Bill O'Reilly (cricket)

At the time of his death, Bill O'Reilly (1905–1992) was widely recognised as cricket's greatest ever spin bowler. That assessment has subsequently been challenged by the careers of Muttiah Muralitharan and Shane Warne but, even so, O'Reilly's legacy as one of the sport's greatest players remains intact.[1][2] Widely known as "Tiger" for his aggressively competitive style of play, he had been a schoolteacher before his Test career began and he later became a renowned broadcaster and journalist.

Cricket career

William Joseph O'Reilly was born on 20 December 1905 at White Cliffs in New South Wales. He began his first-class career in the 1927–28 Australian season, playing for New South Wales. He was a right arm specialist leg break and googly bowler and a left-handed tail-end batsman. He was 33 when the Second World War began but he returned for the 1945–46 season and then retired. In the whole of his first-class career, he played in 135 matches and took ten wickets in a match (10wM) 17 times, an exceptional ratio. His best innings performance was a return of 9/38 against Somerset on the 1934 tour of Great Britain.

Test debut

O'Reilly made his Test debut for Australia at the Adelaide Oval on 29 January 1932, when he was selected for the fourth Test of that season's series against the visiting South Africans. He bowled in partnership with the veteran Clarrie Grimmett and provided him with solid support. Grimmett was Australia's matchwinner, taking fourteen wickets. O'Reilly took 2/74 and 2/81 as Australia won by 10 wickets. He also scored a useful 23 in his only innings. In the fifth and final Test at the Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG), which Australia won by an innings and 72 runs, O'Reilly did not bowl in the first innings as Australia used only their pace and seam bowlers. In the second innings, he took an impressive 3/19 in just nine overs. The match was one of the lowest-scoring Tests on record – South Africa were all out twice for 36 and 45; Australia (without Don Bradman who had been injured while fielding) scored 153.

Bodyline series

O'Reilly had done enough to merit selection for all five Tests of the infamous "Bodyline" series in the 1932–33 season. He took 27 wickets in the five matches, an outstanding achievement without, as Wisden commented, "anyone noticing much, given what else was happening".[2] That was an unfair assessment because the England team certainly noticed him in the second Test at the MCG. England, using Douglas Jardine's controversial leg theory tactic, had won the first Test at the Sydney Cricket Ground (SCG) by 10 wickets.

The Melbourne match was a different matter because the pitch was not as lively as expected and, by the fourth day, was taking "the spin of the ball to a pronounced degree".[3] Jardine blundered by failing to recognise the condition of the pitch and selected four pace bowlers with only batsman Walter Hammond able to spin the ball at need. Bradman, however, assessed the conditions accurately and Australia picked three spinners – O'Reilly, Grimmett and Bert Ironmonger – with Tim Wall their sole fast bowler. The match cemented O'Reilly's growing reputation as a world-class player.

Bradman won the toss and chose to bat first. Australia had reached 67/2 when he himself came in to bat. He had missed the first Test because of illness and the Australians hoped his return would bring about an Australian recovery. He was promptly bowled by Bill Bowes without scoring and it then looked as if England were on course for another victory. Australia reached 194/7 at close of play and were all out for 228 next morning. Jack Fingleton had scored a fighting 83 as their batsmen again struggled against the pace of Bowes, Harold Larwood and Bill Voce. Australia used a pace/spin combination with Wall and O'Reilly sharing most of the bowling. England were 161/9 at the close and were all out for 169 on the third morning. O'Reilly took 5/63, the first time he achieved five wickets in an innings (5wI) in a Test match. Wall took 4/52. With an unexpected lead of 59, Australia set about increasing it and this time Bradman scored "a brilliant 103 not out".[3] This was a master-class performance because Australia were all out for only 191. Wisden says Bradman "sacrificed many runs to keep the bowling" while he was partnered by the tail-enders. He reached his century just before the last wicket fell. It left England needing 251 to win on a pitch that was rapidly deteriorating. They reached 43/0 by the close but, on the fourth day, O'Reilly (5/66) and Ironmonger (4/26) combined to bowl them out for 139, Australia winning by 111 runs. O'Reilly's match return was 10/129, the first time he had taken ten wickets in a match (10wM) in a Test. Despite Bradman's century, Wisden says "O'Reilly had most to do with the success of Australia" and also that, "bowling into the wind, he made the ball float", a curious expression which means the ball did not reach the batsman as soon as he would normally expect it to and so it was difficult for him to time his shot correctly.[3]

It is fair to say that O'Reilly wasn't noticed much in the last three Tests, although he was easily the best Australian bowler. The third Test at the Adelaide Oval was the flashpoint of the whole Bodyline fiasco. Wisden described the match as "probably the most unpleasant ever played" (at the time). O'Reilly took six wickets in the match which England won by 338 runs as Jardine brought the sport into disrepute and almost caused an international incident. England won the fourth Test at The Gabba by 6 wickets and this meant they had won the series outright to regain the Ashes. Australia scored 340 in their first innings and O'Reilly as the mainstay of Australia's bowling took 4/120 to restrict England to 356 – this was an outstanding performance on a pitch that favoured batting. Australia were all out for 175 in the second innings and England scored 162/4 to win. Although it was academic in series terms, the fifth Test at the MCG was keenly contested by both teams. England won by 8 wickets. O'Reilly again bowled well by taking 3/100 in their first innings to restrict their lead to 19 (all three wickets were of specialist batsmen). As also happened at The Gabba, however, Australia collapsed in their second innings and England won easily.

1934 tour of Great Britain

O'Reilly was chosen for his first overseas tour when the 1934 Australians visited Great Britain and recovered the Ashes. O'Reilly was an outstanding member of the team and was chosen as one of the Wisden Cricketers of the Year in the Almanack's 1935 edition.[1]

Legacy

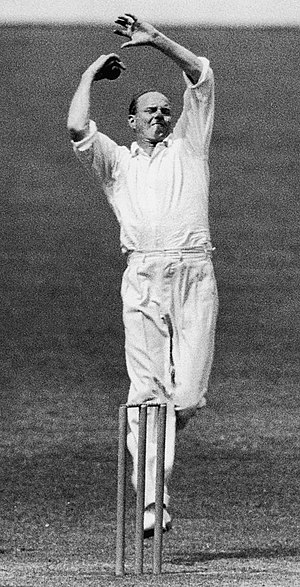

One of O'Reilly's greatest admirers was R. C. Robertson-Glasgow. Always an imaginative writer, he recognised O'Reilly's bowling action as something quite out of the ordinary:[2]

As with those more florid opponents of legendary heroes, there seemed to be more arms than Nature or the rules allow. During the run-up, a sort of fierce galumph, the right forearm worked like a piston; at delivery the head was ducked low as if to butt the batsman on to his stumps. But it didn't take long to see the greatness; the control of leg-break, top-spinner and googly; the change of pace and trajectory without apparent change in action; the scrupulous length; the vitality; and, informing and rounding all, the brain to diagnose what patient required what treatment.

Broadcasting and journalism

O'Reilly had been a schoolteacher before his cricket career took off and, after he retired from playing, he became a highly respected commentator and journalist on the sport.

Bradman and O'Reilly

Although Bradman and O'Reilly expressed the utmost admiration for each other as players, there is evidence of underlying personal dislike between the two which may have been fuelled by sectarian conflict. O'Reilly was a Catholic of Irish ancestry and Bradman was a Protestant. While there was sectarianism in Australian society, there is no definite proof that Australian cricketers practised it. It has been said that O'Reilly never concealed his personal dislike of Bradman but he never let it surface in his writings or broadcasts. Equally, it did not stop them playing together very effectively at grade, state and national level. Bradman was more obviously at odds with O'Reilly's friend Fingleton, another Catholic, and the supposed animosity may have been assumed by association.[4]

The conflict may be hearsay because, on the record, there is mutual admiration. O'Reilly's view of Bradman was that "compared with him, great batsmen like Greg Chappell and Allan Border were mere 'child's play'".[4] When O'Reilly died, Bradman paid tribute to him and said he was "the greatest bowler I have ever faced or watched".[2]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Bill O'Reilly – Cricketer of the Year. Wisden Cricketer's Almanack. John Wisden & Co. Ltd (1935).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Bill O'Reilly – Obituary. Wisden Cricketer's Almanack. John Wisden & Co. Ltd (1993).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Australia v England 1932–33 (Second Test). Wisden Cricketer's Almanack. John Wisden & Co. Ltd (1934).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Derriman, Philip. Letters reveal the real Don, The Age, 30 October 2004.