Karl Marx: Difference between revisions

imported>Domergue Sumien (copyedit) |

Pat Palmer (talk | contribs) m (Text replacement - "Joseph Stalin|Stalin" to "Stalin") |

||

| (83 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

{{TOC|left}} | |||

{{Image|Karl Marx.jpg|right|200px|Karl Marx.}} | {{Image|Karl Marx.jpg|right|200px|Karl Marx.}} | ||

'''Karl Marx''' | '''Karl Marx''' (1818-1883) is generally thought of as the co-founder, with [[Friedrich Engels]], of the political movement known as [[communism]]. He made historically significant contributions to the intellectual disciplines of [[philosophy]], [[economics]], [[politics]] and [[historicism]]. Of his many written contributions to those disciplines, the best-known is the three-volume "Das Kapital", and he was co-author, with Engels, of the [[/Addendum#Communist Manifesto|Communist Manifesto]]. Their slogan "workers of the world unite" became the rallying calls for revolutionary movements including Russia's [[Russian Revolution|Bolshevik Revolution of 1917]] and the [[Chinese Revolution (1949)|Chinese Revolution of 1949]]; and Marx's advocacy of "from each according to his ability, to each according to his need" has been the inspiration of communist parties throughout the world. | ||

== | ==Overview== | ||

Karl | Karl Marx underwent a transition from academic theoretician to political activist - leaving an influential legacy in both fields. As a | ||

student of philosophy he accepted the tenets of traditional [[humanism]], but he later developed his own interpretation in which religion is a response to hardship, and one that is destined to survive until its cause is removed. He sought an explanation for working class hardships in the theories of [[History of economic thought#Classical Economics|classical economics]] and developed his own analysis which concluded that [[capitalism]] deprives working people of all of the fruits of their [[labour]] beyond the amounts necessary for their subsistence. His analysis of historicism led him to the conclusion that capitalism contained the seeds of its own destruction, and that its overthrow would happen first where the development of capitalism was most advanced. His political theories were concerned with the processes by which capitalism could be replaced by a system governed by the principle of "from each according to his ability, to each according to his need". As a political activist, he played a major part in the promotion of [[communism]], and was a founder member of the [[Communist League]] (later to become the [[Communist International]]). His intellectual legacy was globally influential despite the development of a consensus among academic economists that his economic analysis was flawed. His political proposals were taken up and developed by [[Lenin]] and others, and were the inspiration of Russia's [[Bolshevism|Bolshevik]] Revolution and of communist revolutions in China, Cuba and elsewhere. | |||

== | ==Life and works== | ||

In 1836 Marx transferred to the University of Berlin | :''(Additional links are available in the detailed chronology on the [[/Timelines|timelines subpage]])''<br> | ||

Karl Heinrich Marx was born into a middle-class home in the Rhineland city of Trier, in Germany. He came, on both sides of his family, from a long line of Jewish rabbis, but his family converted to Lutheranism in 1824. Marx received a classical education and at the age of 17 he spent a year in the University of Bonn's law faculty. At age 18 he became engaged to Jenny von Westphalen (1814-1881), daughter of Baron von Westphalen, a prominent member of Trier society. In 1836 Marx transferred to the University of Berlin and came under the influence of the philosophy of G.W.F Hegel which then dominated the movement known as [[The German Ideology|German Idealism]]. After completing his doctoral thesis (which dealt with the atomic theories of Democritus and Epicurus), he turned to journalism and began writing for the ''Rheinische Zeitung,'' an opposition daily backed by liberal Rhenish industrialists. He soon became its editor, but the paper was closed by the authorities in May 1843 and he moved to Paris. Married to Jenny von Westphalen, he recorded his departure from Hegel's thesis in his "Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right", in which he refers to religion as "the opium of the people". In Paris he developed what was to be a life-long association with Friedrich Engels, and set out his thoughts about communism in what are now known as "the Paris manuscripts". Expelled from France, he moved to Brussels and recorded his developing philosophical thoughts in his "Theses on Feuerbach". Expelled from France he moved to Brussels and recorded his developing philosophical views in his "Theses on Feuerbach". In 1846 Marx wrote [[The German Ideology]] with Engels, a text which lays the foundation for [[/Addendum#The Communist Manifesto|The Communist Manifesto]]. Returning to France on the news of the (unsuccessful) revolution of 1848, he began work on a series of pamphlets on "the class struggles in France" and in 1848, he and Friedrich Engels published the "Communist Manifesto". After moving to London in 1849 he devoted years of endeavour to his major work: "Das Kapital". Throughout the latter years of his life until his death in 1883, he was an active supporter of the Communist League, that was later to become the Communist International. | |||

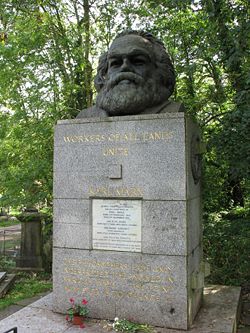

[[ | [[Image:Karl Marx grave.jpg|right|thumb|250px|{{#ifexist:Template:Karl Marx grave.jpg/credit|{{Karl Marx grave.jpg/credit}}<br/>|}}Grave of Karl Marx in Highgate Cemetery, [[London, United Kingdom|London]]]] | ||

== Theoretical contributions== | |||

:''(Links to Marx's major works are available on the [[/Works|Works subpage]])'' | |||

=== Philosophy=== | |||

Marx was influenced by the German ideology of the 18th century and early 19th centuries, and in particular by Ludwig Feuerbach's | |||

<ref>[http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ludwig-feuerbach/ ''Ludwig Andreas Feuerbach'' Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, July 2007]</ref> humanist contention that man has invented God in his own image<ref> Ludwig Feuerbach: ''The Essence of Christianity'', (1854) Prometheus Books, 1989</ref>. He accepted that man had invented God, but argued he had done so in order to deaden the pain of the poverty-stricken misery of life on earth<ref>[http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1843/critique-hpr/index.htm Karl Marx: ''Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right'' (ebook)]</ref>. He was not content with a philosophy that deals only in beliefs and ideals, arguing that it should seek a reasoned explanation of the physical interactions between man and his environment. He considered existing explanations to be inadequate, and his own search for an explanation led him to adapt the teachings of the [[History of economic thought#Classical economics|classical economists]] and to develop the historicist teachings of the [[The German Ideology|German ideologists]]. He became convinced that intolerable hardship is an inherent characteristic of [[capitalism]] and that it could be overcome only by its replacement by the version of [[communism]] that he and Friedrich Engels set out in the [[/Addendum#Communist Manifesto|Communist Manifesto]]. He also became convinced that the historical development of capitalism would lead ultimately to its collapse, and that the [[state]] would then be replaced by an undefined form of social [[governance]] that he termed "the dictatorship of the proletariat". The hastening of that outcome became his main objective and he turned away from philosophy on the grounds that, as he put it, "philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.''<ref>[http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/theses/index.htm Karl Marx: ''Theses On Feuerbach'', paragraph 11, (1845) (ebook)]</ref>. | |||

=== | === Economics=== | ||

Karl Marx used the classical economics concepts of [[use value]] and [[exchange value]] to construct a labour theory of value in which the exchange value of a commodity is determined by the time required for its production<ref>He actually said it was the "socially necessary time", by which he meant the time taken by a typical worker</ref>. His theory treats labour as a commodity whose exchange value (or cost to the capitalist employer) to be the value of the goods necessary for its supplier's subsistence, and takes the use value of of labour (to its employer) to be the value of what its supplier produces. The capitalist employer's profit is taken to be the excess of the use value of labour over its exchange value: an excess which is termed "surplus value". Using those propositions as axioms, Marx made extensive use of logical [[deduction]] to construct a comprehensive theory of the economics of capitalism, which he published as "Das Kapital"<ref name=Kapital>Karl Marx ''Capital''. (First published: in German in 1867 ( [http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/pdf/Capital-Volume-I.pdf ebook vol 1][http://extratorrent.com/torrent/1661590/Ebook+-+The+Capital+by+Karl+Marx+-+Volume+2.html vol 2][http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/pdf/Capital-Volume-III.pdf vol 3])</ref>. | |||

[[ | In it, unemployment is explained as the result of the introduction by employers of labour-saving machinery in response to an initial rise in the cost of labour, and it is argued that the resulting creation of a "reserve army of the unemployed" serves to stifle any continuing tendency for wages to rise. It attributes economic growth mainly to technical progress, and there is a systematic attempt to explain fluctuations in economic activity in terms of capitalism's need to maintain that growth. (It is argued that whenever technical progress slows down, the fall in growth leads to an accumulation of unwanted stocks of goods, producing a downturn in economic activity - until price-cutting, in order to get rid of surpluses, put the process into reverse.) It also predicts the ultimate demise of capitalism on the grounds that competition among capitalists will force them to accumulate more and more capital, and in so doing, to drive down the rate of profit. | ||

=== Historicism=== | |||

As Marx (and Engels) saw it, "the history of all hitherto existing society is a history of class struggle<ref>[http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/61Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels: ''The Communist Manifesto'' (ebook)]</ref>. Marx argued that social systems change with the conditions of production because those conditions determine the way that the ruling [[Social class|classes]] can exploit the ruled. Thus, for every period of economic development, there is a corresponding class system. "The handmill gives you a society with the feudal lord; the steam-mill gives you a society with the industrial [[capitalism|capitalist]] <ref>[http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1847/poverty-philosophy/index.htm ''The Poverty of Philosophy'' (ebook)]</ref>. Marx surmised that each system must have contained forces that led to its demise and replacement by a successor, and he was convinced that such was true of capitalism. He believed that, as a capitalist system approached maturity, power would become more and more concentrated and the sufferings of the [[proletariat]] more and more intense; and that the resulting social stresses would lead to [[revolution]]. He took it for granted that such a revolution would lead to the creation of a classless, "[[socialism|socialist]]" society: | |||

:"In history up to the present it is certainly an empirical fact that individuals have ... become more and more enslaved under a power alien to them ... But it is just as empirically established that, by the overthrow of the existing state of society by the communist revolution .... and the abolition of private property which is identical with it, this power ... will be dissolved; and that then the liberation of each single individual will be accomplished.".<ref>[http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/german-ideology/ Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels: ''The German Ideology'' 1846 (ebook)]</ref>. | |||

=== Politics=== | |||

Because Marx was convinced that peoples' actions are governed by the social system, and not the other way round, he did not believe that the capitalist system could be changed by political action. The proletariat could not be freed from oppression by democratic action, but only by revolution: | |||

:"Between capitalist and communist society there lies the period of the revolutionary transformation of the one into the other. Corresponding to this is also a political transition period in which the state can be nothing but the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat"<ref>[[http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1875/gotha/ Karl Marx: ''Critique of the Gotha Programme'', 1875 (ebook)]</ref>. | |||

He explained the apparent inconsistency between those statements and his own rôle as a political activist in a statement in ''Das Kapital'': | |||

: "(Society) can neither clear by bold leaps, nor remove by legal enactments, the obstacles offered by the successive phases of its normal development. But it can shorten and lessen the birth-pangs"<ref>[http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/p1.htm Karl Marx ''Capital'', Volume One, Preface to the First German Edition (ebook)]</ref> | |||

At no point did either Marx or Engels discuss the means by which people would contribute "each according to his ability" and receive "each according to his needs". Engels' much-quoted forecast of the "withering away" of the state was later qualified in correspondence: | |||

: "Marx and I, ever since 1845, have held the view that one of the final results of the future proletarian revolution will be the gradual dissolution and ultimate disappearance of that political organisation called the State; an organisation the main object of which has been to secure, by armed force, the economical subjection of the working majority to the wealthy minority. At the same time we have always held that in order to arrive at this and the other, far more important ends of the social revolution of the future, the proletarian class will first have to possess itself of the organised political force of the state and with this aid stamp out the resistance of the capitalist class and re-organise society"<ref>[http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1883/letters/83_04_18.htm Friedrich Engels in a letter to Philip van Patten, April 18, 1883]</ref>. | |||

Nothing is available, however, concerning the characteristics of the reorganisation that they envisaged. | |||

== Legacy== | |||

:''(links to the writings of supporters, reviewers and critics are available on the [[/Bibliography|bibliography subpage]])'' | |||

=== Intellectual impact=== | |||

Before the First World War, Marx's writings aroused few favourable responses outside Eastern Europe. Their enthusiastic promotion by Lenin was clearly a major influence upon the Russian revolutions, and their (partial) adoption as the official ideology of the Soviet Union was followed by a surge of post-war influence. In the 1920s, the Frankfurt Group of intellectuals <ref>[http://www.marxists.org/subject/frankfurt-school/ ''The Frankfurt School of German Intellectual and “Critical Theory”'', www.marxists.org]</ref> met to debate and disseminate Marxism, and they were later joined by the American philosopher Herbert Marcuse. | |||

According to the Marxist historian, Eric Hobsbawm<ref>[http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2002/sep/14/biography.history Maya Jaggi ''A question of faith'', The Guardian, 14 September 2002]</ref>, Marxism became a serious force among intellectuals of Western Europe and the English-speaking world in the 1930s and its intellectual influence reached a peak in the 1970s, but has since declined | |||

<ref name=hob>Eric Hobsbawm: "How to Change the World'', Little Brown, 2011.</ref>. Marx's surviving intellectual legacy has - with minor exceptions - been confined to the discipline of philosophy. His contribution to historicism has been largely discredited as the result of the evident failure of its predictions, and his labour theory of value has not gained acceptance by academic economists. (The originality of some of his economic insights commands respect, however<ref>[http://s3.amazonaws.com/files.posterous.com/braddelong/Nz8hlhxt0Kz8z5aCtmg03Dd8XbowaRN2gYXGXBTE7tmnl41ao99oOjVk6ldd/20090420_Stanford_Marx.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAJFZAE65UYRT34AOQ&Expires=1333657893&Signature=KAYaYm2OPaLwX8uyBBDPk7t4pCs%3D J. Bradford DeLong: ''Understanding Karl Marx'', April 20, 2009]</ref>, and he is believed to be the first economist to make a study of the trade cycle<ref>[http://www.aracneeditrice.it/pdf/2780.pdf Claude Diebolt: ''Business Cycle Theory before Keynes'', ARACNE, 2009]</ref>.) | |||

=== | === Political impact=== | ||

Marx's political legacy has been immense. Hobsbawm has noted that Marxism became the official ideology of states in which, at their peak, something like a third of the human race lived<ref name=hob/>. His teachings have also influenced the emergence of [[Socialism|socialist]] and [[Social democracy|social democratic]] movements that did not adopt Marxism as their ideology, or have since abandoned it. Their immediate impact was on the [[Communism|communist]] movement, which he and Friedrich Engels invigorated by welding together a disparate collection of local organisations, and providing them with a coherent rationale and an explicit set of objectives. His longer-term impact was increased by the interest taken in his writings by the politically active [[Lenin]], who was 52 years his junior and by the endorsement of Marxism by [[[[Joseph Stalin|Stalin]]]]<ref> [http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/stalin/works/1938/09.htm Joseph Stalin, ''Dialectical and Historical Materialism'', (1938) (ebook)]</ref> and [[Mao Zedong]]<ref>[http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/selected-works/volume-1/mswv1_17.htm Mao Tse-tung, ''On Contradiction'' (ebook)]</ref>. Some of his writings - and in particular the Communist Manifesto - are familiar to millions of political activists throughout the world, and they have also been a major factor in the adoption of forms of communism by the Soviet Union, and subsequently by the governments of North Korea, China, Nepal, Albania, Cuba, Venezuela, Bolivia, Nicaragua and others. | |||

==Footnotes and references== | |||

{{reflist}}[[Category:Suggestion Bot Tag]] | |||

== | |||

Latest revision as of 11:43, 1 October 2024

Karl Marx (1818-1883) is generally thought of as the co-founder, with Friedrich Engels, of the political movement known as communism. He made historically significant contributions to the intellectual disciplines of philosophy, economics, politics and historicism. Of his many written contributions to those disciplines, the best-known is the three-volume "Das Kapital", and he was co-author, with Engels, of the Communist Manifesto. Their slogan "workers of the world unite" became the rallying calls for revolutionary movements including Russia's Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and the Chinese Revolution of 1949; and Marx's advocacy of "from each according to his ability, to each according to his need" has been the inspiration of communist parties throughout the world.

Overview

Karl Marx underwent a transition from academic theoretician to political activist - leaving an influential legacy in both fields. As a student of philosophy he accepted the tenets of traditional humanism, but he later developed his own interpretation in which religion is a response to hardship, and one that is destined to survive until its cause is removed. He sought an explanation for working class hardships in the theories of classical economics and developed his own analysis which concluded that capitalism deprives working people of all of the fruits of their labour beyond the amounts necessary for their subsistence. His analysis of historicism led him to the conclusion that capitalism contained the seeds of its own destruction, and that its overthrow would happen first where the development of capitalism was most advanced. His political theories were concerned with the processes by which capitalism could be replaced by a system governed by the principle of "from each according to his ability, to each according to his need". As a political activist, he played a major part in the promotion of communism, and was a founder member of the Communist League (later to become the Communist International). His intellectual legacy was globally influential despite the development of a consensus among academic economists that his economic analysis was flawed. His political proposals were taken up and developed by Lenin and others, and were the inspiration of Russia's Bolshevik Revolution and of communist revolutions in China, Cuba and elsewhere.

Life and works

- (Additional links are available in the detailed chronology on the timelines subpage)

Karl Heinrich Marx was born into a middle-class home in the Rhineland city of Trier, in Germany. He came, on both sides of his family, from a long line of Jewish rabbis, but his family converted to Lutheranism in 1824. Marx received a classical education and at the age of 17 he spent a year in the University of Bonn's law faculty. At age 18 he became engaged to Jenny von Westphalen (1814-1881), daughter of Baron von Westphalen, a prominent member of Trier society. In 1836 Marx transferred to the University of Berlin and came under the influence of the philosophy of G.W.F Hegel which then dominated the movement known as German Idealism. After completing his doctoral thesis (which dealt with the atomic theories of Democritus and Epicurus), he turned to journalism and began writing for the Rheinische Zeitung, an opposition daily backed by liberal Rhenish industrialists. He soon became its editor, but the paper was closed by the authorities in May 1843 and he moved to Paris. Married to Jenny von Westphalen, he recorded his departure from Hegel's thesis in his "Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right", in which he refers to religion as "the opium of the people". In Paris he developed what was to be a life-long association with Friedrich Engels, and set out his thoughts about communism in what are now known as "the Paris manuscripts". Expelled from France, he moved to Brussels and recorded his developing philosophical thoughts in his "Theses on Feuerbach". Expelled from France he moved to Brussels and recorded his developing philosophical views in his "Theses on Feuerbach". In 1846 Marx wrote The German Ideology with Engels, a text which lays the foundation for The Communist Manifesto. Returning to France on the news of the (unsuccessful) revolution of 1848, he began work on a series of pamphlets on "the class struggles in France" and in 1848, he and Friedrich Engels published the "Communist Manifesto". After moving to London in 1849 he devoted years of endeavour to his major work: "Das Kapital". Throughout the latter years of his life until his death in 1883, he was an active supporter of the Communist League, that was later to become the Communist International.

Theoretical contributions

- (Links to Marx's major works are available on the Works subpage)

Philosophy

Marx was influenced by the German ideology of the 18th century and early 19th centuries, and in particular by Ludwig Feuerbach's [1] humanist contention that man has invented God in his own image[2]. He accepted that man had invented God, but argued he had done so in order to deaden the pain of the poverty-stricken misery of life on earth[3]. He was not content with a philosophy that deals only in beliefs and ideals, arguing that it should seek a reasoned explanation of the physical interactions between man and his environment. He considered existing explanations to be inadequate, and his own search for an explanation led him to adapt the teachings of the classical economists and to develop the historicist teachings of the German ideologists. He became convinced that intolerable hardship is an inherent characteristic of capitalism and that it could be overcome only by its replacement by the version of communism that he and Friedrich Engels set out in the Communist Manifesto. He also became convinced that the historical development of capitalism would lead ultimately to its collapse, and that the state would then be replaced by an undefined form of social governance that he termed "the dictatorship of the proletariat". The hastening of that outcome became his main objective and he turned away from philosophy on the grounds that, as he put it, "philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.[4].

Economics

Karl Marx used the classical economics concepts of use value and exchange value to construct a labour theory of value in which the exchange value of a commodity is determined by the time required for its production[5]. His theory treats labour as a commodity whose exchange value (or cost to the capitalist employer) to be the value of the goods necessary for its supplier's subsistence, and takes the use value of of labour (to its employer) to be the value of what its supplier produces. The capitalist employer's profit is taken to be the excess of the use value of labour over its exchange value: an excess which is termed "surplus value". Using those propositions as axioms, Marx made extensive use of logical deduction to construct a comprehensive theory of the economics of capitalism, which he published as "Das Kapital"[6]. In it, unemployment is explained as the result of the introduction by employers of labour-saving machinery in response to an initial rise in the cost of labour, and it is argued that the resulting creation of a "reserve army of the unemployed" serves to stifle any continuing tendency for wages to rise. It attributes economic growth mainly to technical progress, and there is a systematic attempt to explain fluctuations in economic activity in terms of capitalism's need to maintain that growth. (It is argued that whenever technical progress slows down, the fall in growth leads to an accumulation of unwanted stocks of goods, producing a downturn in economic activity - until price-cutting, in order to get rid of surpluses, put the process into reverse.) It also predicts the ultimate demise of capitalism on the grounds that competition among capitalists will force them to accumulate more and more capital, and in so doing, to drive down the rate of profit.

Historicism

As Marx (and Engels) saw it, "the history of all hitherto existing society is a history of class struggle[7]. Marx argued that social systems change with the conditions of production because those conditions determine the way that the ruling classes can exploit the ruled. Thus, for every period of economic development, there is a corresponding class system. "The handmill gives you a society with the feudal lord; the steam-mill gives you a society with the industrial capitalist [8]. Marx surmised that each system must have contained forces that led to its demise and replacement by a successor, and he was convinced that such was true of capitalism. He believed that, as a capitalist system approached maturity, power would become more and more concentrated and the sufferings of the proletariat more and more intense; and that the resulting social stresses would lead to revolution. He took it for granted that such a revolution would lead to the creation of a classless, "socialist" society:

- "In history up to the present it is certainly an empirical fact that individuals have ... become more and more enslaved under a power alien to them ... But it is just as empirically established that, by the overthrow of the existing state of society by the communist revolution .... and the abolition of private property which is identical with it, this power ... will be dissolved; and that then the liberation of each single individual will be accomplished.".[9].

Politics

Because Marx was convinced that peoples' actions are governed by the social system, and not the other way round, he did not believe that the capitalist system could be changed by political action. The proletariat could not be freed from oppression by democratic action, but only by revolution:

- "Between capitalist and communist society there lies the period of the revolutionary transformation of the one into the other. Corresponding to this is also a political transition period in which the state can be nothing but the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat"[10].

He explained the apparent inconsistency between those statements and his own rôle as a political activist in a statement in Das Kapital:

- "(Society) can neither clear by bold leaps, nor remove by legal enactments, the obstacles offered by the successive phases of its normal development. But it can shorten and lessen the birth-pangs"[11]

At no point did either Marx or Engels discuss the means by which people would contribute "each according to his ability" and receive "each according to his needs". Engels' much-quoted forecast of the "withering away" of the state was later qualified in correspondence:

- "Marx and I, ever since 1845, have held the view that one of the final results of the future proletarian revolution will be the gradual dissolution and ultimate disappearance of that political organisation called the State; an organisation the main object of which has been to secure, by armed force, the economical subjection of the working majority to the wealthy minority. At the same time we have always held that in order to arrive at this and the other, far more important ends of the social revolution of the future, the proletarian class will first have to possess itself of the organised political force of the state and with this aid stamp out the resistance of the capitalist class and re-organise society"[12].

Nothing is available, however, concerning the characteristics of the reorganisation that they envisaged.

Legacy

- (links to the writings of supporters, reviewers and critics are available on the bibliography subpage)

Intellectual impact

Before the First World War, Marx's writings aroused few favourable responses outside Eastern Europe. Their enthusiastic promotion by Lenin was clearly a major influence upon the Russian revolutions, and their (partial) adoption as the official ideology of the Soviet Union was followed by a surge of post-war influence. In the 1920s, the Frankfurt Group of intellectuals [13] met to debate and disseminate Marxism, and they were later joined by the American philosopher Herbert Marcuse. According to the Marxist historian, Eric Hobsbawm[14], Marxism became a serious force among intellectuals of Western Europe and the English-speaking world in the 1930s and its intellectual influence reached a peak in the 1970s, but has since declined [15]. Marx's surviving intellectual legacy has - with minor exceptions - been confined to the discipline of philosophy. His contribution to historicism has been largely discredited as the result of the evident failure of its predictions, and his labour theory of value has not gained acceptance by academic economists. (The originality of some of his economic insights commands respect, however[16], and he is believed to be the first economist to make a study of the trade cycle[17].)

Political impact

Marx's political legacy has been immense. Hobsbawm has noted that Marxism became the official ideology of states in which, at their peak, something like a third of the human race lived[15]. His teachings have also influenced the emergence of socialist and social democratic movements that did not adopt Marxism as their ideology, or have since abandoned it. Their immediate impact was on the communist movement, which he and Friedrich Engels invigorated by welding together a disparate collection of local organisations, and providing them with a coherent rationale and an explicit set of objectives. His longer-term impact was increased by the interest taken in his writings by the politically active Lenin, who was 52 years his junior and by the endorsement of Marxism by [[Stalin]][18] and Mao Zedong[19]. Some of his writings - and in particular the Communist Manifesto - are familiar to millions of political activists throughout the world, and they have also been a major factor in the adoption of forms of communism by the Soviet Union, and subsequently by the governments of North Korea, China, Nepal, Albania, Cuba, Venezuela, Bolivia, Nicaragua and others.

Footnotes and references

- ↑ Ludwig Andreas Feuerbach Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, July 2007

- ↑ Ludwig Feuerbach: The Essence of Christianity, (1854) Prometheus Books, 1989

- ↑ Karl Marx: Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right (ebook)

- ↑ Karl Marx: Theses On Feuerbach, paragraph 11, (1845) (ebook)

- ↑ He actually said it was the "socially necessary time", by which he meant the time taken by a typical worker

- ↑ Karl Marx Capital. (First published: in German in 1867 ( ebook vol 1vol 2vol 3)

- ↑ Marx and Friedrich Engels: The Communist Manifesto (ebook)

- ↑ The Poverty of Philosophy (ebook)

- ↑ Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels: The German Ideology 1846 (ebook)

- ↑ [Karl Marx: Critique of the Gotha Programme, 1875 (ebook)

- ↑ Karl Marx Capital, Volume One, Preface to the First German Edition (ebook)

- ↑ Friedrich Engels in a letter to Philip van Patten, April 18, 1883

- ↑ The Frankfurt School of German Intellectual and “Critical Theory”, www.marxists.org

- ↑ Maya Jaggi A question of faith, The Guardian, 14 September 2002

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Eric Hobsbawm: "How to Change the World, Little Brown, 2011.

- ↑ J. Bradford DeLong: Understanding Karl Marx, April 20, 2009

- ↑ Claude Diebolt: Business Cycle Theory before Keynes, ARACNE, 2009

- ↑ Joseph Stalin, Dialectical and Historical Materialism, (1938) (ebook)

- ↑ Mao Tse-tung, On Contradiction (ebook)