Models of the stability of states: Difference between revisions

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz (New page: {{subpages}} {{main|Foreign internal defense}} {{seealso|Insurgency}} {{seealso|Foreign internal defense operations}} {{TOC-right}} {{subpages}} FID planning makes use of several conceptua...) |

imported>Caesar Schinas m (Robot: Changing template: TOC-right) |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

{{seealso|Insurgency}} | {{seealso|Insurgency}} | ||

{{seealso|Foreign internal defense operations}} | {{seealso|Foreign internal defense operations}} | ||

{{TOC | {{TOC|right}} | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

FID planning makes use of several conceptual ''' models of the strength and stability of nation-states''', especially in the context of [[insurgency]] where they are detailed. Not all states need assistance to suppress insurgency, while in other cases, no external assistance is available. The latter was often the case when the insurgency was directed, by the native population, at a colonial power. | FID planning makes use of several conceptual ''' models of the strength and stability of nation-states''', especially in the context of [[insurgency]] where they are detailed. Not all states need assistance to suppress insurgency, while in other cases, no external assistance is available. The latter was often the case when the insurgency was directed, by the native population, at a colonial power. | ||

Revision as of 05:35, 31 May 2009

- See also: Insurgency

- See also: Foreign internal defense operations

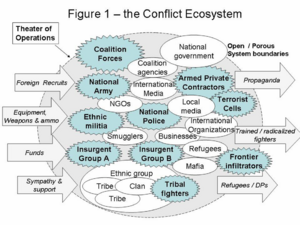

FID planning makes use of several conceptual models of the strength and stability of nation-states, especially in the context of insurgency where they are detailed. Not all states need assistance to suppress insurgency, while in other cases, no external assistance is available. The latter was often the case when the insurgency was directed, by the native population, at a colonial power.

A key part of a foreign internal defense (FID) mission is that its goal is to enable the nation and its institutions to move into the realm of those states that both provide for their citizens and interact constructively with the rest of the world. Two broad categories of country need at least some aspects of FID assistance. The obvious category is of weak and failed states, but there are also needs in generally strong states that face specific problems such as terrorism, piracy and illegal drugs.

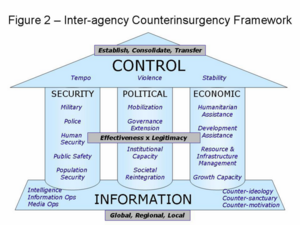

This section includes a number of models that help recognize when either the preconditions for insurgency exist, or how insurgents are operating against the HN. Through the various models, the need for security of the population is mentioned most often; without security, it is difficult to impossible to deal with other problems causing instability, such as public health or economics.

The FID paradigm is inherently cooperative, with at least one nation helping strengthen the state. FID is a different approach than defense against external invasion or settling a major civil war. FID is never a quick process. The major power(s) uses nonmilitary and military means to increase the capability of the host nation (HN) to resist insurgency. FID includes the economic stabilization of host countries.

Myths and Fallacies

The term Global War on Terror has been criticized, but there may be utility in examining a war not specifically on the tactic of terror, but in one or more, potentially cooperating insurgencies. "the utility of analyzing the war on terrorism using an insurgency/counterinsurgency conceptual framework. Additionally, the recommendations can be applied to the strategic campaign, even if it is politically unfeasible to address the war as an insurgency."[1] Cordesman points out some of the myths in trying to have a worldwide view of terror:[2]

- Cooperation can be based on trust and common values: One man’s terrorist is another man’s terrorist.

- A definition of terrorism exists that can be accepted by all.

- Intelligence can be freely shared.

- Other states can be counted on to keep information secure, and use it to mutual advantage.

- International institutions are secure and trustworthy.

- Internal instability and security issues do not require compartmentation and secrecy at national level.

- The “war on terrorism” creates common priorities and needs for action.

- Global and regional cooperation is the natural basis for international action.

- Legal systems are compatible enough for cooperation.

- Human rights and rule of law differences do not limit cooperation.

- Most needs are identical.

- Cooperation can be separated from financial needs and resources

Social scientists, soldiers, and sources of change have been modeling insurgency for nearly a century, if one starts with Mao.ref name=MaoProtracted>Mao Tse-tung (1967), On Protracted War, Foreign Languages Press</ref> Counterinsurgency models, not mutually exclusive from one another, come from Kilcullen, McCormick, Barnett and Eizenstat; see insurgency for the material that deals with factors that predispose toward insurgency.

Kilcullen's Pillars

David Kilcullen developed a model identifies the participants in an actual or potential insurgency.

It shows a box defined by geographic, ethnic, economic, social, cultural, and religious characteristics. Inside

the box are governments, counterinsurgent forces, insurgent leaders, insurgent forces, and the general population, which is made up of three groups:

- those committed to the insurgents

- those committed to the counterinsurgents

- those who simply wish to get on with their lives. The FID team must identify all these components that are present in the HN, and identify their interactions. encouraging those supportive of the counterinsurgents and the general population, and discouraging the needs of the isnurgents.. Kilcullen has one model His model is less focused on a hierarchy of command and control, and more on establishing shared values. "Obviously enough, you cannot command what you do not control. Therefore, unity of command (between agencies or among government and non-government actors) means little in this environment." Unity of command is one of the axioms of military doctrine[4]

The three pillar model repeats later as part of the gaps to be closed to end an insurgency.

As in swarming, Kilcullen "depends less on a shared command and control hierarchy, and more on a shared diagnosis of the problem [i.e., the distributed knowledge of swarms], platforms for collaboration, information sharing and deconfliction. Each player must understand the others’ strengths, weaknesses, capabilities and objectives, and inter-agency teams must be structured for versatility (the ability to perform a wide variety of tasks) and agility (the ability to transition rapidly and smoothly between tasks)."

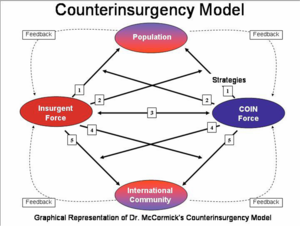

McCormick Magic Diamond

McCormick’s model[5] is designed as a tool for counterinsurgency (COIN), but develops a symmetrical view of the required actions for both the Insurgent and COIN forces to achieve success. In this way the counterinsurgency model can demonstrate how both the insurgent and COIN forces succeed or fail. The model’s strategies and principle apply to both forces, therefore the degree the forces follow the model should have a direct correlation to the success or failure of either the Insurgent or COIN force.

The model depicts four key elements or players:

- Insurgent Force

- Counterinsurgency force (i.e., the government)

- Population

- International community.

All of these interact, and the different elements have to assess their best options in a set of actions:

- Gaining Support of the Population

- Disrupt Opponent’s Control Over the Population

- Direct Action Against Opponent

- Disrupt Opponent’s Relations with the International Community

- Establish Relationships with the International Community

Barnett and connecting to the core

In Thomas Barnett's paradigm,[6] the world is divided into a "connected core" of nations enjoying a high level of communications among their organizations and individuals, and those nations that are disconnected internally and externally. In a reasonably peaceful situation, he describes a "system administrator" force, often multinational, which does what some call "nation-building", but, most importantly, connects the nation to the core and empowers the natives to communicate -- that communication can be likened to swarm coordination. If the state is occupied, or in civil war, another paradigm comes into play, which is generally beyond the scope of FID: the leviathan, a first-world military force that takes down the opposition regular forces. Leviathan is not constituted to fight local insurgencies, but major forces. Leviathan may use extensive swarming at the tactical level, but its dispatch is a strategic decision that may be made unilaterally, or by an established group of the core such as NATO or ASEAN.

FID can grow out of the functioning of the "system administrator", be that a single dominant country (e.g., France in Chad), or with a multinational group such as ECOMOG, the military arm of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), in Sierra Leone. In the Sierra Leonian situation, the primary Leviathan was Great Britain, with Operation Barras, which involved special reconnaissance, direct action, and hostage rescue.

Eizenstat and closing gaps

Broad views of FID involve closing "gaps",[7] some of which can be done by military advisors and even combat assistance, but, even more broadly, helping the Host Nation (HN) be seen as responsive. To be viable, a state must be able to close three "gaps", of which the first is most important:

- security: protection "against internal and external threats, and preserving sovereignty over territory. If a government cannot ensure security, rebellious armed groups or criminal nonstate actors may use violence to exploit this security gap—as in Haiti, Nepal, and Somalia."

- capacity: The most basic are the survival needs of water, electrical power, food and public health, closely followed by education, communications and a working economic system.[8] "An inability to do so creates a capacity gap, which can lead to a loss of public confidence and then perhaps political upheaval. In most environments, a capacity gap coexists with—or even grows out of—a security gap. In Afghanistan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, for example, segments of the population are cut off from their governments because of endemic insecurity. And in postconflict Iraq, critical capacity gaps exist despite the country’s relative wealth and strategic importance."

- legitimacy: closing the legitimacy gap is more than an incantation of "democracy" and "elections", but a government that is perceived to exist by the consent of the governed, has minimal corruption, and has a working law enforcement and judicial system that enforce human rights.

Note the similarity between Eizenstat's gaps and Kilcullen's three pillars.[9]

Cordesman and Security

Other than brief "Leviathan" takedowns, security building appears to need to be regional, with logistical and other technical support from more developed countries and alliances (e.g., ASEAN, NATO). Noncombat military assistance in closing the security gap begins with training, sometimes in specialized areas such as intelligence. More direct, but still noncombat support, includes intelligence, planning, logistics and communications. It is well to understand that counterterrorism, as used by Cordesman, does not mean using terrorism against the terrorism, but an entire spectrum of activities, nonviolent and violent, to disrupt an opposing terrorist organization. The French general, Joseph Gallieni, observed, while a colonial administrator in 1898,

A country is not conquered and pacified when a military operation has decimated its inhabitants and made all heads bow in terror; the ferments of revolt will germinate in the mass and the rancours accumulated by the brutal action of force will make them grow again[10]

Both Kilcullen and Eizenstat define a more abstract goal than does Cordesman. Kilcullen's security pillar is roughly equivalent to Eizenstat's security gap:

- Military security (securing the population from attack or intimidation by guerrillas, bandits, terrorists or other armed groups)

- Police security (community policing, police intelligence or “Special Branch” activities, and paramilitary police field forces).

- Human security, building a framework of human rights, civil institutions and individual protections, public safety (fire, ambulance, sanitation, civil defense) and population security.

"This pillar most engages military commanders’ attention, but of course military means are applied across the model, not just in the security domain, while civilian activity is critically important in the security pillar also ... all three pillars must develop in parallel and stay in balance, while being firmly based in an effective information campaign."[9]

Anthony Cordesman, while speaking of the specific situation in Iraq, makes some points that can be generalized to other nations in turmoil.[11] Cordesman recognizes some value in the groupings in Samuel Huntington's idea of the clash of civilizations,[12] but, rather assuming the civilizations must clash, these civilizations simply can be recognized as actors in a multinational world. In the case of Iraq, Cordesman observes that the burden is on the Islamic civilization, not unilaterally the West, if for no other reason that the civilization to which the problematic nation belongs will have cultural and linguistic context that Western civilization cannot hope to equal.

References

- ↑ Canonico, Peter J. (December 2004). An Alternate Military Strategy for the War on Terrorism. U.S. Naval Postgraduate School.

- ↑ Cordesman, Anthony H. (29 October 2007), Security Cooperation in the Middle East, Center for Strategic and International Studies

- ↑ Kilcullen, David (2004), Countering Global Insurgency: A Strategy for the War on Terrorism

- ↑ Department of the Army (14 June 2001). Field Manual 3-0: Operations (PDF).

- ↑ McCormick, Gordon. "The Shining Path and Peruvian terrorism". RAND Corporation.

- ↑ Barnett, Thomas P.M. (2005). The Pentagon's New Map: The Pentagon's New Map: War and Peace in the Twenty-first Century. Berkley Trade.

- ↑ Eizenstat, Stuart E. (January/February 2005), "Rebuilding Weak States", Foreign Affairs (no. 1)

- ↑ Sagraves, Robert D (April 2005), The Indirect Approach: the role of Aviation Foreign Internal Defense in Combating Terrorism in Weak and Failing States, Air Command and Staff College

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Kilcullen, David (28 September 2006), Three Pillars of Counterinsurgency

- ↑ McClintock, Michael (November 2005). Great Power Counterinsurgency. Human Rights First.

- ↑ Cordesman, Anthony H. (August 1, 2006). The Importance of Building Local Capabilities: Lessons from the Counterinsurgency in Iraq. Center for Strategic and International Studies.

- ↑ Huntington, Samuel P. (1996). The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. Simon & Schuster.