Scientific method: Difference between revisions

imported>Gareth Leng |

Pat Palmer (talk | contribs) (→The scientific method in practice: shortening first sentence slightly) |

||

| (486 intermediate revisions by 33 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | |||

< | <onlyinclude>{{Image|Hume.jpg|right|300px|Statue of [[David Hume]]. ''"Man is a reasonable being; and as such, receives from science his proper food and nourishment: But so narrow are the bounds of human understanding, that little satisfaction can be hoped for in this particular..."'' | ||

'' | Hume recognised clearly the difficulties in gaining a general understanding merely by accumulating observations.}} | ||

< | Scientists use a '''scientific method''' to investigate phenomena and acquire [[knowledge]]. They base the method on verifiable observation — i.e., on replicable [[empirical]] evidence rather than on pure logic or supposition — and on the [[reasoning|principles of reasoning]].<ref>[[Isaac Newton]] (1643-1727) [http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/newton-princ.html The Rules of Reasoning in Philosophy] Excerpts in: The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy. Source: [http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/modsbook.html Modern History Sourcebook]</ref> <ref>[http://www.archive.org/details/newtonspmathema00newtrich Full-Text: Newton's Principia: The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy (c1846), including BOOK III. RULES OF REASONING IN PHILOSOPHY]</ref> Scientists propose explanations — called [[hypothesis|hypotheses]] — for their observed phenomena, and perform experiments to determine whether the results accord with (support) the hypotheses or falsify them. They also formulate [[Theory#Science|theories]] that encompass whole domains of inquiry, and which bind supported hypotheses together into logically coherent wholes. They refer to theories sometimes as ‘models’, which often have a mathematical or computational basis.<ref name=leng2008>Leng G, MacGregor DJ. (2008) [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01722.x Mathematical Modelling in Neuroendocrinology]. ''Journal of Neuroendocrinology: From Molecular to Translational Neurobiology'' 20:713-718. | ||

*'''<u>Excerpt:</u>''' Our science is not only about facts, but also about explanations; rational accounts of phenomena, embedded in a framework of theory, which include a wide range of observations and which are predictive of behaviour in circumstances as yet untested. We all seek to explain the world of observations using a set of logically interacting components, and we all simplify by recognising that some observations are important while others can be reasonably neglected. Formulating such explanations mathematically is a natural ambition, because this ensures their logical consistency, and makes them open to structured analysis; it is a stringent test of their intellectual coherence.</ref> <ref name=mathscope>Citizendium Collaborators. (2009) [http://en.citizendium.org/wiki/Biology%27s_next_microscope:_Mathematics Biology’s Next Microscope: Mathematics.] Citizendium Free Online Encyclopedia. | |||

*'''<u>Excerpt:</u>''' Mathematics broadly interpreted is a more general microscope. It can reveal otherwise invisible worlds in all kinds of data, not only optical….Charles Darwin was right when he wrote that people with an understanding “of the great leading principles of mathematics... seem to have an extra sense”….Today’s biologists increasingly recognize that appropriate mathematics can help interpret any kind of data. In this sense, mathematics is biology’s next microscope, only better.</ref></onlyinclude> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

__TOC__ | |||

<br> | |||

==Components of the scientific method== | |||

{|align="center" cellpadding="10" style="background:lightgray; width:99%; border: 1px solid #aaa; margin:20px; font-family: Gill Sans MT; font-size: 93%;" | |||

|Science is said to proceed on two legs, one of theory (or, loosely, of deduction) and the other of observation and experiment (or induction). Its progress, however, is less often a commanding stride than a kind of halting stagger — more like the path of the wandering minstrel than the straight-ruled trajectory of a military marching band. The development of science is influenced by intellectual fashions, is frequently dependent upon the growth of technology, and in any case, seldom can be planned far in advance, since its destination is usually unknown. | |||

:—Timothy Ferris, ''Coming of Age in the Milky Way'' (1988)<ref>Ferris T. (1988) ''Coming of Age in the Milky Way''. New York: Morrow, ISBN 0688058892. | [http://books.google.com/books?id=k0vCHGD5Y00C&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q=trajectory&f=false Google Books preview, 2003 edition].</ref> | |||

|} | |||

{{-}} | |||

<!--<blockquote>''"Science is said to proceed on two legs, one of theory (or, loosely, of deduction) and the other of observation and experiment (or induction). Its progress, however, is less often a commanding stride than a kind of halting stagger — more like the path of the wandering minstrel than the straight-ruled trajectory of a military marching band. The development of science is influenced by intellectual fashions, is frequently dependent upon the growth of technology, and in any case, seldom can be planned far in advance, since its destination is usually unknown."'' Timothy Ferris, ''Coming of Age in the Milky Way'' (1988)</blockquote>--> | |||

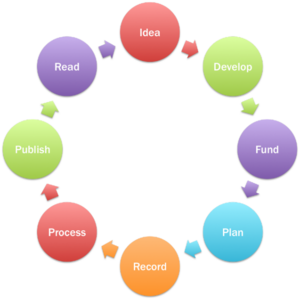

{{Image|Research cycle.png|right|300px|A simplified depiction of the cyclic nature of scientific research: An initial observation triggers an idea that is being developed into a hypothesis which — if funds, equipment and the necessary expertise are available — may lead to experimental data (or other forms of verifiable evidence) that can support or contradict the hypothesis or other existing theoretical descriptions of the system at hand, which in turn can trigger independent replication or falsification of this particular experiment if the relevant information are made available to other researchers. Traditionally, this publication step would be achieved solely via articles in toll-access [[scientific journal]]s but initiatives like [[Open Access]], [[Open Source]] and [[Open Data]] are increasingly making all these individual steps public, which is facilitated through the use of [[Web 2.0]] technologies in what has come to be called [[Science 2.0]].}} | |||

Generally accepted components of a scientific method are: | |||

* ''Observation.''<ref> According to the [[logical positivist]] philosopher [[Rudolf Carnap]], philosophers and scientists use the term 'observable' in different ways. To philosophers, 'observable' applies to properties that are directly perceived by the senses, such as "blue", "hard" and "hot". To scientists, the word includes anything that can be measured relatively simply and directly. Carnap R (1966)[http://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/ge/carnap.htm Theories and Nonobservables] from ''Philosophical Foundations of Physics'' Basic Books, ASIN B0000CN9NI </ref> Observations do not just await discovery, rather they often result from active exploration, questioning, sharing ideas and information among scientists, thinking creatively. Moreover, according to most current views, observations do not come into view wholly independently of some predetermined or preconceived theory; scientists struggle to keep their preconceptions and presuppositions out of the picture.<ref>[http://www.galilean-library.org/theory.html Theory-ladenness] by Paul Newall at The Galilean Library</ref><ref>Darwin CR. (1861) [http://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/darwinletters/calendar/entry-3257.html Letter 3257 — Darwin, C. R. to Fawcett, Henry, 18 Sept (1861)] | |||

:*'''Note:''' [[Charles Darwin|Darwin]] understood the point. Excerpt from the letter to Fawcett: “About thirty years ago there was much talk that geologists ought only to observe and not theorise; and I well remember some one saying that at this rate a man might as well go into a gravel-pit and count the pebbles and describe the colours. ''How odd it is that anyone should not see that all observation must be for or against some view if it is to be of any service!”''” <nowiki>[</nowiki>Emphasis added<nowiki>]</nowiki></ref> Sometimes "believing is seeing". | |||

*''Hypothesis.'' Hypotheses are general statements, formulated as plausible conjectures to explain existing observations and predict future observations. | |||

*''Experiment.''<ref> For [[Aristotle]], science was the product of reason applied to careful observations; [[Galileo Galilei]] by contrast used experiments as a way to interrogate Nature.</ref> An experiment is a procedure carried out under controlled conditions to discover an unknown effect; to provide confirming or disconforming evidence for a hypothesis, often based on whether a prediction of the hypothesis ensues; or, to illustrate an accepted theory. Not all areas of science involve direct experimentation; as an example for [[data-driven research]], the [[Human Genome Project]] largely involved (highly technical) interpretation of gene sequences, but the data were obtained by experimental investigation. | |||

* ''Theory.'' A [[Theoretical biology|theory]] incorporates a set of supported hypotheses into a logical framework that overall explains the phenomenon studied. Not all of the statements of a theory are necessarily open to experimental testing, but many are expected to be for a theory to be considered scientific. The scientific method usually involves further testing of its accepted satisfactory overall explanation of a phenomenon, as natural phenomena usually have more observable features than the theorist knows at the time the theory hatches. A good theory will make accurate predictions about the behavioral aspects of the phenomenon studied, suggesting experiments to test its overall explanatory power. | |||

* ''Prediction.'' A prediction is a logical deduction from a hypothesis (or theory) by which the hypothesis (or theory) can be tested experimentally. | |||

* ''Testing.'' A 'test' of a hypothesis is an experiment, the results of which might falsify (disprove) the hypothesis; if the test does not falsify the hypothesis, the test is said to support ('confirm') the hypothesis. The same holds for testing theories. | |||

* ''Causal explanation.'' Satisfactory explanations are often regarded as those that establish a cause-effect relationship. However, many scientists argue that concepts of causality are not obligatory to science, but are well-defined only under particular conditions.<ref>Dowe, Phil. (Fall 2008 Edition) [http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2008/entries/causation-process/ Causal Processes.] ''The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Edward N. Zalta.</ref> <ref>Woodward, James. (Spring 2009 Edition) [http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2009/entries/scientific-explanation/ Scientific Explanation.] ''The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Edward N. Zalta (ed.).</ref> | |||

* ''Skeptical open mindedness.'' Progress in extending existing theoretical frameworks is made possible by a scientific culture that encourages challenges to existing theory, while also demanding that far-reaching conjectures are validated by exceptional evidence.<ref>'''<u>Note:</u>''' Regarding 'skeptical open mindedness', to paraphrase space engineer, James Oberg, open mindedness confers virtue unless it so opens the mind that one's brains fall out. (Cited by Carl Sagan, in ''The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark.'' Ballantine Books: New York, 1997. Preview Sagan's book at Google Books [http://books.google.com/books?id=q_Fp3tjPnkwC here].) | |||

*'''<u>Excerpt:</u>''' Keeping an open mind is a virtue — but, as the space engineer James Oberg once said, not so open that your brains fall out. Of course we must be willing to change our minds when warranted by new evidence. But the evidence must be strong. Not all claims to knowledge have equal merit. (Page 187)</ref> | |||

==Philosophy of scientific methods== | |||

[http://www. | <blockquote>''If the purpose of scientific methodology is to prescribe or expound a system of enquiry or even a code of practice for scientific behavior, then scientists seem to be able to get on very well without it. Most scientists receive no tuition in scientific method, but those who have been instructed perform no better as scientists than those who have not. Of what other branch of learning can it be said that it gives its proficients no advantage; that it need not be taught or, if taught, need not be learned?'' [[Peter Medawar]]<ref>Medawar P (1982) ''Pluto's Republic'', Oxford University Press ISBN 0192830392; read [http://www.the-rathouse.com/Medawar_PlutoRepublic.html a review here]</ref></blockquote> | ||

{|align="left" cellpadding="10" style="background:lightgray; width:25%; border: 1px solid #aaa; margin:20px; font-size: 93%; font-family: Gill Sans MT;" | |||

| Evolutionary processes and, in general, scientific explanations of the world are often in contrast with the immediate and simple explanations that our brain gives of reality (e.g. the sun seems to turn around the earth, the earth seems to be flat), and are influenced by what Francis Bacon called "idola"[<ref name=hall>Hall MP. [http://www.sirbacon.org/links/4idols.htm The Four Idols of Francis Bacon: The New Instrument of Knowledge]. | |||

*<font face="Gill Sans MT">"In the Novum Organum (the new instrumentality for the acquisition of knowledge) Francis Bacon classified the intellectual fallacies of his time under four headings which he called idols. He distinguished them as idols of the Tribe, idols of the Cave, idols of the Marketplace and idols of the Theater…An idol is an image, in this case held in the mind, which receives veneration but is without substance in itself. Bacon did not regard idols as symbols, but rather as fixations."</font></ref>] (false notions or tendencies which distort the truth [<ref>Fantini F. (2005) Didattica dell'evoluzione. In Evoluzione tra ricerca e didattica, XIV – Special number Edited by: Associazione Nazionale Insegnanti di Scienze Naturali. Agnano Pisano: Stamperia Editoriale Pisana; 2005:203-209.</ref>]).<ref name=guidetti>Guidetti R, Baraldi L, Calzolai C, Pini L, Veronesi P, Pederzoli A. (2007) [http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/7/S2/S Fantastic animals as an experimental model to teach animal adaptation]. ''BMC Evolutionary Biology'' 7(Suppl 2):S13 doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-S2-S13.</ref> | |||

|} | |||

Non-scientists often represent science as a dry, mechanical activity, involving accumulating large numbers of facts, whether by simple observations or by technologically ingenious means. Indeed, this ''is'' an important part of science, and technological advances in our ability to interrogate the world have played an essential part in the advance of science: we need only consider how the [[light microscope]], then the [[electron microscope]], and now the [[scanning tunneling microscope]]<ref>[http://nobelprize.org/educational_games/physics/microscopes/scanning/index.html Scanning Tunneling Microscope] at the Nobel Foundation's website</ref> and [[two-photon laser scanning confocal microscopy]] have radically changed our understanding of the world. However, observations, things that we might sometimes call 'facts', are just the beginning. Thus, according to [[Charles Darwin]] (1809-1882), "science consists in grouping facts so that general laws or conclusions may be drawn from them."<ref> From the autobiography of Charles Darwin, [http://www.worldwideschool.org/library/books/hst/european/TheAutobiographyofCharlesDarwin/chap2.html available online].</ref> | |||

But what exactly do we mean by ‘facts’? We sometimes disagree about the ‘facts’ we see around us, and some things in the world are at odds with our understanding. How much can we trust our senses to allow us to believe what we see? How do scientists ‘group’ facts? How do they choose which facts to attend to, and is it possible to do this in an objective way? And having done this, how do they draw any broader conclusions? Most importantly, how can we ever know ''more'' than we observe directly? We live in a world that is not directly understandable: we all ''interpret'' everything that we see and hear and feel, and to make sense of what our senses tell us we need to construct ''explanations'', or formulate theories. Our explanations identify some things as important and other things as irrelevant; they lead us to pay attention to some things and not others, and they lead us to expect some things to happen and not others — they lead, in other words, to predictions. | |||

Nothing about this is unique to science, but scientists attempt to harness these universal elements of reasoning in a consistent, systematic and rigorous manner, and in a way that minimizes bias. What we call the 'scientific method' is an account of how scientists gather and report observations in ways that will be understood by other scientists and accepted as valid evidence, and how they construct explanations that are consistent with the world, and that can withstand logical and experimental scrutiny and provide the foundations for further increases in understanding. | |||

For many, the scientific approach begins with an attitude of skepticism — a willingness to question accepted beliefs, expressed by [[René Descartes]] in 1637 as a determination "never to accept anything for true which I did not clearly know to be such". The English philosopher [[Francis Bacon]] (1561-1626), often described as the pioneer of the modern scientific method, proposed that scientists should "empty their minds" of self-evident truths and, by observation and experimentation, should draw general conclusions by a process known as [[induction (philosophy)|induction]].<ref> [[Francis Bacon|Bacon, Francis]] (1620) ''[[Novum Organum]] (The New Organon)''</ref> Bacon described many of the commonly accepted principles of scientific method, but recognised that to interpret nature, something more than observation and reason is needed: | |||

:''...the universe to the eye of the human understanding is framed like a labyrinth, presenting as it does on every side so many ambiguities of way, such deceitful resemblances of objects and signs, natures so irregular in their lines and so knotted and entangled. ... No excellence of wit, no repetition of chance experiments, can overcome such difficulties as these. Our steps must be guided by a clue...''<ref>from ''Preface to The Great Instauration; 4.18'' quoted in Pesic P (2000) The Clue to the labyrinth: Francis Bacon and the decryption of nature [http://www.sirbacon.org/pesic.htm ''Cryptologia'']. Francis Bacon should not be confused with [[Roger Bacon]] (ca 1214-1294), a Franciscan friar who also has claims to be a pioneer of observation and experiment, and who was imprisoned when his work challenged the dogma of the Church.</ref> | |||

The 'something more' that is needed comes from imagination and intuition, guided by reason and understanding. Scientists make ambitious 'leaps' to envisage possible explanations that make sense of what we see. Classically, the scientific method has thus been broken into basic facets that start with ''observations'' of nature and how it behaves and then making a ''prediction'' about how it might behave under different circumstances. Scientists propose a ''hypothesis'' and, by ''experiments'' test it by eliminating any plausible alternatives in a process of ''falsification''. Other scientists join in the process of hypothesis testing, while at the same time developing new hypotheses that seek to explain more and more, thereby building a foundation of knowledge that they call science. However all of this is guided by theory — a framework of accepted knowledge and understanding that guides our choice of questions to ask, guides our choices about how to go about answering those question, and guides our interpretation of the results of those experiments. This theoretical framework that captures what we think we already know is what provides the clues to know more. When we are mistaken in what we think we know, however, everything that we build on those foundations becomes unsafe, and when a new theory emerges much of what we thought we had learned has to be interpreted afresh. New theories are therefore embraced only with reluctance, only as a last resort, because of the inevitable disruption that entails. | |||

==Hypotheses== | |||

<blockquote>''The man of science must work with method. Science is built up of facts, as a house is built of stones; but an accumulation of facts is no more a science than a heap of stones is a house. ''[[Henri Poincaré]], mathematician and philosopher (1854-1912)<ref> Henri Poincaré (1905). [http://www.brocku.ca/MeadProject/Poincare/Poincare_1905_toc.html Science and Hypothesis]. London: Walter Scott Publishing.</ref></blockquote> | |||

The philosopher [[Karl Popper]] (1902-1994), in ''The Logic of Scientific Discovery'' <ref> Popper K (1959) ''The Logic of Scientific Discovery'' (Translation of ''Logik der Forschung''). The Nobel prize winner Sir Peter Medawar called this book "one of the most important documents of the 20th century" </ref> argued that the 'Baconian' process of induction — of gathering facts, considering them, and inferring general laws — is logically unsound, as many mutually inconsistent hypotheses might be consistent with any given facts.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/induction-problem/ |title=The Problem of Induction (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) |accessdate=2007-11-16 |author=Vickers, J |date=2006 |publisher=Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy}}</ref> Rather, Popper argued that the good scientist begins with a bold speculation, a hypothesis, from which he logically deduces predictions that can be tested by experiments. Experiments are not designed to confirm or verify the hypothesis, quite the contrary, they are designed to ''test'' the hypothesis, by attempting to disprove it. He argued that this 'hypothetico-deductive' method was the only sound way by which science makes progress, and concluded that for a proposition to be considered scientific, it must, at least in principle, be possible to make an observation that would show it to be false. Otherwise, the proposition has, as Popper put it, no connection with the real world. | |||

==Responses to Popper: Thomas Kuhn and the Science Wars== | |||

Popper's views were in marked contrast to those of his contemporary, [[Thomas Kuhn]] (1922-1996). Kuhn's own book ''The Structure of Scientific Revolutions'' was as influential as Popper's, but its message was very different. Kuhn analysed 'scientific revolutions' — times in the history of science when one dominant theory was replaced by another, such as the replacement of [[Ptolemy]]'s geocentric model of the Universe with the [[Copernicus| Copernican]] heliocentric model, and the replacement of Newtonian laws of motion with [[Albert Einstein|Einstein]]'s theory of [[Relativity]]. | |||

While in many respects, Popper seemed to be making flat assertions about 'good science', Kuhn attempted to work as a sociologist, and to report what scientists actually did. At least initially in his career, he believed in some form of scientific progress. | |||

Kuhn divided scientific development (to avoid the word 'progress') into two phases, times of [[normal science]] and times of [[paradigm shift]]. A [[paradigm]] is a logically consistent set of ideas that guides and constrains the work that scientists do. Scientific research conducted in accordance with a dominant paradigm is called ''normal science''. A ''paradigm shift'' occurs when a radical change occurs in the fundamental beliefs scientists hold about their field of study. | |||

Kuhn concluded that falsifiability had played almost no role in scientific revolutions. He argued that scientists working in a field resist the alternative interpretations of 'outsiders', and tenaciously defend their world view by continually elaborating their shared theory; "normal science often suppresses fundamental novelties because they are necessarily subversive of its basic commitments". | |||

<ref> | According to Kuhn, most progress is made in a scientific field when one theory is dominant. Progress occurs by the "puzzle solving" of scientists who are not trying to challenge the accepted theory, but are trying to extend its scope and explanatory power, bringing theory and fact into closer agreement by a "strenuous and devoted attempt to force nature into the conceptual boxes supplied by professional education".<ref> | ||

Kuhn TS (1961) The Function of Measurement in Modern Physical Science ''ISIS'' 52:161–193 | |||

* Kuhn TS (1962)''The Structure of Scientific Revolutions'' | * Kuhn TS (1962)''The Structure of Scientific Revolutions'' University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. 2nd edition 1970, 3rd edition 1996 | ||

* Kuhn TS (1977) ''The Essential Tension, Selected Studies in Scientific Tradition and Change'' | * Kuhn TS (1977) ''The Essential Tension, Selected Studies in Scientific Tradition and Change'' University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL | ||

*A [http://www.des.emory.edu/mfp/kuhnsyn.html Synopsis] from the original by Professor Frank Pajares, From the Philosopher's Web Magazine | |||

*Moloney DP (2000) ''First Things'' '''101'''[http://www.firstthings.com/ftissues/ft0003/articles/kuhn.html 53-5]</ref> | |||

After the publication of 'The Structure of Scientific Revolutions' in 1962, Kuhn's revolution expanded. In the 1960s and 1970s, the academy (particularly in America) was in ferment. The development of radical and Marxist theory combined with political frustrations, and gave rise to a generation of academics who were deeply dissatisfied with the central narratives of American life, including scientific progress. Many of these academics latched on to Kuhn's ideas (and sometimes just his slogans) as a natural fit with their own ideas. | |||

This frustration with mainstream science took a series of forms. In the 1970s, the conflict began with early skirmishes about [[intelligence testing]] and the small-scale, though ferocious, battle over [[sociobiology]]. (It is worth noting that the sociobiology affair remained primarily a dispute within science) The partisans of the sociobiology debate continued their struggle into the 1980s. In the 1990s, scholars from the humanities and social sciences launched an assault on the central beliefs of science in what came to be known, somewhat hyperbolically, as the [[science wars]]. | |||

==Theories== | |||

{|align="right" cellpadding="10" style="background:lightgray; width:35%; border: 1px solid #aaa; margin:20px; font-size: 93%; font-family: Gill Sans MT;" | |||

|The three [[Laws of Thermodynamics]] can be expressed in many different ways<ref>these examples are given as on a [http://www.grc.nasa.gov/WWW/K-12/airplane/thermo.html NASA web site]</ref> | |||

|- | |||

|[[Zeroeth Law]]: When two objects are separately in thermodynamic equilibrium with a third object, they are in equilibrium with each other. | |||

|- | |||

||[[First Law]] (Principle of Conservation of Energy): Between any two equilibrium states, the change in internal energy is equal to the difference of the heat transfer into the system and work done by the system. | |||

|- | |||

||[[Second Law]] (Carnot's Principle): A natural process that starts in one equilibrium state and ends in another will go in a direction that causes the [[entropy (thermodynamics)|entropy]] of the system plus the environment to increase for an irreversible process and to remain constant for a reversible process. | |||

|} | |||

A '''scientific theory'''<ref>In science, the term "theory" indicates a logically connected set of hypotheses supported by a significant body of evidence. In daily life the term is used as in "that's just your theory", a hunch which may or may not be correct. This difference in meaning leads to miscommunication between scientists and laypersons, see: Helen Quinn, ''[http://ptonline.aip.org/getpdf/servlet/GetPDFServlet?filetype=pdf&id=PHTOAD000060000001000008000001&idtype=cvips Belief and knowledge—a plea about language]'', Physics Today, January 2007. </ref> is an overarching world view in an area of science. A theory may include statements of general scientific laws, such as the [[Laws of Thermodynamics]], it has a logical structure and includes axioms and defined concepts, and broadly it seeks to provide a coherent explanation of a large body of observations, and to bind these together with a set of related hypotheses. Theories are a necessary part of science because they determine a common language by which scientists in a field can communicate — communication of ideas depends upon scientists sharing key assumptions and using a common terminology. A particular theory is adopted by a scientific community for complex reasons; theories are preferred when they are successful in explaining a wide body of observations, but also when they are elegant, aesthetically satisfying in a way that is hard to define. This is sometimes expressed as a preference for simple, clear explanations. In the 14th century, the English logician and Franciscan friar [[William of Ockham]] formulated the 'law of parsimony', commonly known as '[[Ockham's razor]]' — "entities should not be multiplied more than is needed" (in Latin, ''entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitatem''). | |||

An example of a current theory is the Theory of [[Evolution]] by [[natural selection|Natural Selection]]. This seeks to explain the characteristics of all currently living organisms as the products of evolution, acting mainly by natural selection of organisms for reproductive success. The foundation of this theory is that, within any single species, individuals differ in the exact composition of their genes. These differences arise because of spontaneous random mutations in the genes, and because, in sexually reproducing organisms, every organism will inherit a different combination of genes from their parents, and because, independently of sexuality, there are mechanisms for generating novel genes by rearrangement of existing genes, and mechanisms for changing the way a gene functions. These processes for generating inheritable novelty produce differences in the traits of the individual organisms which can mean that some individuals are more likely to survive and reproduce than others, so the particular genes that they carry are more likely to be propagated in the next generation. Over time, beneficial genes — those that confer advantages to the individuals that carry them — will accumulate in a population, and maladaptive genes will be eliminated. Accordingly, over many generations, the characteristics of a population will change — the population will evolve. Eventually, in some circumstances, such as when a population is geographically isolated and subject to different environmental challenges, this can give rise to a new species. | |||

It is not in the scope of this article to explain this theory fully or to defend it, but here we simply note a few features of this theory that are common to all theories. First, the theory explains a very large body of knowledge — the origin of the characteristics of all living things. Second, the theory involves presumptions: in this case, one presumption is that no intelligent creator directs the process of evolution. The theory cannot contradict the thesis that there is such an intelligent creator, it only declares that it is not necessary to invoke the existence of an intelligent creator to explain evolution. The theory does give an explanation for how living systems emerged from the non-living world. Third, the theory gives rise to hypotheses and to predictions. One hypothesis is that all life arises from common ancestors, and a prediction from this is that the genes of different species will show evidence for this, in that the genes that characterise different species will differ by a degree that is related to the time when the fossil record tells us that the species diverged. Fourth, the theory has undergone continual development and embellishment since it was first articulated by Charles Darwin, indeed the theory was proposed when virtually nothing was known of genes. | |||

The Theory of [[natural selection]] is generally regarded as one of the 'cornerstones' of modern biology, but in a strict sense it is difficult to see it as falsifiable. It is accepted less because of the weight of experimental evidence, or because of its success in withstanding attempted disproof, but because of aesthetic considerations. In its essence it is seductively simple, and the force of its logic makes it seem self evidently true to contemporary biologists; it has a sweeping power to explain many diverse things, and it has succeeded, despite its simplicity, in stimulating many important ideas about the mechanisms underlying genes, their functions and their mechanisms of inheritance. | |||

To say that the Theory is generally accepted is not to say that biologists are fully in agreement with each other; they are not, there is considerable debate and disagreement about many aspects of the Theory, especially about which of the many mechanisms of natural selection are most important. There are also alternatives, notably the Theory of [[Intelligent Design]]. This theory is based on the conclusion of its proponents that natural selection alone is incapable of explaining the evolution of highly complex organisms, and it postulates that some intelligence must have been involved in their design. The theory of Intelligent Design is accepted by very few biologists; most do not agree that the theory of natural selection cannot account for the complexity of living creatures, and so regard the concept of an intelligent designer as in breach of Ockham's razor. | |||

For Popper, no theory can ever be shown to be true - a theory may be corroborated by evidence, but can never be verified. He regarded the old scientific ideal of certain, demonstrable knowledge as illusory: that we can be certain about our faith, but scientific statements are forever in doubt. It is not possession of knowledge that makes the "man of science", but the "persistent and reckless ''quest'' for truth." In his words: | |||

<blockquote>''Science does not rest upon solid bedrock. The bold structure of its theories rises, as it were, above a swamp. It is like a building erected on piles...if we stop driving the piles deeper, it is not because we have reached firm ground. We simply stop when we are satisfied that the piles are firm enough to carry the structure, at least for the time being.'' (Popper, K (1959) ''The Logic of Scientific Discovery'')</blockquote> | |||

==The scientific method in practice== | ==The scientific method in practice== | ||

The UK Research Charity | While scientists disagree among themselves and between themselves about whether there is a general "scientific method" and if so exactly what it involves, in any given field there are always some practices that are accepted as scientific good practice and others that are not. When scientists give expert evidence in Courts of Law, their evidence is given particular weight, reflecting the respect that is given to good scientific practice. In 1993, in the [[Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals]] decision, the U.S. Supreme Court accorded a special status to 'The Scientific Method', in ruling that "… to qualify as 'scientific knowledge' an inference or assertion must be derived by the scientific method. Proposed testimony must be supported by appropriate validation - i.e., 'good grounds', based on what is known." The Court also stated that "A new theory or explanation must generally survive a period of testing, review, and refinement before achieving scientific acceptance. This process does not merely reflect the scientific method, it is the scientific method."<ref> [http://straylight.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/92-102.ZS.html Text of the opinion, LII, Cornell University]; [http://www.defendingscience.org/upload/Daubert-The-Most-Influential-Supreme-Court-Decision-You-ve-Never-Heard-Of-2003.pdf Daubert-The Most Influential Supreme Court Decision You've Never Heard of]</ref> | ||

<blockquote> ''[Scientists] start by making an educated guess about what they think the answer might be, based on all the available evidence they have. This is known as forming an hypothesis. | |||

The UK Research Charity ''Cancer Research UK'' gives an outline of the scientific method, as practised by their scientists<ref name=CR-UK>[http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerandresearch/aboutcancerresearch/thescientificmethod/ Science fact or fiction?], from Cancer Research UK</ref>. | |||

''Researchers carry out carefully designed studies, often known as experiments, to test their hypothesis. They collect and record detailed information from the studies. They look carefully at the results to work out if their hypothesis is right or wrong…'' </blockquote> | |||

===Hypotheses=== | |||

{|align="right" cellpadding="10" style="background:lightgray; width:30%; border: 1px solid #aaa; margin:20px; font-size: 93%; font-family: Gill Sans MT;" | |||

|It is always safe and philosophic to distinguish, as much as is in our power, fact from theory; the experience of past ages is sufficient to show us the wisdom of such a course; and considering the constant tendency of the mind to rest on an assumption, and, when it answers every present purpose, to forget that it is an assumption, we ought to remember that it, in such cases, becomes a prejudice, and inevitably interferes, more or less, with a clear-sighted judgment. I cannot doubt but that he who, as a wise philosopher, has most power of penetrating the secrets of nature, and guessing by hypothesis at her mode of working, will also be most careful, for his own safe progress and that of others, to distinguish that knowledge which consists of assumption, by which I mean theory and hypothesis, from that which is the knowledge of facts and laws; never raising the former to the dignity or authority of the latter, nor confusing the latter more than is inevitable with the former. | |||

:::—Michael Faraday<ref name=fara1844v2>Faraday M. (1844) ''Experimental Researches in Electricity''. Volume 2. Richard and John Edward Taylor, printers and publishers to the University of London. | [http://books.google.com/books?id=2oSFAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false Google Book full-text]. | |||

*"It is always safe and philosophic to distinguish...", pp. 285-286.</ref> | |||

|} | |||

<blockquote> ''[Scientists] start by making an educated guess about what they think the answer might be, based on all the available evidence they have. This is known as forming an hypothesis.''<ref>This quote and the ones that follow are from the ''Cancer Research UK'' outline.</ref></blockquote> | |||

A ''hypothesis'' is a proposed explanation of a phenomenon. It may be an “inspired guess”, a “bold speculation”, embedded in current understanding yet going beyond that to assert something that we do not know for sure as a way of explaining something not otherwise accounted for. Most importantly, a scientific hypothesis is something that has ''consequences'', it leads to predictions and these can be tested by experiments. If the predictions prove wrong, the hypothesis is discarded, otherwise it is put to further test. If it resists determined attempts to disprove it, then it might come to be accepted, at least for the moment, as 'true'. | |||

Scientists use many different means to generate hypotheses, including their own creative imagination, ideas from other fields, and by [[induction (philosophy)|induction]]. [[Charles Sanders Peirce]] (1839-1914) described the incipient stages of [[inquiry]], instigated by the "irritation of doubt" to venture a plausible guess, as ''[[Inquiry#Abduction|abductive reasoning]]'' <ref>[http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/peirce/ Charles Sanders Peirce] entry at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy</ref>. The history of science is full of stories of scientists claiming a "flash of inspiration" which motivated them. One of the best known is from the chemist [[August Kekulé]] (1829-1896), who proposed that structure of molecules followed particular rules. Kekulé recounted that the structure of benzene came to him in a dream, in which rows of atoms wound like serpents before him; one of the serpents seized its own tail: "the form whirled mockingly before my eyes. I came awake like a flash of lightning. This time also I spent the remainder of the night working out the consequences of the hypothesis".<ref>cited in Bargar RR, Duncan JK (1982) Cultivating creative endeavor in doctoral research ''J Higher Educ 53:1-31 [http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.2307/1981536 doi]</ref> | |||

===Experiments and observations=== | |||

<blockquote>''Researchers carry out carefully designed studies, often known as experiments, to test their hypothesis. They collect and record detailed information from the studies. They look carefully at the results to work out if their hypothesis is right or wrong…'' </blockquote> | |||

An ''experiment'' is a procedure carried out under controlled conditions to gain new information or better understanding. Not all science involves experimentation; for example the human genome project largely involves (highly technical) interpretation of gene sequences, but the data were obtained by experimental investigation. Equally, not all experiments are designed to test hypotheses; some extend our knowledge by making more detailed observations of known phenomena, or by exploring new or unexplained phenomena more fully. | |||

Between 1907 and 1917, the theoretical physicist [[Albert Einstein]] (1879-1955) developed the [[General theory of relativity]], which, amongst other things, explains gravitation as a manifestation of curvature of space and time. Several predictions can be derived from Einstein's theory of [[General Relativity]], and one prediction was that light will appear to 'bend' in a gravitational field by an amount that depends on the strength of the field. [[Arthur Eddington]] (1882-1994) devised experiments to test this prediction; his observations, made during a solar eclipse in 1919, supported General Relativity and showed the restrictions in applicability of the accepted theory of gravitation, credited to [[Isaac Newton]] (1643-1727). | |||

[[Werner Heisenberg]] (1901-1976) was one of the physicists responsible for developing the theory of [[quantum mechanics]] (which so far resisted logical unification with general relativity). In a quote that he attributed to Albert Einstein, he stressed how observations depend upon the theories that are held at the time they are made <ref>[[Werner Heisenberg|Heisenberg, Werner]] (1971) ''Physics and Beyond, Encounters and Conversations'', A.J. Pomerans (trans.), Harper and Row, New York, NY pp.63–64</ref> "The phenomenon under observation produces certain events in our measuring apparatus. As a result, further processes take place in the apparatus, which eventually and by complicated paths produce sense impressions and help us to fix the effects in our consciousness. Along this whole path—from the phenomenon to its fixation in our consciousness—we must be able to tell how nature functions, must know the natural laws at least in practical terms, before we can claim to have observed anything at all. Only theory, that is, knowledge of natural laws, enables us to deduce the underlying phenomena from our sense impressions." | |||

For Karl Popper, theory was profoundly important in science; a theory encompasses the preconceptions by which the world is viewed, and defines what we choose to study, and how we study it and understand it. He recognised that theories are not discarded lightly, and a theory might be retained long after it has been shown to be inconsistent with known facts ([[anomalies]]). However, the recognition of anomalies drives scientists to adjust the theory, and if the anomalies continue to accumulate, will drive them to develop alternative theories. Popper proposed that a theory should be judged by the extent to which it inspires testable hypotheses. While theories always contain many elements that are not falsifiable, Popper argued that these should be as few as possible. However, scientists also seek theories that are "elegant"; a theory should yield clear, simple explanations of complex phenomena, that are intellectually satisfying in being logically coherent, rich in content, and involving no miracles or other supernatural devices. | |||

===Peer review=== | ===Peer review=== | ||

<blockquote> ''…Once they have completed their study, the researchers write up their results and conclusions. And they try to publish them as a paper in a scientific journal. Before the work can be published, it must be checked by a number of independent researchers who are experts in a relevant field. This process is called ‘peer review’, and involves scrutinising the research to see if there are any flaws that invalidate the results…'' </blockquote> | <blockquote> ''…Once they have completed their study, the researchers write up their results and conclusions. And they try to publish them as a paper in a scientific journal. Before the work can be published, it must be checked by a number of independent researchers who are experts in a relevant field. This process is called ‘peer review’, and involves scrutinising the research to see if there are any flaws that invalidate the results…'' </blockquote> | ||

Manuscripts submitted for publication in scientific journals are normally sent by the editor to (usually one to three) | The main way of disseminating scientific information is through the peer-reviewed scientific literature. This is a vast array of academic journals that was once mainly restricted to the libraries of Universities and research institutes, but these are now mostly available on-line through the internet, and often they are freely available. There are many thousands of these journals, some of which are managed and owned by scientific societies, others by commercial publishers. The better scientific journals publish just a small proportion of the manuscripts submitted to them, and only after a process of peer review and revision. An article published in the peer-reviewed literature that describes the outcome of a series of experiments is known as a 'scientific paper'. Over their careers, many scientists may publish more than a hundred such papers, but even for the most successful scientists very few of their papers have a major, lasting influence. Some scientists have achieved wide acclaim despite publishing very few papers, because of the exceptional importance of those few. One measure of the influence of a paper is how often it is 'cited' — referenced in other scientific papers. As most scientific papers include references to about 30 other papers, an average paper will eventually accrue about 30 'citations'. [[Frederick Sanger]], twice winner of the [[Nobel Prize for Chemistry]] (1958 and 1980)<ref>[http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1958/ 1958 Nobel Prize for Chemistry] and [http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1980/ 1980 Nobel Prize for Chemistry])</ref> published about 70 papers in his whole career; 30 of these have been cited more than 100 times each, and four of them more than 1000 times each. | ||

Manuscripts submitted for publication in scientific journals are normally sent by the editor to (usually one to three) other scientists for evaluation. These 'expert referees' advise the editor about the suitability of the paper for publication in the journal. They also report, usually anonymously, on its strengths and weaknesses, pointing out any errors or omissions that they noticed and offering suggestions for how the paper might be improved by revision or by further experiments. With this advice, the editor might reject the paper or decide that it might be acceptable if appropriately revised. | |||

Peer review has been widely adopted by the scientific community, but has weaknesses. It is easier to publish data that are consistent with a generally accepted theory than data that contradict it. This helps to ensure the stability of the accepted theory, but also means that the appearance of the extent to which a current theory is supported by evidence might be misleading — boosted by a poorly scrutinised supportive work while insulated from criticism. The biologist Lynn Margulis encountered great difficulty in publishing her theory that the eukaryotic cell is a symbiotic union of primitive prokaryotic cells. In 1966, she wrote a theoretical paper entitled ''The Origin of Mitosing Cells''; it was "rejected by about fifteen scientific journals," as Margulis recalled. Finally accepted by ''The Journal of Theoretical Biology'', it is now considered a landmark in modern [[endosymbiotic theory]].<ref>Sagan L (1967) On the origin of mitosing cells" ''J. Theor Biol'' '''14''':255-74 [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=11541392&dopt=Citation Abstract]</ref> In 1995, [[Richard Dawkins]] said, "I greatly admire Lynn Margulis's sheer courage and stamina in sticking by the endosymbiosis theory, and carrying it through from being an unorthodoxy to an orthodoxy." <ref>John Brockman, [http://www.edge.org/documents/ThirdCulture/n-Ch.7.html ''The Third Culture''], New York: Touchstone 1995, 144</ref> | |||

To the defense of the possible conservatism of reviewers, it must be remarked that they must trust at face value the experimental data that are in the manuscript before them. They cannot repeat the experiments and verify their outcome—they lack the time and often the possibility. All a reviewer can do is decide whether experimental data look "reasonable", which implies a judgment about the plausibility of the data in the light of the ruling paradigm. There are some famous cases of fraud that took years before unveiling, mainly because the fraud took care that his/her faked results looked "reasonable". Conversely, experimental data and theories that look "unreasonable" (in contradiction with the dominant paradigm) may need a long time (and affirmation by different laboratories) before they are deemed publishable. Notorious is the affair around the publication of Benveniste's "unreasonable" experimental data on the [[memory of water]] in [[Nature]]. | |||

==The scientific literature== | ===The scientific literature=== | ||

<blockquote> ''…If the study is found to be good enough, the findings are published and acknowledged by the wider scientific community…'' </blockquote> | <blockquote> ''…If the study is found to be good enough, the findings are published and acknowledged by the wider scientific community…'' </blockquote> | ||

The way in which scientific research is presented in published form is governed by sometimes quite rigid conventions. Although they differ slightly from one field to another, a scientific paper generally has an 'Introduction', which gives a brief background to the question that is being addressed, a 'Methods' section, which details the experimental procedures in enough detail to allow them to be replicated independently, a 'Results' section which objectively details the findings, and a 'Discussion' section in which the authors interpret the findings and relate them to other work. | |||

[[Peter Medawar]] (1915-1987), Nobel laureate in Physiology and Medicine, in his article “Is the scientific paper a fraud?” <ref>Medawar, P. B. [http://maagar.openu.ac.il/opus/static/binaries/editor/bank66/medawar_paper_fraud_1.pdf “Is the scientific paper a fraud?”], BBC Third Programme, Listener 70, 12 September 1963. </ref> argued that the scientific paper in its orthodox form embodies "a totally mistaken conception, even a travesty, of the nature of scientific thought." Because the results of an experiment are interpreted only at the end (in the discussion section) of scientific papers, this gives the impression that those conclusions are drawn by induction or deduction from the reported evidence. However, explains Medawar, it is the ''expectations'' that a scientist begins with that provide the incentive for the experiments, determine their nature, and determine which observations are relevant and which are not. Only in the light of these initial expectations do the activities described in a paper have any meaning at all. The expectation, the original hypothesis, according to Medawar, is not the product of inductive reasoning but of inspiration — educated guesswork. | |||

==Confirmation== | ===Confirmation=== | ||

<blockquote> ''…But, it isn’t enough to prove a hypothesis once. Other researchers must also be able to repeat the study and produce the same results, if the hypothesis is to remain valid…'' </blockquote> | <blockquote> ''…But, it isn’t enough to prove a hypothesis once. Other researchers must also be able to repeat the study and produce the same results, if the hypothesis is to remain valid…'' </blockquote> | ||

Sometimes | Sometimes scientists make errors in the design, execution or analysis of their experiments, so it is common for other scientists to try to repeat experiments, especially when the results were surprising. <ref>Georg Wilhelm Richmann was killed by lightning in 1753 when attempting to replicate the kite experiment of Benjamin Franklin. Krider P (2006) Benjamin Franklin and lightning rods ''Physics Today'' 59:42, [http://ptonline.aip.org/journals/doc/PHTOAD-ft/vol_59/iss_1/42_1.shtml available online]</ref> Accordingly, scientists keep detailed records of their experiments, to provide evidence of their effectiveness and integrity and assist in reproduction. Generally, in publishing their work, it is considered essential that scientists describe their methods in enough detail to allow them to be repeated by others. However, a scientist cannot record ''everything'' about an experiment; he (or she) reports what he believes to be relevant. This can cause problems if some supposedly irrelevant feature is questioned. For example, Sidney Ringer's experiments with isolated frog hearts first led him to declare that the heart could continue to beat if kept in a simple saline solution. However, he later discovered that the solution had been made up not with distilled water but with London tap water, which contained a significant amount of calcium carbonate. He retracted his first reports, and is now known as the scientist who showed that calcium is important for the contractions of the heart. <ref>Carafoli E (2002) Calcium signalling: a tale for all seasons ''PNAS USA'' [http://www.pnas.org/cgi/content/abstract/99/3/1115 99:115-22]</ref> | ||

==Statistics== | ===Statistics=== | ||

<blockquote>''…If the initial study was carried out using a small number of samples or people, larger studies are also needed. This is to make sure the hypothesis remains valid for bigger group and isn't due to chance variation…'' </blockquote> | <blockquote>''…If the initial study was carried out using a small number of samples or people, larger studies are also needed. This is to make sure the hypothesis remains valid for bigger group and isn't due to chance variation…'' </blockquote> | ||

Scientists analyse their data using the theory and methods of [[Statistics]], which arose from [[probability theory]]. Statistical analysis essentially involves methods for drawing conclusions from data that involve multiple sources of error. | |||

This | Statistical analysis is a part of hypothesis testing in many areas of science. This formalises the criteria for disproof by allowing statements of the form: | ||

"If our hypothesis is true, the chance of getting the results that we observed is (say) only 1 in 20 or less (P < 0.05); therefore the hypothesis is probably wrong, and so we reject it.'' | |||

For instance, we might predict that a given chemical will produce a certain effect. However what we often test is not this, but the ''[[null hypothesis]]'' - that the chemical will have '''no''' effect. The reason is that, if our original hypothesis is vague about how big an effect to expect, then we cannot disprove it, as we can't exclude the possibility that the effect is too small to measure. However, we ''can'' disprove the null hypothesis (by showing an effect). Ideally, we choose hypotheses that give precise predictions, but this is often unrealistic. In medicine for example, we might expect a new drug to be effective in a particular condition from our understanding of its mechanism of action. Even so, we might not know how big an effect to expect because of many uncertainties - how many people will be resistant to the drug? for example, and how quickly will tolerance to the drug develop in people who respond well? | |||

This is not hypothesis testing in Popper's sense, because the hypothesis is not put at any hazard of disproof. Verification of this type is something that Popper considered to be, at best, weak corroborative evidence, partly because it is impossible to measure the support that such evidence provides. <ref>In appendix ix to ''The Logic'', Popper states: "As to degree of corroboration, it is nothing but a measure of the degree to which hypothesis ''h'' has been tested...it must not be interpreted therefore as a degree of the rationality of our belief in the truth of ''h''...rather it is a measure of the rationality of accepting, tentatively, a problematic guess."</ref> | |||

In the 18th century, an English clergyman, [[Thomas Bayes]] (1702-1761) proved a result, now known as [[Bayes' theorem]], that, in some interpretations, provides a formal method for revising beliefs in the light of new evidence <ref>Bellhouse DR (2004) [http://www.york.ac.uk/depts/maths/histstat/bayesbiog.pdf The reverend Thomas Bayes FRS: a biography to celebrate the tercentenary of his birth] Statistical Science 19:3-43</ref>. It has been argued that [[Bayesian statistics]] can be used to provide a basis for support by induction, and some areas of science use these approaches. Bayesian statistics measures how the probability that a hypothesis is true changes as a result of observations, but it depends on assigning initial values to the probabilities of alternative outcomes of an experiment. This is not always possible because of the difficulty of assigning these ''a priori'' probabilities in any meaningful way. | |||

===Progress and controversy in science=== | |||

<blockquote> ''...Over time, scientific opinion can change. This is because new technologies can allow us to re-examine old questions in greater detail.'' </blockquote> | |||

Although skepticism, or doubt, has long been recognised as an important element in all science, Kuhn argued that scientific opinion does not change easily in fundamental things. In particular, one theory or world view is replaced by another not because many scientists are 'converted' to the new world view. Instead, a new theory begins as an unfashionable alternative that is often derided, but gains adherents as its advantages become apparent to new scientists entering the field, while the adherents of the old view fight a 'rear-guard action' to defend it. [[Barbara McClintock]]'s work on regulatory elements that control gene expression won her the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1983, but in 1953 she decided to stop trying to publish detailed accounts of her work, because of the puzzlement and hostility of her peers. In 1973 she wrote: | |||

:"Over the years I have found that it is difficult if not impossible to bring to consciousness of another person the nature of his tacit assumptions when, by some special experiences, I have been made aware of them. ...One must await the right time for conceptual change"<ref>McClintock B (1987) The discovery and characterization of transposable elements: the collected papers of Barbara McClintock, ed John A. Moore. Garland Publishing, Inc. ISBN 0-8240-1391-3. (Introduction)</ref> | |||

Kuhn focused attention on the unexplainable phenomena as the key to scientific revolutions, which he called "paradigm shifts". One example reported in ''The Structure of Scientific Revolutions'' dates back to the mathematical astronomer Claudius [[Ptolemy]], who lived in Egypt in the 2nd century CE. The improvements in astronomical observation, and the accumulation of more data during that time required more and more elaborate explanations to reconcile the observational data with the accepted belief that the earth was the centre of the solar system, and indeed of the universe. By the time of [[Copernicus]] (1473-1543), so much evidence had accumulated suggesting that the sun was in fact the center of the solar system, the whole infrastructure of theories broke down, leading the way to acceptance of a new heliocentric world picture. Yet, it took more than a century before all astronomers were convinced. When [[Einstein]] showed in 1905 that there is no [[ether (physics)|ether]], or at least that the concept is superfluous and may be removed from physics by Ockham's razor, many of the older generation of physicists did not accept this paradigm shift and died believing in ether; they were not converted, the ether concept died out. | |||

New observations about natural phenomena continue to lead to such revolutions in biology, plate tectonics, particle physics, and many other branches of science. | |||

==Alternative views== | |||

<blockquote>''"The progress of science is often affected more by the frailties of humans and their institutions than by the limitations of scientific measuring devices. The scientific method is only as effective as the humans using it. It does not automatically lead to progress."'' Steven S. Zumdahl</blockquote> | |||

The success of science, as measured by the technological achievements that have changed our world, have led many to conclude that this success is because of the methodological rules that scientists follow. However, not all philosophers accept this conclusion; for example, [[Paul Feyerabend]] (1924-1994) denied that science is genuinely a methodological process. In his book ''Against Method'' he argued that scientific progress is ''not'' the result of applying any particular rules.<ref> Feyerabend PK (1975) [http://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/ge/feyerabe.htm ''Against Method, Outline of an Anarchistic Theory of Knowledge''] Reprinted, Verso, London, UK, 1978; for a critical review, see [http://www.springerlink.com/content/p704x52113gg17j7/fulltext.pdf "Against too much method"] by John Worrall</ref> Instead, he concluded almost that 'anything goes', in that for any particular 'rule' there are abundant examples of successful science that have proceeded in a way that seems to contradict it.<ref>[http://www.galilean-library.org/feyerabend.html Feyerabend's 'anything goes' argument explained] at the Galilean Library. Criticisms such as his led to the [[strong programme]], a radical approach to the sociology of science. | |||

</ref> To Feyeraband, there is no real difference between science and other areas of human activity characterised by reasoned thought. A similar sentiment was expressed by [[T.H. Huxley]] in 1863: "The method of scientific investigation is nothing but the expression of the necessary mode or working of the human mind. It is simply the mode at which all phenomena are reasoned about, rendered precise and exact."<ref>Huxley TH (1863) [http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/1863huxley.html From a 1863 lecture series aimed at making science understandable to non-specialists]</ref> | |||

Some scientists focus their activity on making precise and detailed observations of a phenomenon, gathering data, organizing it in sensible ways, making it accessible to other scientists. We do not disqualify those scientists as ‘scientists’ on the grounds they do not employ a scientific method. Other scientists might use their observational data to generate testable hypotheses, and other scientists might test those hypotheses by experiment, and others try to reproduce the findings. That illustrates an instance of the scientific method in action realized by the combined effort of two or more scientists working with different methods, not necessarily in one generation. Regardless of the hopefully rational approach that each scientist employs in her 'scientific method', none can leave their biases and passions outside their mind. Sometimes biases and passions contribute the advancement of science. The scientific method is the endeavor of humans, prone to error for many reasons, prone to creative insights by nature. But scientists agree on the need for verifiable knowledge, and they cannot suppress the emergence of new perspectives and paradigms. | |||

In his 1958 book, ''Personal Knowledge,'' the chemist and philosopher [[Michael Polanyi]] (1891-1976) criticized the view that the scientific method is purely objective and generates objective knowledge. Polanyi thought that this was a misunderstanding of the scientific method, and argued that scientists do and must follow their passions in appraising facts and in choosing which questions to investigate. He concluded that a structure of liberty is essential for the advancement of science — that the freedom to pursue science for its own sake is a prerequisite for the production of knowledge.<ref> [http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/relativism/ Relativism] entry at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy</ref> | |||

[[ | |||

[ | |||

==The changing nature of science== | |||

Charles Darwin was an amateur scientist, a man of independent means and broad ranging interests who worked to satisfy his own curiosity. Still in the early 20th century, science was the province of individuals with wide interests. Albert Einstein was working as clerk in a patent office in Bern in 1905, the year that he published four papers in ''Annalen der Physik'' that are now each recognised as hugely important; the four papers discuss the particulate nature of light; Brownian motion; the theory of special relativity; and the equivalence of matter and energy. | |||

In the 20th century, science became largely professionalised, conducted increasingly by specialised experts employed in Universities or research institutes, and increasingly governed by the priorities of funding bodies, which in turn have become increasingly influenced by the political priorities of the Governments that are the source of the funding for research. | |||

The 'lone scientist' is now a rare animal; most science is now a collaborative enterprise, often conducted in large teams where each member of the team supplies a specific area of specialised expertise. Most of Frederick Sanger's scientific papers, published between 1945 and 1980, were either authored by him alone or with just one other co-author. This is now unusual in the Life Sciences, where most papers have several authors and many have ten or more. In experimental high-energy physics, papers with more than 100 authors from 40 or more institutions are the rule.<ref>For example, see a randomly picked article in the May 2009 issue of the European Physical Journal C [http://dx.doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-009-0995-1 DOI]</ref> | |||

< | |||

Increasingly, scientists work towards specified ambitious goals; a prime example is the [[Human Genome Project]], a research program involving hundreds of laboratories across many countries directed at sequencing the entire human genome. This 13-year project, coordinated by the U.S. Department of Energy and the National Institutes of Health, was completed in 2003. | |||

Thus the 20th century saw a transition from ''curiosity-driven research'' to ''hypothesis-driven research'' and then to ''goal-directed research''. These changes were accompanied by major changes in the sociology of the scientific community. Research scientists today mostly have a very narrowly specialised technical expertise, are professionally employed, funded directly or indirectly by Governments, research charities or industry, and generally work within a team that may be part of a multinational network of teams working to a common goal. | |||

== | ==Notes and references== | ||

{{reflist|2}} | |||

Latest revision as of 12:27, 24 March 2022

Statue of David Hume. "Man is a reasonable being; and as such, receives from science his proper food and nourishment: But so narrow are the bounds of human understanding, that little satisfaction can be hoped for in this particular..." Hume recognised clearly the difficulties in gaining a general understanding merely by accumulating observations.

Scientists use a scientific method to investigate phenomena and acquire knowledge. They base the method on verifiable observation — i.e., on replicable empirical evidence rather than on pure logic or supposition — and on the principles of reasoning.[1] [2] Scientists propose explanations — called hypotheses — for their observed phenomena, and perform experiments to determine whether the results accord with (support) the hypotheses or falsify them. They also formulate theories that encompass whole domains of inquiry, and which bind supported hypotheses together into logically coherent wholes. They refer to theories sometimes as ‘models’, which often have a mathematical or computational basis.[3] [4]

Components of the scientific method

Science is said to proceed on two legs, one of theory (or, loosely, of deduction) and the other of observation and experiment (or induction). Its progress, however, is less often a commanding stride than a kind of halting stagger — more like the path of the wandering minstrel than the straight-ruled trajectory of a military marching band. The development of science is influenced by intellectual fashions, is frequently dependent upon the growth of technology, and in any case, seldom can be planned far in advance, since its destination is usually unknown.

|

A simplified depiction of the cyclic nature of scientific research: An initial observation triggers an idea that is being developed into a hypothesis which — if funds, equipment and the necessary expertise are available — may lead to experimental data (or other forms of verifiable evidence) that can support or contradict the hypothesis or other existing theoretical descriptions of the system at hand, which in turn can trigger independent replication or falsification of this particular experiment if the relevant information are made available to other researchers. Traditionally, this publication step would be achieved solely via articles in toll-access scientific journals but initiatives like Open Access, Open Source and Open Data are increasingly making all these individual steps public, which is facilitated through the use of Web 2.0 technologies in what has come to be called Science 2.0.

Generally accepted components of a scientific method are:

- Observation.[6] Observations do not just await discovery, rather they often result from active exploration, questioning, sharing ideas and information among scientists, thinking creatively. Moreover, according to most current views, observations do not come into view wholly independently of some predetermined or preconceived theory; scientists struggle to keep their preconceptions and presuppositions out of the picture.[7][8] Sometimes "believing is seeing".

- Hypothesis. Hypotheses are general statements, formulated as plausible conjectures to explain existing observations and predict future observations.

- Experiment.[9] An experiment is a procedure carried out under controlled conditions to discover an unknown effect; to provide confirming or disconforming evidence for a hypothesis, often based on whether a prediction of the hypothesis ensues; or, to illustrate an accepted theory. Not all areas of science involve direct experimentation; as an example for data-driven research, the Human Genome Project largely involved (highly technical) interpretation of gene sequences, but the data were obtained by experimental investigation.

- Theory. A theory incorporates a set of supported hypotheses into a logical framework that overall explains the phenomenon studied. Not all of the statements of a theory are necessarily open to experimental testing, but many are expected to be for a theory to be considered scientific. The scientific method usually involves further testing of its accepted satisfactory overall explanation of a phenomenon, as natural phenomena usually have more observable features than the theorist knows at the time the theory hatches. A good theory will make accurate predictions about the behavioral aspects of the phenomenon studied, suggesting experiments to test its overall explanatory power.

- Prediction. A prediction is a logical deduction from a hypothesis (or theory) by which the hypothesis (or theory) can be tested experimentally.

- Testing. A 'test' of a hypothesis is an experiment, the results of which might falsify (disprove) the hypothesis; if the test does not falsify the hypothesis, the test is said to support ('confirm') the hypothesis. The same holds for testing theories.

- Causal explanation. Satisfactory explanations are often regarded as those that establish a cause-effect relationship. However, many scientists argue that concepts of causality are not obligatory to science, but are well-defined only under particular conditions.[10] [11]

- Skeptical open mindedness. Progress in extending existing theoretical frameworks is made possible by a scientific culture that encourages challenges to existing theory, while also demanding that far-reaching conjectures are validated by exceptional evidence.[12]

Philosophy of scientific methods

If the purpose of scientific methodology is to prescribe or expound a system of enquiry or even a code of practice for scientific behavior, then scientists seem to be able to get on very well without it. Most scientists receive no tuition in scientific method, but those who have been instructed perform no better as scientists than those who have not. Of what other branch of learning can it be said that it gives its proficients no advantage; that it need not be taught or, if taught, need not be learned? Peter Medawar[13]

| Evolutionary processes and, in general, scientific explanations of the world are often in contrast with the immediate and simple explanations that our brain gives of reality (e.g. the sun seems to turn around the earth, the earth seems to be flat), and are influenced by what Francis Bacon called "idola"[[14]] (false notions or tendencies which distort the truth [[15]]).[16] |

Non-scientists often represent science as a dry, mechanical activity, involving accumulating large numbers of facts, whether by simple observations or by technologically ingenious means. Indeed, this is an important part of science, and technological advances in our ability to interrogate the world have played an essential part in the advance of science: we need only consider how the light microscope, then the electron microscope, and now the scanning tunneling microscope[17] and two-photon laser scanning confocal microscopy have radically changed our understanding of the world. However, observations, things that we might sometimes call 'facts', are just the beginning. Thus, according to Charles Darwin (1809-1882), "science consists in grouping facts so that general laws or conclusions may be drawn from them."[18]

But what exactly do we mean by ‘facts’? We sometimes disagree about the ‘facts’ we see around us, and some things in the world are at odds with our understanding. How much can we trust our senses to allow us to believe what we see? How do scientists ‘group’ facts? How do they choose which facts to attend to, and is it possible to do this in an objective way? And having done this, how do they draw any broader conclusions? Most importantly, how can we ever know more than we observe directly? We live in a world that is not directly understandable: we all interpret everything that we see and hear and feel, and to make sense of what our senses tell us we need to construct explanations, or formulate theories. Our explanations identify some things as important and other things as irrelevant; they lead us to pay attention to some things and not others, and they lead us to expect some things to happen and not others — they lead, in other words, to predictions.

Nothing about this is unique to science, but scientists attempt to harness these universal elements of reasoning in a consistent, systematic and rigorous manner, and in a way that minimizes bias. What we call the 'scientific method' is an account of how scientists gather and report observations in ways that will be understood by other scientists and accepted as valid evidence, and how they construct explanations that are consistent with the world, and that can withstand logical and experimental scrutiny and provide the foundations for further increases in understanding.

For many, the scientific approach begins with an attitude of skepticism — a willingness to question accepted beliefs, expressed by René Descartes in 1637 as a determination "never to accept anything for true which I did not clearly know to be such". The English philosopher Francis Bacon (1561-1626), often described as the pioneer of the modern scientific method, proposed that scientists should "empty their minds" of self-evident truths and, by observation and experimentation, should draw general conclusions by a process known as induction.[19] Bacon described many of the commonly accepted principles of scientific method, but recognised that to interpret nature, something more than observation and reason is needed:

- ...the universe to the eye of the human understanding is framed like a labyrinth, presenting as it does on every side so many ambiguities of way, such deceitful resemblances of objects and signs, natures so irregular in their lines and so knotted and entangled. ... No excellence of wit, no repetition of chance experiments, can overcome such difficulties as these. Our steps must be guided by a clue...[20]