Intelligence on the Korean War: Difference between revisions

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz (Reviewed Rose cites, and I believe every one refers to specific CIA reporting, not journalistic accounts. There is good and bad in his article.) |

Pat Palmer (talk | contribs) m (Text replacement - "guided missile" to "guided missile") |

||

| (15 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

When the [[Democratic People's | {{TOC|right}} | ||

When the army of the [[Democratic People's Republic of Korea]] (DPRK, "North Korean" army. also NKPA) attacked the [[Republic of Korea]] (ROK, "South Korea") on June 15, 1950, it was a surprise to the United States and the Republic of Korea. In the case of the United States, the failure to anticipate may well have been the lack of senior government priority on the Korean Peninsula, and the still confused post-World War II U.S. intelligence structure. It is less clear why South Korea also was surprised at the highest levels. Still, the warnings were from relatively low-ranking levels and not definitive. | |||

It is less clear why South Korea also was surprised at the highest levels. Still, the warnings were from relatively low-ranking levels and not definitive. | |||

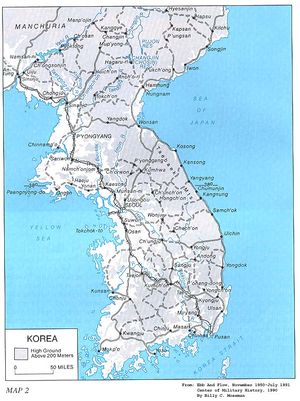

[[Image:BaseMapOfKorea.jpg|left|thumb|Map of the divided Korea]] | [[Image:BaseMapOfKorea.jpg|left|thumb|Map of the divided Korea]] | ||

The last U.S. tactical units | The last U.S. tactical units had left South Korea in 1949, leaving only the Korea [[U.S. foreign military assistance organizations|Military Assistance Advisory Group]] (KMAG), which did not report to [[Douglas MacArthur]], commanding [[Far Eastern Armed Forces]]. MacArthur had his own intelligence organization, "G-2", under MG [[Charles Willoughby]], but FEAF G-2 did not have an explicit intelligence responsibility for Korea. The MAAG, reporting to the Pentagon, had the U.S. responsibility in the field. <ref name=Schnabel>{{citation | ||

| title = United States Army in the Korean War, Policy and Direction: the First Year | | title = United States Army in the Korean War, Policy and Direction: the First Year | ||

| first = James F. | last = Schnabel | | first = James F. | last = Schnabel | ||

| publisher = Center for Military History, U.S. Department of the Army | | publisher = Center for Military History, U.S. Department of the Army | ||

| date = 1972 | | date = 1972 | ||

| url = http://www.history.army.mil/books/P&D.HTM}}</ref> | | url = http://www.history.army.mil/books/P&D.HTM}}</ref> | ||

By 1949, the U.S. had concluded that withdrawing its occupation troops would probably lead to an invasion, but the [[Joint Chiefs of Staff]] did not want to fight in Korea, believing that the conditions would be too favorable to the other side. Essentially, Korea had been written off. | By 1949, the U.S. had concluded that withdrawing its occupation troops would probably lead to an invasion, but the [[Joint Chiefs of Staff]] did not want to fight in Korea, believing that the conditions would be too favorable to the other side. Essentially, Korea had been written off. | ||

In mid-1949, however, [[ | In mid-1949, however, [[Chief of Staff of the Army]] [[Omar Bradley]] had his staff develop a plan to bring the matter before the [[United Nations]] should there be an invasion, and, if diplomacy failed, form a UN multinational military force. | ||

==Failure to anticipate== | ==Failure to anticipate== | ||

Failure to anticipate the attack on the South was, in part, a result of the combined cutbacks in military and intelligence budgets after World War II, and the [[containment strategy]] against the Soviet bloc, which was principally focused on the Soviet Union itself, on China to a lesser extent, and essentially ignoring small bloc states such as North Korea. Schnabel suggests that this was only logical after the U.S. had written off Korea as strategically significant. | Failure to anticipate the attack on the South was, in part, a result of the combined cutbacks in military and intelligence budgets after World War II, and the [[containment strategy]] against the Soviet bloc, which was principally focused on the Soviet Union itself, on China to a lesser extent, and essentially ignoring small bloc states such as North Korea. Schnabel suggests that this was only logical after the U.S. had written off Korea as strategically significant. | ||

There was U.S. intelligence activity by the U.S. [[Korea Military Assistance Group]] (KMAG), who worked with ROK counterparts to analyze intelligence on North Korea. KMAG reported to Washington, not MacArthur. <ref name=Schnabel /> It had the intelligence responsibility, sent reports to Washington, which sent it, along with CIA and other reports, to MacArthur. They sent this information to Washington periodically and on occasion made special reports. Other agencies and units in the Far East reported to appropriate officials in Washington. [[ | There was U.S. intelligence activity by the U.S. [[Korea Military Assistance Group]] (KMAG), who worked with ROK counterparts to analyze intelligence on North Korea. KMAG reported to Washington, not MacArthur. <ref name=Schnabel /> It had the intelligence responsibility, sent reports to Washington, which sent it, along with CIA and other reports, to MacArthur. They sent this information to Washington periodically and on occasion made special reports. Other agencies and units in the Far East reported to appropriate officials in Washington. [[Signals intelligence at the start of the Cold War#Pacific COMINT targeting prior to the Korean War|Communications intelligence]] monitored North Korean communications only to the extent that they provided information on Soviet activities. | ||

An additional problem was that [[Douglas MacArthur]] wanted intelligence under his direct control. During the Second World War, he had not allowed the predecessor of the [[Central Intelligence Agency]], the | An additional problem was that [[Douglas MacArthur]] wanted intelligence under his direct control. During the Second World War, he had not allowed the predecessor of the [[Central Intelligence Agency]], the Office of Strategic Services, to operate in his theater. U.S. intelligence, especially [[clandestine human-source intelligence]], was in a bureaucratic limbo between 1945 and 1952, when the CIA obtained firm control of clandestine human-source intelligence and covert action. | ||

Instead, he kept his own intelligence organization under his trusted intelligence officer, MG [[Charles Willoughby]]. In early 1950, General [[J. Lawton Collins]] asked MacArthur if he could provide information on areas outside his responsibility. MacArthur was reluctant to commit to regular reporting without orders to do so, but he thought he had the personnel to do so. <ref name=Schnabel /> | Instead, he kept his own intelligence organization under his trusted intelligence officer, MG [[Charles Willoughby]]. In early 1950, General [[J. Lawton Collins]] asked MacArthur if he could provide information on areas outside his responsibility. MacArthur was reluctant to commit to regular reporting without orders to do so, but he thought he had the personnel to do so. <ref name=Schnabel /> | ||

| Line 34: | Line 33: | ||

}}</ref> | }}</ref> | ||

"These reports establish the dominant theme in intelligence analysis from Washington that accounts for the failure to predict the North Korean attack—that the Soviets controlled North Korean | "These reports establish the dominant theme in intelligence analysis from Washington that accounts for the failure to predict the North Korean attack—that the Soviets controlled North Korean decision making. The Washington focus on the Soviet Union as “the” Communist state had become the accepted perception within US Government’s political and military leadership circles. Any scholarly counterbalances to this view, either questioning the absolute authority of Moscow over other Communist states or noting that cultural, historic, or nationalistic factors might come into play, fell victim to the political atmosphere." | ||

By April 1950, U.S. Army | By April 1950, U.S. Army communications intelligence made a limited "search and development" study of DPRK traffic. CIA received its reports. The COMINT revealed large shipments of bandages and medicines from the USSR to North Korea and Manchuria, starting in February 1950. These two actions made sense only in hindsight, after the invasion of South Korea occurred in June 1950. <ref name=NSA-Korea>{{citation | ||

| last =Hatch | | last =Hatch | ||

| first = David A. | | first = David A. | ||

| Line 50: | Line 49: | ||

In hindsight, there were warnings, in May-June 1950, of a potential attack in the near future. On 10 May, the South Korean Defense Ministry publicly warned at a press conference that DPRK troops were massing at the border and there was danger of an invasion...Throughout June, intelligence reports from South Korea and the CIA provide clear descriptions of DPRK preparations for war. These reports noted the removal of civilians from the border area, the restriction of all transport capabilities for military use only, and the movements of infantry and armor units to the border area. Also, following classic Communist political tactics, the DPRK began an international propaganda campaign against the ROK ''police state.'' <ref name=NSA-Korea /> | In hindsight, there were warnings, in May-June 1950, of a potential attack in the near future. On 10 May, the South Korean Defense Ministry publicly warned at a press conference that DPRK troops were massing at the border and there was danger of an invasion...Throughout June, intelligence reports from South Korea and the CIA provide clear descriptions of DPRK preparations for war. These reports noted the removal of civilians from the border area, the restriction of all transport capabilities for military use only, and the movements of infantry and armor units to the border area. Also, following classic Communist political tactics, the DPRK began an international propaganda campaign against the ROK ''police state.'' <ref name=NSA-Korea /> | ||

On 6 June, CIA informed U.S. policymakers that all East Asian senior Soviet diplomats were recalled to Moscow for consultations. Unfortunately, it was assumed this was to consult about a new plan to counter anti-Communist efforts in the region. On 20 June 1950, the CIA published a report, based primarily on HUMINT, concluding that the DPRK had the capability to invade the South at any time. President [[Harry S Truman]], [[United States Secretary of State]] [[Dean Acheson]], and [[United States Secretary of Defense]] [[Louis Johnson]] all received copies of this report. <ref name=Rose /> | On 6 June, CIA informed U.S. policymakers that all East Asian senior Soviet diplomats were recalled to Moscow for consultations. Unfortunately, it was assumed this was to consult about a new plan to counter anti-Communist efforts in the region. On 20 June 1950, the CIA published a report, based primarily on HUMINT, concluding that the DPRK had the capability to invade the South at any time. President [[Harry S. Truman]], [[United States Secretary of State]] [[Dean Acheson]], and [[United States Secretary of Defense]] [[Louis Johnson]] all received copies of this report. <ref name=Rose /> | ||

On June 25, 1950, [[Kim Il Sung]], the leader of Communist North Korea, sent troops of the [[North Korean People’s Army]] (NKPA) across the 38th parallel and invaded South Korea, heading toward its capital, [[Seoul]]. | On June 25, 1950, [[Kim Il Sung]], the leader of Communist North Korea, sent troops of the [[North Korean People’s Army]] (NKPA) across the 38th parallel and invaded South Korea, heading toward its capital, [[Seoul]]. | ||

| Line 64: | Line 63: | ||

A message ninety minutes later gave confirmation. General MacArthur immediately informed Washington and, within a few hours, sent the first comprehensive situation report on the Korean fighting."<ref name=Schnabel /> | A message ninety minutes later gave confirmation. General MacArthur immediately informed Washington and, within a few hours, sent the first comprehensive situation report on the Korean fighting."<ref name=Schnabel /> | ||

===Early intelligence analysis=== | ===Early intelligence analysis=== | ||

CIA intelligence reports, after the invasion, still treated North Korea as controlled by the USSR, but the reports did raise the possibility of Chinese involvement. On 26 June, CIA agreed with the US Embassy in Moscow that the North Korean offensive was a “... clear-cut Soviet challenge to the United States…” | CIA intelligence reports, after the invasion, still treated North Korea as controlled by the USSR, but the reports did raise the possibility of Chinese involvement. On 26 June, CIA agreed with the US Embassy in Moscow that the North Korean offensive was a “... clear-cut Soviet challenge to the United States…” | ||

| Line 72: | Line 72: | ||

On 30 June 1950, [as] President Truman authorized the use of US ground forces in Korea, CIA Intelligence Memorandum 301, Estimate of Soviet Intentions and Capabilities for Military Aggression, warned that the Soviets could commit large numbers of Chinese troops, which could be used in Korea to make US involvement costly and difficult. This warning was followed on 8 July by CIA Intelligence Memorandum 302, which stated that the Soviets were responsible for the invasion, and they could use Chinese forces to intervene if DPRK forces could not stand up to UN forces.<ref name=Rose /> | On 30 June 1950, [as] President Truman authorized the use of US ground forces in Korea, CIA Intelligence Memorandum 301, Estimate of Soviet Intentions and Capabilities for Military Aggression, warned that the Soviets could commit large numbers of Chinese troops, which could be used in Korea to make US involvement costly and difficult. This warning was followed on 8 July by CIA Intelligence Memorandum 302, which stated that the Soviets were responsible for the invasion, and they could use Chinese forces to intervene if DPRK forces could not stand up to UN forces.<ref name=Rose /> | ||

===Difficulty in collecting intelligence=== | ===Difficulty in collecting intelligence=== | ||

When the Korean War broke out in 1950, [[United States Army Special Forces]] did not yet exist, and there was a turf war over paramilitary actions between Willoughby's G-2 group and an interim group only partially under CIA control, the [[Office of Policy Coordination]] (OPC). A heavily censored history of CIA operations in Korea | When the Korean War broke out in 1950, [[United States Army Special Forces]] did not yet exist, and there was a turf war over paramilitary actions between Willoughby's G-2 group and an interim group only partially under CIA control, the [[Office of Policy Coordination]] (OPC). A heavily censored history of CIA operations in Korea | ||

| Line 80: | Line 81: | ||

|date=17 July 1968 | |date=17 July 1968 | ||

}}</ref> | }}</ref> | ||

shows that "Flight B" of the Fifth Air Force supported air support for both military and CIA special operations. When CIA | shows that "Flight B" of the Fifth Air Force supported air support for both military and CIA special operations. When CIA guerrillas were attacked in 1951-1952, the air unit had to adapt frequently changing schedules. According to the CIA history, "The US Air Force-CIA relationship during the war was particularly profitable, close, and cordial." Unconventional warfare, but not HUMINT, worked smoothly with the Army. Korea had been divided into CIA and Army regions, with the CIA in the extreme northeast, and the Army in the West. | ||

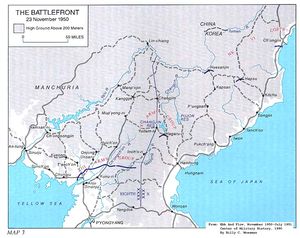

===Chinese intervention=== | |||

On 28 July, the CIA Weekly Summary had stated that 40,000 to 50,000 ethnic Korean soldiers from PLA units might soon reinforce DPRK forces." Again, the tactical warning of a Chinese force were rejected based on a strategic assessment of Soviet intentions <ref name=Rose /> | On 28 July, the CIA Weekly Summary had stated that 40,000 to 50,000 ethnic Korean soldiers from PLA units might soon reinforce DPRK forces." Again, the tactical warning of a Chinese force were rejected based on a strategic assessment of Soviet intentions <ref name=Rose /> | ||

Chairman Mao of the [[People's Republic of China]] (PRC) warned the U.S. not to travel north of the 38th parallel, yet the American forces invaded North Korea anyway on October 7. | Chairman Mao of the [[People's Republic of China]] (PRC) warned the U.S. not to travel north of the 38th parallel, yet the American forces invaded North Korea anyway on October 7. By November, the nature of the war had changed. | ||

<blockquote>"On 12 October, CIA Office of Records and Estimates Paper 58-50, entitled Critical Situations in The Far East—Threat of Full Chinese Communist Intervention in Korea, concluded that, “While full-scale Chinese Communist intervention in Korea must be regarded as a continuing possibility, a consideration of all known factors leads to the conclusion that barring a Soviet decision for global war, such action is not probable in 1950..." On 13 and 14 October, the 38th, 39th, and 40th Chinese Field Armies entered Korea. <ref name=Rose /></blockquote> | <blockquote>"On 12 October, CIA Office of Records and Estimates Paper 58-50, entitled Critical Situations in The Far East—Threat of Full Chinese Communist Intervention in Korea, concluded that, “While full-scale Chinese Communist intervention in Korea must be regarded as a continuing possibility, a consideration of all known factors leads to the conclusion that barring a Soviet decision for global war, such action is not probable in 1950..." On 13 and 14 October, the 38th, 39th, and 40th Chinese Field Armies entered Korea. <ref name=Rose /></blockquote> | ||

| Line 102: | Line 104: | ||

}}</ref> | }}</ref> | ||

It began with the estimate that "USSR-Satellite treatment of Korean developments indicates that they assess their current military and political position as one of great strength in comparison with that of the West, and that they propose to exploit the apparent conviction of the West of its own present weakness." At this time, there was no assumption that China and the USSR would differ on any policy "Moscow, seconded by | It began with the estimate that "USSR-Satellite treatment of Korean developments indicates that they assess their current military and political position as one of great strength in comparison with that of the West, and that they propose to exploit the apparent conviction of the West of its own present weakness." At this time, there was no assumption that China and the USSR would differ on any policy "Moscow, seconded by Beijing with regard to the Far East, has disclosed through a series of authoritative statements that it aims to achieve certain gains in the present situation: | ||

:a. Withdrawal of UN forces from Korea and of the Seventh Fleet from Formosan waters. | :a. Withdrawal of UN forces from Korea and of the Seventh Fleet from Formosan waters. | ||

| Line 110: | Line 112: | ||

"It can be anticipated that irrespective of any Western moves looking toward negotiations, assuming virtual Western surrender is not involved, the Kremlin plans a continuation of Chinese Communist pressure in Korea until the military defeat of the UN is complete. A determined and successful stand by UN forces in Korea would, of course, require a Soviet re-estimate of the situation." Such a stand did take place, and the war ended in a stalemate. | "It can be anticipated that irrespective of any Western moves looking toward negotiations, assuming virtual Western surrender is not involved, the Kremlin plans a continuation of Chinese Communist pressure in Korea until the military defeat of the UN is complete. A determined and successful stand by UN forces in Korea would, of course, require a Soviet re-estimate of the situation." Such a stand did take place, and the war ended in a stalemate. | ||

==Aftermath== | |||

While the [[Eighth United States Army]], assigned today to Korea as part of [[United States Forces Korea]], continues to reduce in size and will transition to support of the very competent ROK Army, it is worth noting that major components still assigned include a Military Intelligence Brigade with extensive technical sensors, as well as a Military Intelligence Battalion specializing in counterintelligence and [[human-source intelligence]]. | |||

National-level parts of the United States intelligence community continue monitoring North Korea, especially its guided missile and [[weapons of mass destruction]] efforts. Korea will never again be considered a low priority. | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{reflist|2}} | {{reflist|2}}[[Category:Suggestion Bot Tag]] | ||

Latest revision as of 13:42, 3 October 2024

When the army of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK, "North Korean" army. also NKPA) attacked the Republic of Korea (ROK, "South Korea") on June 15, 1950, it was a surprise to the United States and the Republic of Korea. In the case of the United States, the failure to anticipate may well have been the lack of senior government priority on the Korean Peninsula, and the still confused post-World War II U.S. intelligence structure. It is less clear why South Korea also was surprised at the highest levels. Still, the warnings were from relatively low-ranking levels and not definitive.

The last U.S. tactical units had left South Korea in 1949, leaving only the Korea Military Assistance Advisory Group (KMAG), which did not report to Douglas MacArthur, commanding Far Eastern Armed Forces. MacArthur had his own intelligence organization, "G-2", under MG Charles Willoughby, but FEAF G-2 did not have an explicit intelligence responsibility for Korea. The MAAG, reporting to the Pentagon, had the U.S. responsibility in the field. [1]

By 1949, the U.S. had concluded that withdrawing its occupation troops would probably lead to an invasion, but the Joint Chiefs of Staff did not want to fight in Korea, believing that the conditions would be too favorable to the other side. Essentially, Korea had been written off.

In mid-1949, however, Chief of Staff of the Army Omar Bradley had his staff develop a plan to bring the matter before the United Nations should there be an invasion, and, if diplomacy failed, form a UN multinational military force.

Failure to anticipate

Failure to anticipate the attack on the South was, in part, a result of the combined cutbacks in military and intelligence budgets after World War II, and the containment strategy against the Soviet bloc, which was principally focused on the Soviet Union itself, on China to a lesser extent, and essentially ignoring small bloc states such as North Korea. Schnabel suggests that this was only logical after the U.S. had written off Korea as strategically significant.

There was U.S. intelligence activity by the U.S. Korea Military Assistance Group (KMAG), who worked with ROK counterparts to analyze intelligence on North Korea. KMAG reported to Washington, not MacArthur. [1] It had the intelligence responsibility, sent reports to Washington, which sent it, along with CIA and other reports, to MacArthur. They sent this information to Washington periodically and on occasion made special reports. Other agencies and units in the Far East reported to appropriate officials in Washington. Communications intelligence monitored North Korean communications only to the extent that they provided information on Soviet activities.

An additional problem was that Douglas MacArthur wanted intelligence under his direct control. During the Second World War, he had not allowed the predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency, the Office of Strategic Services, to operate in his theater. U.S. intelligence, especially clandestine human-source intelligence, was in a bureaucratic limbo between 1945 and 1952, when the CIA obtained firm control of clandestine human-source intelligence and covert action.

Instead, he kept his own intelligence organization under his trusted intelligence officer, MG Charles Willoughby. In early 1950, General J. Lawton Collins asked MacArthur if he could provide information on areas outside his responsibility. MacArthur was reluctant to commit to regular reporting without orders to do so, but he thought he had the personnel to do so. [1]

"By late 1949, the KLO was reporting that the Communist guerrillas represented a serious threat to the Republic of Korea (ROK)..." Willoughby also claimed that the KLO had 16 agents operating in the North. KLO officers in Seoul, however, expressed suspicion regarding the loyalty and reporting of these agents. Separate from Willoughby's command, then-Capt. John Singlaub had established an Army intelligence outpost in Manchuria, just across the border from Korea. Over the course of several years, he trained and dispatched dozens of former Korean POWs, who had been in Japanese Army units, into the North. Their instructions were to join the Communist Korean military and government, and to obtain information on the Communists’ plans and intentions.

Still, CIA did have an analytic function under its control, and issued reports. While its 16 July 1949 Weekly Summary dismissed North Korea as a Soviet "puppet", the 29 October Summary suggested a North Korean attack on the South is possible as early as 1949, and cites reports of road improvements towards the border and troop movements there. [2]

"These reports establish the dominant theme in intelligence analysis from Washington that accounts for the failure to predict the North Korean attack—that the Soviets controlled North Korean decision making. The Washington focus on the Soviet Union as “the” Communist state had become the accepted perception within US Government’s political and military leadership circles. Any scholarly counterbalances to this view, either questioning the absolute authority of Moscow over other Communist states or noting that cultural, historic, or nationalistic factors might come into play, fell victim to the political atmosphere."

By April 1950, U.S. Army communications intelligence made a limited "search and development" study of DPRK traffic. CIA received its reports. The COMINT revealed large shipments of bandages and medicines from the USSR to North Korea and Manchuria, starting in February 1950. These two actions made sense only in hindsight, after the invasion of South Korea occurred in June 1950. [3]

By the spring of 1950, North Korea’s preparations for war had become...recognizable. Monthly CIA reports describe the military buildup of DPRK forces, but also discount the possibility of an actual invasion. It was believed that DPRK forces could not mount a successful attack without Soviet assistance, and such assistance would indicate a worldwide Communist offensive. There were no indications in Europe that such an offensive was in preparation. [2]

Some North Korean communications were intercepted between May 1949 and April 1950 because the operators were using Soviet communications procedures. Coverage was dropped once analysts confirmed the non-Soviet origin of the material. [3]

A surprise attack

In hindsight, there were warnings, in May-June 1950, of a potential attack in the near future. On 10 May, the South Korean Defense Ministry publicly warned at a press conference that DPRK troops were massing at the border and there was danger of an invasion...Throughout June, intelligence reports from South Korea and the CIA provide clear descriptions of DPRK preparations for war. These reports noted the removal of civilians from the border area, the restriction of all transport capabilities for military use only, and the movements of infantry and armor units to the border area. Also, following classic Communist political tactics, the DPRK began an international propaganda campaign against the ROK police state. [3]

On 6 June, CIA informed U.S. policymakers that all East Asian senior Soviet diplomats were recalled to Moscow for consultations. Unfortunately, it was assumed this was to consult about a new plan to counter anti-Communist efforts in the region. On 20 June 1950, the CIA published a report, based primarily on HUMINT, concluding that the DPRK had the capability to invade the South at any time. President Harry S. Truman, United States Secretary of State Dean Acheson, and United States Secretary of Defense Louis Johnson all received copies of this report. [2]

On June 25, 1950, Kim Il Sung, the leader of Communist North Korea, sent troops of the North Korean People’s Army (NKPA) across the 38th parallel and invaded South Korea, heading toward its capital, Seoul.

MacArthur's headquarters "learned of the attack six and one-half hours after the first North Korean troops crossed into South Korea. The telegram bearing the news from the Office of the Military Attaché in Seoul reported:

Fighting with great intensity started at 0400, 25 June on the Ongjin Peninsula, moving eastwardly taking six major points; city of Kaesong fell to North Koreans at 0900, ten tanks slightly north of Chunchon, landing twenty boats approximately one regiment strength on east coast reported cutting coastal road south of Kangnung; Comment: No evidence of panic among South Korean troops.

A message ninety minutes later gave confirmation. General MacArthur immediately informed Washington and, within a few hours, sent the first comprehensive situation report on the Korean fighting."[1]

Early intelligence analysis

CIA intelligence reports, after the invasion, still treated North Korea as controlled by the USSR, but the reports did raise the possibility of Chinese involvement. On 26 June, CIA agreed with the US Embassy in Moscow that the North Korean offensive was a “... clear-cut Soviet challenge to the United States…”

..the perception existed that only the Soviets could order an invasion by a “client state” and that such an act would be a prelude to a world war. Washington was confident that the Soviets were not ready to take such a step..." is clearly stated in a 19 June CIA paper on DRPK military capabilities. The paper said that “The DPRK is a firmly controlled Soviet satellite that exercises no independent initiative and depends entirely on the support of the USSR for existence.”

CIA, the State Department, and the three service intelligence agencies agreed with this estimate.

"...General MacArthur and his staff refused to believe that any Asians would risk facing certain defeat by threatening American interests. This belief caused them to ignore warnings of the DPRK military buildup and mobilization near the border, clearly the “force protection” intelligence that should have been most alerting to military minds. It was a strong and perhaps arrogantly held belief, which did not weaken even in the face of DPRK military successes against US troops in the summer of 1950.[2]

On 30 June 1950, [as] President Truman authorized the use of US ground forces in Korea, CIA Intelligence Memorandum 301, Estimate of Soviet Intentions and Capabilities for Military Aggression, warned that the Soviets could commit large numbers of Chinese troops, which could be used in Korea to make US involvement costly and difficult. This warning was followed on 8 July by CIA Intelligence Memorandum 302, which stated that the Soviets were responsible for the invasion, and they could use Chinese forces to intervene if DPRK forces could not stand up to UN forces.[2]

Difficulty in collecting intelligence

When the Korean War broke out in 1950, United States Army Special Forces did not yet exist, and there was a turf war over paramilitary actions between Willoughby's G-2 group and an interim group only partially under CIA control, the Office of Policy Coordination (OPC). A heavily censored history of CIA operations in Korea [4] shows that "Flight B" of the Fifth Air Force supported air support for both military and CIA special operations. When CIA guerrillas were attacked in 1951-1952, the air unit had to adapt frequently changing schedules. According to the CIA history, "The US Air Force-CIA relationship during the war was particularly profitable, close, and cordial." Unconventional warfare, but not HUMINT, worked smoothly with the Army. Korea had been divided into CIA and Army regions, with the CIA in the extreme northeast, and the Army in the West.

Chinese intervention

On 28 July, the CIA Weekly Summary had stated that 40,000 to 50,000 ethnic Korean soldiers from PLA units might soon reinforce DPRK forces." Again, the tactical warning of a Chinese force were rejected based on a strategic assessment of Soviet intentions [2]

Chairman Mao of the People's Republic of China (PRC) warned the U.S. not to travel north of the 38th parallel, yet the American forces invaded North Korea anyway on October 7. By November, the nature of the war had changed.

"On 12 October, CIA Office of Records and Estimates Paper 58-50, entitled Critical Situations in The Far East—Threat of Full Chinese Communist Intervention in Korea, concluded that, “While full-scale Chinese Communist intervention in Korea must be regarded as a continuing possibility, a consideration of all known factors leads to the conclusion that barring a Soviet decision for global war, such action is not probable in 1950..." On 13 and 14 October, the 38th, 39th, and 40th Chinese Field Armies entered Korea. [2]

CIA reporting from Tokyo, based on information obtained from a former Chinese Nationalist officer sent into Manchuria to contact former colleagues now in the Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA), stated that the PLA had over 300,000 troops in the border area. A CIA-led irregular ROK force operating on the west coast near the Yalu river reported, on October 15, that Chinese troops were moving into Korea.

All this information subsequently turned out to be accurate. At that meeting, on 15 October, MacArthur told Truman there was little chance of a large-scale Chinese intervention. And, he noted, should it occur, his air power would destroy any Chinese forces that appeared.

The next day, the CIA Daily Summary reported that the US Embassy in The Hague had been advised that Chinese troops had moved into Korea. At this point, the analytic perspective of the Agency shifted somewhat... The Agency also abandoned the position that the Chinese had the capability to intervene but would not do so, and began to accept that the Chinese had entered Korea. But it held firm to its view that China had no intention of entering the war in any large-scale fashion.[2]

US analysis in the winter

In December 1950, with the Korean War in progress, the Central Intelligence Agency issued National Intelligence Estimate 15: "Probable Soviet Moves to Exploit the Present Situation". [5]

It began with the estimate that "USSR-Satellite treatment of Korean developments indicates that they assess their current military and political position as one of great strength in comparison with that of the West, and that they propose to exploit the apparent conviction of the West of its own present weakness." At this time, there was no assumption that China and the USSR would differ on any policy "Moscow, seconded by Beijing with regard to the Far East, has disclosed through a series of authoritative statements that it aims to achieve certain gains in the present situation:

- a. Withdrawal of UN forces from Korea and of the Seventh Fleet from Formosan waters.

- b. Establishment of Communist China as the predominant power in the Far East, including the seating of Communist China in the United Nations.

- c.Reduction of Western control over Japan as a step toward its eventual elimination.

- d. Prevention of West German rearmament.

"It can be anticipated that irrespective of any Western moves looking toward negotiations, assuming virtual Western surrender is not involved, the Kremlin plans a continuation of Chinese Communist pressure in Korea until the military defeat of the UN is complete. A determined and successful stand by UN forces in Korea would, of course, require a Soviet re-estimate of the situation." Such a stand did take place, and the war ended in a stalemate.

Aftermath

While the Eighth United States Army, assigned today to Korea as part of United States Forces Korea, continues to reduce in size and will transition to support of the very competent ROK Army, it is worth noting that major components still assigned include a Military Intelligence Brigade with extensive technical sensors, as well as a Military Intelligence Battalion specializing in counterintelligence and human-source intelligence.

National-level parts of the United States intelligence community continue monitoring North Korea, especially its guided missile and weapons of mass destruction efforts. Korea will never again be considered a low priority.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Schnabel, James F. (1972), United States Army in the Korean War, Policy and Direction: the First Year, Center for Military History, U.S. Department of the Army

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Rose, P.K., "Two Strategic Intelligence Mistakes in Korea, 1950: Perceptions and Reality", Studies in Intelligence

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Hatch, David A., The Korean War: The SIGINT Background, National Security Agency

- ↑ Central Intelligence Agency (17 July 1968), Clandestine Services History: The Secret War in Korea 1950-1952

- ↑ Central Intelligence Agency (11 December 1950), National Intelligence Estimate NIE-15: Probable Soviet Moves to Exploit the Present Situation