Evolution of appetite regulating systems: Difference between revisions

imported>Sophie A. Clarke No edit summary |

imported>Sophie A. Clarke No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{CZ:(U00984) Appetite and Obesity, University of Edinburgh 2010/EZnotice}} | {{CZ:(U00984) Appetite and Obesity, University of Edinburgh 2010/EZnotice}} | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

Recently, there has been extensive research into the neuroendocrine mechanisms controlling appetite. The [[pro-opiomelanocortin]] (POMC) gene has an important role in these mechanisms, particularly through production of [[alpha melanocyte stimulating hormone]] ( | Recently, there has been extensive research into the neuroendocrine mechanisms controlling appetite. The [[pro-opiomelanocortin]] (POMC) gene has an important role in these mechanisms, particularly through production of [[alpha melanocyte stimulating hormone]] (α-MSH). POMC and its end-products have not only been identified in humans, but also in many other vertebrates. This has led to further research into the origins of the POMC gene and the '''evolution of appetite regulating systems'''. | ||

This article details the structure and function of the POMC gene. It highlights variations between species, allowing a potential evolutionary route, originating at a common ancestral gene, to be mapped out. | This article details the structure and function of the POMC gene. It highlights variations between species, allowing a potential evolutionary route, originating at a common ancestral gene, to be mapped out. | ||

Revision as of 09:06, 14 November 2010

For the course duration, the article is closed to outside editing. Of course you can always leave comments on the discussion page. The anticipated date of course completion is 01 February 2011. One month after that date at the latest, this notice shall be removed. Besides, many other Citizendium articles welcome your collaboration! |

Recently, there has been extensive research into the neuroendocrine mechanisms controlling appetite. The pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) gene has an important role in these mechanisms, particularly through production of alpha melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH). POMC and its end-products have not only been identified in humans, but also in many other vertebrates. This has led to further research into the origins of the POMC gene and the evolution of appetite regulating systems. This article details the structure and function of the POMC gene. It highlights variations between species, allowing a potential evolutionary route, originating at a common ancestral gene, to be mapped out.

Human POMC

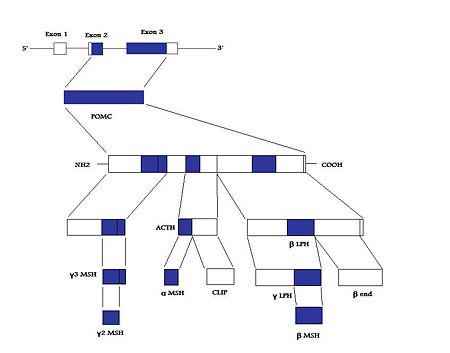

The human POMC gene encodes a hormone precursor protein, which is then cleaved by prohormone convertase enzymes into a number of different peptides. These include the melanocyte-stimulating hormones (alpha-, beta-, gamma- MSH), adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), the lipotropins, and beta-endorphin [1]. ACTH and the MSHs are referred to as the melanocortins, and all have the same core amino acid sequence, HFRW [2].

The human POMC gene is on chromosome 2p23[3], and has three exons and two “large” introns[4]. Only exons two and three are translated; exon two codes for the signal peptide and the initial N-terminal amino acids, while exon three codes for “most of the translated mRNA” [3].

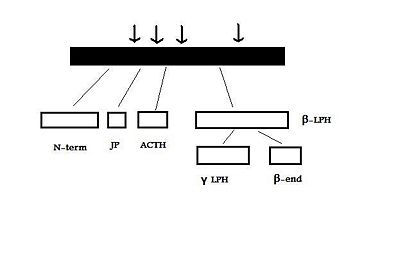

After excision of the introns to form a “parent” POMC, this molecule is then cleaved into its various peptides, as mentioned above, by PCs, specifically PC1 and PC2[4]. These enzymes act at cleavage sites consisting of paired basic residues, arginine and lysine, and end-products of their action depend on which sites are used. As PC1 and PC2 act on different sites, and their expression varies in different tissues, processing of POMC peptides is tissue-specific [3]. For example, the anterior pituitary corticotroph cells only express PC1, which results in the cleavage of POMC into the NH2-terminal peptide (N-term), joining peptide (JP), ACTH, β-LPH, and some γ-LPH and β-endorphin (β-end) - See "POMC cleavage by PC1" diagram. The latter two peptides are produced because the “last cleavage site is only partially used”[3]. However, in melanotroph cells, found in the intermediate lobe of the rodent pituitary, and the human hypothalamus, and placenta, both PC1 and PC2 are expressed. This means that all the cleavage sites are used and smaller peptides are produced [4]). N-term is therefore cleaved to the γ-MSHs, ACTH gives rise to α-MSH and CLIP (corticotropin-like intermediate lobe peptide) and γ-LPH to β-MSH[3].

The POMC gene is expressed in number of tissues in man and animals. These include the anterior, and intermediate (only in rodents) lobes of the pituitary gland. It is also present in the nucleus tractus solitarii of the caudal medulla, and the hypothalamus, specifically the arcuate nucleus[4]. Its expression has also been noted in the skin and the immune system[1],as well as other peripheral tissues.

The final products from the cleavage of POMC have a variety of functions. The melanocortins act on melanocortin receptors (MCRs) in different tissues. There are five types of MCR, and different melanocortin peptides bind to these with different affinities [4], for example, ACTH binds mainly to MC2R.

β-endorphin, on the other hand, is involved in pain processing as an inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system. Here it binds to opioid receptors, leading to an analgesic effect[5] [6].

CLIP is found in many areas of the brain, especially in nerve fibres, and has an important role in REM sleep, which in turn helps with the consolidation of memories [7].

The functions of β- and γ-LPH are still uncertain, although lipotropins are known for their role in lipolysis, mobilizing lipids for energy production, and they are important in haematopoiesis[8].

POMC, the Hypothalamus and Appetite Regulation

In mammals, alpha MSH is generally assumed to be the main POMC product involved in appetite regulation. Alpha MSH is a potent inhibitor of appetite (anorexigenic), acting on MC3-R and MC4-R in the arcuate nucleus. In POMC null mice, alpha-MSH was found to be the most potent anorexigenic signaller.[9]

Rodents do not express beta-MSH, but evidence has been found indicating an important role for beta-MSH in human appetite regulation. A study screening for mutations in the beta-MSH region of POMC found an increased incidence of the beta-MSH variant Try221Cys in obese subjects. The variant was shown to have altered binding and signalling through MC4-R.[10]

Desacetyl-alpha-MSH is a precursor for alpha-MSH and is widely distributed in the brain.[11] Although desacetyl-alpha-MSH displays a similar potency for receptor binding to alpha-MSH, it does not affect food intake except at extremely high doses.[12]

The arcuate nucleus (ARC) is found at the bottom of the hypothalamus and consists of several groupings of specific neurons (see Fig. 4). There are two main populations of neurons regulating appetite; those co-expressing POMC and cocaine and amphetamine regulated transcript (CART) and those co-expressing neuropeptide Y (NPY) and agouti related peptide (AgRP). The POMC/CART neurons form part of the satiety pathway in the arcuate nucleus and neurons co-expressing NPY and AgRP are part of orexigenic signalling.[17] AgRP acts as an inverse agonist at MC3-R and MC4-R, to help stimulate feeding.[17]

POMC/CART and NPY/AgRP neuron populations both express leptin receptors (LepRb). Leptin has opposing effects on each neuron population, activating the anorexigenic POMC neurons and inhibiting the orexigenic NPY/AgRP neurons, in the arcuate nucleus. Using transgenic mice expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP), two CNS regions expressing POMC in response to leptin were found: the arcuate nucleus and the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS).[13] Another study used transgenic mice with POMC-GFP expression and NYP-GFP expression, measuring the number of inhibitory and excitatory postsynaptic currents. Leptin deficient (ob/ob) mice were shown to have an increased excitation of NPY neurons and increased inhibition of POMC neurons compared to their wild-type littermates. Treatment with leptin lead to normalisation of the synaptic signals to wild-type levels.[18]

The full extent of the signalling between the neuron populations within the hypothalamus is not fully understood. It is thought that NPY neurons project to inhibit POMC expression, mediated through GABA.[14] Using electron microscopy, co-expression of GABA and NPY was confirmed at these nerve terminals.[13] Leptin also acts at the GABA nerve terminals to reduce the inhibition of POMC neurons.

Ghrelin mRNA has been shown to be expressed in the hyothalamus, using RT-PCR, but it is at present not clear whether the brain is a significant source of ghrelin. [19]There is some immunocytochemical evidence for ghrelin-containing axons in several hypothalamic nuclei, but at present it is thought that circulating ghrelin, secreted from the empty stomach, is the key appetite-regulating signal. Ghrelin was shown using fluorescent protein tagged NPY neurons, to increase release of NPY and AgRP, as well as increasing the GABA-mediated inhibition of POMC neurons. [15] Ghrelin is the endogenous ligand for the GHS-Receptor, which is dendely expressed in both the arcuate nucleus and the ventromedial nucleus.

There are five NPY receptors (Y1-Y5), which are also activated by the closely related peptide PYY. Using specific receptor agonists and measuring the effect on POMC mRNA levels, it was found that NPY down-regulates POMC expression through the Y2 receptor.[20] Interestingly, activation of a presynaptic Y2 autoreceptor suppresses NPY release. PYY3-36, a satiety signal released from the gut after a meal, acts as an agonist at the presynaptic Y2 receptors on the nerve terminals of NPY/AgRP/GABA neurons. This leads to suppression of NPY release and increased POMC release in the arcuate nucleus.[21]

POMC neurons involved in regulation of appetite are also found in the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS), with projections to the paraventricular nucleus and elsewhere. Cholecystokinin (CCK) is another satiety-inducing peptide from the gut. Its effects are mediated through CCK1 receptors and vagal afferents to the NTS. Both feeding and intraperitoneal injection of CCK8 resulted in increased c-fos expression in NTS POMC neurons.[22] The PVN contains oxytocin neurons that project to the NTS, and which are part of a feedback mechanism to stomach, closing off the gastric sphincter. In addition, magnocellular oxytocin neurons in both the supraoptic nucleus and the PVN have MC4 receptors, and in response to alpha MSH can release large amounts of oxytocin from their dendrites within the hypothalamus; the magnocellular neurones are also excited by gastric distension, and by systemic administration of CCK. The sites of action of dendritically released oxytocin are not clear, but the VMH is a likely target, as it has a very high density of oxytocin receptors.

Species Variation in the POMC Gene

Vertebrates

- ~ Agnatha – Lamprey

- ~ Gnathostomes

Osteichthyes

Sarcoptergii

POMC organisation among vertebrates in the Sarcoptergii class, consisting of the lobe-finned fish and the tetrapods, is very similar (Dores 2005). POMC in tetrapods, as described above, has three melanocortin sequences (γ-MSH, ACTH/α-MSH, and β-MSH) and a β-endorphin sequence. Lobe-finned fish, consisting of the lungfish and coelacanths (evolution of melanocortin systems in fish), also have three MSHs in their POMC, as well as one β-END. There are also many similarities between the POMC amino acid sequences of species within the Sarcoptergii class (Dores 2005). This highlights the fact that tetrapods and lobe-finned fish share a common POMC ancestor. However, mutations have been found in the core sequence of the γ-MSH region in POMC of one species of lobe-finned fish (the Australian lungfish). Similar mutations have also been found in some ray-finned fish, but not in other lobe-finned fish, or tetrapods (Dores at al 1999). This suggests that in the Australian lungfish, the γ-MSH sequence may be degenerating. This is similar to what has occurred in ray-finned fish (see below).

Actinopterygii

Like the Sarcoptergians, some ray-finned fish, such as the paddlefish and the sturgeon, have three MSH regions in their POMC sequences. However, mutations have been found in the core sequence of the γ-MSH sequence in these species, and at the proposed cleavage sites marking this region (Dores 1999, Kawauchi 2006), which probably means that it is non-functional and γ-MSH is not produced (Amemiya 1997) (Dores 2005). These mutations are similar to those found in the Australian lungfish, described above. All teleosts, a type of ray-finned fish, do not have the γ-MSH region at all. By sequencing the nucleotides of POMC mRNA, Kitahara et al noted its absence in salmon, and the same has been found in other teleosts (Dores 2005). This suggests the theory that the POMC gene in ray-finned fish accumulated mutations in the γ-MSH region over time, leading to its eventual deletion in teleosts (Dores 1999, Kawauchi 2006, Danielson 1999, Dores 2005).

Some ray-finned fish also express two or more POMC genes. For example, in the paddlefish, two POMC cDNA clones have been found (Danielson 1999). This is the same in sockeye salmon, rainbow trout, and sturgeon (takahashi 2006). However, in the flounder, three have been noted (Takahashi 2005). It has therefore been suggested that there has been duplication of the POMC gene in ray-finned fish (Danielson). Unlike in the lamprey, these genes are still all co-expressed in the pituitary (Dores 2005) and encode the same hormones as the tetrapod POMC. There are some differences between the two/ three POMC genes expressed however. For example, the β-MSH region is more highly conserved than the β-endorphin region in the paddlefish (Danielson) and POMC-C in the flounder has mutations in the β-endorphin sequence (Takahashi 2006). It has been suggested that in ray-finned fish, the degeneration of the γ-MSH sequence occurred after the duplication of the POMC gene (Danielson).

Chondrichthyes

Invertebrates

Summary/Conclusion

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Yang YK et al. (2003) Recent developments in our understanding of melanocortin system in the regulation of food intake. Obesity Rev 4:239-48 PMID 14649374

- ↑ Dores RM et al. (2005) Trends in the evolution of the proopiomelanocortin gene Gen Comp Endocrinol 142:81-93 PMID 15862552

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Raffin-Sanson et al. (2003) Proopiomelanocortin, a polypeptide precursor with multiple functions: from physiology to pathological conditions. Eur J Endocrinol 149:79–90 PMID 12887283.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Millington GW (2007) The role of proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurones in feeding behaviour Nutrition and Metabolism 4:18 PMID 17764572

- ↑ Kawauchi H et al. (2006) The dawn and evolution of hormones in the adenohypophysis Gen Comp Endocrinol 148:3-14 PMID 16356498.

- ↑ Dores RM et al. (2005) Trends in the evolution of the proopiomelanocortin gene Gen Comp Endocrinol 142:81-93 PMID 15862552.

- ↑ Grigoriev VV et al. (2009) Effect of corticotropin-Like intermediate lobe peptide on presynaptic and postsynaptic glutamate receptors and postsynaptic GABA Receptors in rat brain Bull Exp Biol Med 147:319-22 PMID 19529852.

- ↑ Halabe BA (2008) The role of lipotropins as hematopoietic factors and their potential therapeutic use Exp Hematol 36:752-4 PMID 18358591

- ↑ Tung YCL et al. (2007) A comparative study of the central effects of specific proopiomelanocortin (POMC)-derived melanocortin peptides on food intake and body weight in POMC null mice. Endocrinology 147:5940-5947 PMID 16959830

- ↑ Lee YS et al. (2006) A POMC variant implicates beta-melanocyte-stimulating hormone in the control of human energy balance Cell Metabolism 3:135-40 PMID 16459314

- ↑ Loh Y et al. (1980) MSH-like peptides in rat brain: identification and changes in level during development Biochem Biophys Res Commun 94:916-23 PMID 7396941

- ↑ Abbott et al. (2000). Investigation of the melanocyte stimulating hormones on food intake. Lack of evidence to support a role for the melanocortin-3-receptor Brain Res 869:203–10 PMID 10865075

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Cowley MA et al. (2001) Leptin activates anorexigenic POMC neurons through a neural network in the arcuate nucleus. Nature 441:480-4 PMID 11373681

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Cone RD (2005) Anatomy and regulation of the central melanocortin system Nature Neurosci 8:571-8 PMID 15856065

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Cowley MA et al. (2003) The distribution and mechanism of action of ghrelin in the CNS demonstrates a novel hypothalamic circuit regulating energy homeostasis Neuron 37:649-61 PMID 12597862

- ↑ Schwartz MW et al. (2000) Central nervous system control of food intake Nature 404:661-71 PMID 10766253

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Dhillo WS et al. (2002) Hypothalamic interactions between neuropeptide Y, agouti-related protein, cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript and alpha-melanocytestimulating hormone in vitro in male rats J Neuroendocrinol 14:725-30 PMID 12213133

- ↑ Pinto S et al. (2004) Rapid rewiring of arcuate nucleus feeding circuits by leptin. Science 304:110-5 PMID 15064421

- ↑ Kojima M et al. (1999) Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated from stomach Nature 402:656–60 PMID 10604470

- ↑ de Yebenes EG et al. (1995) Regulation of proopiomelanocortin gene expression by neuropeptide Y in the rat arcuate nucleus. Brain Research 674:112-116 PMID 7773678

- ↑ Batterham RL et al. (2002) Gut hormone PYY3-36 physiologically inhibits food intake. Nature 418:650-654 PMID 12167864

- ↑ Fan W et al. (2004) Cholecystokinin-mediated suppression of feeding involves the brainstem melanocortin system. Nature Neurosci 7(4):335-336 PMID 15034587