Battle of Ap Bac

A relatively small engagement that had major media, political, and policy implications, the Battle of Ap Bac took place between Viet Cong (VC) and Army of the Republic of Viet Nam (ARVN) forces on January 2, 1963. It took place in an area of the Mekong Delta that had been dominated by VC guerillas.

Background

In December, U.S. Army signals intelligence aircraft, using direction finding techniques, located a Viet Cong radio transmitter in Tan Thoi hamlet, 14 miles northwest of My Tho, the headquarters of the ARVN 7th Division, at the time commanded by colonel Huynh Van Cao. Cao's American advisor was Lieutanant Colonel John Paul Vann.[1] Communist guerilla forces needed to be of fair size before they had a radio transmitter, and that it stayed in one place suggested some level of strength.

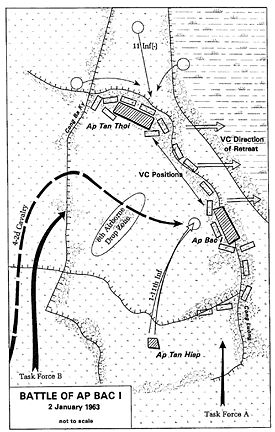

Nevertheless, Vietnamese Army intelligence had reported a reinforced Viet Cong company in Tan Thoi, 1,500 meters northwest of Ap Bac. Following Joint General Staff orders of December 28, the ARVN 7th Division, planned an operation to trap the Viet Cong, by landing the 11th ARVN Infantry Regiment to the north by helicopter while a provisional regiment of two battalion-size task forces of Civil Guards (later named Regional Forces) moved in from the south. [2] Civil Guards reported through the province chiefs, and were not in the military chain of command; coordination coulld be hit or miss.

A unit of M113 (armored personnel carrier|M113 armored personnel carriers]], the 4th Mechanized Rifle Squadron, 2d Armored Cavalry, commanded by Captain Ly Tong Ba, was attached to the provisional regiment and was to attack from the southwest. Two American advisors were with the M113 unit.

Three Vietnamese Ranger and infantry companies were in reserve, with artillery and air support on call.

Concept of operations

Cao had been promoted to brigadier general and given command of the new IV Corps tactical zone. He promoted his chief of staff, Bui Danh Dam, to the command of the division. Dam was hesitant; he considered himself a good administrator but not fitted for combat command. Cao, regarding Dam as a politically reliable Catholic, like President Ngo Dinh Diem, urged him to accept. Dam was regarded as honest and cooperative by his American advisors. [3]

Soldiers in armored fighting vehicles, as well as helicopter-borne air assault, units, are expected to use the classic cavalry attack tactics, which are based on speed and shock. They had done so in an action in the Plain of Reeds in July 1962. [4]

Intelligence estimates of enemy strength were wrong. The Viet Cong were actually actually actually the 261st Main Force Battalion, supported with additional machine guns, mortars, and several local guerrilla units.

The attack was no surprise, and the VC were in defensive positions along the Cong Luong Canal, from Ap Tan Thoi to Ap Bac. The defensive positions were concealed but had excellent fields of fire. [5] While the Viet Cong did not know exactly where the attack would strike, they were warned by the arrival of 71 truckloads of ammunition and supplies in My Tho. While the Communists had felt in control of the area, the previous shock of helicopters, artillery and air support were so strong that tactics that worked against the French would not prevail. As the People's Army of North Vietnam were to do at the Battle of the Ia Drang, the forces needed to find a way to fight American resources, even if the direct fight would be with ARVN troops. [6]

Early contact

As the mobile forces moved toward the area, the Civil Guard had made contact, but their commander, Dinh Tuong province chief MAJ Lam Quang Tho, had not informed Dam of the contact until it was almost over, and then, not sending in his own reserves, asked Dam to airland the division reserve companies and outflank the VC fighting his men. He did not realize that the proposed landing zone, at Bac, was the prepared fighting area for the rest of the VC.

Vann, in a light aircraft, thought Bac was a logical assembly area, but could see nothing specific from the air. He gave the leader of the U.S. helicopter unit, carrying the ARVN reserve, an approach that he thought would keep the helicopters out of range of any VC antiaircrft. That helicopter unit, however, was not under his direct authority, and he was distrusted by aviators that thought he tried to give them orders in their area of expertise.

The VC knew the helicopter radio frequency and prepared fr them, opening fire as they were on final approach. The ARVN lieutenant commanding the landing force froze, but an American sergeant with him was able to rally the soldiers; after several helicopters were shot down and Sergeant First Class Arnold Bowers was able to rescue survivors, the lieutenant reasserted himself. When Bowers asked for the single radio, to call in air strikes against the VC. Another ARVN lieutenant, a forward observer with the only other radio, also was ineffective.

Vann, seeing the situation from the air, called for the M113s to move into the area, but the American advisors told Vann that Ba would not move, saying "I don't take orders fro Americans". Ba did have a challenging situation, in that the far side of the canal did not offer a good crossing point near his position. Capt. James Scanlon, one of the advisors, was surprised, as Ba had been aggressive in the past. Ba's perspective had changed, however, due to South Vietnamese politics. President Diem, as a safeguard against their use in a coup, had taken the M113 units out from Dam's control, and put them under the province chief, Tho. Ba would not move without approval from Tho.

References

- ↑ Sheehan, Neil. (1988), A bright shining lie: John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam, New Random House, pp. 203-204

- ↑ {{ | first = Donn A. | last = Starry | title = Vietnam Studies: Mounted Combat in Vietnam | contribution = Chapter II: Armor in the South Vietnamese Army | publisher = Office of the Chief of Military History, United States Army | url = http://www.history.army.mil/books/Vietnam/mounted/chapter2.htm}}, pp. 25-26

- ↑ Sheehan, p. 204

- ↑ Sheehan, pp. 81-87

- ↑ Starry, p. 26

- ↑ Vann, pp. 206-207