Integrated air defense system

An integrated air defense system puts all antiaircraft sensors (e.g., radar, visual observers, and other technical means) as well as antiaircraft weapons (e.g., anti-aircraft artillery, surface-to-air missiles, air superiority fighters and interceptors, etc., under a common system of command, control, communications and intelligence (C3I). Depending on the national doctrine involved, the control is more or less decentralized. NATO doctrine is concerned with deconfliction, but allowing a fighter pilot the discretion to pursue the final attack. Soviet doctrine, including that of Iraq, was more centralized and less flexible for the pilot.

Today's battlefield, in many respects, starts as a duel between the IADS and the suppression of enemy air defense campaign against it.

The first operational IADS, with no computer assistance other than in the brains of the defenders, was in the Battle of Britain.[1] The term IADS had not yet been invented, but more important was that the Germans did not see the British system as a system. They saw airfields, radars, etc., but did not grasp that the most critical and vulnerable part were the control centers. Indeed, some of the German radars of the time were more advanced, but were not as well integrated.[2]

Requirements of an IADS

The basic rules of an IADS are:

- Find the attackers

- Direct your defensive platforms (e.g., surface-to-air missiles (SAM), anti-aircraft artillery (AAA), etc.) against them

- Let your defensive platforms attack the enemy

- Don't let your defensive platforms attack your own side

Sensors

Radar is the backbone of modern IADS, and radar of many types: early warning, perhaps over-the-horizon early warning, "look down" airborne radar that can detect low-flying aircraft and cruise missiles, ballistic missile acquisition radar, missile fire control radar, ground- and air-based radar that direct fighters to their targets, missile guidance radar, to say nothing of weather radar to pick out routes that the enemy may try and that your forces can use. Still, it is possible to become overdependent on radar, or make too many assumptions that you are superior to the enemy's radar.

Some Soviet/Russian SAMs, such as the 2K12 (NATO reporting name SA-6 GAINFUL), have, in addition to radar, electro-optical assistance to visual guidance. [3] These were a rude surprise to NATO forces that believed they had destroyed all Serbian radars, or forced them to shut down. Anthony Cordesman observed that a lesson learned from the Kosovo campaign was "the continuing survivability of land-based air defenses, and the threat posed by “non-cooperative” air defenses that do not emit or deploy in ways that can be easily targeted. According to NATO figures, some 90% of Serbia’s SA-6 assets survived the war, and could fire using pop-up radar and/or electro-optical techniques at the end of the war." Further, he observed that modern air and missile power can achieve very high levels of suppression, [but\ cannot kill mobile systems or prevent land-based systems from riding out an extensive..."suppression of enemy air defense (SEAD) campaign. In contrast to the Iraqi KARI [4] IADS was largely made up of fixed assets.

Command and control

Today, if the enemy knows where your IADS command is located, and it is not mobile and well-defended, he will make it a high priority to kill. It becomes a center of gravity of one's defense. This was not true in the Battle of Britain; the Germans did not fully understand the network of sector stations linked to one another and to Fighter Command, and they did not have the precision-guided munitions to achieve sure kill on the command posts if they knew their significance.

Iraqi IADS command posts, however, were some of the first targets of the 1991 Operation Desert Storm attack, although an early warning radar was the very first target. The latter was on the Saudi-Iraq border, and was unconventionally attacked by Army AH-64 Apache attack helicopters, led to the target by Air Force Special Operations CH-53 PAVE LOW helicopters with advanced low-level navigation.

While Airborne Warning and Control Systems (AWACS) such as the E-3 Sentry or Russian Beriev A-50 seem safe in the air, that depends on the sophistication of the opponent. It is unlikely that a fighter can claw through the escorts surrounding an AWACS, but long-range air-to-air missiles that also have an anti-radiation missile capability may get through. The Soviet/Russian Vympel R-33/AA-9 AMOS has been considered an "AWACS killer". Longer-ranged versions of the U.S. AIM-120 AMRAAM may have the same capability toward the other side.

Air defense platforms

Deconfliction

Deconfliction is one of the key aspects of an IADS. In general, there are a series of concentric circles around a target: the outermost might be assigned to long-range fighters, the next to long-range SAMs, the next to shorter-range fighters, and the innermost to AAA and short-range SAMs. These circles may be three-dimensional; there may be a rule that while aircraft at high altitude over troop concentrations are not to be engaged by the ground missiles, if they descend below a given altitude, they become targets.

Some IADS will mix systems in an IADS, either accepting a certain probability of fratricide,[5] or relying on identification friend or foe and other electronics to avoid fratricide.

Both air force and air defense force [Egyptian] commanders

confirmed that, while it was an operational goal to use the MiG-21 as the first force to engage enemy aircraft at maximum range, it also was tactical doctrine for the interceptors to fight within the missile belt and continue harrying attacking forces all the way to their targets. They agreed that losses from friendly missiles were so relatively small that the tactics of using both interceptors and missiles in the same airspace was operationally sound and militarily

effective against the offensive formations.[6]

IADS over time

Battle of Britain

See Battle of Britain for the operational doctrine, and a somewhat more technical description fo the Chain Home radars.

Kammhuber Line

Named after its architect and commander, Generalleutnant Josef Kammhuber of the Luftwaffe, this IADS, originally extending to the French coast, defended Germany from World War II strategic bombing. Obviously, its western installations were lost as the Allies moved inland, but the German defenses were still very credible. The radars were technically excellent, and one of the major problems was Adolf Hitler's unwillingness to invest in defensive systems.

NATO

North America

Soviet Union

North Vietnam

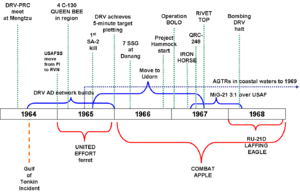

While the North Vietnamese had relatively little air defense when first bombed after the Gulf of Tonkin Incident, they steadily improved. As a very significant difference from the Korean War, North Vietnamese air defenses moved quickly to integrate radar, command post, ground observers, anti-aircraft artillery, and, when the Soviets supplied them, surface-to-air missiles.

By 1960, the U.S. was starting to direct strategic SIGINT at North Vietnam, to understand their air defense as well as other structures.

Their best fighter was the MiG-21, but they had pilots who could get good results with obsolescent aircraft such as the MiG-17.

After a regiment of PRC MiG-17 fighters arrived at Mengtzu in 1963, SIGINT predicted jet fighters would enter the DRV air defense network. This was reinforced with learning that high-level DRV and PRC personnel would have a meeting at Mengtzu in May 1964.[7]

The Gulf of Tonkin incident, in August 1964, involved DESOTO patrols by destroyer equipped with intercept vans, backed up with carrier air patrols and additional destroyers. [8].

Early DRV Air Defense Buildup

In the weeks immediately following the Gulf of Tonkin incident, the most important SIGINT role was providing defensive information to US air strikes. This was done at three levels of generality. First, overall monitoring of the DRV air defense network, SIGINT could maintain situational awareness of North Vietnamese tracking via radar and visual observers. Second, SIGINT detected the activation of specific weapons systems in the air defense network, such as SA-2 surface-to-air missiles (SAM), anti-aircraft artillery (AAA), and fighter interceptors. Finally, it could detect immediate threats, such as missile launches or impending attacks by fighters.[7]

Reports from the roughly 40 visual observation stations were sent to sector headquarters, which controlled AAA. These reports were sent by high-frequency (HF) radiotelegraphy, in standardized message formats where only the specific details needed to be transmitted. It could take up to 30 minutes for a report to work its way through the system, so that more specific tracking or interception orders could be given. According to the NSA history, air defense communications did not change significantly during the war, so COMINT analysts were able to become very familiar with its patterns and usage.

Command and control applied to four system components: air warning from radar and observer stations, limited radar tracking, AAA and SAMs, and fighters. Rapid upgrades started to go into place after the Gulf of Tonkin incident, with the arrival, within two days, of 36 MiG-15 and MiG-17 fighters. These arrived from China and were probably flown, at first, by Chinese pilots, but Vietnamese pilots were soon in familiarization flights.

Two main communications links between the DRV and PRC were established, from Hanoi to Kuangchow and K'unming. These liaison networks allowed access to Chinese radar covering the Gulf of Tonkin, Laos, and Hainan Island, as well as the DRV itself. Air Defense headquarters was at Bac Mai.

The DRV system matures, 1964

Air Defense headquarters was at Bac Mai. North Vietnam's air defense system, as of 1965, had three main subsystems:

In 1964, no one had much experience with surface-to-air missiles, for which North Vietnam primarily aSovet S-75 Dvina (NATO designation SA-2 GUIDELINE).

In 1965, the DRV had full radar coverage, with Chinese input, out to 150 miles from its borders. Detection and processing times dropped to five minutes. In contrast, the US did not have full radar coverage over the DRV, and SIGINT was seen as a way of filling the gaps in US knowledge of their air defense operations. [7]

By January 1966, all major air defense installations, including those in the PRC, were linked by a common HF radio network with standardized procedures. There was an Air Situation Center and an Air Weapons Control Staff. The latter assigned targets to the various defense weapons. By 1967-1968, there were approximately 110,000 persons in the DRV air defense system, supporting 150 radars, 150 SAM sites (rarely all active at the same time), and 8,000 AAA pieces. There were 105 fighters, including the MiG-21. At any given time, one-third to one-half of the fighters were based at PRC airfields.

A wider range of communications systems emanated from Air Defense Headquarters, including [[ITU frequency bands|VHF voice}}, landlines, and HF/MF. Due to the need to move information quickly, without any automation, most communications were either in low-grade ciphers or were unencrypted.

1967 Arab-Israeli war

Iraq 1991

Iraq's IADS, called KARI, was built by the French defense contractor, Thomson-CSF, and, at first, seemed incredibly deadly. It also connected to a British-built logistics and battle management system called ASMA. It was, however, intended to stop raids of 20-40 aircraft, as might come from Israel or Iran, not a massive attack. While it used Soviet doctrine, there was a huge difference between challenging KARI and challenging the multiple systems of PVO Strany, the Soviet air defense service.[9]

Its most fundamental flaw, however, was not the mixture of French and Soviet sensors, missiles, aircraft, and artillery, but that its command and control was cut from the fairly rigid Soviet model, and made even more rigid to suit the personality of Saddam Hussein and his immediate circle. France and NATO often put their best pilots, most likely to improvise, into air defense, but Iraq wanted to control them tightly. [10]

The Iraqis considered ground attack their most important air warfare mission, and put their best pilots into their Mirages, as opposed to their Soviet air superiority aircraft such as the MiG-25 and MiG-29[11]

KARI had three levels:

- National/strategic, operated by the Iraqi Air Force

- Key point defense, operated by the Republican Guard

- Mobile, operated by the Iraqi Army

Iraqi air defense weapons and infrastructure were substantial,; their training and doctrine were the most limiting factors.[12] [13]

See KARI: Iraqi air defense for the actual equipment and estimated number. This section focuses more on the KARI architecture and doctrine.

Balkans

In 1999, Kosovo kept up an IADS for a surprising amount of time [3] While there has not been official confirmation, the SA-6 may have been involved in shooting down a U.S. F-117 Nighthawk "stealth" fighter over Kosovo in 1999. Actual detection may have used an older long-wave radar, with the SA-6 fired using electro-optical guidance. When the missile threatened the F-117, the latter may have maneuvered away, and into the path of fighters or AAA. [14]

References

- ↑ Royal Air Force, Battle of Britain

- ↑ Clark, Gregory C. (March 1997), Deflating British Radar Myths of World War II, Air Command and Staff College, ADA397960

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Cordesman, Anthony H. (August, 2000), The Effectiveness of the NATO Tactical Air and Missile Campaign Against Serbian Air and Ground Forces in Kosovo: A Working Paper, Center for Strategic and International Studies

- ↑ a French-built system; KARI is the French word "Irak" spelled backwards

- ↑ Press, Michael C. (09 June 1978), Tactical Integrated Air Defense System, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, ADA057830

- ↑ Hotz, Robert, Offense, Defense Tested in 1973 War, Both Sides of the Suez: Airpower In the Mideast, Aviation Week and Space Technology

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Hanyok, Robert J. (2002), Chapter 6 - Xerxes' Arrows: SIGINT Support to the Air War, 1964-1972, Spartans in Darkness: American SIGINT and the Indochina War, 1945-1975, Center for Cryptologic History, National Security Agency

- ↑ National Security Agency (11/30/2005 and 05/30/2006). Gulf of Tonkin. declassified materials, 2005 and 2006. Retrieved on 2007-10-02.

- ↑ Trainor, Michael R. (1995), The Generals' War: The Inside Story of the Conflict in the Gulf, Little, Brown

- ↑ Clark, Robert (2000), Symmetrical Warfare and Lessons for Future War: the Case of the Iran-Iraq Conflict, Canadian Forces College, Advanced Military Studies Course 3

- ↑ United States Gulf War Air Power Survey, vol. IV: Weapons, Tactics, and Training and Space Operations, Air Force Historical Research Agency, 1993

- ↑ Vallance, Andrew, Air Power in the Gulf War - The Conduct of Operations, Royal Air Force

- ↑ Cordesman, Anthony (9/26/2003), Chapter XI: Command, Control, Communications, Intelligence and Battle Management, The Lessons of Modern War: Volume II, The Iran-Iraq War, Center for Strategic and International Studies

- ↑ A Lost Illusion