Hepatitis B virus

For the course duration, the article is closed to outside editing. Of course you can always leave comments on the discussion page. The anticipated date of course completion is May 21, 2009. One month after that date at the latest, this notice shall be removed. Besides, many other Citizendium articles welcome your collaboration! |

Classification

Higher order taxa

Virus; Retro-transcribing viruses; Hepadnaviridae; Orthohepadnavirus [1]

Species

Hepatitis B virus

Description and significance

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a member of the hepadnavirus family and causes serum hepatitis, meaning, inflammation of the liver.

Hepatitis B is one of the most common infectious diseases in the world. According to the CDC, an estimated 800,000–1.4 million people in the United States have chronic HBV infection. About 5,000 people die yearly from hepatitis-related cirrhosis and about 1,000 die from HBV-related liver cancer. This problem is even greater worldwide, approximately 350 million people are chronically infected. An estimated 620,000 people worldwide die from HBV-related liver disease each year.[2]

Depending on the patient’s immune response, infection by HBV can be asymptomatic, chronic or acute and may range from mild to severe. Many people infected with HBV never develop any symptoms and may not even know they carry the virus in their bodies; nevertheless, they are still able to pass the virus on to other people. Such people are said to be carriers of the disease.

Cell structure

The hepatitis B virus is a complex virus with a central core and a protein coat. The virions of Hepatitis B virus are 42nm in diameter and have an isometric nucleocapsid core of 27nm in diameter. This core structure is surrounded by an outer shell that is approximately 4 nm in thickness. The protein of the virion coat is known as the "surface antigen", or HBsAg, that is sometimes extended as a tubular tail on one side of the virus particle. This antigen is commonly produced in vast excesses, and can be seen in the blood of infected individuals in the form of filamentous and spherical particles. Filamentous particles are identical to the virion tails in that they vary in length and have a mean diameter of about 22nm. They sometimes display regular, non-helical transverse striations.[3]

Genome structure

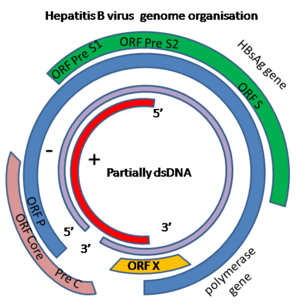

HBV is a mostly double-stranded DNA virus classified as Orthohepadnavirus within the Hepadnaviridae family. HBV causes hepatitis in human and related viruses in this family cause hepatitis in ducks, ground squirrels and woodchucks.

The genome is –RT, not segmented and contains a single circular molecule. It is partially double-stranded DNA that forms a covalently closed circle (with 5' end of the full length minus strand which is linked to the viral DNA polymerase). The complete genome is 3020-3320 nucleotides long, or 1700-2800 nucleotides long (for the full and short length strand, respectively). The genome has a guanine + cytosine content of 48 %. The genome sequence has termini with cohesive ends that match the uniquely located 5'-ends of the two strands which overlap by approximately 240 nucleotides and maintain the circular configuration of the DNA. The sequence has ENH an enhancer region and a direct repeat sequence (DR1 andDR2), or a U5-like sequence, a polyadenylated signal, and a putative glucocorticoid-responsive element; negative-sense or non-coding strand (complementary to the viral mRNA) is full-length (3.0-3.3 kb, positive sense strand (the viral mRNA) is variable in size and shorter than full-length. The double stranded genome has a nick at a unique site on full length negative strand opposite at a position 50 nucleotides, or 242 nucleotides downstream from the 5' end of the positive sense strand. The 5'-end of the negative-sense strand has a covalently attached terminal protein; positive-sense strand has a 5' capped oligoribonucleotide primer. [4]

The HBV genome has four genes: pol, env, pre-core and X that respectively encode the viral DNA-polymerase, envelope protein, pre-core protein (which is processed to viral capsid) and protein X. The specific function of protein X is not clear but it may be involved in the activation of host cell genes and the development of malignant cells.[5]

Ecology and Transmission

Hepatitis B virus is normally transmitted through blood transfusions, contaminated equipment, drug users' unsterile needles, or any body secretion (saliva, sweat, semen, breast milk, urine, feces). The virus also can pass from the blood of an infected mother through the placenta to infect the fetus.

Note: an image will soon be uploaded for this section. Also, a section about the life cycle of HBV will be added.

Pathology

HBV may cause acute and chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, immune complex disease, polyarteritis, glomerulonephritis, infantile papular acrodermatitis and aplastic anemia. An asymptomatic carrier state with high viremia may develop particularly after perinatal infection or under immune suppression.

The chances of becoming chronically infected depends upon age. About 90% of infected neonates and 50% of infected young children will become chronically infected. In contrast, only about 5% to 10% of immunocompetent adults infected with HBV develop chronic hepatitis B. In some individuals who become chronically infected, especially neonates and children, the acute infection will not be clinically apparent.

Acute hepatitis B can range from subclinical disease to fulminant hepatic failure in about 2% of cases. Many acutely infected individuals develop clinically apparent acute hepatitis with loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, fever, abdominal pain and jaundice. In cases of fulminant hepatic failure from acute HBV infection, orthotopic liver transplantation can be life-saving. About 90% to 95% of acutely infected adults recover without sequelae. About 5% to 10% of acutely infected adults become chronically infected.

The natural history of chronic HBV infection can vary dramatically between individuals. Some will develop a condition commonly referred to as a chronic carrier state. These patients, who are still potentially infectious, have no symptoms and no abnormalities on laboratory testing. Nonetheless, some of these patients will have evidence of hepatitis on liver biopsy.

Some individuals with chronic hepatitis B will have clinically insignificant or minimal liver disease and never develop complications. Others will have clinically apparent chronic hepatitis. Some will go on to develop cirrhosis. Individuals with chronic hepatitis B, especially those with cirrhosis but even so-called chronic carriers, are at an increased risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma (primary liver cancer). Although this type of cancer is relatively rare in the United States, it is the leading cause of cancer death in the world, primarily because HBV infection is endemic in the East.

Chronic infection with HBV can be either "replicative" or "non-replicative." In non-replicative infection, the rate of viral replication in the liver is low and serum HBV DNA concentration is generally low and hepatitis Be antigen (HBeAg) is not detected. HBeAg is an alternatively processed protein of the pre-core gene that is only synthesized under conditions of high viral replication. In "replicative" infection, the patient usually has a relatively high serum concentration of viral DNA and detectable HBeAg. Patients with chronic hepatitis B and "replicative" infection defined by the presence of detectable HBeAg have a generally worse prognosis and a greater chance of developing cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma than those without HBeAg. In rare strains of HBV with mutations in the pre-core gene, "replicative" infection can occur in the absence of detectable serum HBeAg.

In its most serious forms, hepatitis B can be a life-threatening disease. The virus causes severe scarring of the liver. The scarring process is called cirrhosis (pronounced suh-RO-suss) of the liver. Cirrhosis damages the liver so badly that it may no longer be able to function normally. It can cause the death of the patient. Cirrhosis can also lead to liver cancer (see cancer entry).

Current research

October 2002, Vol 92, No. 10 | American Journal of Public Health 1619-1628 Chinese Herbal Medicine and Interferon in the Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis B: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized, Controlled Trials

A study conducted by the University of California at Berkley showed that a new Chinese-herbal treatment may be beneficial to treatment of chronic hepatitis B. The researchers compared changes in three markers of infection (HBsAg, HBeAg, and HBV) as a result of three types of treatments: Chinese herbal medicine alone, Chinese herbal treatment in conjugation with interferon alfa, and interferon alfa alone. The results showed that combination of Chinese herbal treatments with interferon alfa were 1.5 to 2 times more effective as interferon alfa in reducing the hepatitis B viral load to undetectable level for all three measure of infection. The herbal treatments used for this study included mixtures of bufotoxin (an extract from the skin of the toad bufo gargarizans) and kurorinone (an extract from the root of the pant sophorae flavescentis). Although the quality of this studty was poor, these data suggest that further trials of Chinese Herbal Medicine and interferon in chronic hepatitis B infection are justified.

References

[1] http://www.uniprot.org/taxonomy/489460

http://phene.cpmc.columbia.edu/ICTVdB/00.030.0.01.003.htm

http://www.comeunity.com/adoption/health/hepatitis/smith.html

http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/imagepages/1031.htm

http://pathmicro.med.sc.edu/virol/hepatitis-virus.htm

http://www.faqs.org/health/Sick-V2/Hepatitis.html

http://www.ajph.org/cgi/content/full/92/10/1619

- Please note, all sections will be further modified.