Telescope

The word "telescope" comes from two Greek words: tele (τηλε)[1] meaning “far” or “distant”, and skopein (σκοπειν) meaning “to see.” Together they simply mean “to see from far away.[2]

A simple description of telescope is an instrument designed to magnify distant objects so that they can be viewed more easily. Telescopes historically have been constructed of lenses and mirrors which concentrate visible light into a smaller and more defined image.[3]

Telescopes as research tools

Zik (2001) notes that before the telescope scientific observation relied on instruments such as Heron's diopter, Levi Ben Gershom's cross-staff, Egnatio Danti's torqvetto astronomico, Tycho's quadrant, Galileo's geometric military compass, and Kepler's ecliptic instrument. At the beginning of the 17th century, however, it was unclear how an instrument such as the telescope could be employed to acquire new information and expand knowledge about the world. To exploit the telescope as a device for astronomical observations Galileo had to establish that telescopic images are not optical defects, imperfections in the eye of the observer, or illusions caused by lenses; and develop procedures for systematically handling errors that may occur during observation and measurement and methods of processing data. Galileo made it clear that in order to measure and interpret natural phenomena accurately, a suitable method and instrument would need to be developed. Historians of science explore the linkage established by Galileo among theory, method, and instrument, in his case the telescope. Although the telescope was not invented through science, Galileo used optics to employ a theory-laden instrument for bridging the gulf between picture and scientific language, between drawing and reporting physical facts, and between merely sketching the world and actually describing it.[4]

History of the development of the telescope

Leonard Digges (1520-1559)

Leonard Digges was a writer of mathematics and science in English, one of the first people to popularise work in either field. He was also a surveyor who invented the theodolite, the telescope, the reflecting telescope and possibly the refractive telescope a considerable amount of time before Galileo ever heard of telescopes. His influences in turn may predate his work by about 300 years because there is reason to believe that he encountered Roger Bacon's Opus Majus, (ca 1267) in the library of a friend, John Dee, and learned how lenses could be used to change the appearance of distant objects, specifically the Sun, Moon and stars.

He published a number of works during his lifetime that clearly established him as a mathematician and student of astronomy with a pronounced ability in application but his achievements were expanded and revised by his son Thomas and published after Leonard's death, some of the work for the first time. Historically, it is difficult to separate the works of Leonard and Thomas due to the manner in which Thomas edited and published his father's works.

There is clear evidence that he and his son Thomas did understand the design and function of telescopes. However the only evidence that Leonard actually used a telescope is offered by his son Thomas. For this reason, Hans Lipperhey is credited by many authorities with having invented the telescope.[5][6][7][8][9]

John Dee

John Dee was a mathematician of renown and while he holds no claim to having invented the telescope, Dee was the guardian of Leanard Digges' son, Thomas Digges, following the death of Leonard, and had a hand in his education and support in his efforts. Dee is also a sources for the origins of the telescope. Dee noted in a preface to Billingsley's translation of Euclid (1570) what he refers to as Perspective glasses, a term used by Thomas Digges in Pantometria (the word telescope was actually coined in the 17th century). In this preface Dee offers advice to the military commanders on how to obtain information about enemy forces:

- He may wonderfully helpe him selfe, by Perspective glasses. In which (I trust) our posterity will prove more skillfull and expert, and to greater purposes, than in these days, can (almost) be credited to be possible.[9]

Thomas Digges (1543-1595)

In 1571, Thomas Digges published Leonard Digges's book on the telescope, Pantometria, twelve years after his father's death. Panometria was the first publications to discuss the invention of the telescope in English. Thomas had extended, revised and enhanced the book and he wrote the preface. J J O'Connor and E F Robertson note that while the description of how lenses could be combined to construct a telescope, there is no known evidence that the Diggeses did actually make a telescope and use one. Some authorities take exception to this view and regard the issue to be resolved. How is that the Diggeses knew how to construct a telescope and yet did not? Having constructed a telescope how is it they would not have used it? In his preface to the Pantometria, published the year after John Dee's Preface to Euclid, Thomas noted specifically how his father had observed things with "Perspective glasses' on numerous occasions from a considerable distance and with witnesses present. Thomas wrote:

- ..... my father by his continual pain-full practices [practical experiments], assisted with Demonstrations Mathematicall, was able and sundrie Times hath by proportionall Glasses duly situate in convenient angles, not onely discovered things farre off, read letters, numbered peeces of money with the very coyne and superscription thereof, cast by some of his freends of purpose uppon Downes in open fields, but also at seven miles declared what had been doon at that instant in private places.....

This is clear evidence to some authorities that Thomas was describing a telescope that had indeed been constructed and used. The absence of specific notes on the use of a telescope are therefore not to be regarded as proof that the Diggeses, father and son, never made nor used a telescope.

Colin Ronan and Gilbert Satterthwaite built a working telescope in 2002 from a description provided in a report on military and naval inventions, written in 1578 William Bourne, for Lord Burghley, Elizabeth I's Secretary of State. Essentially, this shows that it wass an invention that predates the claims for the invention by the Hans Lipperhey by at least 30 years. Considering that the Pantometria was published 12 years after Leonard's death it is not unreasonable to assume that the telescope may have been invented by as much if not more than a half century before Hans Lipperhey.[9]

Thomas’s publication, Alae seu scalae mathematicae, in 1573, was a Latin text prompted by the new star of 1572, a supernova.[10] Thomas's observations were employed by Tycho Brahe in his work. The supernova created quite a stir worldwide and certainly in Europe. There was a tremendous increase in astronomical and astrological work and publications. Tycho Brahe's supernova was significant because it encouraged astronomers in the 16th-century to question their perception that the heavans were immutable, that is, unchanging. Thomas's contribution was to determined the nova's position and his conclusion that its appearance was a challenge to traditional cosmology of the day. [5][6][7][11][12][9]

Hans Lipperhey

Lipperhey (or Lippershey) was a Dutch spectacle maker who filed a patent for the refractive telescope in 1608. At that time there were several other patents pending. Lepperhey was apparently employed to make two lenses, one convex and the other concave. When the client appeared to take possession of the lens he positioned them to show how they magnified distant objects when used in tandem. Another claimant to the patent was the son of Sacharias Janssen. Janssen later noted that his father already had a telescope of Italian manufacture, dated 1590. These events predate Lipperhey’s claims.[9]

Galileo Galilei

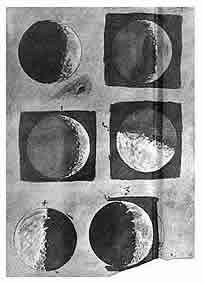

Galileo first heard of the telescope in 1609 and was able construct his own model from the description given him about the device patented by a spectacle maker in the Netherlands, Hans Lipperhey. He made several models including an 8-power telescope and a 20-power.[13] Galileo went on to make observations of the Moon, the Sun, the planets and stars [14]

Types of telescopes

See also

Bibliography

History

- Barker, P. and Goldstein, B. "Realism and instrumentalism in 16th century astronomy: a reappraisal." Perspectives on Science. 1998. v 6 #3: 232-257.

- Bedini, S. A. "The instruments of Galileo Galilei." Pp. 257-292 in R. McMullin, ed. Galileo Man of Science. (1967)

- Biagioli, Mario. Galileo's Instruments of Credit: Telescopes, Images, Secrecy. U. of Chicago Press, 2006. 302 pp.

- Chapman, A. Astronomical Instruments and Their Use: Tycho Brahe to William Lassel. (19960

- Dupré, Sven. "Galileo's Telescope and Celestial Light." Journal for the History of Astronomy 2003 34(4): 369-399. Issn: 0021-8286

- King, Henry C. The History of the Telescope (2003) 480pp

- Mccray, W. Patrick. "What Makes a Failure? Designing a New National Telescope, 1975-1984." Technology and Culture 2001 42(2): 265-291. Issn: 0040-165x. on New National Technology Telescope that was NOT built at Kitt Peak, Arizona, but did set design standards for the future. Fulltext: Project Muse

- Osterbrock, Donald E. Yerkes Observatory, 1892-1950: The Birth, near Death, and Resurrection of a Scientific Research Institution (1997) online edition

- Smith, R. W. "Engines of Discovery: Scientific instruments and the history of astronomy and planetary science in the US in the 20th century." Journal of the History of Astronomy 1997. 28: 49-77

- Van Helden, A. "Telescope and Authority From Galileo to Cassini." Osiris 1994. Vol. 9:9-29

- Van Helden, Albert. "Galileo and Scheiner on Sunspots: A Case Study in the Visual Language of Astronomy," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 140, No. 3 (Sep., 1996), pp. 358-396 in JSTOR

- Zik, Yaakov. "Science and Instruments: the Telescope as a Scientific Instrument at the Beginning of the Seventeenth Century." Perspectives on Science 2001 9(3): 259-284. Issn: 1063-6145 Fulltext: Project Muse

- Zimmerman, Robert. "More Light!" American Heritage of Invention & Technology 2002 18(2): 14-23. Issn: 8756-7296, on 1970s Fulltext: online

- Zirker, J. B. An Acre of Glass: A History and Forecast of the Telescope Johns Hopkins U. Press, 2005. 343 pp. excerpt and text search

Current

- Brunier, Serge, and Anne-Marie Lagrange. Great Observatories of the World (2005) 240pp; covers 56 observatories excerpt and text search

- McCray, W. Patrick Giant Telescopes: Astronomical Ambition and the Promise of Technology (2nd ed. 2006) excerpt and text search

References

- ↑ for example, télothen (τηλóθν), “from a distance” télourós (τηλουρóς), “far off.”

- ↑ [1], [2] & [3] S.C. Woodhouse (1910) Woodhouse's English-Greek Dictionary, The University of Chicago Library

- ↑ [4] from World Book at NASA for students adapted from "Telescope." The World Book Student Discovery Encyclopedia. Chicago: World Book, Inc., 2005.

- ↑ Yaakov Zik, "Science and Instruments: the Telescope as a Scientific Instrument at the Beginning of the Seventeenth Century." Perspectives on Science 2001 9(3): 259-284.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Gribbin, J. (2002) Science: A history. London: Penguin

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Thomas Digges: Gentleman and mathematician Stephen Johnston (1994) chapter 2 (pp. 50-106) of, ‘Making mathematical practice: gentlemen, practitioners and artisans in Elizabethan England’ Ph.D. thesis, Cambridge. Available through University of Oxford, Museum of History of Science

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Thomas Digges O'Connor, J. J. and Robertson, E. F. (2002) MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, School of Math and Statistics, University of St. Andrews.

- ↑ Leonard Digges Richard S. Westfall, Department of History and Philosophy of Science, Indiana University for the Galileo Project, Rice University

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Did the reflecting telescope have English origins? Colin A Ronan (1991). Leonard and Thomas Digges. Journal of the British Astronomical Association, 101, 6

- ↑ sometimes referred to as Tycho's Supernova See reference to NASA/ESA Space Telescope cited below.

- ↑ Thomas Digges Richard S. Westfall, Department of History and Philosophy of Science, Indiana University for the Galileo Project, Rice University

- ↑ heic0415: Stellar survivor from 1572 A.D. NASA/ESA Space Telescope. On Nov. 11, 1572, Tycho Brahe observed a star in the constellation Cassiopeia as bright as Jupiter which eventually equaled Venus in brightness. It was visible during daylight for about two weeks and eventually faded from unaided view altogether after about 16 months.

- ↑ Drake, Stillman (1973). "Galileo's Discovery of the Law of Free Fall". Scientific American v. 228, #5: 84-92

- ↑ Galilei, Galileo (1610). The Starry Messenger (Sidereus Nuncius). In Drake (1957):22-58