U.S. slavery era

The history of slavery in the United States began soon after Europeans first settled in what became the United States. All slaves were freed by 1865 during the American Civil War, most by Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation but finally and completely by the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

From about the 1640s until 1865, people of African descent were legally enslaved within the boundaries of the present United States by whites, American Indians and free blacks. Holding Indians as slaves was practiced by whites in the 17th century and as late as 1867 in the case of the Tlingit tribe in Alaska which owned Indian slaves. The economy of the country was enhanced by the labor afforded by slavery.

About 300,000 slaves were imported into the U.S. The great majority of the 12 million slaves brought across from, Africa went to sugar colonies in the Caribbean and Brazil, where life expectancy was short. Life expectancy was muich higher in the U.S. (because of better food and less severe discipline), so the numbers grew rapidly, reaching 4 million by the 1860 Census. In the Caribbean the slave population did not reproduce itself and had to be replenished every few years. From the later eighteenth century, and possibly before that even, and until the Civil War, the rate of natural growth of North American slaves was much greater than for the population of any nation in Europe, and was nearly twice as rapid as that of England. [1]

Colonial America

The first record of Africans in colonial America is of a Dutch ship which brought twenty blacks recorded and sold them to the English colony of Jamestown, Virginia, in 1619 as indentured servants. Indentured servants had to work for a master for a fixed number of years and then were free, and these blacks were freed on schedule. Anthony Johnson eventually became a landowner on the Eastern Shore and a slave owner himself.

The transformation from indentured servitude to racial slavery happened gradually. There are no laws regarding slavery early in Virginia's history. However, by 1640, the Virginia courts had sentenced at least one black servant to slavery. In 1654, a court in Northampton County ruled against one John Casor, declaring him the chattel (property) of Anthony Johnson, also a black man, for life.

The Virginia "Slave codes" of 1705 made clear the status of slaves. During the British colonial period, every colony had slavery. Those in the north were primarily house servants. Early on, slaves in the South worked on farms and plantations growing indigo, rice, and tobacco; cotton became a major crop after 1790s. Slaves were expensive and were used by rich farmers and plantation owners with commercial export-oriented operations on the best lands. The backwoods subsistence farmers seldom owned slaves.

Native Americans

During the 17th century, enslavement of Native Americans was common. Many of these Native slaves were exported to other colonies, especially the "sugar islands" of the Caribbean. Historian Alan Gallay estimates the number of Natives in the South sold in the British slave trade from 1670-1715 at between 24,000 and 51,000. [2]

After 1800, the Cherokees and other Indian tribes started buying and using black slaves, a practice they continued after being relocated to Indian Territory in the 1830s. In the American Civil War they sided with the Confederacy; their slaves were freed by the Emancipation Proclamation.

Decline of slave trade

Some of the British colonies attempted to abolish the international slave trade, fearing that new Africans would be disruptive. Virginia's Acts to that effect were vetoed by the British Privy Council; Rhode Island forbade the importation of slaves completely in 1774. All of the states except Georgia had banned or limited it by 1786; Georgia did so in 1798 - although some of these laws were later repealed.[3]

1776 to 1850

Treatment of slaves

Treatment of slaves was very harsh and inhumane. Whether laboring or walking about in public, people living as slaves were regulated by legally authorized violence. On large plantations, slave overseers were authorized to whip and brutalize noncompliant slaves. Slave codes authorized, or even required the use of violence, and were denounced by abolitionists for their brutality. Both slaves and free Negroes were regulated and had their movements monitored by slave patrols. In addition to such physical abuses, slaves were at constant risk of losing members of their families if their owners decided to trade them for profit or to pay debts. Some slaves retaliated by murdering owners and overseers, burning barns, killing horses, or staging work slowdowns. [4]

Slaves were a very expensive investment and were fed, clothed, housed and provided medical care. It was common to pay bonuses at Christmas season and allowed slaves to keep earnings and gambling profits. (One slave, Denmark Vesey, won the lottery and bought his own freedom.) In many households, treatment of slaves varied with the slave's skin color. Darker-skinned slaves worked in the fields, while lighter-skinned house servants had better clothing, food and housing.[5]

Beginning in the 1750s. There was widespread sentiment during the American Revolution that slavery was a social evil (for the country as a whole and for the whites) and should eventually be abolished. All the Northern states passed emancipation acts between 1780 and 1804; most of these arranged for gradual emancipation and a special status for freedmen, so there were still a dozen "permanent apprentices" in New Jersey in 1860. [6]

The Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 declares all men "born free and equal"; the slave Quork Walker sued for his freedom on this basis and won his freedom, thus abolishing slavery in Massachusetts.

Throughout the first half of the 19th century, a movement to end slavery grew in strength throughout the United States. This reform took place amidst strong support of slavery among white Southerners, who began to refer to it as the "peculiar institution" in a defensive attempt to differentiate it from other examples of forced labor.

The large, well-funded American Colonization Society had an active program of shipping ex-slaves and free blacks who volunteered back to Africa to the American colony of Liberia.

After 1830, a religious movement led by William Lloyd Garrison declared slavery to be a personal sin and demanded the owners repent immediately and start the process of emancipation. The movement was highly controversial and was a factor in causing the American Civil War.

A very few abolitionists, such as John Brown, used armed force to foment uprisings among the slaves.

Influential leaders of the abolition movement (1810-60) included:

- William Lloyd Garrison - Published The Liberator newspaper

- Harriet Beecher Stowe - Author of Uncle Tom's Cabin

- Frederick Douglass - Nation's most powerful anti-slavery speaker, a former slave. Most famous for his book, "Narrative in the Life of Frederick Douglass.

- Harriet Tubman - Helped 350 slaves escape from the South, became known as a "conductor" on the Underground Railroad.

Slave uprisings that used armed force (1700 - 1859) include:

- New York Revolt of 1712

- The Stono Rebellion (1739) in South Carolina

- New York Slave Insurrection of 1741

- Gabriel's Rebellion (1800) in Virginia

- Louisiana Territory Slave Rebellion, led by Charles Deslandes (1811)

- George Boxley Rebellion (1815) in Virginia

- Fort Blount Revolt (1816) in Florida

- Denmark Vesey Uprising in Virginia (1822)

- Nat Turner's Rebellion (1831) in Virginia

- The Amistad Seizure (1839) on a Spanish ship

Rising tensions

The economic value of plantation slavery was reinforced in 1793 with the invention of the cotton gin by Eli Whitney,a device designed to separate cotton fibers from seedpods and the sometimes sticky seeds. The invention revolutionized the cotton-growing industry by increasing the quantity of cotton that could be processed in a day by fiftyfold. The result was explosive growth in the cotton industry and a proportionate increase in the demand for slave labor in the South.

At the same time, the northern states banned slavery, though as Alexis De Toqueville pointed out in Democracy in America (1835), this was not always done with the best of motives. As the northern states abolished slavery, it did not always mean that the slaves were freed. In many cases, it simply encouraged slave owners to move their slaves to states which still allowed slavery. This resulted in a population movement of black Americans to the South. The southern states did not have this option of removing their black population since slaves were already a much higher proportion of the total population, and the international slave trade had been abolished. This led to a hardening of opinions in favor of slavery in the southern states out of fear of what the slaves would do if they were freed.

Just as demand for slaves was increasing, supply was restricted. The United States Constitution, adopted in 1787, allowed to ban the importation of slaves after 1808. In 1808, Congress acted to ban further imports. Any new slaves would have to be descendants of ones that were currently in the U.S. However, the internal U.S. slave trade, and the involvement in the international slave trade or the outfitting of ships for that trade by U.S. citizens, were not banned. Though there were certainly violations of this law, slavery in America became more or less self-sustaining; the overland 'slave trade' from Virginia, and the Carolinas to Georgia, Alabama, and Texas continued for another half-century.

Because of the three-fifths compromise in the United States Constitution, slaveholders exerted their power through the Federal Government and the resulting Federal Fugitive slave laws. Refugees from slavery fled the South across the Ohio River to the North via the Underground Railroad, and their physical presence in Cincinnati, Oberlin, and other Northern towns agitated Northerners. After 1854, Republicans fumed that Slave Power, especially the pro-slavery Democratic Party, controlled two or three branches of the Federal government.

Because the Midwestern states decided in the 1820s not to allow slavery and because most Northeastern states became free states through local emancipation, a Northern bloc of free states solidified into one contiguous geographic area. The dividing line was the Ohio River and the Mason-Dixon line (between slave-state Maryland and free-state Pennsylvania).

North and South grew further apart in 1845 with the formation of the Southern Baptist Convention on the premise that the Bible sanctions slavery and that it was acceptable for Christians to own slaves (the Southern Baptist Convention has since renounced this interpretation). This split was triggered by the opposition of northern Baptists to slavery, and in particular by the 1844 statement of the Home Mission Society declaring that a person could not be a missionary and still keep slaves as property. The Methodist and Presbyterian churches likewise divided north and south, so that by the late 1850s only the Democratic Party was a national institution, and it split in the 1860 election.

| Census Year |

# Slaves | # Free blacks |

Total black |

% free blacks |

Total US population |

% black of total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 697,681 | 59,527 | 757,208 | 7.9% | 3,929,214 | 19% |

| 1800 | 893,602 | 108,435 | 1,002,037 | 10.8% | 5,308,483 | 19% |

| 1810 | 1,191,362 | 186,446 | 1,377,808 | 13.5% | 7,239,881 | 19% |

| 1820 | 1,538,022 | 233,634 | 1,771,656 | 13.2% | 9,638,453 | 18% |

| 1830 | 2,009,043 | 319,599 | 2,328,642 | 13.7% | 12,860,702 | 18% |

| 1840 | 2,487,355 | 386,293 | 2,873,648 | 13.4% | 17,063,353 | 17% |

| 1850 | 3,204,313 | 434,495 | 3,638,808 | 11.9% | 23,191,876 | 16% |

| 1860 | 3,953,760 | 488,070 | 4,441,830 | 11.0% | 31,443,321 | 14% |

| 1870 | 0 | 4,880,009 | 4,880,009 | 100% | 38,558,371 | 13% |

| Source: http://www.census.gov/population/documentation/twps0056/tab01.xls | ||||||

Nat Turner, anti-literacy laws

In 1831, a bloody slave rebellion took place in Southampton County, Virginia. A slave named Nat Turner who was able to read and write and had "visions" led what became known as the Southampton Insurrection. On a murderous rampage without an apparent goal, Turner and his followers killed men, women and children, but were eventually subdued by the militia.

Nat Turner and many of his followers were hanged. They had accomplished little except to harm the relationship between the races and generate new fears among whites, an effect which spread far beyond the area of his violent acts. All across the South, new laws were enacted in the aftermath of the 1831 Turner Rebellion. Typical was the Virginia law against educating slaves, free blacks and mulattos. These laws were often defied by individuals, among whom is noted future Confederate General Stonewall Jackson, but they did so at risk to themselves.

1850s to the Civil War

Bleeding Kansas

After the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act,1854, the border wars broke out in Kansas Territory, where the question of whether it would be admitted to the Union as a slave state or a free state was left to the inhabitants. The radical abolitionist John Brown was active in the mayhem and killing in "Bleeding Kansas." At the same time, fears that the Slave Power was seizing full control of the national government swept anti-slavery Republicans into office.

Dred Scott

The Supreme Court tried to resolve the issue, but its 1857 Dred Scott decision only inflamed tempers. The deciding opinion claimed that slavery's presence in the Midwest was lawful (when owners crossed into free states)—further proof for Republicans like Abraham Lincoln that the Slave Power had seized control of the Supreme Court.

1860 presidential election

The divisions became fully exposed with the 1860 presidential election. The electorate split four ways. One party (the Southern Democrats) endorsed slavery. One (the Republicans) denounced it. One (the Northern Democrats) said democracy required the people themselves to decide on slavery locally. The fourth, the Constitutional Union Party said the survival of the Union was at stake and everything else should be compromised.

Lincoln, the Republican, won with a plurality of popular votes and a majority of electoral votes. Lincoln however, did not appear on the ballots of ten southern states: thus his election necessarily split the nation along sectional lines. Many slave owners in the South feared that the real intent of the Republicans was the abolition of slavery in states where it already existed, and that the sudden emancipation of 4 million slaves would be problematic for the slave owners and for the economy that drew its greatest profits from the labor of people who were not paid.

They also argued that banning slavery in new states would upset what they saw as a delicate balance of free states and slave states. Northern leaders like Lincoln had viewed the slavery interests as the "Slave Power" comprising a threat to republicanism and freedom in America, and promised to stop its geographical extension. Everyone believed slavery had to expand or fie, so the republicans were promising to slowly kill slavery. Southerns saw this as a basic violation of their rights and led seven states to secede from the Union and thus began the American Civil War. (Four more slave state seceded when Lincolon called on them for troops to invade the Confederacy; the slave states of Missouri, Kentucky, West Virginia, Maryland and Delaware stayed in the Union.)

War and emancipation

The consequent American Civil War, beginning in 1861, led to the end of chattel slavery in America. Not long after the war broke out, through a legal maneuver credited to Union General Benjamin F. Butler, a lawyer by profession, slaves who came into Union "possession" were considered "contraband of war" and therefore, he ruled that they were not subject to return to Confederate owners as they had been before the War. Soon word spread, and many slaves sought refuge in Union territory, desiring to be declared "contraband." Many of the "contrabands" joined the Union Army as workers or troops, forming entire regiments of the U.S. Colored Troops (USCT). Others went to refugee camps such as the Grand Contraband Camp near Fort Monroe or fled to northern cities. General Butler's interpretation was reinforced when the Congress passed the Confiscation Act of 1861, which declared that any property used by the Confederate military, including slaves, could be confiscated by Union forces.

Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863, was a powerful move that promised freedom for slaves in the Confederacy as soon as the Union armies reached them. The proclamation made the abolition of slavery an official war goal that was implemented as the Union took territory from the Confederacy. According to the Census of 1860, this policy would free nearly four million slaves, or over 12% of the total population of the United States.

Tennessee and all of the border states (except Kentucky) abolished slavery by early 1865. Some slaves were freed by the operation of the Emancipation Proclamation as Union armies marched across the South. Emancipation as a reality came to the remaining southern slaves after the surrender of all Confederate troops in spring 1865. There still were over 250,000 slaves in Texas. They were freed as soon as word arrived of the collapse of the Confederacy, with the decisive day being June 19, 1865. "Juneteenth" as celebrated in Texas, commemorates the date when the news finally reached the last slaves at Galveston, Texas. Legally, the last 40,000 or so slaves were freed in Kentucky,[7] along with a thousand or so in Delaware and West Virginia by the final ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution in December 1865.

Reconstruction to present

During Reconstruction, it was a serious question whether slavery had been permanently abolished or whether some form of semi-slavery would appear after the Union armies left.

Educational issues

The anti-literacy laws after 1831 undoubtedly contributed greatly to the widespread illiteracy facing the freedmen and other African Americans after the American Civil War and Emancipation 35 years later. After Emancipation, the unfairness of such laws helped draw attention to the problem of illiteracy as one of the great challenges confronting these people as they sought to join the free enterprise system and support themselves during Reconstruction and thereafter.

Consequently, many religious organizations, former Union Army officers and soldiers, and wealthy philanthropists were inspired to create and fund educational efforts specifically for the betterment of African Americans in the South. They helped create normal schools to generate teachers, such as those which eventually became Hampton University and Tuskegee University. Stimulated by the work of educators such as Dr. Booker T. Washington, by the first third of the 20th century, over 5,000 local schools had been built for blacks in the South with using private matching funds provided by individuals such as Henry H. Rogers, Andrew Carnegie, and most notably, Julius Rosenwald, each of whom had arisen from modest roots to become wealthy.

Apologies

On 2007-02-24 the Virginia General Assembly passed House Joint Resolution Number 728 acknowledging "with profound regret the involuntary servitude of Africans and the exploitation of Native Americans, and call for reconciliation among all Virginians."[8] With the passing of this resolution, Virginia becomes the first of the 50 united states to acknowledge through the state's governing body their state's negative involvement in slavery. The passing of this resolution came on the heels of the 400th anniversary celebration of the city of Jamestown, Virginia, which was one of the first slave ports of the American colonies.

Black slave owners

It is commonly believed that all slave owners in the United States were white. However, this was untrue. [9] The case of Anthony Johnson, a free black man who was in the first group to arrive in Virginia in 1619 as an indentured servant, and who lived in both Virginia and later Maryland as a slave owner has already been mentioned.

In 1860 there were at least six blacks in Louisiana who owned 65 or more slaves The largest number, 152 slaves, were owned by the widow C. Richards and her son P.C. Richards, who owned a large sugar cane plantation. Another black slave magnate in Louisiana, with over 100 slaves, was Antoine Dubuclet, a sugar planter whose estate was valued at (in 1860 dollars) $264,000 [10]. That year, the mean wealth of southern white men was $86,158 .[11] Still, one cannot ignore the overwhelming reality that (as the information shows above), despite these 6 black slave owners, there were millions of white slave owners.

In Charleston, South Carolina in 1860 125 free blacks owned slaves; six of them owning 10 or more. Of the $1.5 million in taxable property owned by free blacks in Charleston, approximately $300,000 represented slave holdings. In North Carolina 69 free blacks were slave owners. [12]

In 1847, a black slave owner, William Ellison, owned over 350 acres, and more than 900 by 1860. He raised mostly cotton, with a small acreage set aside for cultivating foodstuffs to feed his family and slaves. In 1840 he owned 30 slaves, and by 1860 he owned 63. His sons, who lived in homes on the property, owned an additional nine slaves. They were trained as gin makers by their father. They had spent time in Canada, where many wealthy American Blacks of the period sent their children for advanced formal education. Ellison's sons and daughters married mulattos from Charleston, bringing them to the Ellison plantation to live.[13]

In 1860 Ellison greatly underestimated his worth to tax assessors at $65,000. Even using this falsely stated figure, this man who had been a slave 44 years earlier had achieved great financial success. His wealth outdistanced 90 percent of his white neighbors in Sumter District. In the entire state, only five percent owned as much real estate as Ellison. His wealth was 15 times greater than that of the state's average for whites and thousands of times greater than most blacks.

Bibliography

Reference

- Finkelman, Paul, and Joseph C. Miller, eds. Macmillan Encyclopedia of World Slavery. 2 vol (1999)

- Rodriguez, Junius P., ed. Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion. Greenwood, 2006.

Historical studies

- Berlin, Ira. Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America. Harvard University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-674-81092-9

- Berlin, Ira and Ronald Hoffman, eds. Slavery and Freedom in the Age of the American Revolution University Press of Virginia, 1983. essays by scholars

- David Brion Davis. Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World (2006)

- Elkins, Stanley. Slavery : A Problem in American Institutional and Intellectual Life. University of Chicago Press, 1976. ISBN 0-226-20477-4, Highly controversial comparison with Nazi concentration camp life

- Fehrenbacher, Don E. Slavery, Law, and Politics: The Dred Scott Case in Historical Perspective Oxford University Press, 1981

- Fogel, Robert W. Without Consent or Contract: The Rise and Fall of American Slavery W.W. Norton, 1989. Econometric approach

- Gallay, Alan. The Indian Slave Trade (2002).

- Genovese, Eugene D. Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made Pantheon Books, 1974. one of the most influential studies; takes Marxist approach; emphasizes religion

- Genovese, Eugene D. The Political Economy of Slavery: Studies in the Economy and Society of the Slave South (1967)

- Genovese, Eugene D. and Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, Fruits of Merchant Capital: Slavery and Bourgeois Property in the Rise and Expansion of Capitalism (1983)

- Higginbotham, A. Leon, Jr. In the Matter of Color: Race and the American Legal Process: The Colonial Period. Oxford University Press, 1978. ISBN 0-19-502745-0

- Kolchin, Peter. American Slavery, 1619-1877 Hill and Wang, 1993. short survey

- Morgan, Edmund S. American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia W.W. Norton, 1975.

- Morris, Thomas D. Southern Slavery and the Law, 1619-1860 University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

- Scarborough, William K. The Overseer: Plantation Management in the Old South (1984)

- Stampp, Kenneth M. The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South (1956) influential survey

- Tadman, Michael. Speculators and Slaves: Masters, Traders, and Slaves in the Old South University of Wisconsin Press, 1989.

State and local studies

- Fields, Barbara J. Slavery and Freedom on the Middle Ground: Maryland During the Nineteenth Century Yale University Press, 1985.

- Clayton E. Jewett and John O. Allen; Slavery in the South: A State-By-State History Greenwood Press, 2004

- Kulikoff, Alan. Tobacco and Slaves: The Development of Southern Cultures in the Chesapeake, 1680-1800 University of North Carolina Press, 1986.

- Minges, Patrick N.; Slavery in the Cherokee Nation: The Keetoowah Society and the Defining of a People, 1855-1867 2003 deals with Indian slave owners.

- Mohr, Clarence L. On the Threshold of Freedom: Masters and Slaves in Civil War Georgia University of Georgia Press, 1986.

- Mooney, Chase C. Slavery in Tennessee Indiana University Press, 1957.

- Olwell, Robert. Masters, Slaves, & Subjects: The Culture of Power in the South Carolina Low Country, 1740-1790 Cornell University Press, 1998.

- Reidy, Joseph P. From Slavery to Agrarian Capitalism in the Cotton Plantation South, Central Georgia, 1800-1880 University of North Carolina Press, 1992.

- Ripley, C. Peter. Slaves and Freemen in Civil War Louisiana Louisiana State University Press, 1976.

- Rivers, Larry Eugene. Slavery in Florida: Territorial Days to Emancipation University Press of Florida, 2000.

- Sellers, James Benson; Slavery in Alabama University of Alabama Press, 1950

- Sydnor, Charles S. Slavery in Mississippi. 1933

- Takagi, Midori. Rearing Wolves to Our Own Destruction: Slavery in Richmond, Virginia, 1782-1865 University Press of Virginia, 1999.

- Taylor, Joe Gray. Negro Slavery in Louisiana. Louisiana Historical Society, 1963.

- Wood, Peter H. Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 through the Stono Rebellion W.W. Norton & Company, 1974.

Historiography

- John B. Boles and Evelyn T. Nolen, eds., Interpreting Southern History: Historiographical Essays in Honor of Sanford W. Higginbotham (1987).

- Richard H. King, "Marxism and the Slave South", American Quarterly 29 (1977), 117-31. focus on Genovese

- Peter Kolchin, "American Historians and Antebellum Southern Slavery, 1959-1984", in William J. Cooper, Michael F. Holt, and John McCardell , eds., A Master's Due: Essays in Honor of David Herbert Donald (1985), 87-111

- James M. McPherson et al., Blacks in America: Bibliographical Essays (1971).

- Peter J. Parish; Slavery: History and Historians Westview Press. 1989

- Tulloch, Hugh. The Debate on the American Civil War Era (1999) ch 2-4

Primary Sources

- Albert, Octavia V. Rogers. The House of Bondage Or Charlotte Brooks and Other Slaves. Oxford University Press, 1991. Primary sources with commentary. ISBN 0-19-506784-3

- Berlin, Ira, Joseph P. Reidy, and Leslie S. Rowlands, eds. Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, 1861-1867 5 vol Cambridge University Press, 1982. very large collection of primary sources regarding the end of slavery

- Blassingame, John W., ed. Slave Testimony: Two Centuries of Letters, Speeches, Interviews, and Autobiographies.Louisiana State University Press, 1977.

- A Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845) (Project Gutenberg: [1]), (Audio book at FreeAudio.org [2])

- "The Heroic Slave." Autographs for Freedom. Ed. Julia Griffiths Boston: Jewett and Company, 1853. 174-239. Available at the Documenting the American South website[3].

- Frederick Douglass My Bondage and My Freedom (1855) (Project Gutenberg: [4])

- Frederick Douglass Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1892)

- Frederick Douglass Collected Articles Of Frederick Douglass, A Slave (Project Gutenberg)

- Frederick Douglass: Autobiographies by Frederick Douglass, Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Editor. (Omnibus of all three) ISBN 0-940450-79-8

- Rawick, George P., ed. The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography . 19 vols. Greenwood Publishing Company, 1972. Collection of WPA interviews made in 1930s with ex-slaves

Oral histories of ex-slaves

- Before Freedom When I Just Can Remember: Twenty-seven Oral Histories of Former South Carolina Slaves, Belinda Hurmence, John F. Blair, Publisher, 1989, trade paperback 125 pages, ISBN 0-89587-069-X

- Before Freedom: Forty-Eight Oral Histories of Former North & South Carolina Slaves, Belinda Hurmence, Mentor Books, 1990, mass market paperback, ISBN 0-451-62781-4

- God Struck Me Dead, Voices of Ex-Slaves, Clifton H. Johnson ISBN 0-8298-0945-7

Historical fiction

- Edward P. Jones. The Known World New York: Amistad, 2003. ISBN 0-06-055755-9, 2003 winner of the National Book Critic Circle for fiction and 2004 winner of the Pulitzer Prize for fiction.

External links

- "John Brown's body and blood" by Ari Kelman: a review in the TLS, February 14th, 2007.

- Slavery and the Making of America - PBS - WNET, New York (4-Part Series)

- Timeline of Slavery in America

- Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers' Project, 1936-1938

- The Antislavery Literature Project major academic center for primary sources

- Images of slavery drawn by Thomas Nast (has background music)

- History of Slavery in America a historical overview

- Teaching resources about Slavery and Abolition on blackhistory4schools.com

- Slavery in the United States from EH.NET by Jenny B. Wahl of Carleton College

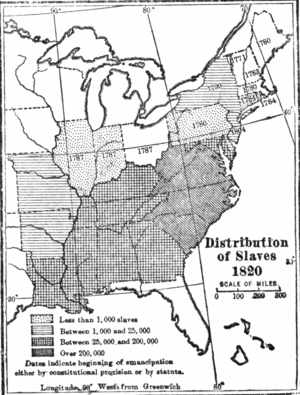

- Map of 1820 showing free and slave territories.

- Classics on American Slavery collection of old documents available on-line through Dinsmore Documentation

- Slavery: A Dehumanizing Institution by Nell Irvin Painter, historian and author of Creating Black Americans

- New Georgia Encyclopedia (Slavery in Antebellum Georgia)

- WWW-VL: Online Books on Slavery in America

- University of North Carolina Press on finding freedom and liberty in BNA-Canada

- Account of an African Prince Sold into Slavery - Islamica Magazine

- ↑ http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/ahr/105.5/ah001534.html

- ↑ Gallay, Alan. (2002) The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South 1670-171.

- ↑ Morison and Commager: Growth of the American Republicpp 212-220

- ↑ Genovese (1967)

- ↑ Genovese (1967)

- ↑ Richard S. Newman, Transformation of American abolitionism : fighting slavery in the early Republic chapter 1

- ↑ E. Merton Coulter, The Civil War and Readjustment in Kentucky (1926) pp 268-70.

- ↑ O'Dell, Larry. Virginia Apologizes for Role in Slavery, Washington Post, 2007-02-25.

- ↑ http://americancivilwar.com/authors/black_slaveowners.htm

- ↑ The Forgotten People: Cane River's Creoles of Color, Gary Mills (Baton Rouge, 1977); Black Masters, p.128.

- ↑ Male inheritance expectations in the United States in 1870, 1850-1870, Lee Soltow (New Haven, 1975), p.85.

- ↑ Black Masters: A Free Family of Color in the Old South, Michael P. Johnson and James L. Roak New York: Norton, 1984).

- ↑ http://americancivilwar.com/authors/black_slaveowners.htm