Gulf of Tonkin incident

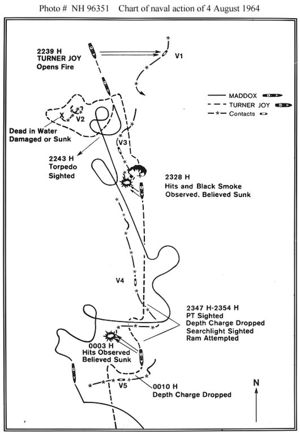

Track chart of the action involving USS Maddox (DD-731) and USS Turner Joy (DD-951) on the night of 4 August 1964, during the second part of the Gulf of Tonkin incident. Many of the observations reflected in this chart were later determined to be inaccurate.

The Gulf of Tonkin incident, in August 1964, was the event that led President Lyndon B. Johnson to order air attacks on the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) and vastly intensify U.S. forces in the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam). Two attacks by DRV fast attack craft were described to the Congress, one on the lone destroyer USS Maddox, and the second, on the night of August 4, on the Maddox and the USS Turner Joy (DD-951), which had been sent to reinforce Maddox. The destroyer patrol also had on-call air support.

In response to a presumed attack, the President requested and received the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution authorizing military response. The basic assumption of the incident were that North Vietnamese naval vessels of a fast attack craft type, had attacked U.S. destroyers, in international waters of the Gulf of Tonkin, on the nights of August 2 and August 4th. On August 5th, President Johnson ordered retaliatory airstrikes on North Vietnamese bases associated with the vessels in question. A number of facts, and some matters of interpretation, were not available to the Congress or the public at the time, and, indeed, even to the President and military. Robert McNamara, who urged action at the time, later quoted William Bundy:

Miscalculation by both the U.S. and North Vietnam is, at the end, at the root of the best hindsight hypothesis of Hanoi's behavior. In simple terms, it was a mistake for an Administration sincerely resolved to keep its risks low to have had the 34A operations and the destroyer patrol take place even in the same time period. Rational minds could not readily have foreseen that Hanoi might confuse them...but rational calculations should have taken account of the irrational.[1]

Questions still remain, and some of the questions themselves are questionable. For example, it has been asked if the U.S. planned to escalate. There is a blurry line, however, between contingency planning to escalate and an intention to escalate. It has been asked if the U.S. provoked a North Vietnamese response, and part of the blurriness comes from there being concurrent or near-concurrent U.S. activities that certainly could have seemed threatening to the North Vietnamese, but may not have represented an actual U.S. intent to trigger a response. In turn, there are North Vietnamese actions that certainly could have seemed threatening to the people on the spot. There was literal night and fog of war, in which both sides may not have been certain exactly what the other's units were doing, and why.

While it was claimed that North Vietnamese patrol boats had attacked U.S. warships in the Gulf, there is considerable data, especially recently declassified signals intelligence from the National Security Agency that indicates that there was no second attack.

Conditions conducive to an incident

USS Maddox (DD-731) in early 1964. Note that the ship had recently been refitted with an SPS-40 air search radar.

Captain John J. Herrick, USN, Commander DesDiv 192 (left) and Commander Herbert L. Ogier, USN, Commanding Officer of USS Maddox (DD-731), on board Maddox on 13 August 1964. They were in charge of the ship during her engagement with three North Vietnamese motor torpedo boats on 2 August 1964.

Lieutenant Commander Dempster M. Jackson, USN, Executive officer of USS Maddox (DD-731), kneels next to the hole made by the machine gun bullet that hit his ship's Mk.56 director pedestal during the engagement between Maddox and three North Vietnamese motor torpedo boats on 2 August 1964. The bullet is lodged in the hole.

USS Ticonderoga (CVA-14) refuels from USS Ashtabula (AO-51) while operating off the coast of Vietnam.

Prior to the incidents with the destroyers, under the then-classified U.S. Pacific Command(CINCPAC) Operations Plan (OPPLAN 34A), there had been a series of covert U.S.-RVN attacks on DRV coastal boats and shore installations, carried out by MACV-SOG. The Maddox was conducting a DESOTO PATROL, an operation with two purposes. Its public purpose was to demonstrate that the U.S. did not agree with the 12-mile limit of territorial waters claimed by the DRV. In addition, it had a signals intelligence mission, with intercept equipment and technicians in a van strapped to a destroyer's deck. The SIGINT mission of the Maddox was to record the North Vietnamese signals being generated after the alert from the 34A operation. It must be understood clearly that the DESOTO and 34A operations were separate, but were happening in approximately the same time and place.

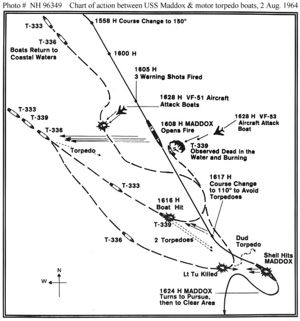

While there still are inconsistencies, it is likely that fire was exchanged on August 2, between North Vietnamese fast attack craft and the Sumner-class destroyer USS Maddox on August 2, although it is unclear which side shot first. There is a good deal more question about the August 4 incident, involving of Maddox and Forrest Sherman-class destroyer USS C. Turner Joy. [2]

There are also some matters that remain uncertain, including North Vietnamese thinking.

- There had been MACV-SOG naval raids against North Vietnam as recently as July 30, which were within its territorial limits and included attacks on land. While these raids were not conducted by overt warships, did the North Vietnamese believe the close-in warship, on August 2, was to be part of another attack?

- Close-in destroyer patrols, originally targeted against Communist China, were not freedom of navigation exercises alone; destroyers assigned to Operation DESOTO had national-level signals intelligence equipment and technicians, in a temporarily mounted on-deck van, operating under direction of the National Security Agency

- North Vietnam was added to the DESOTO targeting in December 1962, so their appearance was not new to the North Vietnamese, and considerably preceded the creation of MACV-SOG

- The North Vietnamese were said to have fired first, but the captain of the Maddox, in a report released at the time, said he fired warning shots

- The attacks were described as including torpedoes. fast attack craft reported in the incident are generally identified as Swatow-class, which are not equipped with torpedoes.

- North Vietnamese P-4 class torpedo boats had been ordered into the area, according to U.S. communications intelligence [3]

- The P-4 class torpedo boats, visually sighted by the Maddox, would have needed an additional 30 minutes to get into torpedo range; the Maddox fired warning shots first, and the boats may them have been damaged by American aircraft. On August 3, additional communications intercepts showed that the DRV itself was searching for two of its torpedo boats.[4]

The U.S. had prepared plans for escalation against North Vietnam. "The U.S. reprisal represented the carrying out of recommendations made to the President by his principal advisers earlier that summer and subsequently placed on the shelf."[5]

Retaliatory airstrikes

Operating on his authority as Commander-in-Chief, Johnson had retaliatory strikes launched against the DRV. Whether it was his lack of military experience and his unwillingness to listen to military advisors, or that his concern for domestic politics overrode tactical considerations, he went on national television to announce the airstrikes, while some of them were still inbound to their targets — which could have been alerted by his broadcast. According to H.R. McMaster, Johnson would not delay his television broadcast because he wanted it to be sure to make the late evening news, and the deadlines for morning newspapers. [6]

McNamara and Johnson appeared to believe that deliberate attacks had taken place. Senior military and intelligece officials, however, increasingly doubted the circumstances. They included LTG Bruce Palmer (Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations, U.S. Army), Ray Cline (deputy director for intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency), and the Director of the State Department Bureau of Intelligence and Research , and the Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern affairs, as well as more junior staff. Some of the junior staff were to become much more prominent, such as Alexander Haig and Daniel Ellsberg. Cline said, however, "...we knew it was bum dope we were getting from the United States Seventh Fleet, but we were told to give only the facts with no elaboration on the nature of the evidence. Everyone knew how volatile LBJ was. He did not like to deal with uncertainties."[7]

Gulf of Tonkin Resolution

Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara discussed, with the President. how the two alleged attacks were to be explained to the Congress.

Secretary McNamara: Right. And we're going to, and I think I should also, or we should also at that time, Mr. President, explain this Op Plan 34-A, these covert operations. There's no question but what that had bearing on. And on Friday night, as you probably know, we had four TP [McNamara means PT] boats from Vietnam manned by Vietnamese or other nationals, attack two is lands. And we expended, oh, a thousand rounds of ammunition of one kind or another against them. We probably shot up a radar station and a few other miscellaneous buildings. And following twenty-four hours after that, with this destroyer in that same area, undoubtedly led them to connect the two events.[8]

On August 5, President addressed Congress, asking for urgent authority to act. [9] He invoked the U.S.-initiated supplemental protocol to the SEATO Treaty. [10] South Vietnam was not a SEATO member, but was covered by a bilateral agreement with the United States.[11]

Congress passed a joint resolution stating that international peace and security in Southeast Asia were "vital to" the national interest. The resolution authorized President Johnson "to take all necessary steps, including the use of armed force," to assist any SEATO "member of protocol state" requesting US help in defending its freedom. [12]

Actions in the aftermath of the Resolution

Department of State cables Saigon and Vietnam embassies and CINCPAC requesting comment on key points in a Shortly afterward, the State department cabled the U.S. Embassy in Saigon and the U.S. Pacific Command, requesting a "tentative high level paper on next courses of action in SEA."... "the next ten days to two weeks should be short holding phase in which we would avoid action that would in any way take onus off Communist side for escalation."

The cable said the DESOTO patrol will not be resumed and new 34A (covert maritime) operations would not be undertaken. After sketching "essential elements of the political and military situations in both SVN and Laos, as well as respective strategies re negotiations, the cable then listed proposed "limited pressures" to be exerted on the DRV in Laos and in NVN during the period, "late August tentatively through December." [5]

On September 10, President Johnson authorized the DESOTO and 34A operations to resume, but suspended them again, on September 18, due to a reported threat against U.S. destroyers by North Vietnamese patrol boats. He authorized the 34A operations to resume on October 3, to include two "probes", an attempted junk (Vietnamese type of boat) capture and ship-to-shore bombardment of radar sites.[5]

References

- ↑ William Bundy, Vietnam Manuscript, quoted in Robert S. McNamara, In Retrospect, pp. 140-141

- ↑ , Letter from Carl Macy, Senate Foreign Relations committee, to Lewis Tordella, Deputy Director of the National Security Agency, Tonkin Gulf Intelligence "Skewed" According to Official History and Intercepts, vol. George Washington University National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book 132, January 24, 1972

- ↑ Hanyok, Robert (January 24, 1972), Skunks, bogies, silent hounds and the flying fish: the Gulf of Tonkin mystery, 2-4 August 1964, "Tonkin Gulf Intelligence "Skewed" According to Official History and Intercepts", National Security Agency Cryptologic Quarterly (declassified excerpt) George Washington University National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book 132, pp. 13-18

- ↑ Hanyok, p. 20

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 , Chapter 2, "Military Pressures Against North Vietnam, February 1964-January 1965," Section 1, pp. 106-157

- ↑ McMaster, H. R. (1998), Dereliction of Duty: Johnson, McNamara, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Lies That Led to Vietnam, Harper Perennial

- ↑ Hanyok, p. 39

- ↑ John Prados, ed., LBJ Tapes on the Gulf of Tonkin Incident, National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 132

- ↑ President Johnson's Message to Congress; Joint Resolution of Congress H.J. RES 1145, August 5, 1964

- ↑ Protocol to the Manila Pact, September 8, 1954

- ↑ Dwight D. Eisenhower, Eisenhower's Letter of Support to Ngo Dinh Diem, October 23, 1954, vol. Department of State Bulletin. November 15, 1954, pp.735-736

- ↑ President Johnson's Message to Congress; Joint Resolution of Congress H.J. RES 1145, August 5, 1964