Battle of Leyte Gulf

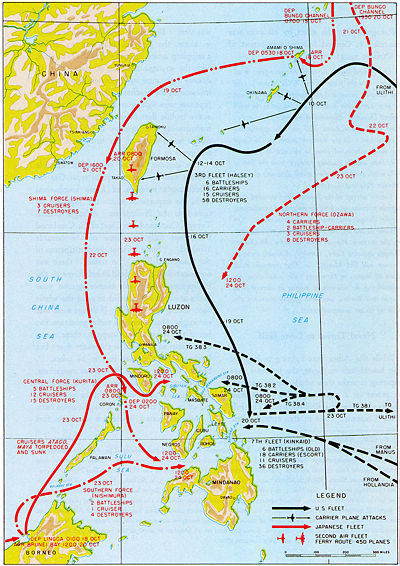

The Battle of Leyte Gulf in October 23-26, 1944, was the largest naval battle in world history, in terms of total combatant personnel and firepower. It was fought in the seas around and to the east of the Philippine Islands between the Japanese Imperial Navy and Allied naval forces. The bulk of naval combat took place after the initial troop landings on the island of Leyte.

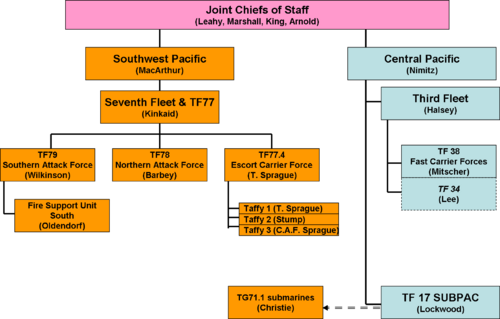

Both sides suffered from divided command. The only joint commanders were in Washington and Tokyo.

American situation

U.S. Pacific strategy derived from Joint Chiefs of Staff decisions at the Cairo Conference (1943), to obtain "bases from which the unconditional surrender of Japan can be forced."[1] There was, however, little clarity and much argument among the JCS and the two theater commanders, Douglas MacArthur for the Southwest Pacific Area and Chester Nimitz for the [Central] Pacific and Pacific Ocean Areas. JCS guidance to Nimitz and MacArthur, dated 12 March 1944, reflected what was to become an obsolete concept: "The JCS has decided that the most feasible approach to Formosa, Luzon and China is by way of the Marianas, Luzon and China."

Events were to make Formosa, Luzon and China infeasible as the final bases for attacks on the Japanese home islands. In May 1944, the Japanese Army, moved into Eastern China. After this, the JCS suggested considering bypassing all the intermediate bases and directly attacking Kyushu, the target, much later, of Operation OLYMPIC. This suggestion outraged MacArthur, but it reflected the desire of Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall not to embark on unnecessary land campaigns;[2] Marshall had also been an advocate of a very early cross-Channel invasion in the European theater.

Concept of operations

MacArthur had a deep emotional bond to the Phillipines, and both believed the honor of the United States required their liberation and that such an approach was strategically sound. He saw Leyte as the base from which the rest of the Phillipines could be taken. [3]

Staff of Halsey and Nimitz agreed on three naval operations in support:[4]

- Air strikes on Okinawa, Formosa, and Northern Leyte on 10-13 October, by Third Fleet and long-range land-based aircraft

- Attacks on Bicol Peninsula, Leyte, Cebu and Negros, and direct supports of the actual landings, 16-20 October; this was the Seventh Fleet role

- "Strategic support" from 21 October onwards. This was the principal Third Fleet role, and an ambiguous one

Command structure

United States Third Fleet under Admiral William Halsey reported to Admiral Chester Nimitz, and had the roles of defeating the major Japanese fleet and taking the islands of the Central Pacific. To increase the tempo of operations, the same ships were Third Fleet when under Halsey and his staff, and Fifth Fleet when under Admiral Raymond Spruance. Spruance and Halsey, without friction, alternated in planning and executing operations.

The Joint Chiefs in Washington had never been able to agree on a single commander for the Pacific. Nevertheless, the Third and Seventh Fleets were standing organizations that had reasonable internal communications.

Seventh Fleet mission

Under MacArthur, the Seventh Fleet, commanded by Vice Admiral Thomas Kinkaid (commander, Allied Naval Forces, Southwest Pacific Area) had the mission of landing and supporting the landing force. [5] Although code names were less frequently used to describe Pacific operations, the Seventh Fleet plan was designated Operation MUSKETEER/Operation KING V. Kinkaid's flagship was the amphibious command ship USS Wasatch (AGC-9), where he was accompanied by the Commander of the Sixth United States Army, Lieutenant General Walter Krueger. Kinkaid's deputy, VADM Thomas Wilkinson, was on the secondary flagship, command ship USS Olympus (AGC-8), which also commanded the Southern Attack Force. MacArthur's seagoing headquarters was on the cruiser USS Nashville.

Northern Attack Force, under RADM Daniel Barbey aboard USS Blue Ridge (AGC-2), was to land the X Army Corps under MG F.C. Sibert.

Southern Attack Force carried XXIV Army Corps under MG J.R. Hodge. Transport task groups carried divisions. Fire Support Unit South was made up of old battleships and other heavy gunships under RADM Jesse Oldendorf, and TG 77.4, the Escort Carrier Group, was under RADM Thomas Sprague.

Third Fleet mission

There was much more ambiguity in the mission of Vice Admiral William Halsey's Third Fleet. Nimitz directed him to "cover and support" SWPA forces "in order to assist in the seizure of all objectives in the Central Phillipines", and to "destroy enemy naval and air forces in or threatening the Phillippines area." This was consistent with orders given to Spruance's Fifth Fleet in the Marianas operation.

An additional paragraph, which may have been added by the staff, said

In case opportunity for destruction of major portion of the enemy fleet is offered or can be created, such destruction becomes the primary task.

Halsey, more aggressive than his friend Spruance, interpreted that in his own operation order: "If opportunity exists or can be created to destroy major portion of the enemy fleet, this becomes primary task.[6] This is the classic Mahanian goal, shared by Halsey's opponents, especially VADM Takeo Kurita. Halsey's decisions remain active arguments among naval historians, although more tend to believe he lost sight of the most important mission.[7]

Confusion about Third Fleet organization, however, was not restricted to Halsey's command. VADM Willis Lee held the dual roles of Commander, Battleships, Pacific Fleet, and head of a Third Fleet organization called Task Force 34. During the Battle of Leyte Gulf, TF 34 was never organized as a single surface battle force, although Lee exerted coordination over the heavy gunfire ships distributed to the carrier task groups. Both Nimitz and Kinkaid, however, were uncertain if TF 34 was operating as a single unit, generally assuming that it was, and called for Lee's assistance during the Action off Samar.[8] Lee might have formed TF 34 as Battle Line had Halsey engaged Ozawa's force with a surface gunfire action, but, as a result of the problems in San Bernadino Strait, Halsey called off that action.

Confusion between Halsey and Kinkaid, including Halsey's priority of attacking the Japanese carrier force, led to San Bernadino Strait not being covered and the Action off Samar decided by the desperate fighting of light vessels of the Seventh Fleet. See the Action off Samar for details of communications and miscommunications.

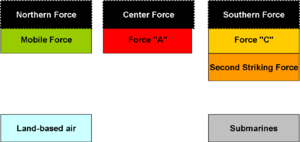

Japanese situation

As with the U.S. forces, the only common command was at the national capital. Admiral Soemu Toyoda directed a number of units, which had extremely poor coordination — even rivalry — with one another.

The U.S., however, did not understand either the actual Japanese organization, or that the Mobile Force's role was that of a sacrificial decoy.

Concept of operations

At first, the Japanese concept of Operation SHO-GO sought the Mahanian "decisive battle" of major fleet units. A series of SHO-GO operational plans were developed by Imperial General Headquarters (IGHQ) and Combined Fleet, with contingencies for the invasion coming at Luzon, or the central or southern Phillipines. IGHQ developed policy and Combined Fleet issued the operational orders. [9]

Circumstances affected the specific operational intent. Rear Admiral Toshitane Takata, who had been a senior staff officer of a fleet, Combined Fleet, and the General Staff, felt that it was a reasonably good plan, but broke down especially after U.S. airstrikes on in the Phillipines in September, and later on Formosa, cost the Japanese too many land-based aircraft. He also said there was no intention to combine Kurita's and Ozawa's forces, based in the Inland Sea and Lingga. "There was such a desire but it was impossible to do that because of shortage of fuel and personnel...

Command structure

The U.S. had a poor understanding of the Japanese command structure, sometimes looking for complex strategic reasons when the positioning of a unit was simply due to fuel supply. MacArthur's Air Evaluation Board after the war, "Enemy intentions rather than capabilities were prominent [in U.S. planning]]." [10]

Mobile Fleet

The carrier-centric Mobile Fleet, under Vice Admiral Jizaburo Ozawa, had stayed in the Inland Sea of Japan, training new air groups. Due to its proximity to Combined Fleet, and the high regard in which Ozawa was held, even by his American interrogators after the war, he was an important adviser to Toyoda.

Still, Ozawa had limited authority and information. When asked if he knew who commanded the U.S. forces, he replied "I do not remember who I thought was your commander in chief at that time; there was at the time some estimate but I do not remember. " He said he did not know about kamikaze plans until "The first time I heard of Kamikaze attacks was when Kyrita's fleet went through San Bernadino Strait. I knew that Kamikaze attack was coming from Manila Area [i.e., land-based air under Mizawa, Ohnishi and Fukodome] to oppose the Leyte landing. "[11]

First Striking Force

Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita, was in overall command of the First Striking Force. It was based in Lingga Roads, near Singapore, to be near its fuel supply. Coincidentally, Lingga Roads was closer to India, and the British interpreted this as a threat to it, which led them to hold forces there. [12] Whether this really kept British contributions out of the U.S. Pacific Fleet is debatable, since Admiral Ernest King, U.S. Chief of Naval Operations, was anti-British and was reluctant to include their forces under any conditions.

Interrogated by the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey in 1945, Kurita was described as "somewhat on the defensive, giving only the briefest of replies prior to the discussion of [the Leyte campaign actions]. In some instances his memory for details such as times, cruising dispositions, etc. appeared to be inaccurate." [13] In a 1977 interview, however, he said he chose not to pass through San Bernadino Strait and attack the transports.

What had we come this far for? Bringing so many ships, and also losing so many ships - wasn't it in order to win a victory at Leyte? I thought that, if the reported task force was 30 miles north east of us, we could definitely catch it. I thought it went without saying to steer towards the enemy force that was stronger.... After all, what lay to the south of us was just a collection of soldiers.... Naval war consists of warships sinking warships. Transport shipping is an opponent for land forces to deal with, isn't it? [14]

Vice Admiral Shigeo Nishimura, commanding Force C of the First Striking Force, was a respected "sea dog", unusual in never having served in a shore command and having passed the exams, but not taken the Staff College course. [15]

Second Striking Force mission

The Second Striking Force was made up of cruisers and destroyers, under VADM Kiyohido Shima. As opposed to Nishimura, Shima had spent much of his career in administrative posts. Thomas Cutler speculates that one reason not to merge the forces was that the less combat-experienced Shima was senior to Nishimura.[16] Shima and Mizawa fought over authority. [17]

Land-based aviation

Submarines

The battle

By the time landings had started, the most crucial Japanese objective was to attack the transports and other Seventh Fleet ships. They planned a two-pronged attack, through Surigao Strait and through San Bernadino Strait; the latter passes Samar. Their main body was Kurita's Force A within the First Striking Force. Two uncoordinated forces were to try to approach through Surigao Strait, Nishimura's Force C and Shima's Second Striking Force. Meanwhile, Ozawa was to continue acting as a decoy to divert Third Fleet away from the Japanese attack forces.

Japanese scouting

American forces shot down a Japanese scout plane on the 20th. Unknown to the U.S., it was looking for kamikaze targets, but probably due to poor communications, the Japanese did not start coordinated kamikaze operations. They managed a single attack on the 21st, damaging the cruiser HMAS Australia.[18]

The Fight in Palawan Passage

On 23 October, Japanese Center Force was sighted by U.S. patrol submarines, USS Darter and USS Dace, in Palawan Passage. After reporting it to higher headquarters, USS Darter and USS Dace torpedoed three heavy cruisers, sinking two and damaging a third such that it had no additional role in the war. The first, IJN Atago, was Admiral Kurita's flagship; Rear Admiral Ugaki took temporary command until Kurita was rescued by a destroyer, [19]

This was the first of several shocks to Kurita, which may have affected his later judgment. It was also a key intelligence datum to the U.S. command.

Battle of the Sibuyan Sea

Vice Admiral Willis Lee was Commander, Battleships, Pacific Fleet, and wore the "second hat" of commanding Task Force 34 (battleships) of Third Fleet. TF 34, however, never operated independently; Lee's reports collated information from battleships and other heavy surface combatants operating with the fast carrier groups. They reported finding a Japanese force on the morning of the 24th.[20]

In this action, Third Fleet indeed sank the superbattleship IJN Musashi.

Battle of Surigao Strait

Equipped with superb optics, the Japanese began the war ruling night action. The Allied development of radar, however, neutralized this advantage, but the Japanese often still preferred stealth by night.

The Japanese forces under Admirals Nishimura and Shima had no common command, minimal coordination, and were too far apart for mutual suport. Nishimura's stronger force came first, and all but one destroyer, IJN Shigure, sunk. Forces in Surigao Strait were an afterthought. "Admiral Shima's fleet happened to be there at the same time. In order to get to Leyte they decided to combine. It was not originally planned that Admiral Shima's force should take part in this southern action. It happened only by a series of coincidences that he was first ordered to Okinawa, then to Manila by Bako to attack your force but found it impossible; and so while en route to Manila he was given orders to follow Admiral Nishimura's force in an attempt on Leyte Gulf. This was truly an appendix to our plan.[9]

Action off Samar

Sometimes called the Battle of San Bernadino Strait, the Action off Samar describes the improvised and successful American defense against Kurita's Force A, which was attempting to break into Leyte Gulf. While his Force A had lost combat power in the preliminaries and the Battle of the Sibuyan Sea, it was still an immensely powerful gunfire force that could devastate the transports and support vessels in Leyte Gulf.

Until an antisubmarine patrol aircraft sighted the Japanese force, Admiral Kinkaid, commanding Seventh Fleet assumed/ that Third Fleet forces were guarding the San Bernardino Straits in position to intercept and destroy any enemy forces attempting to come through. "To confirm this assumption, Commander Seventh Fleet had sent a dispatch to the Commander Third Fleet asking if he was guarding the San Bernardino Straits. Reply was not received until after the enemy surface forces were attacking our Northern CVE Group. "[21]

Organized Kamikaze operations

Battle of Cape Engano

On the 24th, Ozawa launched an air strike against Halsey, more to get his attention than expecting to do serious damage. After the survivors returned, he formed a surface Advanced Guard under RADM Masuda, to "divert the enemy" in support of Kurita's main effort. Initially delighted when he intercepted messages from U.S. search planes, he thought he finally had attracted Halsey.

On learning that Kurita had reversed course after the Action off Samar, Ozawa concluded that Operation SHO-GO had failed, and turned north to save what he could. An hour later, Combined Fleet ordered Ozawa to resume his attack. He recalled Masuda to join his main force.[22]

Halsey, who believed the Japanese carriers were the principal Third Fleet objective, brought them under attack on October 25 and 26.

Outcome

By 1944, and even after the Battle of Pearl Harbor, it was obvious that aircraft and the aircraft carrier had replaced the battleship as the decisive factor in major naval combat. At the Battle of the Phillipine Sea, fought before Leyte Gulf, Japanese naval aviation was essentially destroyed — aircraft carriers without skilled pilots are useless.

Leyte Gulf, however, effectively destroyed the Imperial Japanese Navy as a surface force. Of the 282 warships engaged (216 American, 2 Australian, and 64 Japanese), the Japanese lost 4 carriers, 3 battleships, 10 cruisers, and 11 destroyers. American losses totaled one light carrier, two escort carriers, and three destroyers.

Halsey always defended his decision to abandon Leyte; its defense was Kinkaid's job and his mission was strategic.

Japan did not effectively defend the Phillipines. It has been reported that Emperor Hirohito refused the operational decision of the able field commander, General Tomiyuki Yamashita, who had wanted to make his stand on Luzon, not Leyte. The Emperor said,

Contrary to the views of the Army and Navy General Staffs, I agreed to the showdown battle of Leyte thinking that if we attacked at Leyte and America flinched, then we would probably find room to negotiate. [23]

References

- ↑ Samuel Eliot Morison (1970), History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, vol. Volume XII: Leyte, June 1944-January 1945, Atlantic Monthly/Little, Brown, p. 4

- ↑ Morison, pp. 5-7

- ↑ , Chapter VIII, The Leyte Operation, Reports of General MacArthur: The Campaigns of MacArthur in the Pacific, Office of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Army, 1966

- ↑ Morison, p. 57

- ↑ MUSKETEER/KING V CANF SWPA - OPERATION PLAN 13-44, U.S. Navy, 26 December 1944

- ↑ Com Third Fleet Operation Order 21-44 of 3 Oct., quoted by Morison, p. 58

- ↑ Kent S. Coleman (2006), Thesis Title: Halsey at Leyte Gulf: Command Decision and Disunity of Effort, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College

- ↑ William F. Halsey with J. Bryan, Admiral Halsey's Story (1947) pp. 220-1

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Interrogation of: Rear Admiral TAKATA, Toshitane,IJN; attached successively to the Staff of the Third Fleet, the Combined Fleet, and the Naval General Staff.", U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, 1 November 1945, INTERROGATION NAV NO. 64/USSBS NO. 258 (Japanese Naval Planning after Midway)

- ↑ Morison, p. 74

- ↑ "Interrogation of Admiral Ozawa, Jisaburo, task force commander in the Leyte operation", U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, 30 October 1945, Interrogation No. 55

- ↑ Morison, p. 5

- ↑ "KURITA, Takeo, Vice Admiral, I.J.N.", U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey Interrogation of Japanese Officials, Interrogation No. 90

- ↑ C. Peter Chen, "Takeo Kurita", World War II database

- ↑ Anthony P. Tully (2009), Battle of Surigao Strait, Indiana University Press, pp. 30-34

- ↑ Thomas J. Cutler (2001), The Battle of Leyte Gulf: 23-26 October 1944, Naval Institute Press, pp. 95-96

- ↑ Tully, pp. 20-21

- ↑ Edward P. Hoyt (1983), The Kamikazes, Burford Books, ISBN 1580800319, pp. 59-64

- ↑ Morison, pp. 169-174

- ↑ Willis Lee (14 December 1944), Report of Operations of Task Force THIRTY-FOUR During the Period 6 October 1944 to 3 December 1944., U.S. Navy

- ↑ Thomas Kinkaid, commanding Task Force 77 (18 November 1944), Preliminary Action Report of Engagements in Leyte Gulf and off Samar Island on 25 October, 1944, Hyperwar Foundation

- ↑ Morison, pp. 317-321

- ↑ Herbert Bix (2000), Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, HarperCollins, ISBN 006019314X, pp. 481-482

- Pages using ISBN magic links

- CZ Live

- History Workgroup

- Military Workgroup

- World War II Subgroup

- Pacific War Subgroup

- United States Navy Subgroup

- Articles written in American English

- Advanced Articles written in American English

- All Content

- History Content

- Military Content

- History tag

- Military tag

- World War II tag

- Pacific War tag

- United States Navy tag