9-11 Attack in New York

Not only was the 9-11 Attack impactful on the world, it had many special effects in New York City. Prior to it, the worst line-of-duty death toll in the Fire Department of New York was 12, in the Wonder Drug & Cosmetics fire on 17 October 1966.[1] Prior to it, the most massive high-rise incident was the 1993 World Trade Center bombing.

World Trade Center

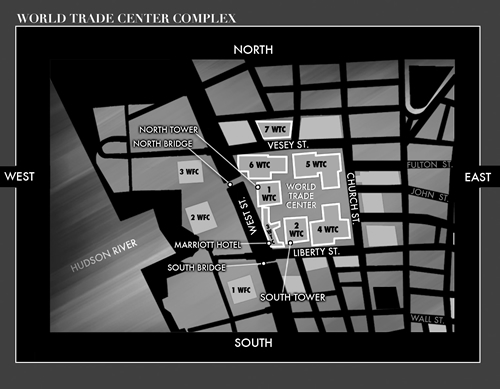

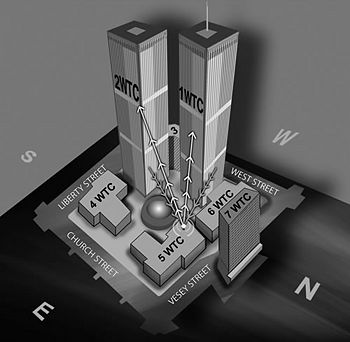

To understand the operational context, it must be realized that the World Trade Center contains a number of buildings beyond those hit by the aircraft, WTC1 (North Tower) and WTC2 (South Tower), both 110-story structures. There are also a number of critical infrastructure functions under the entire complex.

Debris damaged other buildings in the complex, some, such as WTC7, to the point that they collapsed. Other buildings were damaged beyond economic repair.

Other building complexes nearby, such as the World Financial Center (WFC), were also affected.

First response

There was no all-service universal emergency telephone number system in New York, in the sense that dispatchers receiving 911 telephone calls could invoke the appropriate response. The 911 call service had approximately 1,200 operators, radio dispatchers, and supervisors, all civilian employees of the NYPD. When a 911 call concerned a fire, it was transferred to the fire department dispatch center.

WTC1 was hit at 8:46 AM and WTC2 at 9:03. WTC2, the South Tower, collapsed first.

The first senior fire officer to arrive at the scene was Battalion Chief Joseph Pfeifer. Among his first acts was to set up the overall communications system.

Command and control

There were serious problems of command and control both among the various emergency response agencies (Fire, Police, Transit Authority Police, etc.) and within individual agencies. The Incident Command System never functioned on an interagency basis, nor was a Joint Command Post supporting the site created under ICS standards.

In July 2001, Mayor Giuliani updated a directive titled "Direction and Control of Emergencies in the City of New York." Its purpose was to eliminate "potential conflict among responding agencies which may have areas of overlapping expertise and responsibility." The directive sought to accomplish this objective by designating, for different types of emergencies, an appropriate agency as "Incident Commander." This Incident Commander would be "responsible for the management of the City's response to the emergency," while the OEM was "designated the 'On Scene Interagency Coordinator.'"[2]

Nevertheless, the FDNY and NYPD each considered itself operationally autonomous. As of September 11, they were not prepared to comprehensively coordinate their efforts in responding to a major incident. The OEM had not overcome this problem.

Multiple police departments had jurisdiction, but had little to no interoperable communications with the FDNY. When NYPD helicopters saw the top of the building start to sag, an imminent warning of collapse, they were unable to radio this to the FDNY.

Office of Emergency Management

There was a citywide Office of Emergency Management, which had three basic functions.

- OEM's Watch Command was to monitor the city's key communications channels-including radio frequencies of FDNY dispatch and the NYPD-and other data.

- improve New York City's response to major incidents, including terrorist attacks, by planning and conducting exercises and drills that would involve multiple city agencies, particularly the NYPD and FDNY.

- managing the city's overall response to an incident. After OEM's Emergency Operations Center was activated, designated liaisons from relevant agencies, as well as the mayor and his or her senior staff, would respond there. In addition, an OEM field responder would be sent to the scene to ensure that the response was coordinated.

The OEM's headquarters was located at 7 WTC. Some questioned locating it both so close to a previous terrorist target and on the 23rd floor of a building (difficult to access should elevators become inoperable). There was no backup site.

Fire Department of New York

At about 9:00 a.m., the Chief of Department took over as Incident Commander. At that time, he moved the Incident Command Post from the lobby of WTC 1 to a spot across West Street, an eight-lane highway, because of falling debris and other safety concerns. Chief officers considered a limited, localized collapse of the towers possible, but did not think that they would collapse entirely.

In what proved to be a catastrophic decision, but was not inconsistent with existing doctrine for high-rise building fires, senior chiefs moved to the South Tower.

At the Pentagon, the ICP was always in an Arlington County Fire Department mobile command post.

A Field Communications Van did arrive, but officers above the building operations level stayed in the South Tower.

New York Police Department

Port Authority Police

The WTC is leased by the Port of New York Authority, an interstate organization that has its own police force. Its officers receive more firefighting and rescue training than do regular police officers.

Rescue operations

Since most high-rise fires are contained to several floors, and there is normally a fire command room in the building, with access to its internal communications, sensors, and sprinklers, this has some merit for smaller fires. Once the decision was made, however, that the fire could not be extinguished, and the operation was one of rescue, it would have been wise for the overall Incident Commander to move outside the immediate area. An Operations Commander did need to stay with each major fire.

Pfeifer was properly relieved, under Incident Command System doctrine, by Assistant Chief Joseph Callan. Assistant Chief Callan commanded North Tower operations. Deputy Chief Peter Hayden was assigned as his assistant.

Radio systems

There was also a need to communicate throughout the complex, but there were technical problems with radio communications. [3] Communications to the upper stories had been a problem in 1993, so the FDNY had asked building personnel to activate the repeater system, which boosted the signal to the upper stories. One button on the repeater system activation console in the North Tower was pressed at 8:54, though it is unclear by whom. As a result of this activation, communication became possible between FDNY portable radios on the repeater channel. In addition, the repeater's master handset at the fire safety desk could hear communications made by FDNY portable radios on the repeater channel. The activation of transmission on the master handset required, however, that a second button be pressed. That second button was never activated on the morning of September 11.

At 9:05, FDNY chiefs tested the WTC complex's repeater system. Because the second button had not been activated, the chief on the master handset could not transmit. He was also apparently unable to hear another chief who was attempting to communicate with him from a portable radio, either because of a technical problem or because the volume was turned down on the console (the normal setting when the system was not in use). Because the repeater channel seemed inoperable-the master handset appeared unable to transmit or receive communications-the chiefs in the North Tower lobby decided not to use it.The repeater system was working at least partially, however, on portable FDNY radios, and firefighters subsequently used repeater channel 7 in the South Tower.

North Tower collapse

At 9:28 a.m., Callan broadcast on the two radio channels in use orders that firefighters leave the north tower. "Everyone come down out of the building. Leave the building immediately," Callan said, according to an interview he gave retired FDNY Chief Vincent Dunn. But few in the north tower heard his order - and when the building collapsed an hour later, Pfeifer's brother, Kevin, was among the dead.[3]

South Tower collapse

Assistant Chiefs Donald Burns and Jerry Barbara were designated as operations commanders for the South Tower. Both died in the collapse at 9:58. [4]

Immediate response to the collapse

Assistant Chief Frank Fellini had established an operations command post and was directing the post-collapse rescue efforts. Further up West Street, at Chambers Street, Chief Frank Cruthers had set up incident command. Chief Nigro assumed command of the incident at that location.

Recovery operations

Environmental effects

Lessons learned

References

- ↑ Terry Golway (2002), So Others Might Live: A History of New York's Bravest, the FDNY from 1700 to the Present, Basic Books, ISBN 0465027407, pp. 219-226

- ↑ National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, Chapter 9: Heroism and Horror, 9-11 Commission Report

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Al Guart, "9/11 Probers Grill FDNY Fire Hero", New York Post

- ↑ Daniel Nigro (2002), "Report from the Chief of Department", Fire Engineering