User:Ryan Cooley/MPEG1

MPEG-1 was an early standard for lossy compression of video and audio. It was designed to compress VHS-quality raw digital video and CD audio from about 43 Mbit/s down to 1.5 Mbit/s (almost 30:1)[1] without obvious quality loss, making Video CDs and Digital Audio Broadcasting possible.[2] [3]

Today, MPEG-1 has become the most widely compatible lossy audio/video format in the world, and is used in a large number of products and technologies. Perhaps the best-known part of the MPEG-1 standard is the MP3 audio format it introduced.

Despite it's age, MPEG-1 is not necessarily obsolete or substantially inferior to newer technologies. According to Leonardo Chiariglione (co-founder of MPEG): "the idea that compression technology keeps on improving is a myth."[4]

The MPEG-1 standard is published as ISO/IEC-11172.

History

Modeled on the successful collaborative approach and the compression technologies developed by the Joint Photographic Experts Group and CCITT's Experts Group on Telephony (creators of the JPEG image compression standard and the H.261 standard for video conferencing respectively) the Moving Picture Experts Group (MPEG) working group was established in January 1988. MPEG was formed to address the need for standard video and audio encoding formats, and build on H.261 to get better quality through the use of more complex (non-real time) encoding methods.[2] [5]

Development of the MPEG-1 standard began in May 1988. 14 video and 14 audio codec proposals were submitted by individual companies and institutions for evaluation. The codecs were extensively tested for computational complexity and subjective (human perceived) quality, at data rates of 1.5 Mbit/s. This specific bitrate was chosen for transmission over T-1/E-1 lines and as the approximate data rate of audio CDs.[4] The codecs that excelled in this testing were utilized as the basis for the standard and refined further, with additional features and other improvements being incorporated in the process.[6]

After 20 meetings of the full group in various cities around the world, and 4 1/2 years of development and testing, the final standard was approved in early November 1992 and published a few months later.[7] The completion date for the MPEG-1 standard, as commonly reported, varies greatly because a largely complete draft standard was produced in September 1990, and from that point on, only minor changes were introduced.[2] In July 1990, before the first draft of the MPEG-1 standard had even been written, work began on a second standard, MPEG-2,[8] intended to extend MPEG-1 technology to provide full broadcast-quality video (as per CCIR 601) at high bitrates (3 - 15 Mbit/s), and support for interlaced video.[9] Due in part to the similarity between the two codecs, the MPEG-2 standard includes full backwards compatibility with MPEG-1 video, so any MPEG-2 decoder can play MPEG-1 videos.[10]

Notably, the MPEG-1 standard very strictly defines the bitstream, and decoder function, but does not define how MPEG-1 encoding is to be performed (although they did provide a reference implementation in ISO/IEC-11172-5). This means that MPEG-1 coding efficiency can drastically vary depending on the encoder used, and generally means that newer encoders perform significantly better than their predecessors.

Applications

- Most computer software for video playback includes MPEG-1 decoding, in addition to any other supported formats.

- MPEG-1 video and Layer I/II audio can be implemented without payment of license fees.[11] [12] [13] [14] Due to its age, many of the patents on the technology have expired.

- The popularity of MP3 audio has established a massive installed base of hardware that can playback MPEG-1 audio (all 3 layers).

- Millions of portable digital audio players can playback MPEG-1 audio.

- The widespread popularity of MPEG-2 with broadcasters means MPEG-1 is playable by most digital cable/satellite set-top boxes, and digital disc and tape players, due to backwards compatibility.

- MPEG-1 is the exclusive video and audio format used on Video CD (VCD), the first consumer digital video format, and still a very popular format around the world.

- The Super Video CD standard, based on VCD, uses MPEG-1 audio exclusively, as well as MPEG-2 video.

- DVD-Video uses MPEG-2 video primarily, but MPEG-1 support is explicitly defined in the standard.

- The DVD Video standard originally required MPEG-1 Layer II audio for PAL countries, but was changed to allow AC-3/Dolby Digital-only discs. MPEG-1 Layer II audio is still allowed on DVDs, although newer extensions to the format like MPEG Multichannel and variable bitrate (VBR), are rarely supported.

- Most DVD players also support Video CD and MP3 CD playback, which use MPEG-1.

- The international Digital Video Broadcasting (DVB) standard primarily uses MPEG-1 Layer II audio, as well as MPEG-2 video.

- The international Digital Audio Broadcasting (DAB) standard uses MPEG-1 Layer II audio exclusively, due to error resilience and low computational complexity of decoding.

Systems

Part 1 of the MPEG-1 standard covers systems, which is the logical layout of the encoded audio, video, and other bitstream data, and is defined in ISO/IEC-11172-3.

This structure is better known as a program stream: "The MPEG-1 Systems design is essentially identical to the MPEG-2 Program Stream structure."[15] This terminology will be used here.

Elementary Streams

Elementary streams (ES) are the raw bitstreams of MPEG-1 audio and video output by an encoder. These files can be distributed on their own, such as with MP3 files.

Additionally, elementary streams can be made more robust by packetizing them, ie. dividing them into independent chunks, and adding a cyclic redundancy check (CRC) checksum to each segment, for error detection. This is the Packetized Elementary Stream (PES) structure.

Program Streams

Program Streams (PS) are concerned with combining multiple packetized elementary streams (usually just one audio and video PES) into a single stream, ensuring simultaneous delivery, and maintaining synchronization between them. The PS structure may be known as a container format or a multiplex.

System Clock Reference (SCR) is a timing value stored in the a 33-bit header of each ES, at a frequency/precision of 90kHz, with an extra 9-bit extension that stores a precision of 27MHz.[16] [17] These are inserted by the encoder, derived from the system time clock (STC). Simultaneously encoded audio and video streams will not have identical SCR values, however, due to buffering, encoding, multiplexing, jitter, and other delay.

Program time stamps (PTS) exist in PS to correct this disparity in audio and video (time-base correction). 90KHz PTS values in the header tell the decoder which video SCR values match which audio SCR values.[16] PTS determines when to display a portion of a MPEG program, and is also used by the decoder to decide when buffered data can be discarded from the data buffer. [18] Either video or audio will be delayed by the decoder until the corresponding segment of the other (with the matching PTS value) arrives and can be decoded.

PTS handling can be problematic because multiple program streams can be joined (concatenated) sequentially, which will cause PTS values in the middle of the video to reset to zero, and begin incrementing again. Such wraparound disparities must be handled by the decoder.

Display Time Stamps (DTS), additionally, are required because of B-frames. With B-frames in the video stream, adjacent frames have to be encoded and decoded out-of-order (reordered). DTS is quite similar to PTS, but instead of just handling a sequential stream of frames, it contains the proper time-stamps to tell the decoder when to skip ahead and decode the next B-frame, delaying the display of the current P- or I- frame. Without B-frames in the video, PTS and DTS are identical.[19]

Multiplexing

To generate the PS, the multiplexer will interleave the two or more packetized elementary streams. This is done so the packets of the simultaneous streams will arrive at the decoder at about the same time. This is a case of time-division multiplexing.

Determining how much data from each stream should be in each interleaved segment (the size of the interleave) is complicated, and an important requirement. Improper interleaving will result in buffer underflows or overflows, as the receiver gets more of one stream than it can store (eg. audio), before it gets enough data to decode the other simultaneous stream (eg. video). The MPEG Video Buffer Verifier (VBV) assists in determining if a multiplexed PS can be decoded by a device with a specified data throughput rate and buffer size.[20] This offers feedback to the muxer and the encoder, so that they can change the mux size or adjust bitrates as needed for compliance.

The PS, additionally, stores aspect ratio information which tells the decoder how much to stretch the height or width of a video when displaying it. This is important because different display devices (such as computer monitors and televisions) have different pixel height/width, which will result in video encoded for one appearing "squished" when played on the other, unless the aspect ratio information in the PS is used to compensate.

Video =

Part 2 of the MPEG-1 standard covers video and is defined in ISO/IEC-11172-2.

Color Space

Before encoding video to MPEG-1 the color-space is transformed to Y'CbCr (Y'=Luma, Cb=Chroma Blue, Cr=Chroma Red). Luma (brightness, resolution) is stored separately from chroma (color, hue, phase) and even further separated into red and blue components. The chroma is also subsampled to 4:2:0, meaning it is decimated by half vertically and half horizontally, to just one quarter the resolution of the video.

Because the human eye is much less sensitive to small changes in color than in brightness, chroma subsampling is a very effective way to reduce the amount of video data that needs to be compressed. On videos with fine details (high spatial complexity) this can manifest as chroma aliasing artifacts. Compared to other digital compression artifacts, this issue seems to be very rarely a source of annoyance.

Because of subsampling, Y'CbCr video must always be stored using even dimensions (divisible by 2), otherwise chroma mismatch ("ghosts") will occur, and it will appear as if the color is ahead of, or behind the rest of the video, much like a shadow.

Note: Y'CbCr is often inaccurately called YUV which is actually only used in the domain of analog video signals. Similarly, the term luminance is often used instead of the more accurate term: luma.

Resolution

MPEG-1 supports resolutions up to 4095×4095, and bitrates up to 100 Mbit/sec.[5]

MPEG-1 videos are most commonly seen using Source Input Format (SIF) resolution: 352x240, 352x288, or 320x240. These low resolutions, combined with a bitrate less than 1.5 Mbit/s, makes up what is known as a constrained parameters bitstream (CPB). This is the minimum video specifications any decoder should be able to handle, to be considered MPEG-1 compliant. This was selected to provide a good balance between quality and performance, allowing the use of reasonably inexpensive hardware of the time.[2] [5]

Frame/Picture/Block Types

MPEG-1 has several frame and picture types that serve different purposes. The most important, yet simplest are I-frames.

I-Frames

I-frame is an abbreviation for Intra-frame, so-called because they can be decoded independently of any other frames. They may also be known as I-pictures, or keyframes due to their somewhat similar function to the key frames used in animation. I-frames can be considered effectively identical to baseline JPEG images.[5]

High-speed seeking through an MPEG-1 video is only possible to the nearest I-frame. When cutting a video it is not possible to start playback of a segment of video before the first I-frame in the segment (at least not without computationally-intensive re-encoding). For this reason, I-frame only MPEG videos are used in editing applications.

I-frame only compression is very fast, but produces very large file sizes: a factor of 3× (or more) larger than normally encoded MPEG-1 video.[2] I-frame only MPEG-1 video is very similar to MJPEG video, so much so that very high-speed and nearly lossless (except rounding errors) conversion can be made from one format to the other, provided a couple restrictions (color space and quantizer table) are followed in the creation of the bitstream.[21]

The length between I-frames is known as the group of pictures (GOP) size. MPEG-1 most commonly uses a GOP size of 15-18. ie. 1 I-frame for every 14-17 non-I-frames (some combination of P- and B- frames). With more intelligent encoders, GOP size is dynamically chosen, up to some pre-selected maximum limit.[5]

Limits are placed on the maximum number of frames between I-frames due to decoding complexing, decoder buffer size, seeking ability, and and accumulation of IDCT errors in low-precision implementations, common in hardware decoders.

P-frames

P-frame is an abbreviation for Predicted-frame. They may also be known as forward-predicted frames, or intra-frames (B-frames are also intra-frames).

P-frames exist to improve compression by exploiting the temporal (over time) redundancy in a video. P-frames store only the difference in image from the frame (either an I-frame or P-frame) immediately preceding it (this reference frame is also called the anchor frame). This is called conditional replenishment.

The difference between a P-frame and its anchor frame is calculated using motion vectors on each macroblock of the frame (see below). Motion vector data will be embedded in the P-frame for use by the decoder.

If a reasonable match is found, the block from the previous frame is used, and any prediction error (difference between the predicted block and the actual video) is encoded and stored in the P-frame. If a reasonably close match from the previous frame for a block cannot be found, the block will be intra-coded (storing the block as an image, in full). A P-frame can contain any number of intra-coded blocks, in addition to any forward-predicted blocks.[22]

If a video drastically changes from one frame to the next (such as a scene change), it can be more efficient to encode it as an I-frame.

B-frames

B-frame stands for bidirectional-frame. They may also be known as backwards-predicted frames or B-pictures. B-frames are quite similar to P-frames, except they can make predictions using either, or both of, the previous and future frames (ie. two anchor frames).

It is therefore necessary for the player to first decode the next I- or P- anchor frame sequentially after the B-frame, before the B-frame can be decoded and displayed. This makes B-frames very computationally complex, requires larger data buffers, and causes an increased delay on both decoding and during encoding. This also necessitates the display time stamps (DTS) feature in the container/system stream (see above). As such, B-frames have long been subject of much controversy, they are often avoided in videos, and have limited support in decoder hardware.

No other frames are predicted from a B-frame. Because of this, a very low bitrate B-frame can be inserted, where needed, to help control the bitrate. If this was done with a P-frame, future P-frames would be predicted from it and will lower the quality of the entire sequence. However, similarly, the future P-frame must still encode all the changes between it and the previous I- or P- anchor frame a second time, in addition to much of the changes being coded in the B-frame. B-frames can also be beneficial in videos where the background behind an object is being revealed over several frames, or in fading transitions, such as scene changes.[2]

A B-frame can contain any number of intra-coded blocks and forward-predicted blocks, in addition to backwards-predicted, or bidirectionally predicted blocks.[5] [22]

D-frames

MPEG-1 has a unique frame type not found in later video standards. D-frames or DC-pictures are independent images (intra-frames) that have been encoded DC-only (AC coefficients are removed—see DCT below) and hence are very low quality. D-frames are never referenced by I-, P- or B- frames. D-frames are only used for fast previews of video, for instance when seeking through a video at high speed.[2]

Given moderately higher-performance decoding equipment, this feature can be approximated by decoding I-frames instead. This provides higher quality previews, and without the need for D-frames taking up space in the stream, yet not contributing to overall quality.

Macroblocks

MPEG-1 operates on video in a series of 8x8 blocks for quantization. However, because chroma (color) is subsampled by a factor of 4, each pair of (red and blue) chroma blocks corresponds to 4 different luma blocks. This set of 6 blocks, with a resolution of 16x16, is called a macroblock.

A macroblock is the smallest independent unit of (color) video. Motion vectors (see below) operate solely at the macroblock level.

If the height and/or width of the video are not exact multiples of 16, a full row of macroblocks must still be encoded (though not displayed) to store the remainder of the picture. This wastes a significant amount of data in the bitstream, and is to be strictly avoided.

Decoders may also improperly handle videos with partial macroblocks, causing chroma to be displayed several pixels offset from where it should be in the picture. A chroma mismatch.

Motion Vectors

To decrease the amount of spatial redundancy in a video, only blocks that change are updated, (up to the maximum GOP size). This is known as conditional replenishment. However, this is not very effective by itself. Movement of the objects, and/or the camera, may result in large portions of the frame needing to be updated, even though only the position of the previously encoded objects has changed.

Though motion estimation the encoder compensates for this movement by looking in a radius patern around the anchor frame (previous I- or P- frame), up to a predefined encoder limit. This will help find areas elsewhere in the anchor frame that may match the current macroblock. If so, only the direction and distance from the previous macroblock to the current block need to be encoded into the (P- or B-) frame. A predicted macroblock rarely exactly matches the current picture, however, and any differences between the estimation and the real frame must be seperately encoded in the P- or B- frame. This is called the prediction error.

Since motion vectors for neighboring macroblocks are likely to have very similar motion vectors, this information can be compressed quite effectively with DPCM so only the (smaller) amount of difference between each needs to be stored in the bitstream.

For playback, the decoder will use this motion vector data to perform motion compensation to display each predicted macroblock' in the appropriate position. The (stored) prediction error data will also be decoded, and applied to the predicted macroblocks.

Motion vectors record distance based on the number of pixels (pels). MPEG-1 video uses a motion vector precision of one half of one pixel (half-pel). The finer the precision of the motion vectors, the more accurate the match is likely to be, and the more efficient the compression.

P-frames have 1 motion vector per macroblock, while B-frames can use 2 (one from the previous anchor frame, one from the future anchor frame).[22]

Partial macroblocks will cause havoc with motion prediction/vectors, and lower quality or increase the bitrate significantly. This is also true if black bars/borders encoded into the video do not fall exactly on a macroblock boundary, or if macroblocks (around the edge of a video) contain significant random noise, or some other transition to a static color.

An insufficient bitrate to store the full prediction error is a major cause of MPEG-1 video artifacts. Motion vectors are the cause of artifacts that "move" around the screen.

DCT

Each 8x8 block is (centered around 0 by subtract by half the number of possible values, then...) encoded using the Forward Discrete Cosine Transform (FDCT). This process by itself is practically lossless (there are some rounding errors), and is reversed by the Inverse DCT (IDCT) upon playback to produce the original values.

The FDCT process converts the 64 uncompressed pixel values (brightness) into 64 different frequency values. One (large) value that is the average of the entire 8x8 block (the DC coefficient) and 63 smaller, positive or negative values (the AC coefficients), that are relative to the value of the DC coefficient.

An example FDCT encoded 8x8 block:

The DC coefficient remains mostly consistent from one block to the next, and can be compressed quite effectively with DPCM so only the amount of difference between each DC value needs to be stored. Additionally, this DCT frequency conversion is necessary for quantization (see below).

Quantization

Quantization (of digital data) is, essentially, the process of reducing the accuracy of a signal, by dividing it into some larger step size (eg. finding the nearest multiple, and discarding the remainder/modulus).

The frame-level quantizer is a number from 1 to 31 (although encoders will often omit/disable some of the extreme values) which determines how much information will be removed from a given frame. The frame-level quantizer is either dynamically selected by the encoder to maintain a certain user specified bitrate, or (much less commonly) directly specified by the user.

Contrary to popular belief, a fixed frame-level quantizer (set by the user) does not deliver a constant level of quality. Instead, it is an arbitrary metric, that will provide a somewhat varying level of quality depending on the contents of each frame. Given two files of identical sizes, the one encoded with a fixed bitrate should look better than the one encoded with a fixed quantizer. Constant quantizer encoding can be used, however, to determine the minimum and maximum bitrates possible for encoding a given video.

A quantization table is a string of 64-numbers (0-255) that tells the encoder how relatively important or unimportant each piece of visual information is. Each number in the table corresponds to a certain frequency component of the video image.

An example quantization matrix:

Quantization is performed by taking each of the 64 frequency values of the DCT block, dividing them by the frame-level quantizer, then dividing them by their corresponding values in the quantization table. Finally, the result is rounded down. This reduces or completely eliminates the information in some frequency components of the video. Typically, high frequency information is less visually important, and so high frequencies are much more strongly quantized (ie. drastically reduced or entirely removed). MPEG-1 actually uses two separate quantization tables, one for intra-blocks (I-blocks) and one for inter-block (P- and B- blocks) so quantization of different block types can be done independently, and more effectively.[2]

This quantization process usually reduces a significant number of the AC coefficients to zero, (known as sparse data) which can then be more efficiently compressed by entropy coding (lossless compression) in the next step.

An example quantized DCT block:

Quantization eliminates a large amount of data, and is the main lossy processing step in MPEG-1 video encoding. This is also the primary source of most MPEG-1 video compression artifacts, like blockiness, color banding, noise, ringing, discoloration, et al. This happens when video is encoded with an insufficient bitrate, and the encoder is therefore forced to use high frame-level quantizers (strong quantization) through much of the video.

Entropy Coding

Several steps in the encoding of MPEG-1 video are lossless, meaning they will be reversed upon decoding, to produce exactly the same (original) values. Since these lossless data compression steps don't add noise into or otherwise change the contents (unlike quantization), it is sometimes referred to as noiseless coding.[23] Since lossless compression aims to remove as much redundancy as possible, it is known as entropy coding in information theory.

RLE

Run-length encoding (RLE) is a very simple method of compressing repetition. A sequential string of characters, no matter how long, can be replaced with a few bytes, noting the value that repeats, and how many times. For example, if someone is to say "five nines", you would know they mean the number: 99999.

RLE is particularly effective after quantization, as a significant number of the AC coefficients are now zero (called sparse data), and can be represented with just a couple bytes, in a special 2-dimensional Huffman table that codes the run-length and the run-ending character.

Huffman Coding

The data is then analyzed to find strings that repeat often. Those strings are then put into a special Huffman table, with the most frequently repeating data assigned the shortest code. This keeps the data as small as possible with this form of compression.[23]

Once the table is constructed, those strings in the data are replaced with their (much smaller) codes, which references the appropriate entry in the table. This is the final step in the video encoding process, so the result of Huffman coding is known as the MPEG-1 video "bitstream."

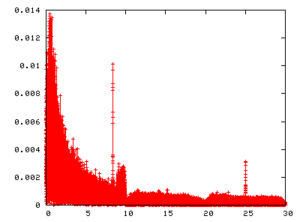

zigzag CBR/VBR Spacial Complexity* Temporal Complexity

Audio

Part 3 of the MPEG-1 standard covers audio and is defined in ISO/IEC-11172-3.

MPEG-1 audio utilizes psychoacoustics to significantly reduce the data rate required by an audio stream. It reduces or completely discards certain parts of the audio that the human ear can't hear, either because they are in frequencies where the ear has limited sensitivity, or are masked by other, typically louder, sounds.

Channel Encoding:

- Mono

- Joint Stereo (intensity encoded)

- Stereo

- Dual (two uncorrelated mono channels)

- Sampling rates: 32000, 44100, and 48000 Hz

- Bitrates: 32, 48, 56, 64, 80, 96, 112, 128, 160, 192, 224, 256, 320 and 384 kbit/s

MPEG-1 Audio is divide into 3 layers. Each higher layer is more computationally complex, and more efficient than the previous. The layers are also backwards compatible, so a Layer II decoder can also play Layer I audio, but NOT Layer III audio.

Layer I

MPEG-1 Layer I is nothing more than a simplified version of Layer II.[6] Layer I uses a 384-sample frame size, for very low-delay, and finer resolution, for applications like teleconferencing, studio editing, etc. It has lower complexity than Layer II to facilitate real-time encoding on the hardware available circa 1990[23]. With the substantial performance improvements in digital processing since, Layer I quickly became unnecessary and obsolete.

Layer I saw limited adoption in it's time, and most notably was used on the defunct Philips Digital Compact Cassette at 384 kbps.

Layer I audio files typically use the extension .mp1 or sometimes .m1a

Layer II

MPEG-1 Layer II (aka. MP2, often incorrectly called Musicam) is a time-domain encoder. It uses a low-delay 32 sub-band polyphased filter bank for time-frequency mapping; having overlapping ranges (ie. polyphased) to prevent aliasing. The psychoacoustic model is based on auditory masking / simultaneous masking effects and the absolute threshold of hearing (ATH) / global masking threshold. The size of an MP2 frame is fixed at 1152-samples (coefficients).

Time domain refers to how quantization is performed: on short, discrete samples/chunks of the audio waveform. This offers low-delay as a small number of samples are analyzed before encoding, as opposed to frequency domain encoding (like MP3) which must analyze a large number of samples before it can decide how to transform and output encoded audio. This also offers higher performance on complex, random and transient impulses (such as percussive instruments, and applause), allowing avoidance of artifacts like pre-echo.

Technical Details

The 32 sub-band filter bank returns 32 amplitude coefficients, one for each equal-sized frequency band/segment of the audio, which is about 700Hz wide. The encoder then utilizes the psychoacoustic model to determine which sub-band contains audible information that is less important, and so, where quantization will be in-audible, or at least much less noticeable (higher masking threshold).

The psychoacoustic model is applied using a 1024-point Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). 64 of the 1152 samples are ignored at each end of the frequency range (discarded as presumably insignificant) for this analysis. The psychoacoustic model determines which sub-bands contribute more to the masking threshold, and the available bits are assigned to each sub-band accordingly.

Typically, sub-bands are less important if they contain quieter sounds (smaller coefficient) than a neighboring (ie. similar frequency) sub-band with louder sounds (larger coefficient). Also, sub-bands with "noise" components are typically more important than those with "tonal" components. The less significant sub-bands are then reduced in accuracy by, basically, compressing the frequency range/amplitude, (raising the noise floor), and computing an amplification factor to re-expand it to the proper frequency range for playback/decoding.[24] [25]

Additionally, Layer II can use intensity stereo coding. This means that both channels are down-mixed into one single (mono) channel, but the ("side channel") information on the relative intensity (volume, amplitude) of each channel is preserved and encoded into the bitstream separately. On playback, the single channel is played through left and right speakers, with the intensity information applied to each channel to give the illusion of stereo sound. This perceptual trick is known as stereo irrelevancy. This can allow further reduction of the audio bitrate without much perceivable loss of fidelity, but is generally not used with higher bitrates as it does not provide high quality (transparent) audio.[23]

History

MPEG-1 Layer II was derived from the MUSICAM audio codec (developed in part by Philips-needs ref). Most key features were directly inherited, including the filter bank, time-domain processing, frame sizes, etc. However, improvements were made, and the actual MUSICAM algorithm was not used in the final Layer II standard. The widespread usage of the term MUSICAM to refer to Layer II is entirely incorrect and discouraged for both technical and legal reasons.[26]

Quality

Subjective audio testing by experts, in the most critical conditions ever implemented, has shown MP2 to offer transparent audio compression at 256kbps for 16-bit 44.1khz CD audio.[1] That (approximately) 1:6 compression ratio for CD audio is particularly impressive since it is quite close to the estimated theoretical upper limit of perceptual entropy, at just over 1:8.[27] [28] Achieving much higher compression is simply not possible without discarding some perceptible information.

Despite some 20 years of progress in the field of digital audio coding, MP2 remains the preeminent lossy audio coding standard due to its especially high audio coding performances on highly critical audio material such as castanet, symphonic orchestra, male and female voices and particularly complex and high energy transients (impulses) like percussive sounds: triangle, glockenspiel and audience applause. More recent testing has shown that MPEG Multichannel (based on Layer II), despite being compromised by a significantly inferior matrixed mode, rates just slightly lower than much more recent audio codecs, such as Dolby Digital AC-3 and Advanced Audio Coding (AAC) (mostly within the margin of error, actually—and still superior in some cases, namely audience applause).[29] [30]

This is one reason that Layer II audio continues to be used extensively. Layer II's especially high quality, low decoder performance requirements, and tolerance of errors also helps makes it a popular choice for applications like digital audio broadcasting (DAB).

Layer II audio files typically use the extension .mp2 or sometimes .m2a

Layer III/MP3

MP3 is a frequency domain transform encoder that utilizes a dynamic psychoacoustic model.

Optimum Coding in the Frequency Domain (OCF) the Ph.D thesis by Karlheinz Brandenburg was the primary basis for the Adaptive Spectral Perceptual Entropy Coding (ASPEC) codec developed by Fraunhofer. ASPEC was adapted to fit in with the Layer II model, to become Layer III/MP3.

Even though it utilizes some of the lower layer functions, MP3 is quite different from Layer II.

In addition to Layer II intensity encoded joint stereo, MP3 can alternatively use mid/side joint stereo. With mid/side stereo, a small range of certain key frequencies is stored separately for each channel, in addition to intensity information. This provides higher fidelity joint stereo encoding.

The Layer II 1024 point (FFT) analysis window for spectral estimation is too small to cover all 1152 samples, so MP3 utilize two sequential passes.

MP3 does not benefit from the 32 sub-band filter bank, instead just using an 18-point MDCT transformation to split the data into 576 frequency components, and processing it in the frequency domain. This is particularly important because some critical bands ("barks") are quite narrow. This extra granularity allows MP3 to much more accurately apply its psychoacoustic model than Layer II (with just 32 sub-bands) and providing much better low-bitrate performance.

MP3 works on 1152 samples like Layer II, but needs to take multiple samples before MDCT processing can be effective. It also outputs in larger chunks and spreads the output over a varying number of several Layer I/II-sized output frames. This has made MP3 considered unsuitable for studio applications where editing or other processing needs to take place, and broadcasting, as small bit errors will cascade though the audio over a much longer time period.

Unlike Layers I/II, MP3 uses Huffman coding (after perceptual) to further reduce the bitrate, without any further quality loss. This however also makes MP3 even more significantly affected by small errors.

The frequency domain (MDCT) design of MP3 imposes some limitations as well. It causes a factor of 12 - 36 times worse temporal resolution than Layer II, which causes artifacts due to transient sounds like percussive events, with artifacts spread over a larger window. This results in audible smearing and pre-echo.[31] And yet in choosing a fairly small window size trying to make MP3's temporal response adequate to avoid serious artifacts, it uses a smaller window size, and is much less efficient in (regular) frequency domain compression, and requiring a higher bitrate.

Being forced to use this type of hybrid time domain (filter bank) and frequency domain (MDCT) model wastes processing time and also compromises MP3 quality by introducing additional aliasing artifacts. MP3 has an aliasing compensation stage specifically to mask this problem, but instead producing frequency domain energy which is pushed to the top of the frequency range, and results in noise/distortion.

These issues prevent MP3 from providing transparent quality at any bitrate, and thereby making Layer II sound quality superior to MP3 audio at high bitrates.

Layer III audio files use the extension .mp3

No scale factor band for frequencies above 15.5/15.8 kHz"? ASPEC (Fraunhofer)* "aliasing compensation"?* need more details! "If there is a transient, 192 samples are taken instead of 576 to limit the temporal spread of quantization noise" ringing CBR/VBR

MPEG-2 Audio Extensions

The MPEG-2 standard includes several extensions to MPEG-1 Audio. MPEG-2 Audio is defined in ISO/IEC-13818-3

VBR audio encoding

MPEG Multichannel ISO/IEC 14496-3. Backward compatible 5.1-channel surround sound.[10]

Bitrates: 8, 16, 24, 40, 48, and 144 kbit/s

Sampling rates: 16000, 22050, and 24000 Hz

These sampling rates are exactly half that of those originally defined for MPEG-1 Audio. They were introduced to maintain higher quality sound when encoding audio at lower-bitrates.[10] The lower bitrates were introduced because tests showed that MPEG-1 Audio would provide higher quality than any existing (circa 1994) low-bitrate (ie. speech) audio codecs.[32]

Conformance Testing

Part 4 of the MPEG-1 standard covers conformance testing, and is defined in ISO/IEC-11172-4.

Conformance: Procedures for testing conformance.

Reference Software

Part 5 of the MPEG-1 standard includes reference software, and is defined in ISO/IEC-11172-5.

Simulation: Reference software.

Includes ISO Dist10 audio encoder code LAME and TooLAME was based upon.

See Also

- MPEG The Moving Picture Experts Group, developers of the MPEG-1 standard

- MP3 More details on MPEG-1 Layer III audio

- MPEG Multichannel Backwards compatible 5.1 channel surround sound extension to Layer II audio

- MPEG-2 The direct successor to the MPEG-1 standard.

- Implementations

- Libavcodec includes MPEG-1 video/audio encoders and decoders

- Mjpegtools MPEG-1/2 video/audio encoders

- TooLAME A high quality MPEG-1 Layer II audio encoder.

- LAME A high quality MP3 (Layer III) encoder.

- Musepack A format originally based on MPEG-1 Layer II audio, but now incompatible.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Gadegast, Frank (November 09, 1996), MPEG-FAQ: multimedia compression, faqs.org. Retrieved on 2008-04-09

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Le Gall, Didier (April, 1991), MPEG: a video compression standard for multimedia applications, Communications of the ACM. Retrieved on 2008-04-09

- ↑ Chiariglione, Leonardo (October 21, 1989), Kurihama 89 press release, ISO/IEC. Retrieved on 2008-04-09

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Chiariglione, Leonardo (March, 2001), Open source in MPEG, Linux Journal. Retrieved on 2008-04-09

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Fogg, Chad (April 2, 1996), MPEG-2 FAQ, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved on 2008-04-09

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Chiariglione, Leonardo; Didier Le Gall & Hans-Georg Musmann et al. (September, 1990), Press Release - Status report of ISO MPEG, ISO/IEC. Retrieved on 2008-04-09

- ↑ Meetings, ISO/IEC. Retrieved on 2008-04-09

- ↑ Achievements, ISO/IEC. Retrieved on 2008-04-03

- ↑ Chiariglione, Leonardo (November 06, 1992), MPEG Press Release, London, 6 November 1992, ISO/IEC. Retrieved on 2008-04-09

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Wallace, Greg (April 02, 1993), Press Release, ISO/IEC. Retrieved on 2008-04-09

- ↑ ODS Receives DVD Royalty Clarification by German Court, emedialive.com, December 08, 2006. Retrieved on 2008-04-09

- ↑ Ozer, Jan (October 12, 2001), Choosing the Optimal Video Resolution: The MPEG-2 Player Market, extremetech.com. Retrieved on 2008-04-09

- ↑ Comparison between MPEG 1 & 2, snazzizone.com. Retrieved on 2008-04-09

- ↑ MPEG 1 And 2 Compared, Pure Motion Ltd., 2003. Retrieved on 2008-04-09

- ↑ Chiariglione, Leonardo, MPEG-1 Systems, ISO/IEC. Retrieved on 2008-04-09

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Pack Header. Retrieved on 2008-04-07

- ↑ Fimoff, Mark & Wayne E. Bretl (December 1, 1999), MPEG2 Tutorial. Retrieved on 2008-04-09

- ↑ Fimoff, Mark & Wayne E. Bretl (December 1, 1999), MPEG2 Tutorial. Retrieved on 2008-04-09

- ↑ Fimoff, Mark & Wayne E. Bretl (December 1, 1999), MPEG2 Tutorial. Retrieved on 2008-04-09

- ↑ Fimoff, Mark & Wayne E. Bretl (December 1, 1999), MPEG2 Tutorial. Retrieved on 2008-04-09

- ↑ Acharya, Soam & Brian Smith (1998), Compressed Domain Transcoding of MPEG, Cornell University, IEEE Computer Society, ICMCS, at 3. Retrieved on 2008-04-09 - (Requires clever reading: says quantization tables differ, but those are just defaults, and selectable)

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Wee, Susie J.; Bhaskaran Vasudev & Sam Liu (March 13, 1997), Transcoding MPEG Video Streams in the Compressed Domain, HP. Retrieved on 2008-04-09

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Grill, B. & S. Quackenbush (October, 2005), MPEG-1 Audio, ISO/IEC. Retrieved on 2008-04-03

- ↑ Smith, Brian (1996), A Survey of Compressed Domain Processing Techniques, Cornell University, at 7. Retrieved on 2008-04-09

- ↑ Humfrey, Nicholas (Apr 15, 2005), Psychoacoustic Models in TwoLAME, twolame.org. Retrieved on 2008-04-09

- ↑ Thom, D. & H. Purnhagen (October, 1998), MPEG Audio FAQ Version 9, ISO/IEC. Retrieved on 2008-04-09

- ↑ J. Johnston, Estimation of Perceptual Entropy Using Noise Masking Criteria, in Proc. ICASSP-88, pp. 2524-2527, May 1988.

- ↑ J. Johnston, Transform Coding of Audio Signals Using Perceptual Noise Criteria, IEEE Journal Select Areas in Communications, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 314-323, Feb. 1988.

- ↑ Wustenhagen et al, Subjective Listening Test of Multi-channel Audio Codecs, AES 105th Convention Paper 4813, San Francisco 1998

- ↑ B/MAE Project Group (September, 2007), EBU evaluations of multichannel audio codecs, European Broadcasting Union. Retrieved on 2008-04-09

- ↑ Pan, Davis (Summer, 1995), A Tutorial on MPEG/Audio Compression, IEEE Multimedia Journal, at 8. Retrieved on 2008-04-09

- ↑ Chiariglione, Leonardo (November 11, 1994), Press Release, ISO/IEC. Retrieved on 2008-04-09

External Links

- Official Web Page of the Moving Picture Experts Group (MPEG) a working group of ISO/IEC

- MPEG Industry Forum Organization

bn:এমপেগ-১ bs:MPEG-1 ca:MPEG-1 da:MPEG-1 de:MPEG-1 et:MPEG-1 es:MPEG-1 fr:MPEG-1 ko:MPEG-1 it:MPEG-1 ja:MPEG-1 pl:MPEG-1 ru:MPEG-1 sr:МПЕГ-1 fi:MPEG-1 sk:MPEG-1 sv:MPEG-1 tr:MPEG-1 uk:MPEG-1 zh:MPEG-1