User:Milton Beychok/Sandbox

Asphalt is a sticky, black and highly viscous liquid or semi-solid that is present in most petroleum crude oils and in some natural deposits. Crude oil is a complex mixture of a great many different hydrocarbons. Petroleum asphalt is defined as that part of crude oil which is separated from the higher-boiling hydrocarbons in crude oil by precipitation upon the addition of lower-boiling hydrocarbon solvents such as propane, pentane, hexane or heptane. The precipitated material consists of asphaltenes which are high molecular weight (800 - 2500 g/mole) compounds that exist in the form of flat sheets of polyaromatic condensed rings with short aliphatic chains.

Over the years, petroleum asphalt has been referred to as bitumen, asphaltum or pitch. The terminology varies from country to country and from individual to individual. Asphalt is often confused with coal tar (or coal pitch) derived from the pyrolosis of coal and which has a different chemical structure than asphalt.

When petroleum asphalt is combined with construction aggregate (sand, gravel, crushed stone, etc.) for use in road construction, it has often been referred to as asphaltic concrete, asphaltic cement, bituminous concrete, blacktop or road tar (see Asphalt (paving).

The natural deposits of asphalt (often referred to as tar) include asphaltic lakes such as Bermudez Lake in Venezuela, and Pitch Lake in Trinidad. Other natural deposits include tar sands (sometimes called oil sands) and the two largest deposits of tar sands are such as in Alberta, Canada and the Orinoco Oil Belt area of Venezuela.

Production process

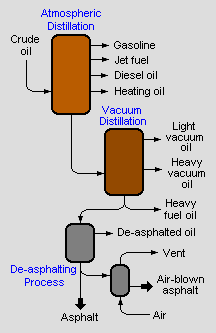

Asphalt can be separated from the other components in crude oil (such as naphtha, gasoline and diesel) by the process of fractional distillation, usually under vacuum conditions. A better separation can be achieved by further processing of the heavier fractions of the crude oil in a de-asphalting unit, which uses either propane or butane in a supercritical phase to dissolve the lighter molecules which are then separated. Further processing is possible by "blowing" the product: namely reacting it with oxygen. This makes the product harder and more viscous.

Asphalt is typically stored and transported at temperatures around 300 degrees Fahrenheit (150° C). Sometimes diesel oil or kerosene are mixed in before shipping to retain liquidity; upon delivery, these lighter materials are separated out of the mixture. This mixture is often called bitumen feedstock, or BFS. Some dump trucks route the hot engine exhaust through pipes in the dump body to keep the material warm. The backs of tippers carrying asphalt, as well as some handling equipment, are also commonly sprayed with a releasing agent before filling to aid release. Diesel oil is sometimes used as a release agent, although it can mix with and thereby reduce the quality of the asphalt.

Historical uses

In the ancient Middle East, natural asphalt deposits were used for mortar between bricks and stones, ship caulking, and waterproofing. The Persian word for asphalt is mumiya, which may be related to the English word mummy. Asphalt was also used by ancient Egyptians to embalm mummies.

In the ancient Far East, natural asphalt was slowly boiled to get rid of the higher fractions, leaving a material of higher molecular weight which is thermoplastic and when layered on objects, became quite hard upon cooling. This was used to cover scabbards and other objects that needed water-proofing. Statuettes of household deities were also cast with this type of material in Japan, and probably also in China.

In North America archaeological recovery has indicated that asphaltum was sometimes used to apply stone projectile points to a wooden haft.[1]

During the early-twentieth century when coal was being gasified to produce town gas, the by-product tar was a readily available product. The extensive use of that tar (as a binder for constuction aggregates) in the paving of roads and airports led to the words macadam and tarmac, which are now sometimes used to refer to road making materials. However, since natural gas replaced town gas, petroleum asphalt has completely overtaken the use of coal-derived tar in road and other paving applications.

Current Uses

Road construction

The largest use of petroleum asphalt is for making asphalt concrete for road constuction and accounts for approximately 80% of the asphalt consumed in the United States. The asphalt is used as the binder or glue that holds together the aggregate of sand, gravel, crushed stone, slag or other material.

There are various mixtures of asphalt with other materials that are used in road construction and other paving applications:

- Rolled asphaltic concrete that contains about 95% aggregate and 5% petroleum asphalt binder.

- Mastic asphalt that contains about 90–93% aggregate and 7–10% petroleum asphalt binder.

- Asphalt emulsions that contains about 70% petroleum asphalt and 30% water plus a small amount of chemical additives.

- Cutback asphalt that contains petroleum solvents (referred to as cutbacks).

Roofing shingles

Roofing shingles account for most of the remaining asphalt consumption in the United States.

Other uses

- Asphaltic concrete is widely used for paving vehicle parking lots and aircraft landing and take-off runways in airports around the world

- Canal and reservoir linings as well as dam facings

- Floor tiles

- Battery casings

- Waterproofing of fabrics and various other materials

- Treatment of fence posts and other wooden objects

- Cattle sprays

References

Yet to do

- Brief section on processing of tar sands as in Canada

- Re-write history section. Use Speight's table?

- Re-write production process section

- Add more references ... and more books for Bibliography subpage

- Expand section on roofing shingles

Possible References and Books

- Joann A. Wess, Larry D. Olsen and Marie H. Sweeny (2004). Asphalt (bitumen). World Health Organization. ISBN 92-4-153059-6.

- Oliver Mullins and Eric Sheu (1999). Structure & Dynamics of Asphaltenes, 1st Edition. Springer. ISBN 0-306-45930-2.

- Edwin J. Booth (1962). Asphalt: Science and Technology, 1st Edition. Gordon and Breach Science Publishers. ISBN 0-677-00040-5.

- David S.J. Jones and Peter P.Pujado (Editors) (2006). Handbook of Petroleum Processing, First Edition. Springer. ISBN 1-4020-2819-9.

- J.G. Speight and Baki Ozum (2002). Petroleum Refining Processes. Marcel Dekker. ISBN 0-8247-0599-8.

- OSHA Technical Manual, Asphalt Production From website of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA)

- Experimental Investigation of Asphaltene Precipitation From website of the Research Institute of Petroleum Industry in Tehran, Iran

- History item: Origin of “macadam”: 1824, named for inventor, Scot. civil engineer John L. McAdam (1756-1836), who developed a method of leveling roads and paving them with gravel and outlined the process in his pamphlet "Remarks on the Present System of Road-Making" (1822). Originally, road material consisting of a solid mass of stones of nearly uniform size laid down in layers; he did not approve of the use of binding materials or rollers. The idea of mixing tar with the gravel began 1880s. Verb macadamize is first recorded 1826. "macadam", from Online Etymology Dictionary by Douglas Harper, Historian

- History of Asphalt From website of the National Asphalt Pavement Association