Cricket (sport)

It will be evident by reading this article that cricket has a rich vocabulary. For an explanation of many of the terms used in this article, including those bold highlighted, see Glossary of cricket.

Cricket is defined by major dictionaries as an outdoor bat-and-ball game played by two teams of eleven players on a large grassy field, at the centre of which is a rectangular pitch with a wooden structure called a wicket sited at each end.[1][2] As in other sports, there are separate men's and women's versions, both played internationally. A match is divided into phases known as innings (same spelling for singular and plural) and, depending on the type of match, there may be two or four innings. In each innings, one team is batting and the other is fielding. Who bats first is decided by the toss of a coin before the match begins. Throughout an innings, all eleven members of the fielding team are usually on the field, but only two batsmen. The teams change roles between innings, the fielding team becoming the batting team and so playing its innings.

In all levels of cricket, the essence of the game is that the wicket is a target being attacked by a bowler on the fielding side and defended by a batsman on the batting side. The object of the batting team is to score as many runs as possible while an innings lasts. The object of the fielding team is to restrict scoring and dismiss the batsmen. Generally, the winning team is the one scoring the most runs, although a match can result in a draw. Adjudication is performed on-field by two umpires. Off the field, the match details including runs and dismissals are recorded by scorers. In televised matches, particularly those played at international level, there is often a "third umpire" who can make decisions on certain incidents with the aid of video evidence.

Cricket was probably created as a children's game in south-east England by the mid-sixteenth century and had become a major men's sport across southern England by the end of the seventeenth century. Women's cricket is first recorded in the mid-eighteenth century but gained no real significance until the twentieth century. With the expansion of the British Empire, cricket became widespread and is now the national summer sport in several English-speaking countries. Matches range in scale from informal weekend afternoon games played on village greens to top-level international contests played by professionals in modern, all-seater stadiums. Globally, the sport has a high level of player participation and is, second only to association football, one of the world's most popular spectator sports. As such, it attracts considerable media attention. Rules of play are encoded in the Laws of Cricket, copyright of which is owned by Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC), based at Lord's in north London. MCC was formerly the sport's governing body and still has responsibility for drafting and publishing the Laws. Governance now rests with the International Cricket Council (ICC) which has over 100 member countries.

Origin and development of cricket

According to the former British Prime Minister John Major in his book entitled More Than A Game, cricket is "a club striking a ball (like) the ancient games of club-ball, stool-ball, trap-ball, stob-ball". As he says, each of these have at times been described as "early cricket".[3] It is generally believed that cricket began as a children's game in the south-eastern counties of England sometime before the sixteenth century.[4]

The earliest definite mention of the sport in written records is dated Monday, 17 January 1597 (a Julian date which converts to Tuesday, 27 January 1598 in the Gregorian calendar).[5] John Derrick (born c.1538, probably at Guildford; date of death unknown) was a Queen's Coroner for the county of Surrey. He made a legal deposition that includes the earliest definite reference to cricket being played anywhere in the world and confirms that the game was played by children c.1550.[6]

Cricket had become an adult game by the early seventeenth century and the oldest known organised match took place c.1610 between two Kent village teams.[4] Village cricket became popular throughout south-east England and it is believed that the first professional players were hired by wealthy patrons sometime after the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660.[7] Patronage and gambling financed the sport into the eighteenth century[8] and, by the time of the Napoleonic Wars, it was being played nationwide in England and had been introduced to British colonies overseas.[9][10] Cricket was England's national sport in the nineteenth century when the first county clubs were founded and international matches began. It has continued to grow both domestically and internationally through the twentieth and 21st centuries. For commercial reasons, limited overs cricket began in the 1960s as an alternative to first-class cricket from the idea of a match being completed in a single day with a result guaranteed.[11] Cricket's global spread is directly attributable to the British Empire and it is generally viewed as the quintessential English sport that followed British colonists, traders and military expeditions everywhere. It has been said of cricket that it "was the umbilical cord of Empire linking the mother country with her children".[12]

Cricket has a rich literature beginning with John Nyren in the 1830s and continuing via the works of Neville Cardus, C. L. R. James, John Arlott and others, but the doyen of cricket literature is Wisden Cricketers' Almanack, first published in 1864 by John Wisden, who was an outstanding player of the time. Beginning in 1889, Wisden has run an annual award for outstanding achievements in the previous English season called the "Cricketers of the Year". Generally, five players are named and, subject to certain rare exceptions, no one can receive the award more than once.[13]

Cricket in the 21st century has high player participation with numerous minor competitions at all age levels widespread in every country in which it is played. With an estimated 2.5 billion fans, it is one of the world's greatest spectator sports, second only to football.[14] As a result, it has considerable social and cultural influence and attracts massive media coverage. The Twenty20 variant of limited overs has been a huge success, especially the Indian Premier League.[15] Test cricket remains the top level of international cricket and ICC full membership is eagerly sought.[16]

A significant feature of 21st century cricket has been the growth in popularity and prestige of the women's game which, as in other sports, is administered separately from the men's game but with strong interactivity.[17] In 1998, control of women's cricket was transferred from the Women's Cricket Association, founded in 1926, to the England and Wales Cricket Board (ECB).[18] The stature of women's cricket was fully recognised in the 2009 edition of Wisden when, for the first time, a woman was one of the five cricketers of the year. In 2018, no less than three women were among the five.[19]

The game of cricket and its objectives

Basics

A cricket match is played between two teams (or sides) of eleven players each on a grassy field of variable size and shape. Field diameters of 150–160 yards are usual.[20] The perimeter of the field is known as the boundary and this is often marked out by means of a rope that is laid on the ground to encircle the edge of the field with spectator seating beyond.[21] The field may be round, square or oval – many venues worldwide are known as "Oval" including Kennington Oval in south London, the Adelaide Oval in South Australia and Kensington Oval in Bridgetown, Barbados. Most of the action takes place in a specially prepared area of the field (generally in the centre) that is called the pitch and is rectangular, 22 yards long by ten feet wide.[22] The wickets are sited at each end of the pitch. A wicket, made entirely of wood (usually polished ash), consists of three upright stumps topped by two horizontal bails. Each wicket is 28 inches high by nine inches wide.[23]

Before play commences, the two team captains meet on the pitch and toss a coin to decide which team shall bat or field first.[24] The captain who wins the toss makes his decision on the basis of tactical considerations including the current and expected pitch and weather conditions. Cricket is an intensely strategic sport and the captain is the most important member of the team as he bears responsibility for leadership and team tactics, especially when his team are fielding, though he will tend to consult other senior players before making any tactical decision. The captain is usually the most experienced member of the team.[25]

In normal circumstances, there are fifteen people on the field while a match is in play. They are the two umpires, who regulate all on-field activity, all eleven members of the fielding team and two members of the batting team, who are called the batsmen. The other nine members of the batting team are off the field in the pavilion. The fielding team is allowed substitutes in case of injury or other valid reasons for a player's absence, subject to Law 24 which stipulates that a substitute is not allowed for a fielder who leaves for other than a "wholly acceptable reason".[26] One of the fielding team is the wicket-keeper, who is a specialist. The wickets serve as targets for the bowlers on the fielding side and are defended by the batsmen who seek to accumulate runs. The fielding side seeks to dismiss the batsmen by various means until the batting side is "all out", whereupon the innings is complete and the teams reverse roles for the next innings.[27]

Any of the eleven fielders can bowl but normally it is the four or five recognised as skilled bowlers who do most of the bowling. It is extremely rare, though not unknown, for the wicket-keeper to bowl. Most of the remaining fielders are in the team as specialist batsmen and are unlikely to bowl, but a team often includes one or two all-rounders, who are good at both batting and bowling. The wicket-keeper operates behind the stumps being attacked by the bowler. Apart from these two, the fielders are tactically deployed in various places across the whole field of play, except as stipulated in Law 28.5 that they are not allowed to stand on the pitch.[28] The two batsmen take up position at either end of the pitch. The one facing the bowler, and defending the wicket being attacked, is called the "striker". His partner, the "non-striker", stands near the other wicket at the bowler's end of the pitch. One of the umpires stands behind the wicket at the bowler's end and the other stands in a position called "square leg", which is about fifteen yards from the striker and in direct line with his wicket.[29]

Pitch, wickets and creases

The pitch is 22 yards long (the length of an agricultural chain) between the wickets and is 10 feet wide.[22] It is a flat surface and has very short grass that tends to be worn away as the game progresses. The condition of the pitch has a significant bearing on the match and team tactics are always determined with the state of the pitch, both current and anticipated, as a deciding factor.[20] Each wicket consists of three wooden stumps placed in a straight line and surmounted by two wooden bails placed across the two gaps; the total height of the wicket including bails is 28.5 inches and the combined width of the three stumps is 9 inches.[23]

Four white lines, known as creases, are painted onto the pitch around each of the wicket areas to define the batsman's "safe territory" and to determine the limit of the bowler's approach. These are called the "popping" (or batting) crease, the bowling crease and two "return" creases. The stumps are placed in line on the bowling creases, which mark the ends of the pitch, and so these must be 22 yards apart.[30]

The bowling crease, a misnomer as it has nothing to do with bowling any more, is 8 feet 8 inches long with the middle stump placed dead centre.[30] The popping crease is parallel to the bowling crease and is four feet in front of the wicket. It is drawn to the length of twelve feet but is in fact unlimited in its length.[30] The return creases are perpendicular to the other two; they are adjoined to the ends of the popping crease and are drawn through the ends of the bowling crease to a length of at least eight feet behind the popping crease but, again, are actually unlimited in length.[30]

When bowling the ball, the bowler's back foot in his "delivery stride" must land within the two return creases while his front foot must land on or behind the popping crease. If he breaks this rule, the umpire calls a "no ball" and the fielding team are penalised by the addition of one "extra" to the batting team's score; in addition, the delivery being null and void, it must be bowled again.[31] The batsman stands on or close to the popping crease at his end when facing the bowler but its real importance to him is that it marks the limit of his safe territory and he can be "stumped" or "run out" (two common forms of dismissal) if the wicket is broken while he is "out of his ground" (i.e., forward of the popping crease).[29]

Bat and ball

The act of bowling is the delivery by the bowler of the ball from his end of the pitch to the other, where the wicket is defended by the striker, armed with a bat. The bat is made of wood (usually willow) and takes the shape of a straight blade topped by a cylindrical handle. The blade must not be more than 4.25 inches wide and the total length of the bat not more than 38 inches.[32]

The ball is a rock-hard leather-seamed spheroid projectile with a circumference limit of 9 inches.[33] It can be delivered by the fastest bowlers at speeds of more than 90 mph and so the batsmen and the wicket-keeper wear protective gear. Batsmen wear pads (designed to protect the knees and shins), reinforced batting gloves, a safety helmet and a box. Some batsmen wear additional padding inside their shirts and trousers such as thigh pads, arm pads, rib protectors and shoulder pads. The wicket-keeper wears pads and specially reinforced gauntlets to protect his legs and hands respectively.[34]

The bowler must complete the delivery with a straight arm and must ensure that he keeps his feet within bounds set by the creases, as described above. The bowler delivers six balls (deliveries) in turn towards the same wicket to complete an over, so-called because the umpire at the bowler's end calls "Over!" when six balls have been bowled. If the bowler does not concede any runs in the over, that over is termed a maiden and the bowler is credited with these in his career statistics. When the over is complete, the fielding side changes ends and a different bowler takes the ball to bowl an over to the wicket at the opposite end. The batsmen do not change ends at the end of an over so the one who was the non-striker becomes the striker for the start of the new over. The umpires change places between overs. Bowlers tend to operate in pairs so the same two are likely to alternate through several overs before the captain decides to introduce one or two new bowlers.[35]

If the delivery hits and breaks the wicket, the striker is ruled to be out because he has been "bowled".[36] He must then leave the field and another batsman replaces him. The non-striker stays in place. As there are several means of dismissal, the bowler does not necessarily bowl at the wicket because he may try to deceive the striker into playing a poor shot, which could result in another form of dismissal. The most common one is "caught", after the ball has made contact with the bat and been caught on the full by one of the fielders.[37]

The batting team's captain can declare the innings closed at any time for tactical reasons but it is always the case that the innings is terminated if ten of the batsmen are out. One batsman remains not out but there must always be two batsmen "in" so his innings ends when he loses his last partner.[38]

Fielding

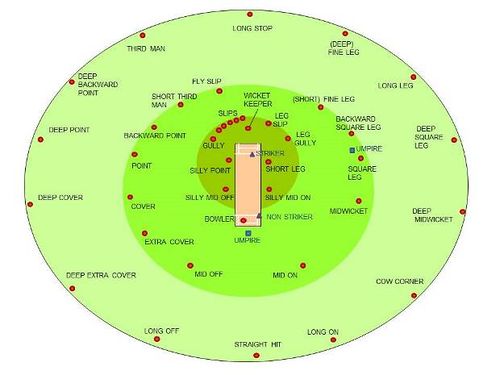

All eleven players on the fielding side take the field together.[28] One of them is the wicketkeeper who operates behind the wicket being defended by the batsman on strike.[39] Besides the one currently bowling, the other fielders are tactically deployed by the team captain in chosen positions around the field. These positions are not fixed but they are known by specific and sometimes colourful names such as "slip", "third man", "silly mid on" and "long leg". The captain is the most important member of the fielding side as he determines all the tactics including who should bowl (and how); and he is responsible for "setting the field", though usually in consultation with the bowler.[40]

Bowling

All bowlers are classified according to their pace or style. The classifications, as with much cricket terminology, can be very confusing. Hence, a bowler could be classified as LF, meaning he is a left arm fast bowler; or as LBG, meaning he is a right arm spin bowler who bowls deliveries that are called a leg break and a googly.[41] The bowler reaches his delivery stride by taking a run-up to gain momentum.[42]

A fast bowler takes quite a long run-up, running very fast as he does so. Bowlers with a very slow delivery take no more than a couple of steps before bowling. The fastest bowlers can deliver the ball at a speed of over 90 mph and they usually rely on sheer speed to try and defeat the batsman, who is forced to react very quickly to a ball that reaches him in an instant. The generally accepted world record for the fastest recorded delivery of a cricket ball is 100.23 mph by Shoaib Akhtar at Cape Town's Newlands Cricket Ground in February 2003.[43] Other fast bowlers rely on a mixture of speed and guile. Some fast bowlers make use of the seam of the ball so that it "curves" or "swings" in flight and this type of delivery can deceive a batsman into mistiming his shot so that the ball touches the edge of the bat and can then be "caught behind" by the wicket-keeper or a slip fielder.[44] At the other end of the bowling scale is the spinner who bowls at a relatively slow pace and, with the spin he imparts onto the ball, relies entirely on guile to deceive the batsman. A spinner will often "buy his wicket" by "tossing one up" to lure the batsman into making an adventurous shot. The batsman has to be very wary of such deliveries as they are often "flighted" or spun so that the ball will not behave quite as he expects and he could be trapped into getting himself out.[45] In between the pacemen and the spinners are the "medium pacers" who rely on persistent accuracy to try and contain the rate of scoring and wear down the batsman's concentration. These bowlers are classified by arm as LM or RM.[41]

Batting

At any one time, there are two batsmen in the playing area. One takes station at the striker's end to defend the wicket as above and to score runs if possible. His partner, the non-striker, stands at the end where the bowler is operating.[46] Depending on the quality of the delivery he receives, the striker may play defensively without attempting to score a run. If he plays an offensive shot to hit the ball away from the pitch and directed clear of the fielders, then he and his partner can run the length of the pitch to complete a run which is the means of scoring in cricket. Each run is added to the team total and to the striker's personal total.[47]

A skilled batsman can use a wide array of "shots" or "strokes" in both defensive and attacking mode. Cricket is very fond of naming things, as with the field placings, and each shot or stroke in the batsman's repertoire has a name too: e.g., "cut", "drive", "hook", "pull", etc. The idea is to hit the ball to best effect with the flat surface of the bat's blade. Batsmen do not always seek to hit the ball as hard as possible and a good player can score runs just by making a deft stroke with a turn of the wrists or by simply "blocking" the ball but directing it away from fielders so that he has time to take a run.[48][49]

A batsman does not have to play a shot and can "leave" the ball to go through to the wicketkeeper, providing he thinks it will not hit his wicket. Equally, he does not have to attempt a run when he hits the ball with his bat. He can deliberately use his leg to block the ball and thereby "pad it away" but this is risky because of the "leg before wicket (lbw)" rule. If a batsman "retires" (usually due to injury) and cannot return, he is actually "not out" and his retirement does not count as a dismissal, though in effect he has been dismissed because his innings is over. Substitute batsmen are not allowed, although substitute fielders are.[46]

Runs

The primary concern of the batsman on strike (i.e., the "striker") is to prevent the ball hitting the wicket and secondarily to score runs by hitting the ball so that he and his partner have time to run from one end of the pitch to the other before the fielding side can return it. Each completed run increments the score. More than one run can be scored from a single hit but, while hits worth one to three runs are common, the size of the field is such that it is usually difficult to run four or more. To compensate for this, hits that reach the boundary of the field are automatically awarded four runs if the ball touches the ground en route to the boundary or six runs if the ball clears the boundary on the full. Hits for five are unusual and generally rely on the help of "overthrows" by a fielder returning the ball. If an odd number of runs is scored by the striker, the two batsmen have changed ends and the one who was non-striker is now the striker. Only the striker can score individual runs but all runs are added to the team's total.[47]

Extras

Additional runs can be gained by the batting team as "extras" or "sundries" by courtesy of the fielding side. This is achieved in four ways:

- No ball – a penalty of one extra that is conceded by the bowler if he breaks the rules of bowling either by (a) using an inappropriate arm action; (b) overstepping the popping crease; (c) having a foot outside the return crease.[31]

- Wide – a penalty of one extra that is conceded by the bowler if he bowls so that the ball is out of the batsman's reach.[50]

- Bye – extra(s) awarded if the batsman makes no contact with the ball and it goes past the wicket-keeper to give the batsmen time to run in the conventional way.[51]

- Leg bye – extra(s) awarded if the batsman does not hit the ball with his bat or his hand holding the bat but it strikes another part of his body (not just his leg) and goes away from the fielders to give the batsmen time to run in the conventional way.[51]

When the bowler has bowled a no ball or a wide, his team incurs an additional penalty because that ball (i.e., delivery) has to be bowled again and hence the batting side has the opportunity to score more runs from this extra ball.[31][50] The batsmen have to run (i.e., unless the ball goes to the boundary for four) to claim byes and leg byes but these only count towards the team total, and to the extras, not to the striker's individual total for which runs must be scored off the bat.[51] For a leg bye to count, the umpire must be satisfied that the batsman tried to play a shot or that he was trying to avoid being struck by the ball.[51]

Dismissals

There are several ways in which a batsman can be dismissed and some are so unusual that only a few instances of them exist in the whole history of the game. The most common forms of dismissal are "bowled", "caught", "leg before wicket" (lbw), "run out", "stumped" and "hit wicket". The unusual methods are "hit the ball twice", "obstructed the field", and "timed out".

Before the umpire will award a dismissal and declare the batsman to be out, a member of the fielding side (generally the bowler) must appeal.[52] This is invariably done by asking (or shouting) the term "Owzat?" which means, simply enough, "How is that?" If the umpire agrees with the appeal, he will raise a forefinger and say: "Out!" Otherwise he will shake his head and say: "Not out".[52] Appeals are particularly loud when the circumstances of the claimed dismissal are unclear, as is always the case with lbw and often with run outs and stumpings. It is usually the striker who is out when a dismissal occurs but the non-striker can be dismissed by being run out.

- Bowled – the bowler has hit the wicket with the ball and the wicket has "broken" with at least one bail being dislodged (if the ball hits the wicket without dislodging a bail, the batsman is not out).[36]

- Caught – the batsman has hit the ball with his bat or with his hand holding the bat and the ball has been caught on the full by a member of the fielding side.[37]

- Leg before wicket (lbw) – is complex but basically means that the batsman would have been bowled if the ball had not hit his leg first.[53]

- Run out – a fielder has broken the wicket with the ball while a batsman was out of his ground; this usually occurs by means of an accurate throw to the wicket while the batsmen are attempting a run.[54]

- Stumped – the wicket-keeper has broken the wicket with the ball in his hand after the batsman has stepped out of his ground without attempting a run.[55]

- Hit wicket – means simply that a batsman did just that, often by hitting the wicket with his bat or by falling onto it.[56]

- Hit the ball twice – is very unusual and was introduced as a safety measure to counter dangerous play and protect the fielders.[57]

- Obstructing the field – another unusual dismissal which tends to involve a batsman deliberately getting in the way of a fielder; this has now been revised to include the former offence of "handled the ball".[58]

- Timed out – usually means that the next batsman did not arrive at the wicket within two minutes of the previous one being dismissed.[59]

Types of match and competition

Cricket is a multi-faceted sport whose Laws allow for many variations of contest and competition according to duration, location, timing, playing standards, qualification and other factors. In very broad terms, cricket can be divided into matches in which the teams have two innings apiece and those in which they have a single innings each. The former has a duration of three to five days (in earlier times there were "timeless" matches too); the best-known form of the latter, known as limited overs cricket (or "one-day cricket") because each team bowls a limit of typically 50 overs, has a planned duration of one day only (a match can be extended if necessary due to bad weather, etc.). Historically, a form of cricket known as single wicket was extremely popular and many of these contests in the 18th and 19th centuries qualify as top-class matches. Single wicket has rarely been played since limited overs cricket began.

Test cricket

Test cricket is the highest standard of cricket. A Test match is an international fixture, invariably part of a "series" of three to five games, between two national teams that have "full member" status within the ICC.[60] The teams have two innings each and the match lasts for up to five days with a scheduled six hours of play on each day (this varies if there are interruptions due to the weather or if an agreed number of overs is not completed within the six hours). Men's Test cricket began with Australia versus England in 1877, although the early Tests were in fact classified as such retrospectively.[61] Women's Test cricket began in 1934, again with Australia Women hosting England Women.[18]

Subsequently, ten other countries have achieved men's Test status: South Africa (1889), West Indies (1928), New Zealand (1929), India (1932), Pakistan (1952), Sri Lanka (1982), Zimbabwe (1992), Bangladesh (2000), Afghanistan (2018) and Ireland (2018). The West Indies is a federation whose team is made up of players from nations including Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica, and Trinidad & Tobago. England is actually England and Wales combined; similarly Ireland is a combination of the two Irish countries. In women's cricket, the teams that have played Test matches are Australia Women, England Women, India Women, Netherlands Women, New Zealand Women, South Africa Women and West Indies Women.

First-class cricket

Test cricket is a form of first-class cricket. This form, which has an official definition, is generally used in reference to the highest level of domestic cricket, especially in the Test-playing nations. National championships, such as the English and Welsh County Championship, are first-class competitions. A first-class match has a duration of three to five days, the teams having two innings each.[62]

The draw is a possible result in first-class matches and this happens if playing time expires while the losing team is still batting (in other words, if the team batting last have not reached their target total and are not all out when time is up).[63] Another feature of first-class matches is the follow-on, whereby the team batting second can be asked by the fielding captain to bat again in the third innings if they have been dismissed for a total that is over 150 less (200 less in a Test) than the first innings score of their opponents. This, in turn, can lead to an innings defeat if the team following on are all out for another low score and the combined totals of their two innings is less than that scored by their opponents in one innings.[64]

Limited overs

A Limited Overs International (LOI) is the highest standard of limited overs cricket. In men's cricket, as well as the countries that play Test matches, this class includes those that have ICC associate member status, although they rarely play against the Test teams.[65] Prominent associate members are Argentina, Bermuda, Canada, Kenya, Namibia, Netherlands, Scotland and the United States. The Women's Cricket World Cup was inaugurated in 1973 and the Men's Cricket World Cup in 1975. Women's teams playing in LOIs in addition to the seven Test countries are Bangladesh Women, Pakistan Women and Sri Lanka Women.

Limited overs matches are scheduled for a single day but they can be extended if necessary due to bad weather. Each team has one innings and the overs limit is usually fifty per side. There are various competitions in domestic cricket, beginning in England with the Gillette Cup knockout in 1963. There is no draw result except in the form of a tie, when the scores are level, or a "no result" due to rain or other factors.[66]

Twenty20

Twenty20 is a variant of limited overs in which each team has twenty overs. The match lasts two to three hours and so can be fitted into an evening. Twenty20 was introduced into English cricket in 2003 and has become extremely popular in India where the Indian Premier League is contested.[15] The Twenty20 International (T20I) was soon introduced and there is a Men's ICC World Twenty20 Championship, first held in 2007[67] and a Women's ICC World Twenty20 Championship, first held in 2009.[68]

National championships

These are held in each country and are the main examples of first-class cricket. For example, England has the County Championship which has tentative origins stretching back to 1728 and was formally organised as an official competition in 1890. Since 2000, this involves 18 county clubs who are split into two divisions.[69] Each team plays the other eight in its division both home and away in double innings fixtures with a duration of up to four days. The oldest county club is Sussex, founded in 1839. The most successful club is Yorkshire, who have won the title outright on 32 occasions, most recently in 2014 and 2015.[69]

All the other Test countries have a similar setup. Australia's national championship involves the various state sides playing for the Sheffield Shield; in India, the championship is the Ranji Trophy; in South Africa, the Currie Cup; and so on. Women's national championships take place in a number of countries; for example, the one in England is a 50-over limited overs competition involving sixteen county teams.

Minor cricket

Below the national championship level in each country there are various leagues, often organised on a state, county or regional basis, that include clubs which are classed as "minor" although in many cases the playing standards are anything but minor. Again using England as an example, the main minor competition is the Minor Counties Championship which began in 1895 and includes 20 county clubs that are not qualified for the County Championship, although it is possible for a "minor county" to achieve this qualification. The last to do so was Durham in 1992.[70]

Below that level are numerous regional leagues which involve town and village clubs whose players are generally local residents. These tend to play at weekends only. Some of the leagues are notable for high standards, especially as professionals have frequently been employed. For example, the great Gary Sobers played for Radcliffe Cricket Club in the Central Lancashire League for several seasons around 1960. Other notable leagues in England are the Lancashire League and the Bradford League.[71]

Schools cricket has always been very important for giving youngsters an introduction to the skills of the sport and this has always been most effective where good quality coaching has been available.[72]

Other types of cricket

In domestic competitions, limited-overs games of differing lengths are played. There are also numerous informal variations of the sport played throughout the world that include indoor cricket, French cricket,[73] beach cricket, "Kwik" cricket[74] and all sorts of card games and board games that have been inspired by cricket.

Notes

- ↑ Chambers, page 357.

- ↑ Oxford, page 338.

- ↑ Major, page 17.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Underdown, page 4.

- ↑ Major, page 19.

- ↑ Altham, page 21.

- ↑ Webber, page 10.

- ↑ Birley, pages 14 to 16.

- ↑ Haygarth, page vi.

- ↑ Bowen, pages 261 to 267.

- ↑ Birley, pages 293 to 294.

- ↑ Kaufman, Jason & Patterson, Orlando: Cross-National Cultural Diffusion: The Global Spread of Cricket. American Sociological Review, Harvard University (2005).

- ↑ Wisden Almanack 1896. ESPN Sports Media Ltd (2018).

- ↑ Top 10 List of the World's Most Popular Sports. Top End Sports Network (2018).

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 What makes the IPL successful? ESPN Sports Media Ltd (2018).

- ↑ Ireland & Afghanistan awarded Test status by International Cricket Council. BBC Sport (2017).

- ↑ 21st century cricket. ICC, History of Cricket (2018).

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Women's Cricket History. Women's Cricket Associates (2018).

- ↑ Three women among Wisden's Five Cricketers of the Year. ESPN Sports Media Ltd (2018).

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 How Big is a Cricket Field? Dimensions Info (2018).

- ↑ This brings to mind arguably the greatest book in cricket's vast pantheon of literature: Beyond A Boundary by the radical Trinidadian writer, C. L. R. James.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Law 6 – The Pitch. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Law 8 – The Wickets. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ Law 13.4 – The Toss. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ Brearley, Mike: The Art of Captaincy, 285 pages. Channel Four Books (1985).

- ↑ Law 24 – Fielders Absence and Substitutes. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ Law 13.3 – Completed Innings. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Law 28 – The Fielder. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Law 30 – Batsman out of ground. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 Law 7 – The Creases. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Law 21 – No ball. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ Law 5 – The Bat. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ Law 4 – The Ball. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ Cricket equipment guide. BBC Sport (2018).

- ↑ Law 17 – The over. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Law 32 – Bowled. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Law 33 – Caught. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ Law 15 – Declaration and forfeiture. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ Law 27 – The Wicket-keeper. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ How to set a field. BBC Sport (2018).

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Playfair 2018, page 86.

- ↑ Oxford, page 1260.

- ↑ Fastest delivery of a cricket ball. Guinness World Records Limited (2018).

- ↑ The science of swing bowling. ESPN Sports Media Ltd (2018).

- ↑ Spin bowling (from Wisden 1938). ESPN Sports Media Ltd (2018).

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Law 25 – Batsmen's innings. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Law 18 – Scoring runs. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ Batting basics. BBC Sport (2009).

- ↑ Different strokes. ESPN Sports Media Ltd (2011).

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Law 22 – Wide ball. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 51.3 Law 23 – Bye and leg bye. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Law 31 – Appeals. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ Law 36 – Leg before wicket (lbw). MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ Law 38 – Run out. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ Law 39 – Stumped. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ Law 35 – Hit wicket. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ Law 34 – Hit the ball twice. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ Law 37 – Obstructing the field. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ Law 40 – Timed out. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ Barclay's, page 700.

- ↑ Birley, page 123.

- ↑ Barclay's, page 695.

- ↑ Law 16 – The result. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ Law 14 – The follow-on. MCC, Laws of Cricket (2017).

- ↑ ICC Associate and Affiliate Members ESPN Sports Media Ltd (2018).

- ↑ Barclay's, pages 495 to 496.

- ↑ Toast the success. ESPN Sports Media Ltd (2007).

- ↑ ICC Women's World Twenty20, 2009. ESPN Sports Media Ltd (2009).

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Playfair 2018, page 220.

- ↑ Playfair 2018, page 94.

- ↑ Birley, page 152.

- ↑ Altham, pages 66 to 68.

- ↑ French Cricket. Top End Sports Network (2018).

- ↑ Kwik Cricket. Lancashire Cricket (2018).

Bibliography

- Altham, H. S.: A History of Cricket, Volume 1 (to 1914). George Allen & Unwin (1962).

- Arlott, John: Arlott on Cricket. Collins (1984).

- Birley, Derek: A Social History of English Cricket. Aurum (1999).

- Bowen, Rowland: Cricket: A History of its Growth and Development. Eyre & Spottiswoode (1970).

- Haygarth, Arthur: Scores & Biographies, Volume 1 (1744-1826). Lillywhite (1862).

- International Cricket Conference (ICC): Official ICC App. ICC (2018).

- Major, John: More Than A Game. HarperCollins (2007).

- Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC): Laws of Cricket. MCC (2017).

- Oxford University: Oxford English Dictionary, 11th Edition. Oxford University Press (2004).

- Playfair: Playfair Cricket Annual 2018 (editor Ian Marshall). Headline Publishing Group (2018).

- Underdown, David: Start of Play. Allen Lane. (2000).

- Webber, Roy: The Phoenix History of Cricket. Phoenix (1960).

- Wisden: Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. John Wisden & Co. Ltd (1864 to present).