Venture capital

Venture capital (also known as VC or venture) is a type of private equity capital typically provided to immature, high-potential, growth companies in the interest of generating a return through an eventual realization event such as an initial public offering (IPO) or trade sale of the company. Venture capital investments are generally made as cash in exchange for shares in the invested company. Venture capital typically comes from institutional investors and high net worth individuals and is pooled together by dedicated investment firms.

Who are Venture Capitalists ?

A venture capitalist (also known as a VC) is a person or investment firm that makes venture investments, and these venture capitalists are expected to bring managerial and technical expertise as well as capital to their investments. A venture capital fund refers to a pooled investment vehicle (often an LP or LLC) that primarily invests the financial capital of third-party investors in enterprises that are too risky for the standard capital markets or bank loans.

Who Needs Venture Capital ?

Venture capital is most attractive for new companies with limited operating history that are too small to raise capital in the public markets and are too immature to secure a bank loan or complete a debt offering. In exchange for the high risk that venture capitalists assume by investing in smaller and less mature companies, venture capitalists usually get significant control over company decisions, in addition to a significant portion of the company's ownership (and consequently value).

Origins of modern private equity

Before World War II, venture capital investments (originally known as "development capital") were primarily the domain of wealthy individuals and families. It was not until after World War II that what is considered today to be true private equity investments began to emerge marked by the founding of the first two venture capital firms in 1946: American Research and Development Corporation. (ARDC) and J.H. Whitney & Company.[1]

ARDC was founded by Georges Doriot, the "father of venture capitalism"[2] (former dean of Harvard Business School), with Ralph Flanders and Karl Compton (former president of MIT), to encourage private sector investments in businesses run by soldiers who were returning from World War II. ARDC's significance was primarily that it was the first institutional private equity investment firm that raised capital from sources other than wealthy families although it had several notable investment successes as well.[3] ARDC is credited with the first major venture capital success story when its 1957 investment of $70,000 in Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) would be valued at over $355 million after the company's initial public offering in 1968 (representing a return of over 500 times on its investment and an annualized rate of return of 101%).[4]

- ↑ Introduction to Venture Capital and Private Equity Finance. Retrieved on 2008-07-24.

- ↑ Joseph W Bartlett. What is a Venture Capital?. Retrieved on 2008-07-24.

- ↑ Joel Kurtzman (March 27, 1988). Prospects; Venture Capital. The New York Times. Retrieved on July 24, 2008.

- ↑ Making a VC investment. Retrieved on July 24, 2008.

Former employees of ARDC went on to found several prominent venture capital firms including Greylock Partners (founded in 1965 by Charlie Waite and Bill Elfers) and Morgan, Holland Ventures, the predecessor of Flagship Ventures (founded in 1982 by James Morgan).[5] ARDC continued investing until 1971 with the retirement of Doriot. In 1972, Doriot merged ARDC with Textron after having invested in over 150 companies.

J.H. Whitney & Company was founded by John Hay Whitney and his partner Benno Schmidt. Whitney had been investing since the 1930s, founding Pioneer Pictures in 1933 and acquiring a 15% interest in Technicolor Corporation with his cousin Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney. By far Whitney's most famous investment was in Florida Foods Corporation. The company developed an innovative method for delivering nutrition to American soldiers, which later came to be known as Minute Maid orange juice and was sold to The Coca-Cola Company in 1960. J.H. Whitney & Company continues to make investments in leveraged buyout transactions and raised $750 million for its sixth institutional private equity fund in 2005.

One way to define traditional "venture capital," therefore, is to repeat General Doriot's rules of investing, the thought being that an investment process entailing Doriot's rules is, by definition, a venture-capital process. According to Doriot, investments considered by AR&D involved:

- new technology, new marketing concepts, and new product application possibilities;

- a significant, although not necessarily controlling, participation by the investors in the company's management;

- investment in ventures staffed by people of outstanding competence and integrity (herein the rule often referred to in venture capital as "bet the jockey, not the horse");

- products or processes which have passed through at least the early prototype stage and are adequately protected by patents, copyrights, or trade-secret agreements (the latter rule is often referred to as investing in situations where the information is "proprietary" (proprietary information));

- situations which show promise to mature within a few years to the point of an initial public offering or a sale of the entire company (commonly referred to as the "exit strategy");

- opportunities in which the venture capitalist can make a contribution beyond the capital dollars invested (often referred to as the "value-added strategy").

Venture capital firms and funds

“Venture capital is exceptionally vibrant. The scarcest resource is not capital, but talented venture capital professionals who can guide companies as they grow” - Joel Kurtzman.

Structure of venture capital firms

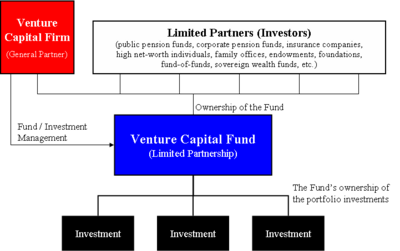

Venture capital firms are typically structured as partnerships, the general partners of which serve as the managers of the firm and will serve as investment advisors to the venture capital funds raised. Venture capital firms may also be structured as limited liability companies, in which case the firm's managers are known as managing members. Investors in venture capital funds are known as limited partners. This constituency comprises both high net worth individuals and institutions with large amounts of available capital, such as state and private pension funds, university financial endowments, foundations, insurance companies, and pooled investment vehicles, called fund of funds or mutual funds.

Roles within venture capital firms

Within the venture capital industry, the general partners and other investment professionals of the venture capital firm are often referred to as "venture capitalists" or "VCs". Typical career backgrounds vary, but broadly speaking venture capitalists come from either an operational or a finance background. Venture capitalists with an operational background tend to be former founders or executives of companies similar to those which the partnership finances or will have served as management consultants. Venture capitalists with finance backgrounds tend to have investment banking or other corporate finance experience.

Although the titles are not entirely uniform from firm to firm, other positions at venture capital firms include:

- Venture partners - Venture partners are expected to source potential investment opportunities ("bring in deals") and typically are compensated only for those deals with which they are involved.

- Entrepreneur-in-residence (EIR) - EIRs are experts in a particular domain and perform due diligence on potential deals. EIRs are engaged by venture capital firms temporarily (six to 18 months) and are expected to develop and pitch startup ideas to their host firm (although neither party is bound to work with each other). Some EIR's move on to executive positions within a portfolio company.

- Principal - This is a mid-level investment professional position, and often considered a "partner-track" position. Principals will have been promoted from a senior associate position or who have commensurate experience in another field such as investment banking or management consulting.

- Associate - This is typically the most junior apprentice position within a venture capital firm. After a few successful years, an associate may move up to the "senior associate" position and potentially principal and beyond. Associates will often have worked for 1-2 years in another field such as investment banking or management consulting.

Structure of the funds

Most venture capital funds have a fixed life of 10 years, with the possibility of a few years of extensions to allow for private companies still seeking liquidity. The investing cycle for most funds is generally three to five years, after which the focus is managing and making follow-on investments in an existing portfolio. This model was pioneered by successful funds in Silicon Valley through the 1980s to invest in technological trends broadly but only during their period of ascendance, and to cut exposure to management and marketing risks of any individual firm or its product.

In such a fund, the investors have a fixed commitment to the fund that is initially unfunded and subsequently "called down" by the venture capital fund over time as the fund makes its investments. There are substantial penalties for a Limited Partner (or investor) that fails to participate in a capital call.

Compensation

Venture capitalists are compensated through a combination of management fees and carried interest (often referred to as a "two and 20" arrangement:

- Management fees – an annual payment made by the investors in the fund to the fund's manager to pay for the private equity firm's investment operations.[16] In a typical venture capital fund, the general partners receive an annual management fee equal to up to 2% of the committed capital.

- Carried interest - a share of the profits of the fund (typically up to 20%), paid to the private equity fund’s management company as a performance incentive. The remaining 80% of the profits are paid to the fund's investors[16] Strong Limited Partner interest in top-tier venture firms has led to a general trend toward terms more favorable to the venture partnership, and certain groups are able to command carried interest of 25-30% on their funds.

Because a fund may run out of capital prior to the end of its life, larger venture capital firms usually have several overlapping funds at the same time; this lets the larger firm keep specialists in all stages of the development of firms almost constantly engaged. Smaller firms tend to thrive or fail with their initial industry contacts; by the time the fund cashes out, an entirely-new generation of technologies and people is ascending, whom the general partners may not know well, and so it is prudent to reassess and shift industries or personnel rather than attempt to simply invest more in the industry or people the partners already know.

Venture capital funding

Venture capital is not generally suitable for all entrepreneurs. Venture capitalists are typically very selective in deciding what to invest in; as a rule of thumb, a fund may invest in as few as one in four hundred opportunities presented to it. Funds are most interested in ventures with exceptionally high growth potential, as only such opportunities are likely capable of providing the financial returns and successful exit event within the required timeframe (typically 3-7 years) that venture capitalists expect.

Because investments are illiquid and require 3-7 years to harvest, venture capitalists are expected to carry out detailed due diligence prior to investment. Venture capitalists also are expected to nurture the companies in which they invest, in order to increase the likelihood of reaching a IPO stage when valuations are favourable. Venture capitalists typically assist at four stages in the company's development:[17]

- Idea generation;

- Start-up;

- Ramp up; and

- Exit

This need for high returns makes venture funding an expensive capital source for companies, and most suitable for businesses having large up-front capital requirements which cannot be financed by cheaper alternatives such as debt. That is most commonly the case for intangible assets such as software, and other intellectual property, whose value is unproven. In turn this explains why venture capital is most prevalent in the fast-growing technology and life sciences or biotechnology fields.

If a company does have the qualities venture capitalists seek including a solid business plan, a good management team, investment and passion from the founders, a good potential to exit the investment before the end of their funding cycle, and target minimum returns in excess of 40% per year, it will find it easier to raise venture capital.

Alternatives to venture capital

Because of the strict requirements venture capitalists have for potential investments, many entrepreneurs seek initial funding from angel investors, who may be more willing to invest in highly speculative opportunities, or may have a prior relationship with the entrepreneur.

Furthermore, many venture capital firms will only seriously evaluate an investment in a start-up otherwise unknown to them if the company can prove at least some of its claims about the technology and/or market potential for its product or services. To achieve this, or even just to avoid the dilutive effects of receiving funding before such claims are proven, many start-ups seek to self-finance until they reach a point where they can credibly approach outside capital providers such as venture capitalists or angel investors. This practice is called "bootstrapping".

There has been some debate since the dot com boom that a "funding gap" has developed between the friends and family investments typically in the $0 to $250,000 range and the amounts that most Venture Capital Funds prefer to invest between $1 to $2MM. This funding gap may be accentuated by the fact that some successful Venture Capital funds have been drawn to raise ever-larger funds, requiring them to search for correspondingly larger investment opportunities. This 'gap' is often filled by angel investors as well as equity investment companies who specialize in investments in startups from the range of $250,000 to $1MM. The National Venture Capital association estimates that the latter now invest more than $30 billion a year in the USA in contrast to the $20 billion a year invested by organized Venture Capital funds.[citation needed]

In industries where assets can be securitized effectively because they reliably generate future revenue streams or have a good potential for resale in case of foreclosure, businesses may more cheaply be able to raise debt to finance their growth. Good examples would include asset-intensive extractive industries such as mining, or manufacturing industries. Offshore funding is provided via specialist venture capital trusts which seek to utilise securitization in structuring hybrid multi market transactions via an SPV (special purpose vehicle): a corporate entity that is designed solely for the purpose of the financing.

In addition to traditional venture capital and angel networks, groups have emerged which allow groups of small investors or entrepreneurs themselves to compete in a privatized business plan competition where the group itself serves as the investor through a democratic process.

Venture Capital Firms

- Kleiner, Perkins, Caufield & Byers

- Mayfield Fund

- New Enterprise Associates

- Oak Investment Partners

- Sequoia Capital

- Sigma Partners

- Fidelity Ventures

- Enterprise Partners

- Benchmark Capital

List of Institutional investors

- Banks

- Building societies

- Collective investment schemes

- Credit Unions

- Insurance companies

- Investment banks

- Pension funds

- Prime Brokers

- Trusts