Vietnam War ground technology

Vietnam War Ground Technology is not limited to U.S. systems alone., since there are comparisons to examine (e.g., M-16 (rifle) vs. AK-47, and earlier weapons such as the SKS), and VC/NVA field air defense. It deals with Army aviation, both fixed- and rotary-wing aircraft, organic to ground units. Forward air controllers deals with the coordination of high-performance U.S. Air Force and U.S. Navy high-performance aircraft in close air support. Special reconnaissance includes the direction, by long-range, clandestine ground penetration teams, of air attack against the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

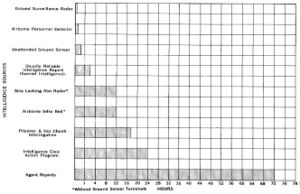

Ground intelligence

Personnel detectors

- See also: Materials MASINT

A Vietnam-era sensor, the XM2, generally known as the "people sniffer", detected ammonia concentrations in air, which indicated the presence of groups of people or animals. While it was sensitive, but not selective for people, many water buffalo became targets. Nevertheless, it was considered the best sensor used by the 9th Infantry Division, because, as opposed to other MASINT and SIGINT sensors, it could give helicopter-borne troops real-time detection of targets [1]

IGLOO WHITE remote sensors

Vietnam-era acoustic MASINT sensors included the "Acoubuoy" (36 inches long, 26 pounds)... floated down by camouflaged parachute and caught in the trees, where it hung to listen. The Spikebuoy (66 inches long, 40 pounds) planted itself in the ground like a lawn dart. Only the antenna, which looked like the stalks of weeds, was left showing above ground." [2]

These sensors, however, transmitted via relay aircraft to a computer center in Thailand. Their data was used principally for directing airstrikes, rather than alerting ground troops to nearby enemy.

The jungle was an enemy

Vietnamese jungle caused much military difficulty; various technical means were used against it, but it generally proved more effective to maneuver around it than through it. Approaches included tearing through it and killing it. Never completely solved was the Viet Cong's extensive use of underground tunnel complexes in remote areas.

Rome Plow

A key device was called the Rome Plow, based on the standard military D7E tracked earthmover, equipped a special tree-cutting blade manufactured by the Rome Company of Rome, Georgia. The plow blade cut six inches above the surface, shearing off most of the vegetation but leaving the root structure to prevent erosion. A corner of the blade was extended by a rigid "stinger" with which the operator attacks the larger trees by a succession of stabbings and dozer turnings.[3]

Operation RANCH HAND

RANCH HAND missions began in November 1961, using six C-123 Provider transports, modified for aerial-spraying operations, left Pope AFB, North Carolina. While they were not officially part of Air Commando units, for security reasons, they were treated as part of the 4400th. Once at Tan Son Nhut Air Base, they were designated Tactical Air Force Transport Squadron, Provisional One. The first three arrived 7 January 1962. [4]

Their mission was to spray agricultural defoliants against jungle, denying cover to the Viet Cong. Initially, they used a commercial weedkiller called "Agent Purple", for the color-code on the 55-gallon drums. While Purple was effectively nontoxic, there was North Vietnamese attempt to call it chemical warfare. For the potential propaganda value, Washington officials objected to the political risk, but there was much demand from Army commanders who liked the results.

A different defoliant went into use with the expansion of the program in March 1965. Again, it was a commercial preparation, called Agent Orange after the color coding of its containers. While Agent Orange itself was considered nontoxic to humans, and was primarily composed of conventional herbicides 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T, many batches had an exceptionally toxic byproduct of the manufacturing process, which caused significant contamination, and long-term health consequences, including defects, on both Vietnamese and Americans. This was also used by Canadian Forces in Canada, who documented the later-understood health effects. [5]

Remote surveillance and Trail operations

This section focuses on bttlefield air interdiction against the Ho Chi Minh trail, without consideration if the location of the specific surveillance and strikes were or were not secret at the time. Here, the emphasis is on the tactics and techniques. Perhaps the best-known BAI technique was the ARC LIGHT strike by B-52 bombers dropping massive tonnages of bombs, although less well-known techniques, such as AC-130 gunships used against the trail were effective. Some of the operations against the Trail were in Laos and Cambodia, and these missions were generally not revealed, usually for complex international as well as U.S. domestic political reasons. Clearly, the enemy survivors knew they were being bombed; 63 or 126 ton bombings from B-52s are difficult to ignore.

Special reconnaissance personnel installed unmanned MASINT sensors, such as seismic, magnetic, and other personnel and vehicle detectors, for subsequent remote activation, so their data transmission allows the emplacement to remain clandestine. Remote sensing, in the broadest sense, began with US operations against the Laotian part of the Ho Chi Minh trail, in 1961.

The first purpose-built AC-130 gunships began their combat evaluation in late 1967. Flying armed reconnaissance missions against the Trail in Laos and South Vietnam, they were highly effective, especially against trucks that they located with BLACK CROW sensors that detected the electrical noise produced by the spark plugs. Maj Gen William G. Moore, Air Force deputy chief of staff, research and development, said the first models “far exceeded fighter-type kill ratios on enemy trucks and other equipment.”[6]

The very limited results from LEAPING LENA led to two changes. First, US-led SR teams, under Project DELTA, sent in US-led teams. Second, these Army teams worked closely with US Air Force Forward Air Controllers (FAC), which were enormously helpful in directing US air attacks by high-speed fighter-bombers, BARREL ROLL in northern Laos and Operation STEEL TIGER. While the FACs immediately helped, air-ground cooperation improved significantly with the use of remote geophysical MASINT sensors, although MASINT had not yet been coined as a term.

Helicopters and Air Mobility

- See also: Air Assault

Helicopter mobility is very much associated with the Vietnam War. In air assault, the history of heliborne operations is discussed, and then the Howze Board, attached helicopter operations with the 173rd Airborne Brigade, and the deployment of the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile). Apropos of the 1st Cav, separate articles already exist on the Battle of the Ia Drang and the Battle of Bong Son.

When the Kennedy Administration took office, Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara made exploration of new ways of mobility a high priority. In 1962, he expressed dissatisfaction with Army conservative, and created a well-funded research organization to evaluate extensive air mobility. While it had a formal name, it was generally called the Howze Board after its chief, Hamilton H. Howze.

With McNamara's support, the Board revised its recommendations to create a helicopter-borne combat unit of division size. Large-scale field tests proved it could be effective in battle, and the 1st Cavalry Division (1st Cav) was redesignated the 1st Cavalry Division (airmobile) and sent to Vietnam in July 1965. There had been moderately successful tests in Vietnam by the 173rd Airborne Brigade, arriving in May and first fighting in June, but it became clear that the approach used by the 173rd, attaching helicopters for each mission, was not nearly as effective as a unit that had infantry and helicopters training together as a team. This teaming was a basic aspect of the 1st Cav, which first went into combat in the Battle of the Ia Drang in October 1965.

In mid-1965, the 11th Air Assault Division (Test), the experimental force in AIR ASSAULT II, was reflagged as the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) and sent to Vietnam. Their first assignment was to crush Giap's buildup around the Ia Drang river; there are indications that Giap intended to meet the 1st Cav and learn techniques to fight the airmobile forces.

The 1st Cav learned lessons in the Battle of the Ia Drang in October and November 1965, and refined its techniques at the Battle of Bong Son in December 1965 through February 1966.[7]

Well handled airmobile forces could dominate at the tactical and operational levels, but neither they nor the United States Air Force could hold ground. While U.S. forces could deliver massive casualties, Giap was quite prepared to fight an attritional strategy, aimed at U.S. opinion. COL (ret.) Harry Summers, a U.S. Army historian and strategist, is said to have said to a North Vietnamese counterpart during talks, "We never lost a battle." The DRV colonel said "true, but irrelevant."

Military aircraft are inherently dangerous, especially at low altitude where helicopters often operated. Most jet aircraft have the gliding performance of a brick when they lose power. A helicopter that loses power, but maintains the integrity of its rotors, is at a few thousand feet of altitude, and has a competent pilot, can "autorotate" to a landing, the airflow of the fall spinning the rotors and generating lift. At low altitude, there is no time to generate that lift. Jet fighters do have ejection seats to blast pilots clear of an impending crash, where helicopter crews have neither ejection seats nor parachutes.

In the 1st Cav, there were scouts in very light observation helicopters (OH-6 "Loach"), light (UH-1 "Huey") that could carry 10-12 soldiers into battle or deliver machine gun and rocket fire in direct support, and medium (CH-47 Chinook) and large (CH-54 "The Hook") helicopters that could lift artillery into firebases supporting the heliborne infantry.

Using scouts and infantry to locate the enemy, and call in artillery and air strikes, was one airmobile tactic. Another was to harass and attrit the enemy with a series of stinging ambushes and raids, using a doctrine now considered swarming. In these and other cases, however, the division name was appropriately chosen -- these were more classically cavalry rather than infantry missions.

Landing zones

Depending on the tactical situation, a LZ might be prepared by artillery, air strikes, or escorting armed helicopters. Since the suppressive fire did not always drive off defenders, there was a balance of stealth vs. fire; small insertions sometimes had the helicopters make several decoy landings, silently landing a team at one quick stop. the first infantry companies landed in "slicks." These were unarmed Bell UH-1D "Hueys" that could carry 12 men and their gear.

Weapons support

One of the features of the airmobile division design was minimizing the role of medium artillery, which could be moved only by large helicopters, and heavy artillery, which could not be airlifted at all. The division had a large number of helicopters designated as "aerial rocket artillery", which could saturate areas with 2.75" rockets.

Fire bases were set up with medium Boeing CH-47 Chinook helicopters, which could transport the 2-ton 105mm light howitzers, light vehicles, and ammunition; the larger CH-54 Tarhe ("the hook") lifted the larger 8-ton 155mm medium howitzers that gave the firebase greater range. Generally, the greater mobility of the 105, and the quick availability of armed helicopters and jet fighter-bombers, made 155s and heavier howitzers less important, unless they were already in a semipermanent base. See tube artillery below for artillery employment doctirne.

Command and control

Command and control could be very good or very bad. Company-sized forces would often land with their commanding captains, and, as with Moore at X-Ray, sometimes with more senior officers. When the levels of command did not micromanage, a battalion commander (lieutenant colonel) or higher commander could keep an overview of the engagement, and bring in reinforcements, as well as air and artillery strikes, as appropriate.

There were times, however, where the captain might stay airborne, the lieutenant colonel a bit higher, the colonel commanding the brigade at the next altitude, and possibly the major general division commander and lieutenant general corps commander in their own command and control helicopters. When this turned into micromanagement, it was said, ruefully, "never, in the course of human events, have so many, been so supervised, by so few."

Meanwhile the whole operation was covered by helicopter gunships--"Hueys" equipped with rockets, grenade launchers and door-mounted machine guns. Although its maximum speed was only 127 mph, the Huey could dart and dive and swerve with enough agility to evade most ground fire. Close air support from fixed-wing fighter-bombers was readily available.

Defense against helicopters

Although some heavier anti-aircraft artillery was encountered on the Ho Chi Minh trail, the most serious threat to U.S. helicopters tended to be Soviet-designed 12.7mm (equal to U.S. .50 caliber) or 14.5 mm heavy machine guns, on man-portable antiaircraft mountings. While vehicle-mounted U.S. M2HB .50 machine guns were on pedestal mounts that allowed a high elevation suitable for antiaircraft fire, the U.S. infantry-carried tripod was not suitable for antiaircraft fire. While the U.S. ground forces did not need an antiaircraft mount, it is striking how effective a relatively simple mount, with appropriate sights, could be against helicopters.

Individual equipment

Equipment for the individual soldier changed. For some time, there had been an international debate over conventional rather than "assault" rifles. The conventional rifle, such as the M-1 Garand, fired a high-power bullet, had a relatively small magazine, and was best for carefully aimed fire. Assault rifles were an evolution of the less than successful submachine guns of WWII, which fired a low-power pistol bullet, continuously or in bursts. Assault rifles, such as the U.S. M-16 or Soviet AK-47 fired an intermediate power bullet from a large magazine, sometimes in continuous bursts. Many Communist soldiers used the SKS, inferior to the M-16 and AK-47 for use in the conditions of Vietnam.

A consideration for the U.S. was that the M-14 rifle, which had replaced the M-1, was too heavy for many of the smaller Vietnamese allies. The M-16's smaller (5.56mm vs. 7.62mm) bullet allowed a soldier to carry more ammunition, and the trend had been away from carefully aimed fire to suppressive fire that froze the enemy until air and artillery could hit him. The 5.56mm bullet did not always penetrate jungle.

The new M-16 rifle was a shorter, lighter and more versatile assault weapon than the old M-1 or its replacement the M-14. It fired a light bullet at high muzzle velocity, which gave great killing power at ranges under 400 yards. Its rapid fire made it ideal in ambushes, although variations from the designed ammunition, as well as training problems and some mechanical problems, made early versions less reliable than the Communist AK-47. Both the AK-47 and M-16 had advantages and disadvantages; neither was the ideal infantry rifle. The AK-47 was heavier, especially when using the 30 round magazine — which allowed longer fire without reloading than did an M-16. While the M-16 had a 20 round magazine, it was often loaded with no more than 18 rounds, which seemed to reduce jamming.

Another U.S. individual weapon was a 40mm grenade, which could be fired farther than a hand grenade could be thrown. The grenades could be launched from a M-79 single-shot weapon, rather like a large shotgun and able to fire a shotgun-like round. Alternatively, the M-203 launcher attached to the underside of a M-16 rifle, below the barrel. Limited use was made of a hand-cranked automatic grenade launcher, the Mark 19, primarily on river patrol boats or vehicle-borne troops as it was too heavy for foot soldiers. Other versions were used on helicopters.

While the Communist side did not have an exact equivalent to the 40mm grenade launcher, they used the RPG-7 rocket-assisted grenade launcher, originally intended as an antitank weapon, and did not have the fragmentation, smoke, and other variants available for the M79/M203. Its warhead was 85mm, which projected from the muzzle of the 40mm launcher. RPG rounds had more blast than the U.S. grenade, but were directional and slower to load. [8] The closest U.S. equivalent was the M-72 Light Anti-tank Weapon (LAW), with a smaller, but comparable in anti-armor performance. The M-72 was not reloadable but had a throwaway launcher, so it was a bit more convenient to use than the RPG-7.

The M-60 medium machine gun was powerful and reliable, but suffered from the logistical problem of using different ammunition (7.62mm) than the M-16. In modern U.S. infantry, it has been replaced by the M-249 squad automatic weapon firing 5.56mm.

Heavy weapons

Tube artillery

Beyond what was available from armed helicopters and from fighter-bombers, fire from 105mm howitzers, relatively easy for medium helicopters to lift, was invaluable, and was a regular part of Army doctrine. 155mm howitzers could be lifted by the heaviest helicopters, but were more likely to be moved, by ground, to a firebase. The long-range 8" howitzer and 175mm gun were only road-mobile, but had sufficient range that their presence did not alert the enemy to impending operations in a specific area.

Forward observers helped control artillery fire, and computers supported artillery. The Field Artillery Digital Automatic Computer (FADAC), went into development in 1958, and remained usable into the 1980s.[9]

Marine doctrine, however, generally was less artillery-dependent, featuring the close air support aspect of the Marine Air-Ground Task Force. In the summer of 1968, however, Marine units "leapfrogged" from fire support bases, defined as artillery positions located where they needed a minimum amount of infantry in defense. The bases tended to hold both artillery and an infantry battalion command post, the companies of which fanned out from the firebases. They were built approximately 8000 meters apart, providing overshoot of approximately 3000 meters to counter enemy mortar fire.[10]

Gunships

Especially for night defense of fixed positions such as Special Forces/CIDG camps, fixed-wing gunships, originally "Puff, the Magic Dragon," an Air Force AC-47 transport fitted with three electrically operated 7.62mm machine guns miniguns 100 bullets per second, and had a major night role in dropping flares. The fixed-wing gunship idea worked well and continued to improve; the first versions of the modern AC-130 were later deployed in Vietnam. AC-130 aircraft were used, most heavily, against the Ho Chi Minh trail. Fire control methods of the time made use of the fixed-wing gunships dangerous in close proximity to friendly forces at location that was not precisely known; Special Forces camps' position was known.

High-performance attack aircraft

Flown by the Air Force, Navy, and Marines, versions of the F-4 Phantom II were the primary high-performance aircraft used in close support. Navy and Marine A-4 Skyhawk aircraft operated in the northern areas, both from carriers and land bases.

B-52

In April 1964, GEN Westmoreland asked for the use B-52s against VC base camps. He argued that B-52s were better suited for this job than fighters and fighter-bombers, because they could efficiently deliver a wide, even pattern over a large area. [11]

In 1964, the Air Force decided to improve the B-52F's conventional bombing capability by modifying it to carry 12 standard 340 kilogram (750 pound) bombs on multiple ejector racks fitted to each Hound Dog pylon, along with the existing conventional warload of 27 bombs in the bombbay, for a total of 51 bombs.[12]

Initial operations

On 15 June, VC forces were discovered near Ben Cat at a regional headquarters 10 miles north of Saigon, and a raid was scheduled for 18 June. 27 B-52Fs left Guam to perform a tactical strike on a concentration of Viet Cong forces north of Saigon. There were significant operational problems, including a mid-air collision killing 8 of 12 crew and causing two aircraft to crash, and technical problems forced one Buff to return to base. When US-led ARVN reconnaissance teams inspected the area, they found no bodies; MACV counterintelligence later learned that the VC had been warned by a spy in the local ARVN unit. Westmoreland, however, made public comments about the weapon being extremely effective, apparently annoying the Air Staff. [13]The first Arc Light sorties targeted in response to U.S. troop requests came in November.

That was the only B-52 raid conducted in June. Five more Arc Light raids, totalling 140 B-52F sorties, were conducted in July 1965, and five more, totalling 165 sorties, took place in August. Although no B-52s were lost in these ten actions, it was difficult to get timely support, against a mobile enemy, when each mission needed White House approval.

By late August, decision-making authority for Arc Lights had been moved down slightly, to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, which simplified that issue a bit. More importantly, the Air Force had revised their tactics. Although large raids were still conducted with 30 or so Buffs, the tendency was now to commit them in smaller numbers -- eventually settling on three as more or less the norm -- and conduct raids on multiple locations simultaneously. Beginning in December 1965, B-52s also began to expand their area of operation, performing raids into Laos against logistical facilities on the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Change to radar-directed B-52D

In the South, B-52 support was originally targeted from TACAN beacons. A radar-guided drop technique was subsequently use, especially at the Battle of Khe Sanh. B-52D aircraft, intended for nuclear strike missions, were modified to maximize their ability to carry gravity bombs.[12]

The Buff gradually became an important weapon in the war, providing a form of "flying artillery" that could dump overwhelming firepower, making a profound impression on the enemy. General Westmoreland commented: "We know, from talking to prisoners and defectors, that the enemy troops fear B-52s, tactical air, artillery, and armor ... in that order."

The B-52F remained in combat service in Southeast Asia for less than a year, being replaced in March 1966 by the B-52D, which had been optimized for the role. Beginning in late 1965, all B-52Ds had been given the "high density bombing (HDB)" or "Big Belly" upgrade, which modified the aircraft to carry 84 225 kilogram (500 pound) or 42 340 kilogram (750 pound) bombs in the bombbay. The upgraded B-52Ds could also carry 24 340 kilogram bombs on the pylons, for a total maximum warload of an 27,200 kilograms (60,000 pounds) of conventional bombs.

For missions in Vietnam, the principal airfield was Anderson AFB in Guam, which took significant refueling. Advanced basing, starting on April 10, 1967, at U Tapao Royal Thai Air Base, helped the times, but did not offer more than basic B-52 maintenance.

The first radar drop guidance used the Strategic Air Command AN/MSQ-77 radar bombing scoring system, which was precise enough for such targets as airfields. By 1967, five MSQ-77's were in SVN and one in Thailand. By 1967, the Air Force had five AM/MSQ-77 radars working in South Vietnam and one in Thailand.

Medical support

Immense improvements over even Korean War field medicine, of M*A*S*H fame, were a great morale factor. [14] They involved several key factors:

- Rapid helicopter evacuation, with more advanced medical technicians, from the battlefield

- Mobile trauma hospitals a short distance from the battlefield

- Improved medical understanding of trauma management, especially aggressive prevention of shock and related respiratory conditions, rather than treating those often-lethal complications once they had developed.

"Dust Off" medical evacuation UH-1 Huey helicopters. promptly removed the wounded from the battlefield, and to an advanced trauma hospital system. Medevac runs had the highest priority, and were unusually dangerous. Two medevac pilots won the Congressional Medal of Honor for their heroism. It took on average 100 minutes to rush a casualty to the nearest field hospital. 390,000 American and ARVN casualties were medevaced. Thanks to quick hospitalization and aggressive prevention of traumatic shock and the acute respiratory distress syndrome, 82% of the seriously wounded who arrived at hospitals survived, a sharp improvement over previous wars due to helicopters, as well as significant advances in trauma management.

References

- ↑ Ewell, Julian J.; Ira A. Hunt, Jr. (1995). Vietnam Studies: Sharpening the Combat Edge: the Use of Analysis to Reinforce Military Judgment. Washington DC: US Department of the Army.

- ↑ "Igloo White", Air Force Magazine 87 (11), November 2004

- ↑ Ploger, Robert R. (1974), CHAPTER VII: Engineer Mobilization and Performance, Vietnam Studies: U.S. Army Engineers, 1965-1970, Office of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Department of the Army

- ↑ Haas, pp. 250-255

- ↑ Defence Canada, The Use of Herbicides at CFB Gagetown from 1952 to Present Day

- ↑ Haas, Michael E. (1997). Apollo’s Warriors: US Air Force Special Operations during the Cold War. Air University Press., pp. 275-277

- ↑ Galvin, John R. (1969), Air Assault: the development of airmobile warfare, Hawthorn Books

- ↑ Grau, Lester W. (May-August 1998), "The RPG-7 On the Battlefields of Today and Tomorrow", Infantry

- ↑ Richardson, Doug (February 1, 2003), "Summoning the Fire", Armada International

- ↑ Brazier, R. C. (1974), DEFEAT of the 320th, The Marines in Vietnam, 1954-1973: An Anthology and Annotated Bibliography (Second Printing, 1985 ed.), History and Museums Division, United States Marine Corps, p. 168

- ↑ Head, William P. (July 2002), "War from above the clouds: B-52 Operations during the Second Indochina War and the Effects of the Air War on Theory and Doctrine", Fairchild Paper, Air University Press, pp. 17-18

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Goebel, Greg (August 1, 2007), [2.0 B-52 At War]

- ↑ Head 2002, pp. 19-20

- ↑ Neel, Spurgeon (1991), Vietnam Studies: Medical Support of the U.S. Army in Vietnam 1965-1970, Center for Military History, U.S. Department of the Army