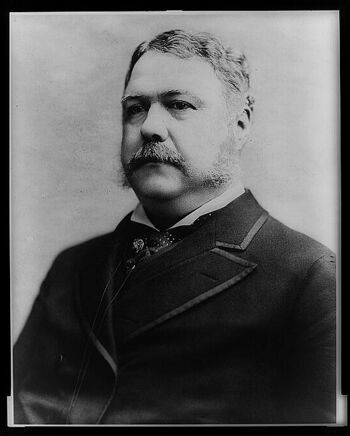

Chester A. Arthur

Chester Alan Arthur was the 21st president of the United States.

Arthur was born on October 5, 1829 in Fairfield, Vermont to a Baptist preacher who had emigrated from the north of Ireland. He graduated from Union College in 1848, taught school, was admitted to the bar, and practiced law in New York City. Early in the Civil War he served as Quartermaster General of the State of New York.

In 1871, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed him Collector of the Port of New York. Arthur effectively marshalled the thousand Customs House employees under his supervision on behalf of Roscoe Conkling's Stalwart Republican machine. Honorable in his personal life and his public career, Arthur nevertheless was a firm believer in the spoils system when it came under vehement attack from reformers. He insisted upon honest administration of the Customs House, but staffed it with more employees than it needed, retaining them for their merit as party workers rather than as government officials.

In 1878 President Rutherford B. Hayes, attempting to reform the Customs House, ousted Arthur. Conkling and his followers tried unsuccessfully to win redress by fighting for Grant's renomination at the 1880 Republican Convention. They reluctantly accepted the nomination of Arthur for the vice presidency.

During his brief tenure as vice president, Arthur stood firmly beside Conkling in his patronage struggle against President James Garfield. But when Arthur succeeded to the presidency, he was eager to prove himself above machine politics.

Avoiding old political friends, he became a man of fashion in his garb and associates, and often was seen with the elite of Washington, New York, and Newport. To the indignation of the Stalwart Republicans, the onetime Collector of the Port of New York became, as president, a champion of civil service reform. Public pressure, heightened by Garfield's assassination, forced an unwieldy Congress to heed the President.

In 1883, Congress passed the Pendleton Act, which established a bipartisan Civil Service Commission, forbade levying political assessments against officeholders, and provided for a "classified system" that made certain Government positions obtainable only through competitive written examinations. The system protected employees against removal for political reasons.

Acting independently of party dogma, Arthur also tried to lower tariff rates so that the government would not be embarrassed by annual surpluses of revenue. Congress raised about as many rates as it trimmed, but Arthur signed the Tariff Act of 1883. Aggrieved Westerners and Southerners looked to the Democratic Party for redress, and the tariff began to emerge as a major political issue between the two parties.

The Arthur administration enacted the first general federal immigration law. In 1882, Arthur approved a measure excluding paupers, criminals, and lunatics. Congress also suspended Chinese immigration for ten years, later making the restriction permanent.

Arthur demonstrated as president that he was above faction within the Republican Party, if indeed not above the party itself. Perhaps in part his reason was the well-kept secret he had known since a year after he succeeded to the Presidency, that he was suffering from a fatal kidney disease. He kept himself in the running for the presidential nomination in 1884 in order not to appear that he feared defeat, but was not renominated and died on November 18,1886 in New York City. Publisher Alexander K. McClure recalled, "No man ever entered the Presidency so profoundly and widely distrusted, and no one ever retired ... more generally respected."

Concerns about Arthur's Presidential eligibility

During Chester Arthur's Vice-Presidential campaign alongside James A. Garfield, Arthur P. Hinman, an attorney who had apparently been hired by the members of the Democratic party, explored the "rumors that Arthur had been born in a foreign country, was not a natural-born citizen of the United States, and was thus, by the Constitution, ineligible for the vice-presidency."[1] When Hinman's initial claim of a birth in Ireland failed to gain traction, he maintained instead that Arthur was born in Canada and lobbied the press for support while searching for Arthur's birth records, eventually in vain. After Arthur had become President due to Garfield's assassination, Hinman published a pamphlet aimed to cast doubt on Arthur's presidential eligibility.[2]

However, due to the focus on Hinman's unfounded allegations regarding Chester Arthur's foreign place of birth, it remained unknown during the Garfield campaign that Arthur was nevertheless a natural-born subject of the British crown,[3] because his British-Irish father William Arthur had not naturalized as a U.S. citizen until August 1843, fourteen years after Chester Arthur's birth in Vermont.[4]

Neither the law nor any federal court ruling in the United States has ever determined whether a natural-born British subject like Chester Arthur can at the same time also be a natural born citizen of the United States,[5] which is one of the constitutional requirements for the offices of President and Vice-President.[6] It is equally unclear whether Arthur was even a U.S. citizen at birth, because until the Civil Rights Act of 1866 there had been no federal citizenship rule for U.S. territory. He may have been a citizen of Vermont under the common law of the state, but the Fourteenth Amendment, which introduced ius soli into the United States Constitution, was ratified and adopted almost forty years after Arthur's birth. Even if applied retroactively, the 14th Amendment only covers born and naturalized citizens under complete U.S. jurisdiction,[7] while Arthur's status at birth was (at least in part) governed by British common law.

In 1882 Chester Arthur nominated Horace Gray as U.S. Supreme Court Justice, whose seminal decision in United States v. Wong Kim Ark extended the right of 14th Amendment citizenship to children born on U.S. territory of foreign parents, who have permanent residence and domicile in the United States.[8] If Arthur, by appointing Gray, ever intended to sanitize his problematic status with regard to natural born citizenship, he failed posthumously, because the court only ruled that Wong Kim Ark was a citizen, while Gray in fact indicated that Wong Kim Ark was not natural born.[9]

Arthur himself continuously gave false information on his family's history, thereby obscuring the circumstances and chronology of his own birth. Arthur defended himself against Hinman's original claim that he was not a native-born citzen[10] by stating that his father "came to this country when he was eighteen years of age, and resided here several years before he was married",[11] whereas in reality his father William emigrated from Ireland to Canada at the age of 22 or 23. Arthur further claimed that "his mother was a New Englander who had never left her native country—a statement every member of the Arthur family knew was untrue."[12] In a second interview he repeated some of the historical revisions and further stated that his father had been forty years of age at the time of his birth,[13] which was revealed by Hinman to be a lie.[14] Somewhere between 1870 and 1880 Chester Arthur had caused additional confusion by creating 1830 as a false year of his birth,[15] which was quoted in several publications[16] and was also engraved on his tombstone. Shortly before his death Arthur caused several Presidential materials, which had been in his private possession, to be destroyed,[17] while other historical documents pertaining to Arthur's life and presidency were lost for unknown reasons.[18]

Notes

- ↑ Thomas C. Reeves, Gentleman Boss. The Life and Times of Chester Alan Arthur, Newtown 1991, p. 202 sq.

- ↑ Arthur P. Hinman, How a British Subject Became President of the United States, New York 1884.

- ↑ William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England I.10 ("Of People, Whether Aliens, Denizens or Natives"), Oxford 1765-1769:

British common law with regard to patrilineal ius sanguinis and natural-born subjects of foreign birth was later codified in the British National and Status of Aliens Act of 1914.all children, born out of the king’s ligeance, whose fathers were natural-born subjects, are now natural-born subjects themselves, to all intents and purposes, without any exception;

- ↑ Cf. William Arthur's certificate of naturalization (v.s.), State of New York, 08-31-1843, in: Chester A. Arthur Papers, Library of Congress, Washington; first noted in: Leo C. Donofrio, "Supplemental Brief in Support of Application for Emergency Stay and/or Injunction", Wrotnowski v. Bysiewicz (Supreme Court of the United States), 08A469, 11-25-2008, based on research by Leo C. Donofrio (supervising attorney), Gregory J. Dehler (author of Chester Alan Arthur. The Life of a Gilded Age Politician and President, Hauppauge 2006) et al.

- ↑ The concepts of natural-born subject and natural born citizen were however specificially differentiated in United States v. Rhodes (27 Fed. Cas. 785, 1866) and reiterated in United States v. Wong Kim Ark (v.i.):

All persons born in the allegiance of the king are natural-born subjects, and all persons born in the allegiance of the United States are natural-born citizens. Birth and allegiance go together. Such is the rule of the common law, and it is the common law of this country… since as before the Revolution.

- ↑ However, in Minor v. Happersett the Supreme Court stated that there were doubts that a child is a natural born citizen, if he is born on U.S. territory of foreign parents (Minor v. Happersett, 88 U.S. 162, 1874):

The Constitution does not, in words, say who shall be natural-born citizens. Resort must be had elsewhere to ascertain that. At common-law, with the nomenclature of which the framers of the Constitution were familiar, it was never doubted that all children born in a country of parents who were its citizens became themselves, upon their birth, citizens also. These were natives, or natural-born citizens, as distinguished from aliens or foreigners. Some authorities go further and include as citizens children born within the jurisdiction without reference to the citizenship of their parents. As to this class there have been doubts, but never as to the first.

- ↑ Cf. Lyman Trumbull & Jacob M. Howard in: Congressional Globe, 1st Session, 39th Congress, pt. 4, pp. 2893–95:

Cf. the ruling in 14 Op. U.S. Attorney General, 300:The provision is, that 'all persons born in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens.' That means 'subject to the complete jurisdiction thereof.' What do we mean by 'complete jurisdiction thereof?' Not owing allegiance to anybody else. That is what it means.

The word “jurisdiction” must be understood to mean absolute and complete jurisdiction, such as the United States had over its citizens before the adoption of this amendment… Aliens, among whom are persons born here and naturalized abroad, dwelling or being in this country, are subject to the jurisdiction of the United States only to a limited extent. Political and military rights and duties do not pertain to them.

- ↑ United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649 (1898).

- ↑ Justice Gray distinguished between natural born citizens and citizens like Wong Kim Ark:

The foregoing considerations and authorities irresistibly lead us to these conclusions: The fourteenth amendment affirms the ancient and fundamental rule of citizenship by birth within the territory, in the allegiance and under the protection of the country, including all children here born of resident aliens… Every citizen or subject of another country, while domiciled here, is within the allegiance and the protection, and consequently subject to the jurisdiction, of the United States. His allegiance to the United States is direct and immediate… and his child, as said by Mr. Binney in his essay before quoted, 'If born in the country, is as much a citizen as the natural-born child of a citizen…'

- ↑ Arthur P. Hinman, Letter to the Editor: "Is Mr. Chester Arthur an Irishman by Birth?", Brooklyn Eagle, 08-11-1880, reprinted in: "Revived. The Question of President Arthur's Birthplace", in: Brooklyn Eagle, 09-21-1881, p. 2; Hinman's claims were known nation-wide due to several publications including e.g. the New York Tribune and The New York Times in June 1881.

- ↑ "Is Mr. Chester A. Arthur a Native Born Citizen?", in: Brooklyn Eagle, 08-13-1880, p. 2.

- ↑ Thomas C. Reeves, Gentleman Boss. The Life and Times of Chester Alan Arthur, Newtown 1991, p. 202 sq.

- ↑ "Eligible. Mr. Chester A. Arthur to the Office of Vice President", in: Brooklyn Eagle, 08-15-1880, p. 4.

- ↑ Arthur Hinman, "The Contest: Mr. Hinman Replies to General Arthur", in: Brooklyn Eagle, 08-19-1880, p. 4.

- ↑ Thomas C. Reeves, Gentleman Boss. The Life and Times of Chester Alan Arthur, Newtown 1991, p. 5; Reeves however assumes that the one-year change from 1829 to 1830 was made out of vanity.

- ↑ E.g. in "The Ex-President's Life. How Chester Alan Arthur Became Famous, The New York Times, 11-19-1886

- ↑ Miriam A. Drake, Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science: Lib-Pub, New York 2003, p. 2365; cp. Chester A. Arthur III, personal letter, in: The Chester A. Arthur Papers, Introduction to the Index, Library of Congress, Washington, p. i:

You may be sure that I am as interested as you are in having the Arthur papers finally come to rest in the Library of Congress. The ones that I have in my possession have traveled a good deal—over to Europe, back to Colorado, California, and now here. During his lifetime, my father would never let anyone see them—not even me. When they finally came into my possession I was amazed that there were so few… Charles E. McElroy, the son of Mary Arthur McElroy who was my grandfather’s First Lady, tells me that the day before he died, my grandfather caused to be burned three large garbage cans, each at least four feet high, full of papers which I am sure would have thrown much light on history.

- ↑ Cf. The Chester A. Arthur Papers, Introduction to the Index, Library of Congress, Washington:

For many years President Arthur was represented in the Manuscript Division by a single document… Beginning in 1910 and continuing to the present, successive chiefs of the division have done what they could do to assemble surviving Arthur manuscripts. For the first of these chiefs, Gaillard Hunt, who in that year intitiated the search for the main body of Arthur Papers, there was little but discouragement as a result of his inquiries. However, his persistence and what he was able to learn were to encourage his successors. He wrote first to Col. William G. Rice and learned the address of Mrs. John E. McElroy, Arthur’s sister and official hostess during his administration. Mr. Hunt wrote to her and learned from her that Chester A. Arthur, Jr., controlled the papers. After several attempts, Mr. Hunt learned Mr. Arthur’s address and wrote to him. The reply—written on March 13, 1915, five years after the search began—provided the first concrete but frustrating evidence:

"I beg you will excuse my tardiness in replying to your letter of November 4th [1914]. The question of my father’s papers is a very sore subject with me. These papers were supposed to be in certain chests which were stored on their receipt from Washington, in the cellar of 123 Lexington Avenue. After my father’s death, they were removed, I believe, by direction of the executors to a store house recommended by Mr. McElroy at Albany. Several years ago on making my residence in Colorado, I sent for these chests of papers and found in them nothing but custom house records of no particular value or importance. Where the papers they were supposed to contain have vanished, is a mystery."

Parts of this article were sourced originally from Biography of Chester Arthur, White House, accessed January 6, 2008.