Golden ratio: Difference between revisions

imported>Malcolm Schosha (adding some to clarify) |

imported>Meg Taylor No edit summary |

||

| (23 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

{{Image|Altes Rathaus Leipzig.jpg|right| | {{Image|1000px Golden Rectangle Construction.png|right|250px|demonstrating a simple method to construct a Golden Ratio rectangle}} | ||

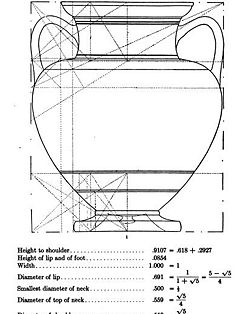

{{Image|Lacey D. Caskey, The Geometry of Greek Vases, p.37.jpg|right|250px|illustrating geometric proportions in an Attic Greek amphora, including the Golden Proportion: .618}} | |||

{{Image|Altes Rathaus Leipzig.jpg|right|250px|The old [[townhall]] in [[Leipzig]]. The tower is positioned between the right (a) and left (b) sections so that <math>\scriptstyle \frac{a}{b}</math> equals the golden ratio.}} | |||

The '''golden ratio''' | The '''golden ratio''' is a mathematical proportion that is important in the arts and interesting to mathematicians. In architecture and painting, some works have been proportioned to approximate the golden ratio ever since antiquity. The ratio itself is also known as the '''mean and extreme ratio''', the '''golden section''', the '''golden mean''', and the '''divine proportion'''. The earliest existing description is found in the Elements of Euclid (Book 5, definition 3): ''A straight line is said to have been cut in extreme and mean ratio when, as the whole line is to the greater segment, so is the greater to the less''. | ||

[[Johannes Kepler]] took considerable interest in the subject, and in his 1596 book, ''Mysterium Cosmographicum'', wrote: | |||

<blockquote>Geometry has two great treasures; one is the Theorem of Pythagoras; the other, the division of a line into extreme and mean ratio. The first we may compare to a measure of gold, the second we may name a precious jewel.</blockquote> | |||

Kepler seems to have particularly associated this ratio with forms of plants, and all organic growth.<ref>[http://www.keplersdiscovery.com/DivineProportion.html] Kepler's Discovery, the Divine Proportion, </ref> In more recent years [[Jay Hambidge]] wrote several books devoted entirely to the Golden ratio, pointing out many instances of its presence on organic forms, as well as in the art and architecture of Attic Greece. | |||

It has been claimed that the golden ratio is found in the proportions of architectural structures ranging from the [[Great Pyramid of Giza]]<ref>[http://www.dartmouth.edu/~matc/math5.geometry/unit2/unit2.html]''The Golden Ratio & Squaring the Circle in the Great Pyramid'', Paul Calter</ref>, to the [[Parthenon]]<ref>[http://community.middlebury.edu/~harris/Humanities/TheGoldenMean.html] ''The Golden Mean'', William Harris</ref>, to [[Chartres Cathedral]]<ref>[http://www.johnjames.com.au/chartres-shorthistory.shtml] ''Chartres Cathedral'', John James</ref>. In the 20th century, the golden section was applied by the French architect [[Le Corbusier]]<ref>[http://www.archsociety.com/e107_plugins/content/content.php?content.24] ''Working With Corbusier'', Jerzy Soltan</ref>, who used the proportion in the design of virtually all his architectural works, and in his painting, and who wrote a series of books on the subject called ''The Modulor''<ref>[http://books.google.com/books?id=5ja-3GavJssC&dq=The+Modulor&printsec=frontcover&source=bn&hl=en&ei=vcmnSr8akqo26ri5qwg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=8#v=onepage&q=&f=false] ''The Modulor'', vol.1, Le Corbusier</ref>. | |||

==Properties== | ==Properties== | ||

To elaborate: if there is a longer line segment <math>\scriptstyle a\ </math> and a shorter line segment <math>\scriptstyle b\ </math>, and if the ratio between <math>\scriptstyle a + b\ </math> and <math>\scriptstyle a\ </math> is equal to the ratio between the line segment <math>\scriptstyle a\ </math> and <math>\scriptstyle b\ </math>, this ratio is the golden ratio <math>\scriptstyle \Phi = \frac{a}{b} = \frac{a+b}{a}</math>. | |||

Rewriting this definition gives | |||

:<math>\Phi = \frac{a}{b}= \frac{a+b}{a} = 1+\frac{b}{a} = 1+ \frac{1}{\Phi}</math>, | |||

which leads to | |||

:<math>\Phi^2 - \Phi - 1 = 0 </math>, | |||

a [[quadratic equation]] with the solutions | |||

:<math>\Phi =\frac{1 + \sqrt{5}}{2} = 1 + \frac{1}{\Phi} = 1{,}618\,033\,988\dots</math> . | |||

and | |||

:<math>\bar \Phi=\frac{1 - \sqrt{5}}{2}= 1 - \Phi= -\frac{1}{\Phi} = -0{,}618\,033\,988\dots</math> | |||

With <math>\Phi = 1 + \frac{1}{\Phi}</math> we could derive the infinite [[continued fraction]] of the golden ratio: | With <math>\Phi = 1 + \frac{1}{\Phi}</math> we could derive the infinite [[continued fraction]] of the golden ratio: | ||

| Line 25: | Line 38: | ||

where <math>\ F_n</math> is the n-th term of the [[Fibonacci number|Fibonacci sequence]]. | where <math>\ F_n</math> is the n-th term of the [[Fibonacci number|Fibonacci sequence]]. | ||

== References == | |||

{{reflist}} | |||

Latest revision as of 19:54, 1 November 2013

The golden ratio is a mathematical proportion that is important in the arts and interesting to mathematicians. In architecture and painting, some works have been proportioned to approximate the golden ratio ever since antiquity. The ratio itself is also known as the mean and extreme ratio, the golden section, the golden mean, and the divine proportion. The earliest existing description is found in the Elements of Euclid (Book 5, definition 3): A straight line is said to have been cut in extreme and mean ratio when, as the whole line is to the greater segment, so is the greater to the less.

Johannes Kepler took considerable interest in the subject, and in his 1596 book, Mysterium Cosmographicum, wrote:

Geometry has two great treasures; one is the Theorem of Pythagoras; the other, the division of a line into extreme and mean ratio. The first we may compare to a measure of gold, the second we may name a precious jewel.

Kepler seems to have particularly associated this ratio with forms of plants, and all organic growth.[1] In more recent years Jay Hambidge wrote several books devoted entirely to the Golden ratio, pointing out many instances of its presence on organic forms, as well as in the art and architecture of Attic Greece.

It has been claimed that the golden ratio is found in the proportions of architectural structures ranging from the Great Pyramid of Giza[2], to the Parthenon[3], to Chartres Cathedral[4]. In the 20th century, the golden section was applied by the French architect Le Corbusier[5], who used the proportion in the design of virtually all his architectural works, and in his painting, and who wrote a series of books on the subject called The Modulor[6].

Properties

To elaborate: if there is a longer line segment and a shorter line segment , and if the ratio between and is equal to the ratio between the line segment and , this ratio is the golden ratio .

Rewriting this definition gives

- ,

which leads to

- ,

a quadratic equation with the solutions

- .

and

With we could derive the infinite continued fraction of the golden ratio:

Thus

- ,

where is the n-th term of the Fibonacci sequence.