldwin's advice and consequently the government resigned. However, this did not happen, and Churchill found himself politically isolated and bruised for some time after this.

Role as wartime Prime Minister

"Winston is back"

After the outbreak of the Second World War Churchill was appointed First Lord of the Admiralty and a member of the War Cabinet, just as he was in the first part of the First World War. The Navy sent out the signal: "Winston is back."[7]

In this job, he proved to be one of the highest-profile ministers during the so-called "Phony War", when the only noticeable action was at sea. Churchill advocated the pre-emptive occupation of the neutral Norwegian iron-ore port of Narvik and the iron mines in Kiruna, Sweden, early in the War. However, Chamberlain and the rest of the War Cabinet disagreed, and the operation was delayed until the German invasion of Norway, which was successful despite British efforts.

Bitter beginnings of the war

On 10 May 1940, hours before the German invasion of France by a lightning advance through the Low Countries, it became clear that, following failure in Norway, the country had no confidence in Chamberlain's prosecution of the war and so Chamberlain resigned. The commonly accepted version of events states that Lord Halifax turned down the post of Prime Minister because he believed he could not govern effectively as a member of the House of Lords instead of the House of Commons. Although traditionally, the Prime Minister does not advise the King on the former's successor, Chamberlain wanted someone who would command the support of all three major parties in the House of Commons. A meeting between Chamberlain, Halifax, Churchill and David Margesson, the government Chief Whip, led to the recommendation of Churchill, and, as a constitutional monarch, George VI asked Churchill to be Prime Minister and to form an all-party government. Churchill's first act was to write to Chamberlain to thank him for his support.[8]

Churchill's greatest achievement was that he refused to capitulate when defeat by Germany was a strong possibility and all seemed hopeless, and he remained a strong opponent of any negotiations with Germany. Few others in the Cabinet had this degree of resolve. By adopting a policy of no surrender, Churchill kept democracy alive in the UK and created the basis for the later Allied counter-attacks of 1942-45, with Britain serving as a platform for the supply of Soviet Russia and the liberation of Western Europe.

Among the many consequences of this stand was that Britain was maintained as a base from which the Allies could attack Germany, thereby ensuring that the Soviet sphere of influence did not extend over Western Europe at the end of the war.

In response to previous criticisms that there had been no clear single minister in charge of the prosecution of the war, Churchill created and took the additional position of Minister of Defence. He immediately put his friend and confidant, the industrialist and newspaper baron Lord Beaverbrook, in charge of aircraft production. It was Beaverbrook's business acumen that allowed Britain to quickly gear up aircraft production and engineering that eventually made the difference in the war.

Churchill's speeches were a great inspiration to the embattled British. His first speech as Prime Minister was the famous "I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears, and sweat" speech. He followed that closely with two other equally famous ones, given just before the Battle of Britain. One included the immortal line, "We shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender." The other included the equally famous "Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves that, if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, 'This was their finest hour.' "

At the height of the Battle of Britain, his bracing survey of the situation included the memorable line "Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few", which engendered the enduring nickname "The Few" for the Allied fighter pilots who won it. One of his most memorable war speeches came on 10 November 1942 at the Lord Mayor's Luncheon at Mansion House in London, in response to the Allied victory at the Second Battle of El Alamein. Churchill famously said:

"This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning."

Without having much in the way of sustenance or good news to offer the British people, he took a political risk in deliberately choosing to emphasize the dangers instead.

"Rhetorical power," wrote Churchill, "is neither wholly bestowed, nor wholly acquired, but cultivated."

Relations with the United States

His good relationship with Franklin D. Roosevelt secured vital food, oil and munitions via the North Atlantic shipping routes. It was for this reason that Churchill was relieved when Roosevelt was re-elected in 1940. Upon re-election, Roosevelt immediately set about implementing a new method of providing military hardware and shipping to Britain without the need for monetary payment. Put simply, Roosevelt persuaded Congress that repayment for this immensely costly service would take the form of defending the USA; and so Lend-lease was born. Churchill had 12 strategic conferences with Roosevelt which covered the Atlantic Charter, Europe first strategy, the Declaration by the United Nations and other war policies. On 26 December 1941 Churchill addressed a joint session of the U.S. Congress, asking of Germany and Japan, "What kind of people do they think we are?".[9] Churchill initiated the Special Operations Executive (SOE) under Hugh Dalton's Ministry of Economic Warfare, which established, conducted and fostered covert, subversive and partisan operations in occupied territories with notable success; and also the Commandos which established the pattern for most of the world's current Special Forces. The Russians referred to him as the "British Bulldog".

Churchill's health suffered, as shown by a mild heart attack he suffered in December 1941 at the White House and also in December 1943 when he contracted pneumonia. Despite this, he travelled over 100,000 miles throughout the war to meet other national leaders. For security, he usually travelled using the alias Colonel Warden.[10]

Churchill was party to treaties that would redraw post-World War II European and Asian boundaries. These were discussed as early as 1943. Proposals for European boundaries and settlements were officially agreed to by Harry S. Truman, Churchill, and Stalin at Potsdam. At the second Quebec Conference in 1944 he drafted and together with U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed a toned down version of the original Morgenthau Plan, where they pledged to convert Germany after its unconditional surrender "into a country primarily agricultural and pastoral in its character."[11]

Relations with the Soviet Union

The settlement concerning the borders of Poland, that is, the boundary between Poland and the Soviet Union and between Germany and Poland, was viewed as a betrayal in Poland during the post-war years, as it was established against the views of the Polish government in exile. Churchill was convinced that the only way to alleviate tensions between the two populations was the transfer of people, to match the national borders. As he expounded in the House of Commons in 1944, "Expulsion is the method which, insofar as we have been able to see, will be the most satisfactory and lasting. There will be no mixture of populations to cause endless trouble... A clean sweep will be made. I am not alarmed by these transferences, which are more possible in modern conditions." However the resulting expulsions of Germans was carried out by the Soviet Union in a way which resulted in much hardship and, according to a 1966 report by the West German Ministry of Refugees and Displaced Persons, the death of over 2,100,000. Churchill opposed the effective annexation of Poland by the Soviet Union and wrote bitterly about it in his books, but he was unable to prevent it at the conferences.

On 9 October 1944, he and Eden were in Moscow, and that night they met Joseph Stalin in the Kremlin, without the Americans. Bargaining went on throughout the night. Churchill wrote on a piece of paper that Stalin had a 90 percent "interest" in Romania, Britain a 90 percent "interest" in Greece and a 100 percent "interest" in Italy, both Russia and Britain a 50 percent "interest" in Yugoslavia. The crucial questions arose when the Ministers of Foreign Affairs discussed "percentages" in Eastern Europe. Molotov's proposals were that Russia should have a 75 percent interest in Hungary, 75 percent in Bulgaria, and 60 percent in Yugoslavia. This was Stalin's price for ceding Italy and Greece. Eden tried to haggle: Hungary 75/25, Bulgaria 80/20, but Yugoslavia 50/50. After lengthy bargaining they settled on an 80/20 division of interest between Russia and Britain in Bulgaria and Hungary, and a 50/50 division in Yugoslavia. U.S. Ambassador Averell Harriman was informed only after the bargain was struck. This gentleman's agreement was sealed with a handshake.[12]

After World War II

Although the importance of Churchill's role in World War II was undeniable, he had many enemies in his own country. He expressed contempt for a number of popular ideas, in particular public health care and better education for the majority of the population, and produced much dissatisfaction amongst the population, particularly those who had fought in the war.Template:Fact Immediately following the close of the war in Europe, Churchill was heavily defeated in the 1945 election by Clement Attlee and the Labour Party.[13] Some historians think that many British voters believed that the man who had led the nation so well in war was not the best man to lead it in peace. Others see the election result as a reaction not against Churchill personally, but against the Conservative Party's record in the 1930s under Baldwin and Chamberlain. During the opening broadcast of the election campaign Churchill astonished many of his admirers by warning that a Labour government would introduce into Britain "some form of Gestapo, no doubt humanely administered in the first instance". Churchill had been genuinely worried during the war by the inroads of state bureaucracy into civil liberty, and was clearly influenced by Friedrich Hayek's anti-totalitarian tract, The Road to Serfdom (1944).

Winston Churchill was an early supporter of the pan-Europeanism that eventually led to the formation of the European Common Market and later the European Union (for which one of the three main buildings of the European Parliament is named in his honour). However, this is often seen as his supporting Britain's membership in that pan-Europeanism, which is far from the truth. Rather, he saw Pan Europeanism as a Franco-German project which would foster cooperation amongst European countries and the rest of the world and prevent war on the European continent.This can be seen in Churchill’s landmark refusal to join the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 1951 as well as his often quoted speech in which he said of Britain's role with Europe:

We have our own dream and our own task. We are with Europe, but not of it. We are linked but not combined.We are interested and associated but not absorbed.[14]

This stance has, arguably, shaped Britain's feelings toward European integration and its subsequent general ambivalence towards all things Europe. He much more saw Britain's place as separate from the continent, much more in-line with the countries of the Commonwealth and the Empire and with the United States, the so-called Anglosphere.As evidenced in his speech at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, given on 5 March 1946 where as a guest of Harry S. Truman, he declared:

The sure prevention of war, nor the continuous rise of world organisation will be gained without what I have called the fraternal association of the English-speaking peoples. This means a special relationship between the British Commonwealth and Empire and the United States.[15]

It was also during this speech that he famously popularised the term "The Iron Curtain":

From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an Iron Curtain has descended across the continent. Behind that line lie all the capitals of the ancient states of Central and Eastern Europe. Warsaw, Berlin, Prague, Vienna, Budapest, Belgrade, Bucharest and Sofia, all these famous cities and the populations around them lie in what I must call the Soviet sphere.[15]

Churchill was instrumental in giving France a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council (which provided another European power to counterbalance the Soviet Union's permanent seat).

Second term

Churchill was restless and bored as leader of the Conservative opposition in the immediate post-war years. After Labour's defeat in the General Election of 1951, Churchill again became Prime Minister. His third government — after the wartime national government and the brief caretaker government of 1945 — would last until his resignation in 1955. During this period, he renewed what he called the "special relationship" between Britain and the United States, and engaged himself in the formation of the post-war order. On racial questions, Churchill was still a late Victorian. He tried in vain to manoeuvre the cabinet into restricting West Indian immigration. "Keep England White" was a good slogan, he told the cabinet in January 1955.[16]

His domestic priorities were, however, overshadowed by a series of foreign policy crises, which were partly the result of the continued decline of British military and imperial prestige and power. Being a strong proponent of Britain as an international power, Churchill would often meet such moments with direct action. Trying to retain what he could of the Empire, he once stated that, "I will not preside over a dismemberment."

The Mau Mau Rebellion

In 1951, grievances against the colonial distribution of land came to a head with the Kenya Africa Union demanding greater representation and land reform. When these demands were rejected, more radical elements came forward, launching the Mau Mau rebellion in 1952. On 17 August 1952, a state of emergency was declared, and British troops were flown to Kenya to deal with the rebellion. As both sides increased the ferocity of their attacks, the country moved to full-scale civil war.

In 1953, the Lari massacre, perpetrated by Mau-Mau insurgents against Kikuyu loyal to the British, changed the political complexion of the rebellion and gave the public-relations advantage to the British. Churchill's strategy was to use a military stick combined with implementing many of the concessions that Attlee's government had blocked in 1951. He ordered an increased military presence and appointed General Sir George Erskine, who would implement Operation Anvil in 1954 that broke the back of the rebellion in the city of Nairobi. Operation Hammer, in turn, was designed to root out rebels in the countryside. Churchill ordered peace talks opened, but these collapsed shortly after his leaving office.

Malayan Emergency

In Malaya, a rebellion against British rule had been in progress since 1948. Once again, Churchill's government inherited a crisis, and once again Churchill chose to use direct military action against those in rebellion while attempting to build an alliance with those who were not. He stepped up the implementation of a "hearts and minds" campaign and approved the creation of fortified villages, a tactic that would become a recurring part of Western military strategy in South-east Asia. (See Vietnam War).

The Malayan Emergency was a more direct case of a guerrilla movement, centred in an ethnic group, but backed by the Soviet Union. As such, Britain's policy of direct confrontation and military victory had a great deal more support than in Iran or in Kenya. At the highpoint of the conflict, over 35,500 British troops were stationed in Malaya. As the rebellion lost ground, it began to lose favour with the local population.

While the rebellion was slowly being defeated, it was equally clear that colonial rule from Britain was no longer plausible. In 1953, plans were drawn up for independence for Singapore and the other crown colonies in the region. The first elections were held in 1955, just days before Churchill's own resignation.

Stroke

In June 1953, when he was 78, Churchill suffered a stroke after a meeting with the Italian Prime Minister at No. 10 Downing Street. News of this was kept from the public and from Parliament, who were told that Churchill was suffering from exhaustion. He went to his country home, Chartwell, to recuperate from the effects of the stroke which had affected his speech and ability to walk. He returned to public life in October to make a speech at a Conservative Party conference at Margate, having decided that if he couldn't make the speech, he would retire as Prime Minister — but he was able to deliver it without problems.

Family and personal life

On 12 September, 1908, Churchill married Clementine Hozier, granddaughter of the 7th Earl of Airlie. They had five children: Diana; Randolph; Sarah; Marigold]] (1918–21); and Mary. Churchill's son Randolph and his grandsons Parliament. The daughters tended to marry politicians and support their careers. When not in London, Churchill usually lived at his beloved Chartwell House in Kent, two miles south of Westerham. He and his wife bought the house in 1922 and lived there until his death in 1965. During his Chartwell stays, he enjoyed writing as well as painting, bricklaying, and admiring the estate's famous black swans.

As a painter he was prolific, with over 570 paintings and two sculptures; he received a Diploma from the Royal Academy of London. Like many politicians of his age, Churchill was also a member of several English gentlemen's clubs; he spent relatively little time in each of these, and preferred to conduct any lunchtime or dinner meetings at the Savoy Grill or the Ritz hotel, or else in the Members' Dining Room of the House of Commons when meeting other MPs.

Churchill's fondness for alcoholic beverages was well-documented. He consumed alcoholic drinks on a near-daily basis for long periods in his life, and frequently imbibed before, after, and during mealtimes. He is not generally considered by historians to have been an alcoholic.

- For much of his life, Churchill battled with depression (or perhaps a sub-type of manic-depression), which he called his black dog.[17]

- Churchill was recognised for his trademark cigar, suit with bow tie and his red hair, (which became sandy as he grew older).

Last days

Aware that he was slowing down both physically and mentally, Churchill retired as Prime Minister in 1955 and was succeeded by Anthony Eden, who had long been his ambitious protégé (three years earlier, Eden had married Churchill's niece). He declined a dukedom to stay in the House, sometimes voting in parliamentary divisions, but never again speaking there. In 1959, he became Father of the House, the MP with the longest continuous service. Churchill spent most of his retirement at Chartwell House in Kent, two miles south of Westerham.

As Churchill's mental and physical faculties decayed, he began to lose the battle he had fought for so long against the ["black dog"] of depression. He found some solace in the sunshine and colours of the Mediterranean. In 1963, U.S. President John F. Kennedy proclaimed Churchill the first "Honorary Citizen of the United States."

Churchill's final years were melancholy. He never resolved the love–hate relationship between himself and his son. Sarah was descending into alcoholism and Diana committed suicide in the autumn of 1964. Churchill himself suffered a number of minor strokes. It was a figure ravaged by age and sorrow who appeared at the window of his London home, 28 Hyde Park Gate, to greet the photographers on his ninetieth birthday in November 1964.

On 15 January, 1965, Churchill suffered another stroke — a severe cerebral thrombosis — that left him gravely ill. He died at his home nine days later, at age 90.

Funeral

By decree of the Queen, his body lay in state for three days and a state funeral service was held at St Paul's Cathedral.[18] This was the first state funeral for a non-royal family member since 1914, and no other of its kind has been held since.

At Churchill's request, he was buried in the family plot at St Martin's Church, Bladon, near Woodstock, not far from his birthplace at Blenheim. Churchill's estate was probated at £304,044.

Churchill as historian

From 1903 until 1905, Churchill wrote Lord Randolph Churchill, a two-volume biography of his father which was published in 1906 and received much critical acclaim. However, filial devotion caused him to soften some of his father's less attractive aspects. Some historians suggest Churchill used the book in part to vindicate his own career and in particular to justify crossing the floor.[19]

Bibliography

Biographies

- Addison, Paul. Churchill: The Unexpected Hero. Oxford U. Press, 2005. 208 pp.

- Best, Geoffrey. Churchill: A Study in Greatness (2003)

- Blake, Robert. Winston Churchill. Pocket Biographies (1997), 110 pages

- Browne, A. Montague Long sunset 1995

- Charmley, John. Churchill, The End of Glory: A Political Biography (1993). revisionist; favors Chamberlain; says Churchill weakened Britain

- Gilbert, Martin. Churchill: A Life (1992) ; one volume version of 8-volume life (8900 pp); amazing detail but as Rasor complains, "no background, no context, no comment, no analysis, no judgments, no evaluation, and no insights."

- Heywood, Samantha. Churchill (2003) 162pp, online edition

- James, Robert Rhodes. Churchill: A Study in Failure, 1900-1939 (1970), 400 pp.

- Jenkins, Roy. Churchill: A Biography (2001)

- Krockow, Christian. Churchill: Man of the Century 2000

- Lukacs, John. Churchill: Visionary, Statesman, Historian Yale University Press, 2002.

- Manchester, William. The Last Lion: Winston Spencer Churchill, Visions of Glory 1874-1932, 1983; vol 2 is The Last Lion: Winston Spencer Churchill, Alone 1932-1940, 1988, ; no more published

- Pelling, Henry. Winston Churchill (1974), 736pp; comprehensive biography

- Wrigley, Chris. Winston Churchill: A Biographical Companion. ABC-CLIO, 2002. 367 pp.

Specialized studies

- Beschloss, Michael R. The Conquerors: Roosevelt, Truman and the Destruction of Hitler's Germany, 1941-1945 (2002)

- Best, Geoffrey. Churchill and War. 2005. 353 pp.

- Blake, Robert and Louis William Roger, eds. Churchill: A Major New Reassessment of His Life in Peace and War Oxford UP, 1992, 581 pp; 29 essays by scholars on specialized topicsonline edition

- Callahan, Raymond. Churchill and His Generals, (2007) 310pp

- Charmley, John. Churchill's Grand Alliance: The Anglo-American Special Relationship 1940-57 (1996)

- Delaney, Douglas E. "Churchill and the Mediterranean Strategy: December 1941 to January 1943." Defence Studies 2002 2(3): 1-26. Issn: 1470-2436 Fulltext: in Ebsco

- Kersaudy, François. Churchill and De Gaulle 1981

- Larres, Klaus. Churchill's Cold War: The Politics of Personal Diplomacy. Yale U. Press, 2002. 569 pp.

- Massie, Robert Dreadnought: Britain, Germany and the Coming of the Great War; ch 40-41 on Churchill at Admiralty

Historiography

- Ramsden, John. Man of the Century: Winston Churchill and His Legend since 1945. Columbia U. Press, 2003. 672 pp.

- Rasor, Eugene L. Winston S. Churchill, 1874-1965: A Comprehensive Historiography and Annotated Bibliography. Greenwood Press. 2000. 710 pp. describes several thousand books and scholarly articles. online edition

- Reynolds, David. In Command of History: Churchill Fighting and Writing the Second World War. 2005. 631 pp.

- Stansky, Peter, ed. Churchill: A Profile 1973, 270 pp. essays for and against Churchill by leading scholars

Primary sources

- Churchill, Winston. The World Crisis (six volumes, 1923–31), 1-vol edition (2005); on World War I

- Churchill, Winston. The Second World War (six volumes, 1948–53)

- Gilbert, Martin, ed. Winston S. Churchill: Companion 15 vol (14,000 pages) of Churchill and other official and unofficial documents. Part 1: I. Youth, 1874-1900, 1966, 654 pp. (2 vol); II. Young Statesman, 1901-1914, 1967, 796 pp. (3 vol); III. The Challenge of War, 1914-1916, 1971, 1024 pp. (3 vol); IV. The Stricken World, 1916-1922, 1975, 984 pp. (2 vol); Part 2: The Prophet of Truth, 1923-1939, 1977, 1195 pp. (3 vol); II. Finest Hour, 1939-1941, 1983, 1328 pp. (2 vol entitled The Churchill War Papers); III. Road to Victory, 1941-1945, 1986, 1437 pp. (not published, 4 volumes are anticipated); IV. Never Despair, 1945-1965, 1988, 1438 pp. (not published, 3 volumes anticipated, See the editor's memoir, Martin Gilbert, In Search of Churchill: A Historian's Journey, (1994).

- James, Robert Rhodes, ed. Winston S. Churchill: His Complete Speeches, 1897-1963. 8 vols. London: Chelsea, 1974, 8917 pp.

- Sir Winston Churchill, His life through his paintings, David Coombs, Pegasus, 2003

- Winston Churchill and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Roosevelt and Churchill: Their Secret Wartime Correspondence ed by

Francis L. Loewenheim, Harold D. Langley and Manfred Jonas (1975) 807 pgs online edition

External links

- Works by Winston Churchill at Project Gutenberg

- Churchill College Biography of Winston Churchill

- Havengore carried Sir Winston Churchill along the Thames during his State Funeral

- Sir Winston Churchill Quotes

- Books written by Churchill

- Imperial War Museum: Churchill Museum and Cabinet War Rooms. Comprising the original underground War Rooms perfectly preserved since 1945, from which Churchill ran the War, including the Cabinet Room, the Map Room and Churchill's bedroom, and the new Museum dedicated to Churchill's life.

- Winston Churchill Chronology World History Database

- The Churchill Centre website

- Churchill Video Speech, We Stood Alone

- Rethinking Churchill, Parts 1 to 5

- Winston Churchill in Cuba

- Opinion piece on Churchill's significance in history.

- Another bio of him including extended quotations from his speeches

- Churchill and the Great Republic. Exhibition explores Churchill's lifelong relationship with the United States.

- Winston Churchill and the Bombing of Dresden UK National Archives documents.

- Audio about the Winston Churchill Memorial and Library at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri from the Speaking of History podcast #17 - site also includes video slideshow of the museum

- War Cabinet Minutes (1942 - 42), (1942 - 43), (1945 - 46), (1946 - 46)

- MCE European NAvigator European Union History tool, contains a number of Churchill recordings etc.

- The Real Churchill (critical)

- Essay: Churchill and the Crucible of History

- More about Winston Churchill on the Downing Street website.

Speeches

- http://www.churchill-speeches.com/

- Audio of Churchill's "finest hour" speech

- Timeline of the Spencer-Churchill family

- Winston Churchill Audio Soundboard

References

- ↑ Poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.

- ↑ http://www.winstonchurchill.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=638

- ↑ Jeffrey Wallin with Juan Williams (2001-09-04). Cover Story: Churchill's Greatness.. Churchill Centre. Retrieved on 2007-02-26.

- ↑ Picknett, Lynn, Prince, Clive, Prior, Stephen & Brydon, Robert (2002). War of the Windsors: A Century of Unconstitutional Monarchy, p. 78. Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 1-84018-631-3.

- ↑ Picknett, et al., p. 75.

- ↑ Picknett, et al., pp. 149–50.

- ↑ Brendon, Piers. The Churchill Papers: Biographical History. Churchill Archives Centre, Churchill College, Cambridge. Retrieved on 2007-02-26.

- ↑ Self, Robert (2006). Neville Chamberlain: A Biography, p. 431. Ashgate. ISBN 9-780754-656159.

- ↑ http://www.ibiblio.org/pha/policy/1941/411226a.html

- ↑ Books About Winston Churchill. Chartwell Booksellers. Retrieved on 2007-02-26.

- ↑ Michael R. Beschloss, (2002) ‘’The Conquerors’’ : pg. 131

- ↑ Historical Papers: Documents from the British Archives

- ↑ Picknett, et al., p. 190.

- ↑ Remembrance Day 2003. Churchill Society London. Retrieved on 2007-04-25.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Churchill, Winston. Sinews of Peace (Iron Curtain). Churchill Centre. Retrieved on 2007-02-26.

- ↑ Hennessy, p. 205

- ↑ Black Dog, PBS.

- ↑ Picknett, et al., p. 252.

- ↑ Cannadine p 41, James, Churchill a study in failure p34-35