Horse: Difference between revisions

imported>Nancy Sculerati MD No edit summary |

imported>Nancy Sculerati MD |

||

| Line 94: | Line 94: | ||

Horses were used in warfare for most of recorded history, dating back at least to the 19th century B.C. While mechanization largely has replaced the horse as a weapon of war, horses are still seen today in limited military uses, mostly for ceremonial purposes, or for reconnaissance and transport activities in areas of rough terrain where motorized vehicles are ineffective. Horses are also used to reenact historical battles; see Culture above. The training of the [[war horse]] has vestiges in the disciplines of [[classical dressage]] and [[eventing]]. | Horses were used in warfare for most of recorded history, dating back at least to the 19th century B.C. While mechanization largely has replaced the horse as a weapon of war, horses are still seen today in limited military uses, mostly for ceremonial purposes, or for reconnaissance and transport activities in areas of rough terrain where motorized vehicles are ineffective. Horses are also used to reenact historical battles; see Culture above. The training of the [[war horse]] has vestiges in the disciplines of [[classical dressage]] and [[eventing]]. | ||

==Specialized vocabulary== | ==Specialized vocabulary== | ||

Revision as of 12:54, 12 December 2006

| Domestic Horse | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| Conservation status | ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Binomial name | ||||||||||||||

| Equus caballus Linnaeus, 1758 |

Horses are not just one of the oldest species of animals ever domesticated, but have changed the course of human history through their association with mankind. Although other animals have also been our beasts of burden, and served to move us over the land before technology provided us with machines; it is the hooves of horses that thundered under the hordes of Ghengis Khan and the Spanish Conquistadors, and the While isolated domestication may have occurred as early as 10,000 years ago,the first clear evidence of widespread horse use by humans dates to around 2000 BC. Since they were domesticated, selective breeding has resulted in many breeds. Some have been bred so that they can be ridden, usually with a saddle, while other breeds can be harnessed to pull objects like carriages or plows. In some cultures, horses are a source of food, including horse meat and sometimes milk; in other cultures it is taboo to eat them. Today, in wealthy countries, horses are predominantly kept for leisure and sporting pursuits, while they are still used as working animals in less developed parts of the world.

Biology of the horse

- See also: Horse reproduction

Depending on breed, management, and environment, the domestic horse today has an average life expectancy of 25 to 30 years. A rare few domestic horses can live into their 40s, and, occasionally, beyond. The oldest verifiable record was "Old Billy," a horse that lived in the 19th century, believed to have lived to the age of 62.

Pregnancy lasts for 11 months and usually results in one foal (male: colt, female: filly). Twins are rare. Horses, particularly colts, may sometimes be physically capable of reproduction at approximately 18 months but in practice are rarely allowed to breed until a minimum age of 3 years, especially females. Horses four years old are considered mature, though the age of achieving full growth also varies by breed and by individual genetics. Females 4 years and over are called mares and males are stallions. A castrated male is a gelding.

Depending on maturity, breed and the tasks expected, young horses are usually put under saddle and trained to be ridden between the ages of two and four, with three years being the most common practice. Although Thoroughbred and American Quarter Horse race horses are put on the track at as young as two years old in some countries (notably the United States), horses specifically bred for sports such as show jumping are generally not entered into top-level competition until the age of five or six because their bones and muscles are not properly developed, nor is their training complete. In the strenuous sport of endurance riding, horses are not allowed to compete until they are a full 60 months (five years) old. In some cases, such as the training of Andalusians or Lipizzans in classical dressage, training under saddle begins as late as four years and the horses are not considered ready for public performance until the age of nine or ten.

The size of horses varies by breed. The cutoff in height between what is considered a horse and a pony is always 14.2 or smaller hands (58 inches, 145 cm), though some smaller horse breeds are considered "horses" regardless of height. Light horses such as Arabians, Morgans, Quarter Horses, Paints and Thoroughbreds usually range in height from 14.0 to 17.0 hands and can weigh up to 1300 lb (about 600 kg). Heavy or draft horses such as the Clydesdale, Belgian, Percheron, and Shire are usually at least 16.0 to 18.0 hands high and can weigh up to 2000 lb (about 900 kg). Ponies are no taller than 14.2 hands, but can be much smaller, down to the Falabella or Shetland, which can be the size of a large dog. The miniature horse is as small as or smaller than either of the aforementioned ponies but are considered to be very small horses rather than ponies despite their size. The difference between a horse and pony is not just a height difference. They have different temperaments, different conformation, and ponies often exhibit thicker manes, tails and overall hair coat.

Evolution of the horse

Horses and other equids are odd-toed ungulates of the order Perissodactyla, a relatively ancient group of browsing and grazing animals that first arose less than 10 million years after the dinosaurs became extinct. In the past, this order contained twelve families, but only three families—the horses and related species, tapirs and rhinoceroses—have survived till today. The earliest equids (belonging to the genus Hyracotherium) were found approximately 54 million years to the Eocene period. The Perissodactyls were the dominant group of large terrestrial browsing animals until the Miocene (about 20 million years ago), when even-toed ungulates, with stomachs better adapted to digesting grass, began to out compete them.

The horse as it is known today adapted by evolution to survive in areas of wide-open terrain with sparse vegetation, surviving in an ecosystem where other large grazing animals, especially ruminants, could not. [1]

Horse evolution was characterized by a reduction in the number of toes, from five per foot, to three per foot, to only one toe per foot (late Miocene 5.3 million years ago); essentially, the animal was standing on tiptoe. One of the first true horse species was the tiny Hyracotherium, which had 4 toes on each front foot (missing the thumb) and 3 toes on each back foot (missing toes 1 and 5). Over about five million years, this early equids evolved into the Orohippus. The 5th fingers vanished, and new grinding teeth evolved. This was significant in that it signaled a transition to improved browsing of tougher plant material, allowing grazing of not just leafy plants but also tougher plains grasses. Thus the proto-horses changed from leaf-eating forest-dwellers to grass-eating inhabitants of the Great Plains.

By the Pleistocene era, as the horse adapted to a drier, prairie environment, the 2nd and 4th toes disappeared on all feet, and horses became bigger. These side toes were shrinking in Hipparion and have vanished in modern horses. All that remains are a set of small vestigial bones on either side of the cannon (metacarpal or metatarsal) bone, known informally as splint bones, which are a frequent source of splints, a common injury in the modern horse.

Domestication of the horse and surviving wild species

Competing theories exist as to the time and place of initial domestication. The earliest evidence for the domestication of the horse comes from Central Asia and dates to approximately 4,500 BC. Archaeological finds such as the Sintashta chariot burials provided unequivocal evidence that the horse was definitely domesticated by 2000 BCE.

Wild species

Most "wild" horses today are actually feral horses, animals that had domesticated ancestors but were themselves born and live in the wild, often for generations. However, there are also some truly wild horses whose ancestors were never successfully domesticated.

Historical wild species include the Forest Horse (Equus ferus silvaticus, also called the Diluvial Horse), thought to have evolved into Equus ferus germanicus, and may have contributed to the development of the heavy horses of northern Europe, such as Ardennais.

There is a theory that there were additional "proto" horses that developed with adaptations to their environment prior to domestication. There are competing theories, but in addition to the Forest Horse, three other types are thought to have developed:[2]

- A small, sturdy, heavyset pony-sized animal with a heavy hair coat, arising in northern Europe, adapted to cold, damp climates, somewhat resembling today's Shetland pony

- A taller, slim, refined and agile animal arising in western Asia, adapted to hot, dry climates, thought to be the progenitor of the modern Arabian horse and Akhal-Teke

- A dun-colored, sturdy animal, the size of a large pony, adapted to the cold, dry climates of northern Asia, the predecessor to the Tarpan and Przewalski's Horse.

The tarpan, Equus ferus ferus, became extinct in 1880. Its genetic line is lost, but its phenotype has been recreated by a "breeding back" process, in which living domesticated horses with primitive features were repeatedly interbred. Thanks to the efforts of the brothers Lutz Heck (director of the Berlin zoo) and Heinz Heck (director of Munich Tierpark Hellabrunn), the resulting Wild Polish Horse or Konik more closely resembles the tarpan than any other living horse.

Przewalski's Horse (Equus ferus przewalskii), a rare Asian species, is the only true wild horse alive today. Mongolians know it as the taki, while the Kirghiz people call it a kirtag. Small wild breeding populations of this animal, named after the Russian explorer Przewalski, exist in Mongolia. [3] There are also small populations maintained at zoos throughout the world.

Other truly wild equids alive today include the zebra and the onager.

Feral horses

Wild animals, whose ancestors have never undergone domestication, are distinct from feral ones, who had domesticated ancestors but were born and live in the wild. Several populations of feral horses exist, including those in the western United States and Canada (often called "mustangs"), and in parts of Australia ("brumbies") and New Zealand ("Kaimanawa horses"). Isolated feral populations are often named for their geographic location: Namibia has its Namib Desert Horses; the Sorraia lives in Portugal; Sable Island Horses reside in Nova Scotia, Canada; and New Forest ponies have been part of Hampshire, England for a thousand years.

Studies of feral horses have provided useful insights into the behavior of ancestral wild horses, as well as greater understanding of the instincts and behaviors that drive "tame" horses.

Horse behavior

Horses are prey animals with a well-developed Fight-or-flight instinct. Their first response to threat is to flee, although they are known to stand their ground and defend themselves or their offspring in cases where flight is not possible, such as when a foal would be threatened. Through selective breeding, some breeds of horses have been bred to be quite docile, particularly certain large draft horses. However, most light horse riding breeds were developed for speed, agility, alertness and endurance; natural qualities that extend from their wild ancestors.

Horses are herd animals, and become very attached to their species and to humans. They communicate in various ways, such as nickering, grooming, and body language. Some horses will become flighty, and hard to manage if they are away from their herd. This is called being "herd-bound."

Horses used for therapeutic purposes

A form of physical therapy is Therapeutic horseback riding. People with both physical and mental disabilities have obtained medically beneficial results from riding. The movement of a horse strengthens muscles throughout a rider's body and promotes better overall health. In many cases, riding has also led to increased mobility for the rider and sometimes has helped injured people regain the ability to walk. Soldiers injured in warfare have been known to use this form of physical therapy to regain movement in limbs or simply become accustomed to prosthetic limbs. People who have cognitive or sensory disabilities benefit because riding requires attention, reasoning skills and memory. Template:Fact

The benefits of equestrian activity for people with disabilities has also been recognized with the addition of equestrian events to the Paralympic Games.

"Equine-assisted" or "equine-facilitated" psychotherapy is a new but growing movement which uses horses as companion animals to assist people with mental illness. Actual practices vary widely due to the newness of the field; some programs include therapeutic riding. Non-riding therapies simply encourage a person to touch, speak to and otherwise interact with the horse. Even without riding, people appear to benefit from being able to connect to a horse on a personal level. People with mental illnesses can benefit from the interaction and relationships formed with both horses and people. Horses are also used in camps and programs for young people with emotional difficulties.Template:Fact

There also have been experimental programs using horses in prison settings. Exposure to horses appears to improve the behavior of inmates in a prison setting and help reduce recidivism when they leave. A correctional facility in Nevada has a successful program where inmates learn to train young mustangs captured off the range in order to make it more likely that these horses will find adoptive homes. Both adult and juvenile prisons in New York, Florida, and Kentucky work in cooperation with the Thoroughbred Retirement Foundation to re-train former racehorses as pleasure mounts and find them new homes.Template:Fact

Horses in warfare

Horses were used in warfare for most of recorded history, dating back at least to the 19th century B.C. While mechanization largely has replaced the horse as a weapon of war, horses are still seen today in limited military uses, mostly for ceremonial purposes, or for reconnaissance and transport activities in areas of rough terrain where motorized vehicles are ineffective. Horses are also used to reenact historical battles; see Culture above. The training of the war horse has vestiges in the disciplines of classical dressage and eventing.

Specialized vocabulary

Because horses and humans have lived and worked together for thousands of years, an extensive specialized vocabulary has arisen to describe virtually every horse behavioral and anatomical characteristic with a high degree of precision.

In horse racing the definitions of colt, filly, mare, and horse may differ from those given above. In the United Kingdom, thoroughbred racing defines a colt as a male horse less than five years old and a filly as a female horse less than five years old; harness racing defines colts and fillies as less than four years old. Females older than colts and fillies become known as mares, while males become stallions (non-castrated) or geldings (castrated).

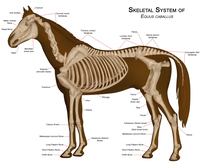

The anatomy of the horse comes with a large number of horse specific terms.

Horses exhibit a diverse array of coat colors and distinctive markings, and a specialized vocabulary has evolved to describe them. Often, one will refer to a horse in the field by its coat color rather than by breed or by sex. The genetics of the coat colors has largely been resolved, although discussion continues about some of the details.

The English-speaking world measures the height of horses in hands. One hand is defined in British law as 101.6 mm, a figure derived from the previous measure of 4 Imperial inches. Horse height is measured at the highest point of an animal's withers. Perhaps because of extensive selective breeding, modern adult horses vary widely in size, ranging from miniature horses measuring 5 hands (0.5 m) to draft animals measuring 19 hands (1.8 m) or more. By convention, 15.2 hh means 15 hands, 2 inches (1.57 m) in height.

Horses versus ponies

Ponies are smaller than horses and stay that way through their lives. In general, to be a pony the equine in question must stand 14.2hh or lower at the withers. Many breeds do not grow bigger than this measurement of size, and part of the breed characteristics is pony. Therefore, any equine in that breed must be pony sized to be registered. Ponies also tend to have certain conformational characteristics: they tend to be stockier than horses, have shorter legs, wide barrels, and thick necks and heads.

There are exceptions to this general rule. Some breeds are pony sized, but called horses. Examples include the caspian horse which often stands only eleven or twelve hands, but it has the conformation of a horse – refined head, clean legs and fine bones – rather than that of a pony. Other breeds, such as the Pony of the Americas or the Welsh cob, share some features of horses but are still considered ponies.

Gaits

All horses move naturally with four basic gaits; these are referred to as walk, trot ("English") or jog ("Western"), canter ("English") or lope ("Western"), and gallop.

Besides these basic gaits, additional gaits such as pace, slow gait, rack, fox trot and tölt can be distinguished. These special gaits are often found in specific breeds, and are referred to as "gaited" because they naturally possess additional "single-footed" gaits that are approximately the same speed as the trot but smoother to ride. Technically speaking the so called "gaited horses" replace the standard trot which is a 2 beat gait with a four beated gait. (as opposed to the canter/lope and gallop which are three beated gaits) This can be clearly heard when shod horses are riding on the street. The anatomy of the trot consists of the lifting a front hoof and a rear opposite sided hoof at the same time. This can be seen vividly when watching lippizaners on parade, and is similar to a dog's trot. A four beated gait occurs when only one foot at a time lifts off, and hence is called a "running walk". In a manner of speaking this is like the front legs being operated independently of the rear. A true gaited horse will rarely, if ever, trot; gaited horse foals will gait from birth. A pace is a two beat gait where the animal moves the front and rear legs of one side at the same time, similar to an elephant. This produces a ride that is not as jarring up and down as a trot but has a definite side to side or rocking motion, this is considered an undesireable gait by people in the gaited horse trade.

A trot is an up and down action of the legs whereas the true gaited horse generally has some sort of circular motion to the front hooves (either a somewhat exaggerated forward circle, or in the case of the paso fino an outward winging motion from the knee down) and a sliding or shuffling motion to the rear hooves, when done perfectly this produces a gait that is as fast and oftentimes faster than a trot and smooth enough that the rider feels as though in an easy chair. Through training a gaited horse may effectively be rendered a 3 gaited horse with only the walk, the special gait (running walk, rack, foxtrot, etc), and the gallop. This does not diminish the speed of the horse, the animal just has no need to lope/canter due to the speed that it can perform its' special gait.

Horse breeds with additional gaits include the Tennessee Walking Horse with its running walk, the American Saddlebred with its "slow gait" and rack, the Paso Fino horse with the paso corto and paso largo and Icelandic horse which are known for the tölt. The Fox Trot is found in several gaited breeds, most notably the Missouri Foxtrotter while some Standardbreds, pace instead of trot.

The origin of modern horse breeds

Horses come in various sizes and shapes. The draft breeds can top 19 hands (76 inches, 2 metres) while the smallest miniature horses can stand as low as 5.2 hands (22 inches, 0.56 metres). The Patagonian Fallabella, usually considered the smallest horse in the world, compares in size to a German Shepherd Dog.

Different schools of thought exist to explain how this range of size and shape came about. One school, which we can call the "Four Foundations," described in the domestication section above, suggests that the modern horse evolved from multiple types of early domesticated pony and early domesticated horse; the differences between these types account for the differences in type of the modern breeds. A second school -- the "Single Foundation" -- holds only one breed of horse underwent domestication, and it diverged in form after domestication through human selective breeding (or in the case of feral horses, through ecological pressures). This question will most likely only be resolved once geneticists have finished evaluating the horse genome, analyzing DNA and mitochondrial DNA to construct family trees. See: Domestication of the horse.

In either case, modern horse breeds developed in response to the need of "form to function;" that is, the necessity to develop certain physical characteristics necessary to perform a certain type of work. Thus, light, refined horses such as the Arabian horse or the Akhal Teke developed in dry climates to be fast and with great endurance over long distances, while the heavy draft horse such as the Belgian developed out of a need to pull plows. Ponies of all breeds developed out of a dual need to create mounts suitable for children as well as for work in small places like mine shafts or in areas where there was insufficient forage to support larger draft animals. In between these extremes, horses were bred to be particularly suitable for tasks that included pulling carriages, carrying heavily-armored knights, jumping, racing, herding other animals, and packing supplies.

The Icelandic horse (pony-sized but called a horse) provides an opportunity to compare contemporary and historical breed appearances and behavior. Introduced by the Vikings into Iceland over one thousand years ago, these horses did not subsequently undergo the intensive selective breeding that took place in the rest of Europe from the Middle Ages onwards, and consequently bear a closer resemblance to pre-Medieval horses. The Icelandic horse is of small stature and has a four-beat gait called the "tolt", similar to the rack of the American Saddlebred.

Some countries specialize in breeding horses suitable for particular activities. For example, Australia, the United States, and the Patagonia region of South America are known for breeding horses particularly suitable for working cattle and other livestock. Germany produces Holsteiner and other Warmblood breeds that are used for dressage. Ireland is recognized for breeding hunters and jumpers. Spain and Portugal are known for the "Iberian horses", Andalusians (Pura Raza Espanola) and Lusitanos, used in high school dressage and bullfighting. Austria is known worldwide for its Lipizzaner horses, used for dressage and high school work in the famous Spanish Riding School in Vienna. The United Kingdom breeds an array of heavy draft horses and several breeds of hardy ponies, including the Dartmoor pony, Exmoor pony and Welsh pony. Both the United States and Great Britain are noted for breeding Thoroughbred race horses. Great Britain is well known for the bay haired Shire horse breed. The United States is also known for the Morgan and Quarter horse breeds. Russia takes great pride in breeding harness racing horses, a tradition dating back to the development of the Orlov Trotter in the 18th century.

Breeds, studbooks, purebreds, and landraces

Selective breeding of horses has occurred as long as humans have domesticated them. However, the concept of controlled breed registries has gained much wider importance during the 20th century. One of the earliest formal registries was General Stud Book for thoroughbreds[4], a process that started in 1791 tracing back to the foundation sires for that breed. These sires were Arabians, brought to England from the Middle East.

The Arabs had a reputation for breeding their prize Arabian mares to only the most worthy stallions, and kept extensive pedigrees of their "asil" (purebred) horses. Though these pedigrees were primarily transmitted via an oral tradition, written pedigrees of Arabian horses can be found that date to the 14th century. During the late Middle Ages the Carthusian monks of southern Spain, themselves forbidden to ride, bred horses which nobles throughout Europe prized; the lineage survives to this day in the Andalusian horse or caballo de pura raza espanol.

The modern landscape of breed designation presents a complicated picture. Some breeds have closed studbooks; a registered Thoroughbred, Arabian, or Quarter Horse must have two registered parents of the same breed, and no other criteria for registration apply. Other breeds tolerate limited infusions from other breeds; for example, the modern Appaloosa must have at least one Appaloosa parent but may also have a Quarter Horse, Thoroughbred, or Arabian parent and must also exhibit spotted coloration to gain full registration.Template:Fact Still other breeds, such as most of the warmblood sport horses, require individual judging of an individual animal's quality before registration or breeding approval, but also allow outside bloodlines in if the horses meet the standard.

Breed registries also differ as to their acceptance or rejection of breeding technology. For example, all Jockey Club Thoroughbred registries require that a registered Thoroughbred be a product of a natural mating ('live cover' in horse parlance). A foal born of two Thoroughbred parents, but by means of artificial insemination or embryo transfer is barred from the Thoroughbred studbook. Any Thoroughbred bred outside of these constraints can, however, become part of the Performance Horse Registry.

On the other hand, since the advent of DNA testing to verify parentage, most breed registries now allow artificial insemination (AI), embryo transfer (ET), or both. The high value of stallions has helped with the acceptance of these techniques because they 1) allow a stallion to breed more mares with each "collection," and 2) take away the risk of injury during mating.

Hot bloods, warm bloods, and cold bloods

- See also: List of horse breeds

Horses are mammals and as such are all warm-blooded creatures, as opposed to reptiles, which are cold-blooded. However, these words have developed a separate meaning in the context of equine description, with the "hot-bloods," such as race horses, exhibiting more sensitivity and energy, while the "cold-bloods" are heavier, calmer creatures such as the draft giants.

Hot bloods Arabian horses, whether originating on the Arabian peninsula or from the European studs (breeding establishments) of the 18th and 19th centuries, gained the title of "hot bloods" for their temperament, characterized by sensitivity, keen awareness, athleticism, and energy. European breeders wished to infuse some of this energy and athleticism into their own best cavalry horses. These traits, combined with the lighter, aesthetically refined bone structure of the Arabian, was used as the foundation of the thoroughbred breed.

The Thoroughbred is unique to all breeds in that its muscles can be trained for either fast-twitch (for sprinting) or slow-twitch (for endurance), making them extremely versatile breed.Template:Fact Arabians are used in the sport horse world almost exclusively for endurance competitions. Breeders continue to use Arabian sires with Thoroughbred dams to enhance the sensitivity of the offspring for use in equestrian sports. This Arabian/Thoroughbred cross is known as an Anglo-Arabian.

True hot bloods usually offer both greater riding challenges and rewards than other horses. Their sensitivity and intelligence enable quick learning with greater communication and cooperation with their riders. However, their intelligence also allows them to learn bad habits as quickly as good ones. Because of this, they also can quickly lose trust in a poor rider and do not tolerate inept or abusive training practices.

Cold bloods Muscular and heavy draft horses are known as "cold bloods", as they have been bred to have the calm, steady, patient temperament needed to pull a plow or a heavy carriage full of people. One of the most best-known draft breeds is the Belgian. The largest is the Shire. The Clydesdales, with their common coloration of a bay or black coat with white legs and long-haired, "feathered" fetlocks are among the most easily recognized. [5]

Warmbloods "Warmblood" breeds began when the European carriage and war horses were crossed with Arabians, Anglo-Arabians and Thoroughbreds. The term "warm blood" was originally used to mean any cross of heavy horses on Thoroughbred or Arabian horses. Examples included breeds such as the Irish Draught horse, and sometimes also referred to the "Baroque" horses used for "high school" dressage, such as the Lipizzaner, Andalusian, Lusitano and the Alter Real. Sometimes the term was even used to refer to breeds of light riding horse other than Thoroughbreds or Arabians, such as the Morgan horse. But today the term "warmblood" usually refers to a group of sport horse breeds that have dominated the Olympic Games and World Equestrian Games in Dressage and Show Jumping since the 1950s. These breeds include the Hanoverian, Oldenburg, Trakehner, Holsteiner, Swedish Warmblood, and Dutch Warmblood.

The list of horse breeds provides a partial alphabetical list of breeds of horse extant today, plus a discussion of rare breeds' conservation.

Miscellaneous

Saddling and mounting

The common European practice and tradition of saddling and mounting the horse from the left hand side is sometimes said to originate from the practice of right-handed fighters carrying their sheathed sword on their left hip, making it easier to throw their right leg over the horse when mounting, and sometimes it is regarded as a superstition. However, several other explanations are equally plausible.

Horses can be mounted bareback with a vault from the ground, by grabbing the mane to provide leverage as a rider makes a small jump and scrambles up onto the horse's back (an awkward but popular method used by children), or by "bellying over", a technique which involves placing both hands side by side on the horse's back, jumping up so that the rider lays belly down on the horse's back, and swinging the leg over to sit astride. Some people prefer to bareback pads, which are basically sheepskin cushions, when riding bareback, especially on old, under-nurished or bony horses.

In actual practice, however, most bareback riders use a fence or mounting block, or another objet which can be stood upon to be able to simply slide onto the horse's back. This method is more convenient for both horse and rider, as the horse does not like someone "hiking' onto their back, and the "hiking" can be found to be very difficult for the rider, especially if the horse is tall or large.

Zodiac

The horse features in the 12-year cycle of animals which appear in the Chinese zodiac related to the Chinese calendar. According to Chinese folklore, each animal is associated with certain personality traits, and those born in the year of the horse are: intelligent, independent and free-spirited. See: Horse (Zodiac).

References

- ↑ Budiansky, Stephen. The Nature of Horses. Free Press, 1997. ISBN 0-684-82768-9

- ↑ Bennett, Deb. Conquerors: The Roots of New World Horsemanship. Amigo Publications Inc; 1st edition 1998. ISBN 0-9658533-0-6

- ↑ http://www.treemail.nl/takh/

- ↑ http://www.imh.org/imh/bw/tbred.html#hist

- ↑ http://images.google.com/images?&q=budweiser+clydesdale&btnG=Search

Bibliography

- Book of Horses: A Complete Medical Reference Guide for Horses and Foals, edited by Mordecai Siegal. (By members of the faculty and staff, University of California, Davis, School of Veterinary Medicine.) Harper Collins, 1996.

- Illustrated Atlas of Clinical Equine Anatomy and Common Disorders of the Horse, by Ronald J. Riegal, D.V.M. and Susan E. Hakola, B.S., R.N., C.M.I. Equistar Publications, Ltd., 1996.

- International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature. 2003. Opinion 2027 (Case 3010). Usage of 17 specific names based on wild species which are pre-dated by or contemporary with those based on domestic animals (Lepidoptera, Osteichthyes, Mammalia): conserved. Bull.Zool.Nomencl., 60:81-84.

- Bennett, Deb. Conquerors: The Roots of New World Horsemanship. Amigo Publications Inc; 1st edition 1998. ISBN 0-9658533-0-6

- Budiansky, Stephen. The Nature of Horses. Free Press, 1997. ISBN 0-684-82768-9

See also

- List of equine topics

- Classic equitation books

- List of fictional horses

- List of historical horses

- List of horse accidents

External links

Template:Commonscat Template:Wikispecies

- Horse breeds database. Oklahoma State University. Retrieved on 2006-09-14.

ang:Hors ar:حصان ast:Caballu bo:རྟ་ bg:Кон ca:Cavall cs:Kůň cy:Ceffyl da:Hest pdc:Gaul de:Hauspferd et:Hobune el:Άλογο es:Caballo eo:Ĉevalo fa:اسب fr:Cheval gl:Cabalo ko:말 (동물) io:Kavalo id:Kuda ia:Cavallo os:Бæх is:Hestur it:Equus caballus he:סוס ka:ცხენი kw:Margh ku:Hesp la:Equus lv:zirgs lt:Arklys li:Taam peêrd hu:Ló nah:Cahuāyoh nl:Paard (dier) ja:ウマ no:Hest nrm:J'va ug:ئوينىماق nds:Peerd pl:Koń pt:Cavalo ro:Cal ru:Лошадь sl:Konj sr:Коњ fi:Hevonen sv:Häst th:ม้า tg:Асп tr:At zh:马