Bariatric surgery

This page was started in the framework of an Eduzendium course and needs to be assessed for quality. If this is done, this {{EZnotice}} can be removed.

Obesity is becoming a global pandemic whose manifestations are causing drastic consequences to our health and economy. Currenty Bariatric surgery is the most effective treatment for obesity. In this article we shall discuss the specific bariatric operations and report how surgury effects hormonal modulation of both the gut-brain and adipose-brain axes. Our furthur understading of how bariatric surgery works will yield novel pharmaceuticals in the treamtent for metabolic disorders.

Introduction

Surgery as a treatment for obesity

For many obese patients, diets and lifestlye changes do not work in long term. Bariatric surgery has proved to be the only effective method in the long term treatment of obesity.

How surgery works

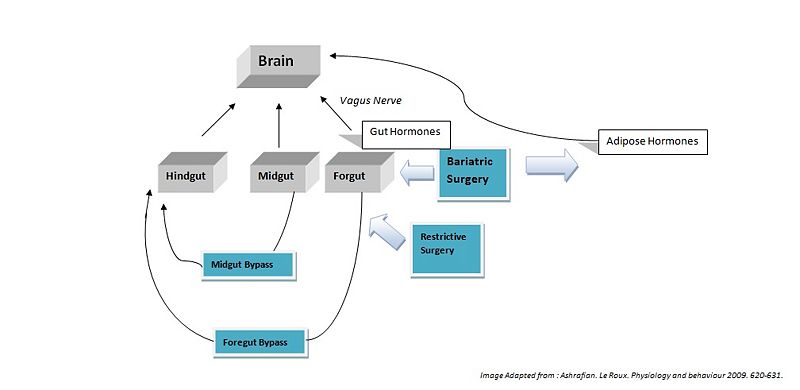

Bariatric surgery works by altering the anatomy of the gastrointestinal tract, thus: limiting the volume of food the stomach can hold, interfering with the absorption of calories, and by interfering with orexigenic and anorexigenic signalling between the gut, adipose tissues and the brain.

Bariatric Surgical Procedures

Restrictive Surgery

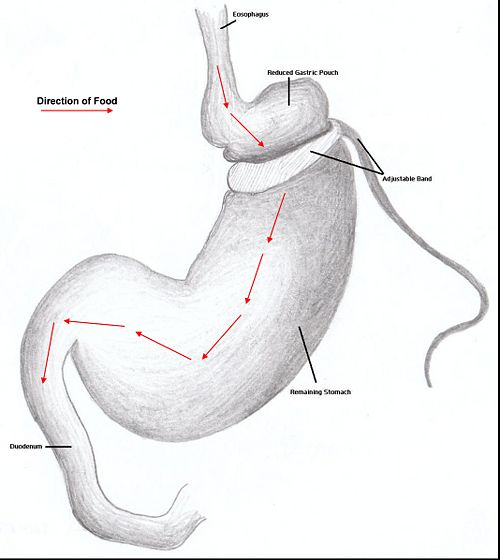

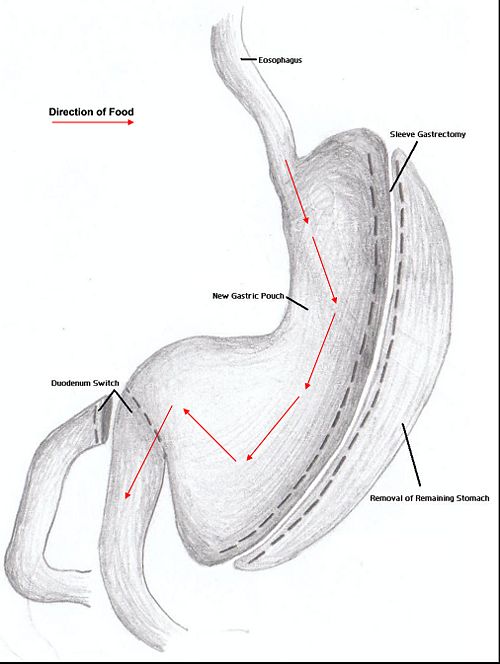

Restrictive surgery reduces the size of the stomach causing decreased hunger and an increased satiety following ingestion of smaller amounts of food. Surgical procedures include gastric banding, where an adjustable band is clipped just below the cardia of the stomach creating a small gastric pouch above(kerrigan, le roux). Other forms of restrictive surgery includes gastroplasty and sleeve gasrectomy.

Malabsorptive Surgery

Jejuno-ileal bypass, duodenojejunal bypass and biolopancreatic bypass (with or without duodenal switch)

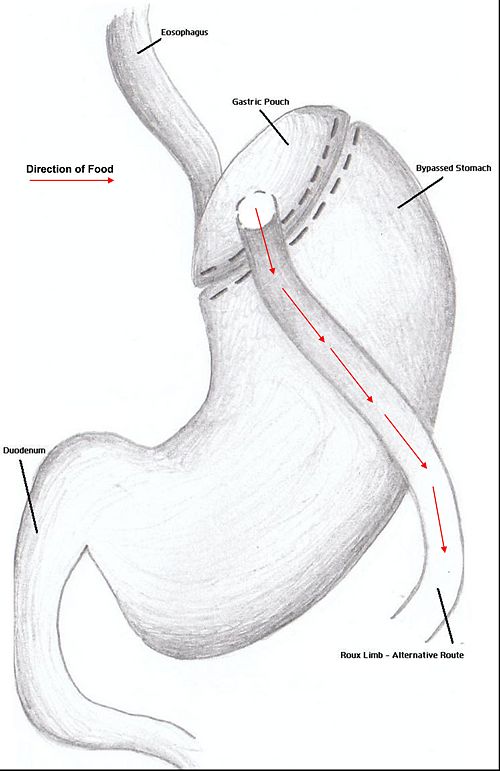

Combination Surgery

Combination surgery combines the benefits of both restrictive and restrictive surgery. The most common bariatric procedure in the US is the Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGP).

Duodenal switch

Complications and Side effects

Surgical Effects Regarding Gut Hormones

Hindgut Hormones

Peptide tyrosine tyrosine (PYY) is a peptide belonging to the neuropeptide Y (NPY) family [1]. PYY is normally released in proportion to calorie intake and has recently been described as an important feedback molecule in the Gut-Brain axis. Following bypass and restrictive surgery, basal and postprandial PYY levels have been shown to increase [2]. In addition basal PYY levels have been shown to increase following illial resection, and patients have been reported to have lost weight (broberger,2005). As well as being a satiety signal PPY has also been suggested to increase energy expenditure [3].

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), acts similarly to PYY, acting in the hypothalamus as an anorexigenic signal. The literature shows the majority of patients following foregut bypass surgery show a marked increase in basal and postprandial GLP-1. Midgut bypass also shows an increase in GLP-1 however studies on restrictive surgery have shown either no change or a decrease in GLP-1 basal levels. Of specific interest GLP-1 has been shown to improve postpriandal glycaemic control, being a potent incretin mimetic. A GLP-1 agonist, exenatide has not yet been accepted for use as an anti-obesity drug; however it is already being used in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (Ashrafian, 2009).

Midgut Hormones

Neurotensin (NT), is a well know anoregigenic signal where its expression has been shown to be downregulated in ob/ob leptin defficient mice. Following bypass surgerys (5 of 6 reported) an increase in NT levels has been demonstrated which could contribute to the anorexigenic effects of the bypass operations (Ashrafian, 2009).

Foregut Hormones

Ghrelin is an orexigenic hormone and is released from the forgut. It is released into the blood to promote eating, and levels begin to fall after meals when satiety is reached. Ghrelin is also believed to play a role in regulating body weight over a long period of time. As a result, ghrelin levels increase in order to compensate for the starvation induced by reduced calorie intake observed in diets. It would be assumed that bariatric surgery reduces hunger by lowering the amount of ghrenlin released however the results from the literature remain controversial. Of a total of 42 studies following forgut bypass surgerys, only 50% reported a decrease in ghrenlin release. A large number of these studies reported ghrelin levels immediately after surgery, whereas studies of long term ghrelin change following surgery show no significant trend. Results for restrictive surgeries shows only a 18% decrease in ghrenlin levels. These results indicated bariatric surgeries may not directly modulate Grenlin release.

Cholecystokinin (CKK) was the first anoregixigenic gut peptide to be implicated in the control of appetite (murphy). One would speculate that CCK would rise following bariatric surgery however the results from the literature have been disappointing and suggest no role in the mediation of CCK following bariatric surgery (ashrafan).

Gastrin

Other Hormones

Surgical Treatment as Opposed to Diet

It should be noted that this area of how bariatric surgery works is still quite controversial. Nevertheless, clinical observations demonstrate the effectiveness of surgery as opposed to diet. An attractive theory is as follows; when an individual consumes excessive amounts of calories satiety signals become abundant and their corresponding receptors become either desensitized or down regulated. Now when this obese individual attempts to lose weight by diet, satiety signals are ineffective. Thus the individual remains hungry. In addition in obese individuals following diets, body metabolism is so low that it makes dieting near to imposable. Bariatric surgery is proposed to work by increasing energy metabolism, reducing orexigenic signals, increasing anorexigenic signals and interfering with calorie absorption. The precise functioning of these systems shall remain at the heart of controversy. Physiological reasoning is beyond the scope of this article however must also be considered.

Future Possibilites and Conclusion

There is no doubt that further understanding of the physiology of how each specific operation effects hormonal modulation will lead to new pharmaceutical treatments in the treatment of obesity and appetite disorders.

Conclusion

References

Broberger, C. "Brain Regulation of food intake and appetite: molecules and networks" Journal of internal Medicine (2005); 258: 301-327.[2]

DeMaria "Bariatric Surgery for Morbid Obesity". The new England Journal of Medicine (2007); 356; 2176-83 [3]

Murphy, K.G. "Gut Hormones in the control of appetite" Exp Physiol 89. pp 507-616. [4]