Pseudoscience: Difference between revisions

imported>Gareth Leng |

imported>Gareth Leng No edit summary |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

==Introduction== | ==Introduction== | ||

''I feel that what distinguishes the natural scientist from laymen is that we scientists have the most elaborate critical apparatus for testing ideas: we need not persist in error if we are determined not to do so'' (Peter Medawar, "The Philosophy of Karl Popper" 1977) | ''<blockquote>I feel that what distinguishes the natural scientist from laymen is that we scientists have the most elaborate critical apparatus for testing ideas: we need not persist in error if we are determined not to do so'' (Peter Medawar, "The Philosophy of Karl Popper" 1977)</blockquote> | ||

What makes a body of knowledge, methodology, or practice "scientific" varies from field to field, but generally such judgements rest on to what extent "evidence" from "experiments" is important, and how such evidence changes the nature of the current theories. If evidence is important in a field, then it is important that it should be reliably reproducible, so scientists take care to describe their methods precisely, and include careful control experiments to check that their interpretation of a finding is accurate. Things that we believe are true regardless of any evidence are not scientific truths; these things we might sometimes call dogma, or faith, or superstition. Things that we believe because of the evidence of our senses are not scientific truths either, these we might call merely facts, or deductions from facts. "If it walks like a duck and talks like a duck, it's a duck" is not a scientific statement, and it's no more scientific if we make it sound more profound, "If its gait is like that of ''Anatidae'', and it vocalises like ''Anatidae''...". However, a statement like "If it walks like a duck and talks like a duck, it has the genes of a duck" ''is'' a scientific statement, because it seeks to tell us much more than we can see for ourselves; it might be wrong, but it expresses a theory that what makes species distinctive is encoded in genes that are, in some ways, distinctive to that species. It's a bold speculation, but not a random one, it's embedded in a large body of theoretical understanding about how bodies are built, about natural selection, and about molecular biology. It might still be wrong, but it can be tested. | What makes a body of knowledge, methodology, or practice "scientific" varies from field to field, but generally such judgements rest on to what extent "evidence" from "experiments" is important, and how such evidence changes the nature of the current theories. If evidence is important in a field, then it is important that it should be reliably reproducible, so scientists take care to describe their methods precisely, and include careful control experiments to check that their interpretation of a finding is accurate. Things that we believe are true regardless of any evidence are not scientific truths; these things we might sometimes call dogma, or faith, or superstition. Things that we believe because of the evidence of our senses are not scientific truths either, these we might call merely facts, or deductions from facts. "If it walks like a duck and talks like a duck, it's a duck" is not a scientific statement, and it's no more scientific if we make it sound more profound, "If its gait is like that of ''Anatidae'', and it vocalises like ''Anatidae''...". However, a statement like "If it walks like a duck and talks like a duck, it has the genes of a duck" ''is'' a scientific statement, because it seeks to tell us much more than we can see for ourselves; it might be wrong, but it expresses a theory that what makes species distinctive is encoded in genes that are, in some ways, distinctive to that species. It's a bold speculation, but not a random one, it's embedded in a large body of theoretical understanding about how bodies are built, about natural selection, and about molecular biology. It might still be wrong, but it can be tested. | ||

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

==Lessons from the History of Science== | ==Lessons from the History of Science== | ||

''Science is as sorry as you are that this year's science is no more like last year's science than last year's was like the science of twenty years gone by. But science cannot help it. Science is full of change. Science is progressive and eternal. The scientists of twenty years ago laughed at the ignorant men who had groped in the intellectual darkness of twenty years before. We derive pleasure from laughing at them.'' (Mark Twain, "A Brace of Brief Lectures on Science", 1871) | <blockquote>''Science is as sorry as you are that this year's science is no more like last year's science than last year's was like the science of twenty years gone by. But science cannot help it. Science is full of change. Science is progressive and eternal. The scientists of twenty years ago laughed at the ignorant men who had groped in the intellectual darkness of twenty years before. We derive pleasure from laughing at them.'' (Mark Twain, "A Brace of Brief Lectures on Science", 1871)</blockquote> | ||

Popper's vision of the scientific method was soon itself tested by the historian of science [[Thomas Kuhn]]. Kuhn concluded, from analysis of the history of scientific ideas, that science does not progress by a linear accumulation of new knowledge, but undergoes periodic revolutions, which he called "[[paradigm shift]]s", in which the nature of scientific inquiry within a particular field is abruptly transformed. He argued that falsification had played little part in such scientific "revolutions". He concluded that this was because rival paradigms are incommensurable - that it is not possible to understand one paradigm through the conceptual framework and terminology of another.<ref>Kuhn TS (1962) ''[[The Structure of Scientific Revolutions]]'' Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-45808-3</ref> | Popper's vision of the scientific method was soon itself tested by the historian of science [[Thomas Kuhn]]. Kuhn concluded, from analysis of the history of scientific ideas, that science does not progress by a linear accumulation of new knowledge, but undergoes periodic revolutions, which he called "[[paradigm shift]]s", in which the nature of scientific inquiry within a particular field is abruptly transformed. He argued that falsification had played little part in such scientific "revolutions". He concluded that this was because rival paradigms are incommensurable - that it is not possible to understand one paradigm through the conceptual framework and terminology of another.<ref>Kuhn TS (1962) ''[[The Structure of Scientific Revolutions]]'' Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-45808-3</ref> | ||

Revision as of 10:51, 13 November 2006

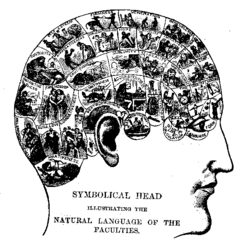

The term pseudoscience which combines the Greek pseudo (false), and the Latin scientia (knowledge), appears to have been used first in 1843 by Magendie, who referred to phrenology as "a pseudo-science of the present day" [1] Among its early uses was in 1844 in the Northern Journal of Medicine to describe "That opposite kind of innovation which pronounces what has been recognized as a branch of science, to have been a pseudo-science, composed merely of so-called facts, connected together by misapprehensions under the disguise of principles".

Introduction

I feel that what distinguishes the natural scientist from laymen is that we scientists have the most elaborate critical apparatus for testing ideas: we need not persist in error if we are determined not to do so (Peter Medawar, "The Philosophy of Karl Popper" 1977)

What makes a body of knowledge, methodology, or practice "scientific" varies from field to field, but generally such judgements rest on to what extent "evidence" from "experiments" is important, and how such evidence changes the nature of the current theories. If evidence is important in a field, then it is important that it should be reliably reproducible, so scientists take care to describe their methods precisely, and include careful control experiments to check that their interpretation of a finding is accurate. Things that we believe are true regardless of any evidence are not scientific truths; these things we might sometimes call dogma, or faith, or superstition. Things that we believe because of the evidence of our senses are not scientific truths either, these we might call merely facts, or deductions from facts. "If it walks like a duck and talks like a duck, it's a duck" is not a scientific statement, and it's no more scientific if we make it sound more profound, "If its gait is like that of Anatidae, and it vocalises like Anatidae...". However, a statement like "If it walks like a duck and talks like a duck, it has the genes of a duck" is a scientific statement, because it seeks to tell us much more than we can see for ourselves; it might be wrong, but it expresses a theory that what makes species distinctive is encoded in genes that are, in some ways, distinctive to that species. It's a bold speculation, but not a random one, it's embedded in a large body of theoretical understanding about how bodies are built, about natural selection, and about molecular biology. It might still be wrong, but it can be tested.

Science has acquired its authority from its successes in changing the world we live in, so when that authority is claimed without being earned, other scientists tend to get upset. When language is used that apes that of conventional scientists but without rigorous respect for its meaning, when claims are built extensively on disputed dogma, when inconvenient evidence is ignored, or when grandiose theories are proposed that yield no non trivial predictions and seem incapable of proper test, then sometimes these things are called "pseudoscience"

However, there is disagreement about whether it is possible to distinguish "science" from "pseudoscience" in a reliable and objective way, and about whether even trying to do so is useful. The philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend argued that all attempts to distinguish science from non-science are flawed. "The idea that science can, and should, be run according to fixed and universal rules, is both unrealistic and pernicious. ... the idea is detrimental to science, for it neglects the complex physical and historical conditions which influence scientific change. It makes our science less adaptable and more dogmatic:"[2] [3] Often the term "pseudoscience" is used simply as a pejorative to express a low opinion of a given field, regardless of any objective measures; thus according to McNally, "The term “pseudoscience” has become little more than an inflammatory buzzword for quickly dismissing one’s opponents in media sound-bites." [4]. Similarly, Larry Laudan has suggested that pseudoscience has no scientific meaning: "If we would stand up and be counted on the side of reason, we ought to drop terms like ‘pseudo-science’ and ‘unscientific’ from our vocabulary; they are just hollow phrases which do only emotive work for us".[5]

The term "pseudoscientific" is sometimes applied by disputants working in the same field to disparage a competing theory or the argument used by a rival, sometimes by commentators from outside a field to disparage a whole field, sometimes to express the opinion that a theory published in a popular book has no academic credibility [6] and sometimes in reference to a theory now discarded. [7] However, for many, some "pseudoscientific" beliefs, such as in astrology, are harmless nonsense; horoscopes are read for fun by many, but taken seriously by few. The National Science Foundation stated that, in the USA, "pseudoscientific" habits and beliefs are common in the USA. [8] Bunge (1999) stated that a 1988 survey showed that 50% of American adults rejected evolution, and 88% believed that astrology was a science. The brights movement, prominently represented by Richard Dawkins, Mario Bunge, Carl Sagan and James Randi, consider that while pseudoscientific beliefs may be held for several reasons, from simple naïveté about the nature of science, to deception for financial or political gain, all such beliefs are harmful.

Defining science by the scientific method

In the mid-20th Century, Karl Popper published "The Logic of Scientific Discovery,"[9] a book that Sir Peter Medawar, a Nobel Laureate in Physiology and Medicine, called "one of the most important documents of the twentieth century". In this book, Popper ............. suggested the criterion of falsifiability to distinguish science from non-science. Theories may be true or false, but if they do not entail predictions that are in principle capable of falsification by experimental tests, then they are devoid of content and hence mere pseudoscience. Popper subdivided non-science into philosophical, mathematical, mythological, religious and/or metaphysical formulations on the one hand, and pseudoscientific formulations on the other, and gave astrology, Marxism, and Freudian psychoanalysis as examples of pseudosciences as being wholly unfalsifiable theories.[10] More recently, Paul Thagard proposed that pseudoscience can be distinguished by its lack of progress, and by the lack of serious attempts by proponents to solve problems with the theory. Mario Bunge has suggested the categories of "belief fields" and "research fields" to help distinguish between science and pseudoscience.

Defining pseudoscience

Science differs from revelation, theology, or spirituality in that it claims to offer insight into the physical world by "scientific" means. Systems of thought that derive from "divine" or "inspired" knowledge are not considered pseudoscience if they do not claim to be scientific. However, a field might plausibly be called pseudoscientific if it is presented as consistent with the accepted norms of scientific research, but demonstrably fails to meet these norms.

The following have been proposed to be indicative of poor scientific reasoning.

- Vague, exaggerated or untestable claims

- Failure to use "operational definitions" (i.e. rigorous descriptions of how measurements are made).

- Failure to use the principle of parsimony, i.e. failing to seek an explanation that requires the fewest possible additional assumptions when other viable explanations are possible (Occam's Razor)

- Use of obscurantist language, and misuse of apparently technical jargon, in an effort to give claims the superficial trappings of science.

- Lack of boundary conditions. Most well-supported scientific theories have clearly specified boundaries under which predictions do or do not apply.

- Assertion of claims that are unfalsififiable, i.e. which cannot be refuted by any conceivable experimental test [11]

- Over-reliance on testimonials and anecdotes. Testimonial and anecdotal evidence can be useful for discovery (hypothesis generation) but should not be used in the context of justification (hypothesis testing). [12]

- Selective use of experimental evidence: presenting data that seem to support claims while suppressing or dismissing data that contradict them.

- Reversed burden of proof. In science, the burden of proof rests on the individual making a claim, not on the critic. "Pseudoscientific" arguments may neglect this principle and demand that skeptics demonstrate beyond reasonable doubt that a claim is false.

- Evasion of peer review before publicizing results ("science by press conference"). [13]

Some proponents of theories that contradict accepted scientific theories avoid the often ego-bruising process of peer review, sometimes on the grounds that peer review is biased against claims that contradict established paradigms, and sometimes on the grounds that assertions cannot be evaluated using standard scientific methods.

- Failure to provide adequate information for other researchers to reproduce claimed results.

- Assertion of claims of secrecy or proprietary knowledge in response to requests for review of data or methodology.

Some of these criticisms has also been levelled to areas regarded as part of conventional science. According to Churchland, "Most terms in theoretical physics, for example, do not enjoy at least some distinct connections with observables, but not of the simple sort that would permit operational definitions in terms of these observables. .. If a restriction in favor of operational definitions were to be followed, therefore, most of theoretical physics would have to be dismissed as meaningless pseudoscience!" [14]

Lack of progress Thagard proposed that a theory or discipline which has pretensions to be scientific can be regarded as pseudoscientific if (and only if): "it has been less progressive than alternative theories over a long period of time, and faces many unsolved problems; but the community of practitioners makes little attempt to develop the theory towards solutions of the problems, shows no concern for attempts to evaluate the theory in relation to others, and is selective in considering confirmations and disconfirmations"

Personalization of issues Authoritarian personality, suppression of dissent, and "groupthink" can enhance the adoption of beliefs that have no rational basis. The group tends to identify their critics as enemies.

- Assertion of claims of a conspiracy by the scientific community to suppress the results.

- Attacking the motives or character of anyone who questions the claims (Ad hominem fallacy).

The demarcation problem, and criticisms of the concept of pseudoscience

Despite broad agreement on the basics of the scientific method, the boundaries between science and non-science continue to be debated. This is the problem of demarcation. The defining feature of science is not experimental success, for, in Rothbart's words, "most clear cases of genuine science have been experimentally falsified". [15] Many disciplines currently thought of as science exhibited at some time in their history, features which are often cited as flaws of scientific method, and many currently accepted scientific theories — including the theory of evolution, plate tectonics, the Big Bang (a term originally chosen by Fred Hoyle to poke fun at the idea), and quantum mechanics — were criticized as being pseudo-scientific when first proposed. In retrospect, it is clear that this was a response to the challenges that they posed to accepted doctrines, and a reflection of the difficulty in gathering evidence for new theories. Further, because of the heterogeneous nature of the scientific enterprise itself, it is difficult to create a set of criteria which can be applied to all disciplines at all times.

Nevertheless, over the years there have been repeated efforts by philosophers of science to propose demarcation criteria. Logical positivism, proposed that only statements about empirical observations are meaningful, thus asserting that all metaphysical statements) are meaningless. Later, Karl Popper attacked logical positivism and introduced his criterion of falsifiability.

Lessons from the History of Science

Science is as sorry as you are that this year's science is no more like last year's science than last year's was like the science of twenty years gone by. But science cannot help it. Science is full of change. Science is progressive and eternal. The scientists of twenty years ago laughed at the ignorant men who had groped in the intellectual darkness of twenty years before. We derive pleasure from laughing at them. (Mark Twain, "A Brace of Brief Lectures on Science", 1871)

Popper's vision of the scientific method was soon itself tested by the historian of science Thomas Kuhn. Kuhn concluded, from analysis of the history of scientific ideas, that science does not progress by a linear accumulation of new knowledge, but undergoes periodic revolutions, which he called "paradigm shifts", in which the nature of scientific inquiry within a particular field is abruptly transformed. He argued that falsification had played little part in such scientific "revolutions". He concluded that this was because rival paradigms are incommensurable - that it is not possible to understand one paradigm through the conceptual framework and terminology of another.[16]

In response, Imre Lakatos proposed that it might instead be possible to distinguish between "progressive" and "degenerative" research programs [17]. Kuhn questioned this, asking "Does a field make progress beecause it is a science, or is it a science because it makes progress?" He also questioned whether scientific revolutions were obviously progressive, noting that Einstein's general theory of relativity is in some respects closer to Aristotle's than either is to Newton's.

Notes

- ↑ Magendie, F (1843) An Elementary Treatise on Human Physiology. 5th Ed. Tr. John Revere. New York, Harper, p 150

- ↑ Feyerabend P (1975) Against Method: Outline of an Anarchistic Theory of Knowledge [1]

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ McNally RJ (2003)Is the pseudoscience concept useful for clinical psychology? SRHMP Vol 2 Number 2 Fall/Winter [3]

- ↑ Laudan L (1996) "The demise of the demarcation problem" in Ruse M But Is It Science?: The Philosophical Question in the Creation/Evolution Controversy pp 337-50

- ↑ [4][5]

- ↑ e.g. phrenology, see [ http://www.theness.com/articles.asp?id=40]

- ↑ [6] National Science Board. 2006. Science and Engineering Indicators 2006 Two volumes. Arlington, VA: National Science Foundation (volume 1, NSB-06-01; NSB 06-01A)

- ↑ Popper KR (1959) The Logic of Scientific Discovery English translation

- ↑ Popper KR (1962) Science, Pseudo-Science, and Falsifiability. Conjectures and Refutations

- ↑ Lakatos I (1970) "Falsification and the Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes" in Lakatos I, Musgrave A (eds) Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge pp 91-195;

- ↑ Bunge M (1983) Demarcating science from pseudoscience Fundamenta Scientiae 3:369-388, 381

- ↑ Peer review and the acceptance of new scientific ideas[7] (Warning 469 kB PDF)For an opposing perspective, e.g. Peer Review as Scholarly Conformity[8]

- ↑ Churchland P Matter and Consciousness: A Contemporary Introduction to the Philosophy of Mind (1999) MIT Press. p.90.

- ↑ Rothbart D "Demarcating Genuine Science from Pseudoscience", in Grim op cit p 114

- ↑ Kuhn TS (1962) The Structure of Scientific Revolutions Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-45808-3

- ↑ Lakatos (1977) The Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes: Philosophical Papers Volume 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; Science and Pseudoscience - transcript and broadcast of talk by Imre Lakatos