Evolution of appetite regulating systems

For the course duration, the article is closed to outside editing. Of course you can always leave comments on the discussion page. The anticipated date of course completion is 01 February 2011. One month after that date at the latest, this notice shall be removed. Besides, many other Citizendium articles welcome your collaboration! |

Introduction

Recently, there has been extensive research into the neuroendocrine mechanisms controlling appetite. The pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) gene has been identified as playing an important role in these mechanisms, particularly through production of the peptide alpha-MSH. POMC and its end-products have not only been identified in humans, but also in a large range of other vertebrates. This has lead to further research into the origins of the POMC gene and the evolution of appetite regulating systems. This article details the structure and function of the POMC gene. It highlights variations between species, allowing a potential evolutionary route, originating at a common ancestral gene, to be mapped out.

Human POMC

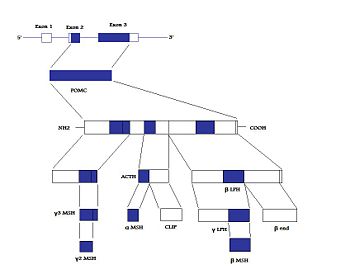

The human pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) gene encodes a hormone precursor protein, which itself is then cleaved, with the help of prohormone convertase enzymes, into a number of different peptides. These include the melanocyte-stimulating hormones (alpha-, beta-, gamma- MSH), adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), the lipotropins, and beta-endorphin [1]. ACTH and the MSHs are referred to as the melanocortins and all have the same core amino acid sequence, HFRW [2].

The POMC gene is found on chromosome 2p23[3], and is made up of three exons and two “large” introns[4]. Only exons two and three are translated however. Exon two codes for the signal peptide and the initial N-terminal amino acids, while exon three codes for “most of the translated mRNA” [3].

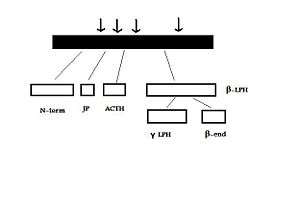

After excision of the introns to form a “parent” POMC, this molecule is then cleaved into its various peptides, as mentioned above, by PCs, specifically PC1 and PC2[4]. These enzymes act at cleavage sites consisting of paired basic residues, arginine and lysine, and end-products of their action depend on which sites are used. As PC1 and PC2 act on different sites, and their expression varies in different tissues, processing of POMC’s peptides is tissue-specific [3]. For example, the anterior pituitary corticotroph cells only express PC1, which results in the cleavage of POMC into the NH2-terminal peptide (N-term), joining peptide (JP), ACTH, β-LPH, and some γ-LPH and β-endorphin (β-end) - See "POMC cleavage by PC1" diagram. The latter two peptides are produced because the “last cleavage site is only partially used”[3]. However, in melanotroph cells, found in the intermediate lobe of the rodent pituitary, and the human hypothalamus, and placenta, both PC1 and PC2 are expressed. This means that all the cleavage sites are used and smaller peptides are produced [4]). N-term is therefore cleaved to the γ-MSHs, ACTH gives rise to α-MSH and CLIP (corticotrophinlike intermediate lobe peptide) and γ-LPH to β-MSH[3].

POMC is expressed in the hypothalamus in the central nervous system, specifically the arcuate nucleus, as well as the nucleus tractus solitarius of the caudal medulla. It is also found in the anterior and intermediate pituitary, the immune system, and the skin.

Wot all the end products of pomc do

Where they act

Physiology and relation to appetite regulation

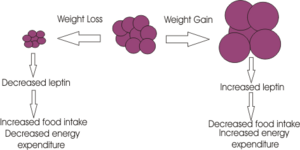

Evidence for POMC related to food regulating systems Relationship between POMC and other hormones eg leptin *diagram*

A-msh

Mc receptors

Pomc neurons and arc nucleus

Leptin, grhelin, npy et

diagram

Species Variation in POMC Gene

evolutionary tree diagram Chordata (vertebrates)

~ Agnatha – Lamprey

~ Gnathostomes

~ Chondrichthyes (cartilaginous fish)

~ Osteichthyes (bony fish)

~ Subclass Actinopterygii (ray-finned fish;) - paddlefish

~ Subclass Sarcopterygii (lobe-finned fish)

~ Tetrapods (mammals, birds, reptiles?)

Invertebrates

Summary/Conclusion

Remember you are writing an encyclopedia article; it is meant to be readable by a wide audience, and so you will need to explain some things clearly, without using unneccessary jargon. But you don't need to explain everything - you can link specialist terms to other articles about them - for example adipocyte or leptin simply by enclosing the word in double square brackets.

About References

To insert references and/or footnotes in an article, put the material you want in the reference or footnote between <ref> and </ref>, like this:

<ref>Person A ''et al.''(2010) The perfect reference for subpart 1 ''J Neuroendocrinol'' 36:36-52</ref> <ref>Author A, Author B (2009) Another perfect reference ''J Neuroendocrinol'' 25:262-9</ref>.

Look at the reference list below to see how this will look.[5] [6]

If there are more than two authors just put the first author followed by et al. (Person A at al. (2010) etc.)

Select your references carefully - make sure they are cited accurately, and pay attention to the precise formatting style of the references. Your references should be available on PubMed and so will have a PubMed number. (for example PMID: 17011504) Writing this without the colon, (i.e. just writing PMID 17011504) will automatically insert a link to the abstract on PubMed (see the reference to Johnsone et al. in the list.)

[7]

Use references sparingly; there's no need to reference every single point, and often a good review will cover several points. However sometimes you will need to use the same reference more than once.

How to write the same reference twice:

Reference: Berridge KC (2007) The debate over dopamine’s role in reward: the case for incentive salience. Psychopharmacology 191:391–431 PMID 17072591

First time: <ref name=Berridge07>Berridge KC (2007) The debate over dopamine’s role in reward: the case for incentive salience. ''Psychopharmacology'' 191:391–431 PMID 17072591 </ref>

Second time:<ref name=Berridge07/>

This will appear like this the first time [8] and like this the second time [8]

Figures and Diagrams

You can also insert diagrams or photographs (to Upload files Cz:Upload)). These must be your own original work - and you will therefore be the copyright holder; of course they may be based on or adapted from diagrams produced by others - in which case this must be declared clearly, and the source of the orinal idea must be cited. When you insert a figure or diagram into your article you will be asked to fill out a form in which you declare that you are the copyright holder and that you are willing to allow your work to be freely used by others - choose the "Release to the Public Domain" option when you come to that page of the form.

When you upload your file, give it a short descriptive name, like "Adipocyte.png". Then, if you type {{Image|Adipocyte.png|right|300px|}} in your article, the image will appear on the right hand side.

References

- ↑ Yang YK et al. (2003) Recent developments in our understanding of melanocortin system in the regulation of food intake. Obesity Reviews 4(4):239-48

- ↑ Dores RM et al. (2005) Trends in the evolution of the proopiomelanocortin gene. General and Comparative Endocrinology 142(1-2):81-93.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Raffin-Sanson et al. (2003) Proopiomelanocortin, a polypeptide precursor with multiple functions: from physiology to pathological conditions. European Journal or Endocrinology 149:79–90.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 Millington GW. (2007) The role of proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurones in feeding behaviour. Nutrition and Metabolism 4:18.

- ↑ Person A et al. (2010) The perfect reference for subpart 1 J Neuroendocrinol 36:36-52

- ↑ Author A, Author B (2009) Another perfect reference J Neuroendocrinol 25:262-9

- ↑ Johnstone LE et al. (2006)Neuronal activation in the hypothalamus and brainstem during feeding in rats Cell Metab 2006 4:313-21. PMID 17011504

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 Berridge KC (2007) The debate over dopamine’s role in reward: the case for incentive salience. Psychopharmacology 191:391–431 PMID 17072591