Note (music): Difference between revisions

imported>John R. Brews (Start page) |

imported>John R. Brews (notation) |

||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

By "quality" is meant that unmistakable character which distinguishes a note on one instrument from the note of same pitch as given by another...difference of quality, so far as it is not due to adventitious circumstances, can only be ascribed to differences of vibration-form, and so to differences in the relative amplitude and phases of the simple-harmonic constituents. | By "quality" is meant that unmistakable character which distinguishes a note on one instrument from the note of same pitch as given by another...difference of quality, so far as it is not due to adventitious circumstances, can only be ascribed to differences of vibration-form, and so to differences in the relative amplitude and phases of the simple-harmonic constituents. | ||

|} | |} | ||

What Lamb refers to as "quality" of a tone also is referred to as [[timbre]]. | |||

==Notation== | |||

{{Image|Musical clefs.png|right|100px|Musical clefs arranged on a stave.}} | |||

The pitch of a sound is indicated in musical notation by placing a symbol for the note on a ''stave'', an array of parallel lines, as shown in the figure. The names of the notes are indicated. The symbol for the note indicates its duration. Examples are shown in the figure, with the longest or ''whole note'' at the bottom and successively shorter notes stacked above.<ref name=Taylor/> | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Revision as of 12:03, 14 June 2012

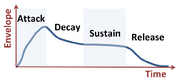

The amplitude of a musical note varies in time according to its sound envelope.[1]

In music, a note is an abstract representation of the pitch and duration of a tone. The pitch designated by a note is objective only in the case of a simple tone (also called a pure tone) such as produced by a tuning fork, which consists of only a single frequency of vibration, in which case the pitch is uniquely related to that frequency at a given loudness.[2] A musical instrument on the other hand, produces a tone, which is a superposition of various frequencies with various amplitudes and phases peculiar to the instrument, and also affected by the manner of play that determines the sound envelope of the note (referred to by Lamb below as "adventitious circumstances"). To quote Lamb:[3]

|

One musical note may differ from another in respect of pitch, quality, and loudness. The pitch is usually estimated as that of the first simple-harmonic vibration in the series, viz. that of lowest frequency, but if the amplitude of this first component be relatively small, and especially if it fall near the lower limit of the audible scale, the estimated pitch may be that of the second component. By "quality" is meant that unmistakable character which distinguishes a note on one instrument from the note of same pitch as given by another...difference of quality, so far as it is not due to adventitious circumstances, can only be ascribed to differences of vibration-form, and so to differences in the relative amplitude and phases of the simple-harmonic constituents. |

What Lamb refers to as "quality" of a tone also is referred to as timbre.

Notation

The pitch of a sound is indicated in musical notation by placing a symbol for the note on a stave, an array of parallel lines, as shown in the figure. The names of the notes are indicated. The symbol for the note indicates its duration. Examples are shown in the figure, with the longest or whole note at the bottom and successively shorter notes stacked above.[4]

References

- ↑ Stanley R. Alten (2010). “Sound envelope”, Audio in Media, 12th ed. Cengage Learning, p. 13. ISBN 049557239X.

- ↑ The pitch of pure tones varies somewhat with sound level, perhaps by as much as 5% and varying with the individual listener. Susan Hallam, Ian Cross, Michael Thaut (2011). The Oxford Handbook of Music Psychology. Oxford University Press, p. 50. ISBN 0199604975.

- ↑ Horace Lamb (2004). The Dynamical Theory Of Sound, Reprint of 1925 Edwin Arnold Ltd. 2nd ed. Courier Dover, p. 4. ISBN 048643916X.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedTaylor