Moving panorama

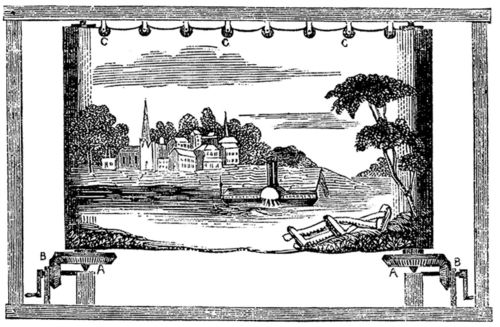

The Moving Panorama, so called, was a relative more in concept than design to the Panoramic painting, but proved to be more durable than its fixed and immense cousin. These paintings were not true panoramas, but rather contiguous views of passing scenery, as if seen from a boat or a train window. Installed on immense spools, they were scrolled past the audience behind a cut-out drop-scene or proscenium which hid the mechanism from public view. Unlike the Panoramic painting, the moving panorama almost always had a narrator, styled as its "Delineator" or "Professor", who described the scenes as they passed and added to the drama of the events depicted. One of the most successful of these delineators was John Banvard, whose panorama of a trip up (and down) the Mississippi River had such a sucessful world tour that the profits enabled him to build an immense mansion, lampooned as "Banvard's Folly", built in imitation of Windsor Castle in New Jersey. In Britain, showmen such as the durable Moses Gompertz toured the provinces with a variety of such panoramas well into the 1880's; when Gompertz retired, his former assistants the Poole brothers carried on the trade into the early part of the twentieth century using petrol-powered vans to transport their rolls.

Subject Matter

Moving panoramas were especially suited to the depiction of travel, as the scrolling of the canvas corresponded readily with the traverse of a linear landscape. In Great Britain in the 1850s, besides Banvard's Mississippi panorama, panoramas of voyages to New Zealand and the Holy Land were popular, as were depictions of the Overland Mail to India, which was the subject of no fewer than three moving panoramas. Voyages across the Atlantic were a perpetual subject, as were crossings of North America during the period immediately following the California Gold Rush. The Great Lakes framed a number of panoramas, including one, the Nine-Mile Mirror, which claimed to actually be nine miles in length (the weight of such a canvas would have prohibited its transport or easy display). One of the most durable subjects proved to be the exploration of the Arctic regions, which was the subject of no fewer than eight moving panoramas in the period 1849-1859 alone. Wars were always a popular subject; several panoramas in the 1850's depicted the Sepoy Rebellion in India, and the latter nineteenth century saw dozens of competing panoramas of the U.S. Civil War.

Popularity

At the peak of its success in the mid-nineteenth century, the moving panorama was quite possibly the most popular entertainment in the world, with hundreds of panoramas constantly touring the countryside. The smaller panoramas could be hauled by horse and wagon, and the expansion of railway service in Britain and the United States opened new markets to traveling panoramists. One typical such figure, Rufus C. Somerby, spent more than twenty years in the midwestern states showing panoramas managed by George K. Goodwin of Boston; he was the delineator and his wife played the piano. Mark Twain, in one of his humorous reminiscences, gives a fair idea of the audience for such panoramas in the latter part of the century:

Surving moving panoramas

Few moving panoramas have survived to this day, and conservation issues prevent them from being shown in their original format. The most notable rediscovered moving panorama in the United States is the Grand Moving Panorama of Pilgrim's Progress, which was discovered after having been forgotten in storage after nearly a century at the York Institute in Saco, Maine by Tom Hardiman. It was found to incorporate designs by many of the leading painters of its day, including Jasper Francis Cropsey, Frederic Edwin Church, and Henry Courtney Selous (Selous was the in-house painter for the original Barker panorama in London for many years). The Peabody-Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts Thomas F. Davidson's moving panorama of a Whaling Voyage (1860), and the New Bedford Whaling Museum in New Bedford, Massachusetts has Russell & Purrington's panorama of a Whaling Voyage Round the World, though it is currently (2007) no longer on display. A Mormon Panorama also survives at Brigham Young University's Art Museum.