Federal Reserve System

The Federal Reserve System is the central bank of The United States. It is also known as The Federal Reserve, or more informally as The Fed. The current leader of the Federal Reserve System is Ben Bernanke, the chairman of the Board of Governors

Organization

The Federal Reserve is an independent agency of the United States federal government. Congress has a supervising role, but does not interfere on a daily basis. The chairman of the Federal Reserve is reporting to Congress biannually, but it is usually working closer with The Department of the Treasury and the president. Even though The Fed has an independent status, its independence might be revoked by Congress if Congress wishes to.[1]

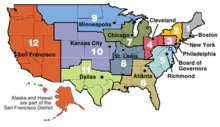

The Federal Reserve System is divided into twelve districts, each district having one central bank (called a Federal Reserve Bank). This unique system came as a compromise between those who wanted a strong, federal central bank and those who wanted to continue with the decentralized system in place before 1913.

The Board of Governors is administrating the system. The board is also responsible for the formulation of monetary policy, and for regulating the Federal Reserve Banks and U.S. commercial banks. The seven members of the board are appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. The terms span several presidential and congressional terms, so that the board is autonomous. The chairman serves four-year terms, and can be reappointed.

Congress is not funding the Federal Reserve, so that the Fed is free from political pressure. The Fed's main sources of income are the trade of government securities and the making of short term loans to depository institutions. After the Federal Reserve pays its expenses, the rest of the earnings are transferred to the Treasury. About 95 percent of the Reserve Banks' net earnings have been paid into the Treasury since the Federal Reserve System began operations in 1914. In 2003, the Federal Reserve paid approximately $22 billion to the Treasury. The member banks receive an annual dividend of 6 percent as specified by law. The Board of Governors conduct an audit of the Reserve Banks annually.[2]

An important part of the Fed is the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). The FOMC is responsible for buying and selling government securities, and is therefore controlling the money supply of the United States.

A commercial bank may be a member of the Federal Reserve. Such banks are called member banks. 3000 of America's 8000 banks are members. Nationally chartered banks are required to be members, but it is voluntary for state banks, upon meeting certain standards.[3]

History

Central banking in the U.S. before the Federal Reserve System

The first central bank in the United States was the First Bank of the United States, created by the Washington administration in 1791. The driving force behind its creation was Alexander Hamilton, while Thomas Jefferson opposed it. The bank was headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, with branches around the nation. The bank had a capital of 10 million, with the federal government owning 20%. The First Bank invested in government bonds, was the government's fiscal agent, and dealt in gold bullion and foreign exchange. The First Bank was also competing with private state banks, making them resent the competition. The First Bank's charter was not renewed in 1811, after the Democratic-Republican Party and president James Madison opposed it.[4]

The United States had no central bank during the War of 1812, and the federal government had to take loans from state banks. The notes from private banks were often traded at a discount, because of their excessive issue of money. The situation was so chaotic that the government had to charter a new central bank, called the Second Bank of the United States. This bank was created in 1816, and the federal government owned seven of its $35 million capital. The Second Bank's notes were made legal tender. The Second Bank was forced to help the state banks in cases of emergency, as a lender of last resort.

Commercial banks were opposed to the Second Bank just like they were to the First Bank. It was also opposed by farmers who wanted easy credit. The opposition made Andrew Jackson veto the renewal of its charter, so that is ceased to exist as a central bank in 1836.[5]

The founding of the Fed

During the first decades of the 20th century, the United States was the last major, industrialized country without a central bank. Strong forces in the financial community demanded a central bank, because of incidents like the Panic of 1907.

In 1908, a Congressional commission was established to come up with a solution. The debate was heated, as some politicians were afraid of giving too much power to the New York financial elite, while others were afraid of giving too wide powers to the federal government. Consensus was reached during the administration of Woodrow Wilson, when the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 was passed. The bill was proposed by democrats Carter Glass and Robert L. Owen, and was inspired by an earlier bill known as the Aldrich Bill. The House of Representatives passed the Fact by a vote of 298 to 60, while the Senate passed it by a vote of 43 to 25. Most bankers opposed the Federal Reserve System's creation, as they felt that the government had too much control over it.[6] The act was more popular among smaller banks in the west and among small businesses.

The Federal Reserve Banks

- 1st district: Federal Reserve Bank of Boston

- 2nd district: Federal Reserve Bank of New York

- 3rd district: Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia

- 4th district: Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland

- 5th district: Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond

- 6th district: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

- 7th district: Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago

- 8th district: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

- 9th district: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis

- 10th district: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City

- 11th district: Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas

- 12th district: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

What a Federal Reserve Bank does

Monetary Policy

The Federal Reserve Act of 1913 [7] requires the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and the Federal Open Market Committee to seek to "promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices and moderate long-term interest rates" [8].

Supervision and Regulation

The Governors of the Federal Reserve System are responsible for the supervision and regulation of member banks and of state-licensed agencies of foreign banks. The supervision and regulation of other banks is the responsibility of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation or of The Office of Thrift Supervision [9].

Further reading

see the longer guide at Federal Reserve System/Bibliography

- Epstein, Lita & Martin, Preston (2003). The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Federal Reserve. ISBN 0-02-864323-2. excerpt and text search

- Greenspan, Alan. The Age of Turbulence: Adventures in a New World (2007), memoirs covering his chairmanship 1987-2006 excerpt and text search

- Greider, William, Secrets of the Temple. (1987). ISBN 0-671-67556-7; nontechnical book explaining the structures, functions, and history of the Federal Reserve, focusing specifically on the tenure of Paul Volcker

- Hafer, R. W. The Federal Reserve System: An Encyclopedia. (2005). 451 pp, 280 entries; ISBN 4-313-32839-0.

- Hetzel, Robert L. The Monetary Policy of the Federal Reserve: A History (2008) from 1913 to 2007; excerpt and text search

- Treaster, Joseph B. Paul Volcker: The Making of a Financial Legend (2004), chairman 1979-87 online edition

- Tuccille, Jerome. Alan Shrugged: The Life and Times of Alan Greenspan, the World's Most Powerful Banker (2002) online edition

References

- ↑ Tucker, Irvin B (2006) Survey of Economics. Page 358. Thomson South-Western, Mason, OH. ISBN 032431972

- ↑ Fox, Lynn S. et al. (2005) The Federal Reserve System: Purposes and Functions. Page 19-20. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Washington, DC.

- ↑ Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas: Understanding the Fed

- ↑ Wells, Donald R. (2004) The Federal Reserve System: A History. Page 7. McFarland & Company, Jefferson, NC. ISBN 0-786-41880.

- ↑ Wells, page 7

- ↑ Flaherty, Edward. A Brief History of Central Banking in the United States - 13/13 Federal Reserve Act (1913).

- ↑ The Federal Reserve Act

- ↑ "The Federal Reserve System, Purposes and Functions" Chapter 2, The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

- ↑ "The Federal Reserve System, Purposes and Functions" Chapter 5, The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System