World War II, air war, European Theater strategic operations: Difference between revisions

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz No edit summary |

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz No edit summary |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

It should be understood that the European Theater strategic campaign began with small British raids in 1940, during the [[Battle of Britain]], but major bombing programs continued from 1942 to the end of the war. During that time, there were various parallel efforts, such as the [[World War II, air war, Allied offensive counter-air campaign|1944 offensive counter-air campaign]] and the [[World War II, air war, Mediterranean and European tactical operations|support of ground operations]], including preparing for invasions as well as well as [[close air support]] and [[battlefield air interdiction]]. | It should be understood that the European Theater strategic campaign began with small British raids in 1940, during the [[Battle of Britain]], but major bombing programs continued from 1942 to the end of the war. During that time, there were various parallel efforts, such as the [[World War II, air war, Allied offensive counter-air campaign|1944 offensive counter-air campaign]] and the [[World War II, air war, Mediterranean and European tactical operations|support of ground operations]], including preparing for invasions as well as well as [[close air support]] and [[battlefield air interdiction]]. | ||

===Technology | ===Anglo-American=== | ||

British and American strategic bombing advocates had different paradigms of what is, today, called [[air warfare planning#strategic strike|strategic strike]]. This resulted in different aircraft designs, training, targeting, and operational techniques. The Royal Air Force (RAF) had its own strategic bombing campaign, so a division of labor was agreed on whereby the RAF flew missions at night with [[Vickers Wellington]] bombers, which carried more bombs but had much less defensive capability than the B-17. The better-protected U.S. bombers flew daytime missions. | |||

The Pacific operation was essentially American. While there was a generally shared doctrinal concept, the problems of conducting effective strategic bombing was different: the supporting actor award went to the [[amphibious warfare|amphibious warriors]] of the [[United States Navy]], [[United States Marine Corps]], and [[United States Army]], who captured and rebuilt the airfields needed to reach the Japanese home islands. | |||

Had the war in Europe lasted longer, although some claim the nuclear weapons were saved, for "racial" reasons, against Japan, had the weapons been ready and there was not the same confidence in ground victory, they would have been used. For that reason, the article [[World War II, Air War, nuclear warfare]] deals first with the concept of nuclear warfare as then understood and the [[Manhattan Project]] to develop them. It deals with the decision to use them on Japan, and the mechanics of that operation, because Japan was the only available target when the first bombs were available. | |||

===Russian=== | |||

The Russians never spent significant development on long-range aviation. Perhaps their outstanding design was the [[Il-2 Stormovik]], a heavily armored, heavily armoed ground support and antitank aircraft, which was an inspiration for the much later U.S. [[A-10 Thunderbolt II]]. | |||

===German=== | |||

Hitler was insistent on bombers having tactical capability, which meant dive bombing at the time, a maneuver impossible for any heavy bomber of the time. His aircraft had limited effect on Britain for a variety of reasons, but low payload certainly was among them | |||

====Manned bombers==== | |||

The most basic reason that Germany achieved little in strategic bombing was that they never produced quantities of an appropriate heavy bomber. Early in the war, they had excellent tactical aviation, but when they first faced an [[integrated air defense system]], their essentially medium bombers did not have the numbers or bombload to do major damage to Great Britain. | |||

====Failure of German secret weapons==== | |||

Hitler tried to sustain morale by promising that "secret weapons" would turn the war around. He did indeed have the weapons. The first of 9,300 [[V-1]] flying bombs hit London in mid- June, 1944, and together with 1,300 [[V-2]] rockets caused 8,000 civilian deaths and 23,000 injuries. Although they did not seriously undercut British morale or munitions production, they bothered the British government a great deal--Germany now had its own unanswered weapons system. Using proximity fuzes, British ack-ack gunners (many of them women) learned how to shoot down the 400 mph V-1s; nothing could stop the supersonic V-2s. The British government, in near panic, demanded that upwards of 40% of bomber sorties be targeted against the launch sites, and got its way in "Operation CROSSBOW." The attacks were futile, and the diversion represented a major success for Hitler. In early 1943 the strategic bombers were directed against U- boat pens, which were easy to reach and which represented a major strategic threat to Allied logistics. However, the pens were very solidly built--it took 7,000 flying hours to destroy one sub there, about the same effort that it took to destroy one-third of Cologne. The antisubmarine campaign thus was a victory for Hitler.<ref> Webster & Franklin, 4:24</ref> | |||

Every raid against a V-1 or V-2 launch site was one less raid against the Third Reich. On the whole, however, the secret weapons were still another case of too little too late. The Luftwaffe ran the V-1 program, which used a jet engine, but it diverted scarce engineering talent and manufacturing capacity that were urgently needed to improve German radar, air defense, and jet fighters. The German Army ran the V-2 program. The rockets were a technological triumph, and bothered the British leadership even more than the V-1s. But they were so inaccurate they rarely could hit militarily significant targets. | |||

Furthermore, the program used up scarce technical resources that could have gone into the development of air defense weapons like proximity fuzes and "Waterfall," a deadly ground-to-air rocket. The secret weapon of greatest threat to the Allies was the jet plane that could outfly Allied fighters and shoot down bombers. The Messerschmitt ME-262 prototype flew in 1939, but was never given high priority until too late. Hitler never understood air power; his personal interference repeatedly delayed the jets. First he proclaimed they would not be necessary, then insisted they be redesigned as bombers to make retaliation raids against London. The Luftwaffe would have been a much more deadly threat if it built ten thousand jets; it only made one thousand and they rarely flew combat missions. | |||

==Technology== | |||

Significant areas of technology included aircraft, navigational and bombing equipment, bombs, and defensive systems. These have to be assessed against the German [[Kammhuber Line integrated air defense system]]; aside from forcible attacks against air defense, there was a constant electronic warfare measure-countermeasure duel. | Significant areas of technology included aircraft, navigational and bombing equipment, bombs, and defensive systems. These have to be assessed against the German [[Kammhuber Line integrated air defense system]]; aside from forcible attacks against air defense, there was a constant electronic warfare measure-countermeasure duel. | ||

| Line 31: | Line 49: | ||

| European | | European | ||

| Escort fighter with range to heart of German | | Escort fighter with range to heart of German | ||

|} | |} | ||

[[Image:B17-G.jpg|right|thumb|350px|a B-17G]] | [[Image:B17-G.jpg|right|thumb|350px|a B-17G]] | ||

| Line 46: | Line 59: | ||

Marshall and King did not fully accept the doctrine of strategic bombing. They insisted that control of the air would always be supplementary, and they much preferred tactical air. Furthermore, they denied that strategic bombing of the enemy's industrial strength would be decisive in warfare. Marshall accepted AWPD-1 as a blueprint for airplane acquisition and force levels (it proved astonishingly accurate), but refused to believe that strategic bombing could be decisive, noting "an almost invariable rule that only armies can win wars." Secretary of War Stimson, who usually backed Marshall 100%, disagreed this time: "I fear Marshall and his deputies are very much wedded to the theory that it is merely an auxiliary force." The debate between the AAF and the Army and Navy resulted in a compromise: both strategic and tactical air power would be used. The production of planes (AAF, Navy, Marines) was split about equally between strategic and tactical air, with 44% going to strategic bombers (especially the [[B-17]] and [[B-29]]), 24% going to tactical ground-support and interdiction bombers (medium land-based Army and Marine, and and light carrier-based Navy planes), and 20% to fighters (which could either escort strategic bombers or be used as tactical air.) The remainder went for transports, trainers, and unarmed reconnaissance planes. Arnold kept to the compromise, and did provide Marshall with ample tactical air power, but with the proviso that his airmen would always decide on how, when and where it was to be used. In the boldest move for AAF autonomy, Arnold gained almost complete control over the strategic bombing campaigns against Japan and Germany. Nimitz and MacArthur, therefore, shared control of the Pacific war with Arnold in Washington, while Eisenhower shared control of the European war with Arnold. Secretary of War Stimson, however, trumped them all when he kept control of the atomic bomb in his own hands. | Marshall and King did not fully accept the doctrine of strategic bombing. They insisted that control of the air would always be supplementary, and they much preferred tactical air. Furthermore, they denied that strategic bombing of the enemy's industrial strength would be decisive in warfare. Marshall accepted AWPD-1 as a blueprint for airplane acquisition and force levels (it proved astonishingly accurate), but refused to believe that strategic bombing could be decisive, noting "an almost invariable rule that only armies can win wars." Secretary of War Stimson, who usually backed Marshall 100%, disagreed this time: "I fear Marshall and his deputies are very much wedded to the theory that it is merely an auxiliary force." The debate between the AAF and the Army and Navy resulted in a compromise: both strategic and tactical air power would be used. The production of planes (AAF, Navy, Marines) was split about equally between strategic and tactical air, with 44% going to strategic bombers (especially the [[B-17]] and [[B-29]]), 24% going to tactical ground-support and interdiction bombers (medium land-based Army and Marine, and and light carrier-based Navy planes), and 20% to fighters (which could either escort strategic bombers or be used as tactical air.) The remainder went for transports, trainers, and unarmed reconnaissance planes. Arnold kept to the compromise, and did provide Marshall with ample tactical air power, but with the proviso that his airmen would always decide on how, when and where it was to be used. In the boldest move for AAF autonomy, Arnold gained almost complete control over the strategic bombing campaigns against Japan and Germany. Nimitz and MacArthur, therefore, shared control of the Pacific war with Arnold in Washington, while Eisenhower shared control of the European war with Arnold. Secretary of War Stimson, however, trumped them all when he kept control of the atomic bomb in his own hands. | ||

==Early efforts, 1942== | |||

The American strategic bombing campaign against Germany was operated in parallel with RAF Bomber Command, which fervently believed in its own version of strategic bombing doctrine. The AAF bombed during the day, the RAF at night, when interception was difficult. Nightime navigation was so poor that the RAF quickly gave up precision bombing; their real target was the morale of the people who lived in the largest cities. According to Air Marshal Harris of RAF Bomber Command massive nightly raids would eventually burn out all the major German cities. The populace might survive in shelters, but they would be "dehoused", and lose confidence in the Fuehrer, which would lead to loss of German will to resist. Furthermore, the factories and railroad system would eventually be burned out as well. The British were willing to spend 30% of their GNP on Bomber Command, in order to weaken Germany, gain revenge, and avoid the high infantry casualties such as the Soviets were enduring.<ref> .. Werrell 707 </ref> Strategic bombing did "dehouse" 7.5 million Germans, but it hardly mattered, for the target cities had a surplus of housing (because most young men were away the army, most civilians had evacuated to the countryside, and all Jews sent to death camps and their apartments seized.) As the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey reported after the war, "Allied bombing widely and seriously depressed German morale, but depressed as discouraged workers were not necessarily unproductive workers." The German civilian air defense system enrolled 22 million volunteers, supervised by 75,000 full-time officials. Focusing on basement shelters in residential districts in the cities, the Germans built interconnected passageways, painted on fire retardants, and stored emergency supplies. The Gestapo, making tens of thousands of arrests, made certain that discontent was kept unfocused. Bombs did occasionally damage factories, but fast repairs were made. Rare indeed was the bomb dropped from 20,000 feet that destroyed a steel machine tool, especially when the bombadier had only the vaguest idea where it was or where he was. | The American strategic bombing campaign against Germany was operated in parallel with RAF Bomber Command, which fervently believed in its own version of strategic bombing doctrine. The AAF bombed during the day, the RAF at night, when interception was difficult. Nightime navigation was so poor that the RAF quickly gave up precision bombing; their real target was the morale of the people who lived in the largest cities. According to Air Marshal Harris of RAF Bomber Command massive nightly raids would eventually burn out all the major German cities. The populace might survive in shelters, but they would be "dehoused", and lose confidence in the Fuehrer, which would lead to loss of German will to resist. Furthermore, the factories and railroad system would eventually be burned out as well. The British were willing to spend 30% of their GNP on Bomber Command, in order to weaken Germany, gain revenge, and avoid the high infantry casualties such as the Soviets were enduring.<ref> .. Werrell 707 </ref> Strategic bombing did "dehouse" 7.5 million Germans, but it hardly mattered, for the target cities had a surplus of housing (because most young men were away the army, most civilians had evacuated to the countryside, and all Jews sent to death camps and their apartments seized.) As the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey reported after the war, "Allied bombing widely and seriously depressed German morale, but depressed as discouraged workers were not necessarily unproductive workers." The German civilian air defense system enrolled 22 million volunteers, supervised by 75,000 full-time officials. Focusing on basement shelters in residential districts in the cities, the Germans built interconnected passageways, painted on fire retardants, and stored emergency supplies. The Gestapo, making tens of thousands of arrests, made certain that discontent was kept unfocused. Bombs did occasionally damage factories, but fast repairs were made. Rare indeed was the bomb dropped from 20,000 feet that destroyed a steel machine tool, especially when the bombadier had only the vaguest idea where it was or where he was. | ||

===Gaining Allied air supremacy in Europe=== | ===Gaining Allied air supremacy in Europe, 1943=== | ||

In late 1943 the AAF suddenly realized the need to revise its basic doctrine: strategic bombing against a technologically sophisticated enemy like Germany was impossible without air supremacy. While strategic bombing against the aircraft and petroleum industry helped, to achieve air supremacy in a reasonable time, that had to be done with a deliberate attack on the Luftwaffe. In modern terms, General Arnold realized that it was necessary to conduct an [[air warfare planning#offensive counter-air|offensive counter-air]] campaign. See [[World War II, Allied offensive counter-air campaign]]. | In late 1943 the AAF suddenly realized the need to revise its basic doctrine: strategic bombing against a technologically sophisticated enemy like Germany was impossible without air supremacy. While strategic bombing against the aircraft and petroleum industry helped, to achieve air supremacy in a reasonable time, that had to be done with a deliberate attack on the Luftwaffe. In modern terms, General Arnold realized that it was necessary to conduct an [[air warfare planning#offensive counter-air|offensive counter-air]] campaign. See [[World War II, Allied offensive counter-air campaign]]. | ||

Neither Germany nor Japan nor the Soviets built a strategic bomber force. The Germans had some theoretical ideas about a [[submarine-launched ballistic missile]], but it never got to the stage of a prototype; they put a great deal of effort, misplaced in hindsight, into "Vengeance weapons": the V-1 and V-2 missiles, the never-implmented V-3, and more exotic weapons still on the drawing boards. | |||

==strategic bombing results== | |||

===Destroying Germany's Oil and Transportation=== | |||

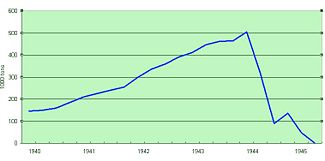

Besides knocking out the Luftwaffe, the second most striking achievement of the strategic bombing campaign was the destruction of the German oil supply. Oil was essential for U-boats and tanks, while very high quality aviation gasoline was essential for piston planes.<ref> Jet planes ran on cheap kerosene, and rockets used plain alcohol; the railroad system used coal, which was in abundant supply.</ref> Germany had few wells, and depended on imports from Russia (before 1941) and Nazi ally Romania, and on synthetic oil plants that used chemical processes to turn coal into oil. Heedless of the risk of Allied bombing, the Germans had carelessly concentrated 80% of synthetic oil production in just 20 plants. These became a top priority for the AAF and RAF in 1944, and were targets for 210,000 tons of bombs. The oil plants were very hard to hit, but also hard to repair. As graph #1 shows, the bombings dried up the oil supply in the summer of 1944. An extreme oil emergency followed, which grew worse month by month. | |||

[[Image:German-aviation-gas-ww2.jpg|thumb|325px|Germany's supply of aviation gasoline 1940-45]] | |||

The third notable achievement of the bombing campaign was the degradation of the German transportation system--its railroads and canals (there was little truck traffic.) In the two months before and after D-Day the American Liberators (B-24), Flying Fortresses and British Lancasters hammered away at the French railroad system. Underground Resistance fighters sabotaged some 350 locomotives and 15,000 freight cars every month. Critical bridges and tunnels were cut by bombing or sabotage. Berlin responded by sending in 60,000 German railway workers, but even they took two or three days to reopen a line after heavy raids on switching yards. The system deteriorated quickly, and it proved incapable of carrying reinforcements and supplies to oppose the Normandy invasion. To that extent the assignment of strategic bombers to the tactical job of interdiction was successful. When Bomber Command hit German cities, it inevitably hit some railroad yards. The AAF made railroad yards a high priority, and gave considerable attention as well to bridges, moving trains, ferries, and other choke points. The "transportation policy" of targeting the railroad system came in for intense debate among Allied strategists. It was argued that enemy had the densest and best operated railway system in the world, and one with a great deal of slack. The Nazis systematically looted rolling stock from conquered nations, so they always had plenty of locomotives and freight cars. Furthermore, most traffic was "civilian," and urgent troop train traffic would always get through. The critics exaggerated the resilience of the German system. As wave after wave of bombers blasted away, repairs took longer and longer. Delays became longer and more frustrating. Yes, the troop trains usually got through, but the "civilian" traffic that did not get through comprised food, uniforms, medical equipment, horses, fodder, tanks, fuel, howitzers, flak shells and machine guns for the front lines, and coal, steel, spare parts, subassemblies, and critical components for munitions factories. By January, 1945, the transportation system was cracking in dozens of places, and front-line units had more luck trying to capture Allied weapons than waiting for fresh supplies of their own. | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{reflist|2}} | {{reflist|2}} | ||

Revision as of 10:16, 21 August 2008

- See also: World War II, air war, Allied offensive counter-air campaign

- See also: World War II, air war, Mediterranean and European tactical operations

- See also: Battle of the Atlantic

British and American strategic bombing advocates had different paradigms of what is, today, called strategic strike. This resulted in different aircraft designs, training, targeting, and operational techniques.

It should be understood that the European Theater strategic campaign began with small British raids in 1940, during the Battle of Britain, but major bombing programs continued from 1942 to the end of the war. During that time, there were various parallel efforts, such as the 1944 offensive counter-air campaign and the support of ground operations, including preparing for invasions as well as well as close air support and battlefield air interdiction.

Anglo-American

British and American strategic bombing advocates had different paradigms of what is, today, called strategic strike. This resulted in different aircraft designs, training, targeting, and operational techniques. The Royal Air Force (RAF) had its own strategic bombing campaign, so a division of labor was agreed on whereby the RAF flew missions at night with Vickers Wellington bombers, which carried more bombs but had much less defensive capability than the B-17. The better-protected U.S. bombers flew daytime missions.

The Pacific operation was essentially American. While there was a generally shared doctrinal concept, the problems of conducting effective strategic bombing was different: the supporting actor award went to the amphibious warriors of the United States Navy, United States Marine Corps, and United States Army, who captured and rebuilt the airfields needed to reach the Japanese home islands.

Had the war in Europe lasted longer, although some claim the nuclear weapons were saved, for "racial" reasons, against Japan, had the weapons been ready and there was not the same confidence in ground victory, they would have been used. For that reason, the article World War II, Air War, nuclear warfare deals first with the concept of nuclear warfare as then understood and the Manhattan Project to develop them. It deals with the decision to use them on Japan, and the mechanics of that operation, because Japan was the only available target when the first bombs were available.

Russian

The Russians never spent significant development on long-range aviation. Perhaps their outstanding design was the Il-2 Stormovik, a heavily armored, heavily armoed ground support and antitank aircraft, which was an inspiration for the much later U.S. A-10 Thunderbolt II.

German

Hitler was insistent on bombers having tactical capability, which meant dive bombing at the time, a maneuver impossible for any heavy bomber of the time. His aircraft had limited effect on Britain for a variety of reasons, but low payload certainly was among them

Manned bombers

The most basic reason that Germany achieved little in strategic bombing was that they never produced quantities of an appropriate heavy bomber. Early in the war, they had excellent tactical aviation, but when they first faced an integrated air defense system, their essentially medium bombers did not have the numbers or bombload to do major damage to Great Britain.

Failure of German secret weapons

Hitler tried to sustain morale by promising that "secret weapons" would turn the war around. He did indeed have the weapons. The first of 9,300 V-1 flying bombs hit London in mid- June, 1944, and together with 1,300 V-2 rockets caused 8,000 civilian deaths and 23,000 injuries. Although they did not seriously undercut British morale or munitions production, they bothered the British government a great deal--Germany now had its own unanswered weapons system. Using proximity fuzes, British ack-ack gunners (many of them women) learned how to shoot down the 400 mph V-1s; nothing could stop the supersonic V-2s. The British government, in near panic, demanded that upwards of 40% of bomber sorties be targeted against the launch sites, and got its way in "Operation CROSSBOW." The attacks were futile, and the diversion represented a major success for Hitler. In early 1943 the strategic bombers were directed against U- boat pens, which were easy to reach and which represented a major strategic threat to Allied logistics. However, the pens were very solidly built--it took 7,000 flying hours to destroy one sub there, about the same effort that it took to destroy one-third of Cologne. The antisubmarine campaign thus was a victory for Hitler.[1]

Every raid against a V-1 or V-2 launch site was one less raid against the Third Reich. On the whole, however, the secret weapons were still another case of too little too late. The Luftwaffe ran the V-1 program, which used a jet engine, but it diverted scarce engineering talent and manufacturing capacity that were urgently needed to improve German radar, air defense, and jet fighters. The German Army ran the V-2 program. The rockets were a technological triumph, and bothered the British leadership even more than the V-1s. But they were so inaccurate they rarely could hit militarily significant targets.

Furthermore, the program used up scarce technical resources that could have gone into the development of air defense weapons like proximity fuzes and "Waterfall," a deadly ground-to-air rocket. The secret weapon of greatest threat to the Allies was the jet plane that could outfly Allied fighters and shoot down bombers. The Messerschmitt ME-262 prototype flew in 1939, but was never given high priority until too late. Hitler never understood air power; his personal interference repeatedly delayed the jets. First he proclaimed they would not be necessary, then insisted they be redesigned as bombers to make retaliation raids against London. The Luftwaffe would have been a much more deadly threat if it built ten thousand jets; it only made one thousand and they rarely flew combat missions.

Technology

Significant areas of technology included aircraft, navigational and bombing equipment, bombs, and defensive systems. These have to be assessed against the German Kammhuber Line integrated air defense system; aside from forcible attacks against air defense, there was a constant electronic warfare measure-countermeasure duel.

| Country and aircraft | Theater | Features and liabilities |

|---|---|---|

| U.K. Avro Lancaster | European | Heaviest bombload in Europe; little defense |

| U.S. B-17 Flying Fortress | European | Light bombload in its class, strong defense |

| U.S. B-24 Liberator | European, Atlantic & Mediterranean | Moderate bombload, long range |

| U.S. P-51 Mustang | European | Escort fighter with range to heart of German |

The B-17, nicknamed the "Flying Fortress" was a heavy bomber that was the workhorse, along with the B-24, of America's strategic bombing of Germany in World War II. The United States Army Air Forces (AAF) considered the B-17 the perfect embodiment of its strategic bombing doctrine because of its long range, its ability to defend itself, and its Norden bombsight.

The airmen, while delighted with the greatly enhanced importance of air power implied by the emphasis on tactical air supremacy, in fact had a quite different doctrine regarding how air power could best be applied. It was "strategic bombing." Do not be misled by tanks and artillery and infantry, they insisted- -that was ancient history. The war could be won hundreds or thousands of miles behind the front lines--an invasion would be unnecessary because the bombers alone could defeat Germany and Japan. Modern warfare depended upon industrial production in large, fixed, visible factories, oil refineries and electric power stations. As Lovett explained, "Our main job is to carry the war to the country of the people fighting us--to make their working conditions as intolerable as possible, to destroy their plants, their sources of electric power, their communications system."[2] Strategic bombing was "guaranteed" to destroy those installations sooner or later. To win the war, therefore, it was necessary merely to build up a strategic air force from suitable bases. In Europe, the enemy was within attack range of B-17 bases in Britain and Italy. Matters were more complicated in the Pacific, where the Rising Sun flew above all the islands within range of Tokyo. Perhaps suitable bases could be built in China; a very-long-range bomber for those bases, the B-29, went into mass production. Closer and more secure bases could be built in the Mariana Islands (Saipan, Guam, Tinian), which therefore were invaded in June 1944.

In August, 1941, the AAF devised AWPD-1, its plan to win the war through air power alone (an appendix discussed tactical support for an invasion, should that prove necessary.) AWPD-1 read like an engineering document, and focused on the choke points of the German war economy. It listed 154 German targets in order of priority (electric power, railroad yards and bridges, synthetic oil plants, aircraft factories). By assuming half the bombs would land within 400 yards of their targets, it concluded that 3,800 bombers could finish the job in six months time. A total of 62,000 combat planes, and 37,000 trainers would have to be built. AWPD-42, completed a year later, provided more tactical air power, proposed a detailed strategic air war against Japan, and reaffirmed the same German targets (plus submarine yards). The summit conference at Casablanca in January, 1943, accepted the basic plan of AWPD-42: Germany and Japan would be the targets of massive strategic bombing that would either force their surrender or soften them up for an infantry invasion.[3]

Marshall and King did not fully accept the doctrine of strategic bombing. They insisted that control of the air would always be supplementary, and they much preferred tactical air. Furthermore, they denied that strategic bombing of the enemy's industrial strength would be decisive in warfare. Marshall accepted AWPD-1 as a blueprint for airplane acquisition and force levels (it proved astonishingly accurate), but refused to believe that strategic bombing could be decisive, noting "an almost invariable rule that only armies can win wars." Secretary of War Stimson, who usually backed Marshall 100%, disagreed this time: "I fear Marshall and his deputies are very much wedded to the theory that it is merely an auxiliary force." The debate between the AAF and the Army and Navy resulted in a compromise: both strategic and tactical air power would be used. The production of planes (AAF, Navy, Marines) was split about equally between strategic and tactical air, with 44% going to strategic bombers (especially the B-17 and B-29), 24% going to tactical ground-support and interdiction bombers (medium land-based Army and Marine, and and light carrier-based Navy planes), and 20% to fighters (which could either escort strategic bombers or be used as tactical air.) The remainder went for transports, trainers, and unarmed reconnaissance planes. Arnold kept to the compromise, and did provide Marshall with ample tactical air power, but with the proviso that his airmen would always decide on how, when and where it was to be used. In the boldest move for AAF autonomy, Arnold gained almost complete control over the strategic bombing campaigns against Japan and Germany. Nimitz and MacArthur, therefore, shared control of the Pacific war with Arnold in Washington, while Eisenhower shared control of the European war with Arnold. Secretary of War Stimson, however, trumped them all when he kept control of the atomic bomb in his own hands.

Early efforts, 1942

The American strategic bombing campaign against Germany was operated in parallel with RAF Bomber Command, which fervently believed in its own version of strategic bombing doctrine. The AAF bombed during the day, the RAF at night, when interception was difficult. Nightime navigation was so poor that the RAF quickly gave up precision bombing; their real target was the morale of the people who lived in the largest cities. According to Air Marshal Harris of RAF Bomber Command massive nightly raids would eventually burn out all the major German cities. The populace might survive in shelters, but they would be "dehoused", and lose confidence in the Fuehrer, which would lead to loss of German will to resist. Furthermore, the factories and railroad system would eventually be burned out as well. The British were willing to spend 30% of their GNP on Bomber Command, in order to weaken Germany, gain revenge, and avoid the high infantry casualties such as the Soviets were enduring.[4] Strategic bombing did "dehouse" 7.5 million Germans, but it hardly mattered, for the target cities had a surplus of housing (because most young men were away the army, most civilians had evacuated to the countryside, and all Jews sent to death camps and their apartments seized.) As the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey reported after the war, "Allied bombing widely and seriously depressed German morale, but depressed as discouraged workers were not necessarily unproductive workers." The German civilian air defense system enrolled 22 million volunteers, supervised by 75,000 full-time officials. Focusing on basement shelters in residential districts in the cities, the Germans built interconnected passageways, painted on fire retardants, and stored emergency supplies. The Gestapo, making tens of thousands of arrests, made certain that discontent was kept unfocused. Bombs did occasionally damage factories, but fast repairs were made. Rare indeed was the bomb dropped from 20,000 feet that destroyed a steel machine tool, especially when the bombadier had only the vaguest idea where it was or where he was.

Gaining Allied air supremacy in Europe, 1943

In late 1943 the AAF suddenly realized the need to revise its basic doctrine: strategic bombing against a technologically sophisticated enemy like Germany was impossible without air supremacy. While strategic bombing against the aircraft and petroleum industry helped, to achieve air supremacy in a reasonable time, that had to be done with a deliberate attack on the Luftwaffe. In modern terms, General Arnold realized that it was necessary to conduct an offensive counter-air campaign. See World War II, Allied offensive counter-air campaign. Neither Germany nor Japan nor the Soviets built a strategic bomber force. The Germans had some theoretical ideas about a submarine-launched ballistic missile, but it never got to the stage of a prototype; they put a great deal of effort, misplaced in hindsight, into "Vengeance weapons": the V-1 and V-2 missiles, the never-implmented V-3, and more exotic weapons still on the drawing boards.

strategic bombing results

Destroying Germany's Oil and Transportation

Besides knocking out the Luftwaffe, the second most striking achievement of the strategic bombing campaign was the destruction of the German oil supply. Oil was essential for U-boats and tanks, while very high quality aviation gasoline was essential for piston planes.[5] Germany had few wells, and depended on imports from Russia (before 1941) and Nazi ally Romania, and on synthetic oil plants that used chemical processes to turn coal into oil. Heedless of the risk of Allied bombing, the Germans had carelessly concentrated 80% of synthetic oil production in just 20 plants. These became a top priority for the AAF and RAF in 1944, and were targets for 210,000 tons of bombs. The oil plants were very hard to hit, but also hard to repair. As graph #1 shows, the bombings dried up the oil supply in the summer of 1944. An extreme oil emergency followed, which grew worse month by month.

The third notable achievement of the bombing campaign was the degradation of the German transportation system--its railroads and canals (there was little truck traffic.) In the two months before and after D-Day the American Liberators (B-24), Flying Fortresses and British Lancasters hammered away at the French railroad system. Underground Resistance fighters sabotaged some 350 locomotives and 15,000 freight cars every month. Critical bridges and tunnels were cut by bombing or sabotage. Berlin responded by sending in 60,000 German railway workers, but even they took two or three days to reopen a line after heavy raids on switching yards. The system deteriorated quickly, and it proved incapable of carrying reinforcements and supplies to oppose the Normandy invasion. To that extent the assignment of strategic bombers to the tactical job of interdiction was successful. When Bomber Command hit German cities, it inevitably hit some railroad yards. The AAF made railroad yards a high priority, and gave considerable attention as well to bridges, moving trains, ferries, and other choke points. The "transportation policy" of targeting the railroad system came in for intense debate among Allied strategists. It was argued that enemy had the densest and best operated railway system in the world, and one with a great deal of slack. The Nazis systematically looted rolling stock from conquered nations, so they always had plenty of locomotives and freight cars. Furthermore, most traffic was "civilian," and urgent troop train traffic would always get through. The critics exaggerated the resilience of the German system. As wave after wave of bombers blasted away, repairs took longer and longer. Delays became longer and more frustrating. Yes, the troop trains usually got through, but the "civilian" traffic that did not get through comprised food, uniforms, medical equipment, horses, fodder, tanks, fuel, howitzers, flak shells and machine guns for the front lines, and coal, steel, spare parts, subassemblies, and critical components for munitions factories. By January, 1945, the transportation system was cracking in dozens of places, and front-line units had more luck trying to capture Allied weapons than waiting for fresh supplies of their own.

References

- ↑ Webster & Franklin, 4:24

- ↑ see Isaacson and Thomas, Wise Men p. 206

- ↑ See [http://www.maxwell.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/readings/awpd-1-jfacc/awpdcovr.htm "AWPD-1 The Process" (1996)

- ↑ .. Werrell 707

- ↑ Jet planes ran on cheap kerosene, and rockets used plain alcohol; the railroad system used coal, which was in abundant supply.