Scylla (sea monster)

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

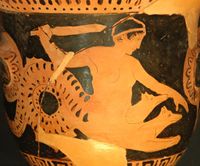

In ancient Greek mythology, Scylla was a female sea monster who attacked and devoured mariners. Ovid described her as six-headed, with legs made of snakes.

The following account of Scylla's creation is from Bulfinch's The Age of Fable[1], which is a retelling of the account from Ovid's Metamorphoses[2].

Glaucus said to Circe: “Goddess, I entreat your pity; you alone can relieve the pain I suffer…I love Scylla. I am ashamed to tell you how I have sued and promised to her, and how scornfully she has treated me. I beseech you to use your incantations, or potent herbs, if they are more prevailing, not to cure me of my love,--for that I do not wish,-- but to make her share it and yield me a like return.”

To which Circe replied, for she was not insensible to the attractions of the sea-green deity, “You had better pursue a willing object; you are worthy to be sought, instead of having to seek in vain. Be not diffident, know your own worth. I protest to you that even I, goddess though I be…should not know how to refuse you. If she scorns you scorn her; meet one who is ready to meet you half way, and thus make a due return to both at once.”

To these words Glaucus replied: “Sooner shall trees grow at the bottom of the ocean, and the sea weed at the top of the mountains, than I will cease to love Scylla, and her alone.”

The goddess was indignant, but she could not punish him, neither did she wish to do so, for she liked him too well; so she turned all her wrath against her rival, poor Scylla.

[Jumping ahead to the next time Scylla bathed in the sea, due to Circe’s powers:] The lower half of Scylla’s body was turned into a bunch of writhing sea serpents and barking monsters, still attached to her body. Scylla remained rooted to the spot. Her temper grew as ugly as her form, and she took pleasure in devouring hapless mariners who came within her grasp… till at last she was turned into a rock, and as such still continues to be a terror to mariners.

Ovid describes how Scylla ends up as a rock[3]:

Glaucus, {still} in love, bewailed {her}, and fled from an alliance with

Circe, who had {thus} too hostilely employed the potency of herbs.

Scylla remained on that spot; and, at the first moment that an

opportunity was given, in her hatred of Circe, she deprived Ulysses of

his companions. Soon after, the same {Scylla} would have overwhelmed the

Trojan ships, had she not been first transformed into a rock, which even

now is prominent with its crags; {this} rock the sailor, too, avoids.

Metamorphoses translator Henry Riley's commentary on Scylla the rock's location and danger, along with a neighboring hazard called Charybdis[4]. Many mariners were reputed to have been wrecked between the two sea hazards, traditionally believed to have been situated in the Strait of Messina:

According to some authors, Scylla was the daughter of Phorcys and Hecate; but as other writers say, of Typhon. Homer describes her in the following terms:-- ‘She had a voice like that of a young whelp; no man, not even a God, could behold her without horror. She had twelve feet, six long necks, and at the end of each a monstrous head, whose mouth was provided with a triple row of teeth.’ Another ancient writer says, that these heads were those of an insect, a dog, a lion, a whale, a Gorgon, and a human being. Virgil has in a great measure followed the description given by Homer. Between Messina and Reggio there is a narrow strait, where high crags project into the sea on each side. The part on the Sicilian side was called Charybdis, and that on the Italian shore was named Scylla. This spot has ever been famous for its dangerous whirlpools, and the extreme difficulty of its navigation. Several rapid currents meeting there, and the tide running through the strait with great impetuosity, the sea sends forth a dismal noise, not unlike that of the howling or barking of dogs, as Virgil has expressed it, in the words, ‘Multis circum latrantibus undis.’

Notes

- ↑ Bulfinch's Mythology: The Age of Fable, by Thomas Bulfinch, 1855, Chapter VII, from Project Gutenberg, last access 1/10/2021

- ↑ Metamorphoses XIV.1-74 by Ovid, translated with notes by Henry Riley, from Project Gutenberg, last access 1/10/2021

- ↑ Metamorphoses XIV.1-74 by Ovid, translated with notes by Henry Riley, from Project Gutenberg, last access 1/10/2021

- ↑ Metamorphoses XIV.1-74 by Ovid, translated with notes by Henry Riley, from Project Gutenberg, last access 1/10/2021