Fall of South Vietnam: Difference between revisions

John Leach (talk | contribs) m (Text replacement - "EAGLE PULL" to "Eagle Pull") |

John Leach (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ | {{PropDel}}<br><br>{{subpages}} | ||

{{ | |||

The [[Paris Peace Talks|Paris Peace Accords]] of January 27, 1973, were the beginning of the end of [[South Vietnam]]. There would be an immediate in-place permanent cease-fire. The U.S. agreed to withdraw all its troops in 60 days (but could continue to send military supplies); North Vietnam was allowed to keep its 200,000 troops in the South but was not allowed to send new ones. | The [[Paris Peace Talks|Paris Peace Accords]] of January 27, 1973, were the beginning of the end of [[South Vietnam]]. There would be an immediate in-place permanent cease-fire. The U.S. agreed to withdraw all its troops in 60 days (but could continue to send military supplies); North Vietnam was allowed to keep its 200,000 troops in the South but was not allowed to send new ones. | ||

Revision as of 23:12, 1 April 2024

| This article may be deleted soon. | ||

|---|---|---|

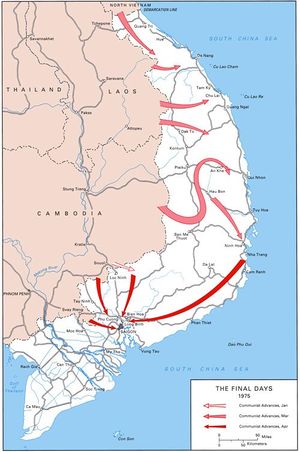

The Paris Peace Accords of January 27, 1973, were the beginning of the end of South Vietnam. There would be an immediate in-place permanent cease-fire. The U.S. agreed to withdraw all its troops in 60 days (but could continue to send military supplies); North Vietnam was allowed to keep its 200,000 troops in the South but was not allowed to send new ones. While some of the 1975 attack that overthrew the Republic of Vietnam came directly from the North, even those attacks had come from areas under the Provisional Revolutionary Government, which was under the effective control of the North Vietnamese governing Politburo. Other attacks came from areas under PRG control, near Saigon, which had started from sanctuaries inside Cambodia. To carry out these attacks, the People's Army of Viet Nam had been learning how to conduct not only command and control at a true corps level, but how to manage the operational art of simultaneous operations by multiple corps-level organizations. In contrast, South Vietnamese military had unclear goals, even on operational issues of when to trade territory for time. It had not learned to exercise command and control at the level of a national effort. While it had officially changed the term "corps tactical zone (CTZ)" to "military regions (MR)", there were still four largely autonomous organizations, although they could request strategic reserves from the Joint General Staff. [1] While airpower advocates can be overconfident about their capability to do battlefield air interdiction and deep strategic strike, the opportunity never arose for the South Vietnamese air force. Control of air assets was always decentralized to the CTZ/MR level; there was no headquarters capable of organizing a mass air attack on North Vietnamese logistical centers. Correlation of ForcesWhile the PAVN and ARVN had approximately the same number of troops, the ARVN, needing to support a fixed defensive system as well as its mobile combat forces, could field 13 operational divisions compared to 18 in the ARVN. Flexible defenseThe aforementioned strategic reserves tended to kept close to Saigon as a protection against internal military coups; the fear of a coup often led President Thieu to rate loyalty higher than proficiency. At the division and corps level, the quality of leadership was very uneven. As it was, some of the existing strategic reserve, specifically the Airborne and Marine Divisions, had become committed to the static defense of the northern provinces in MR I. An attempt was made to reorganize to create new reserves in 1974, but was only of limited success. President Nguyen Van Thieu, who came from the military, still made detailed decisions and wanted to defend everywhere, even without the resources to do so. It is a classic military axiom that "he who defends everywhere defends nowhere"; a realistic defense must have mobile reserves, even if they can be made available only by giving up land. In addition to lacking strategic reserve troops, South Vietnam did not plan for systematic military and civilian evacuation of areas that might need to be abandoned, as part of the classic military approach of trading land for time. Not only were there no evacuation routes for the rear; there were no coherent plans to have routes and logistical support for reserve units to move to the new fronts. Comparative resourcesWhile U.S. troops were gone, U.S. funding for South Vietnam, and resupply, had drastically decreased. The PAVN, however, had been getting abundant resources from the Soviet Union and China. Due to a lack of spare parts, 30 to 40 percent of ARVN equipment was inoperative on any given day, while ammunition shortages cut fire support capabilities by 60 percent. [2] While individual ARVN units fought well, command and control at the corps and national level was poor. There really was no national planning; each of the corps commanders was responsible for ground, naval, and air forces in his area. Their air force, under the control of army corps commanders, rather than under a central command, never was able to plan and conduct the use of mass to interdict the attacking forces, especially in their rear. [3] They never conducted an air campaign to mass air power and interdict the communist offensive forces. The Decision to InvadeIn December 1974, the North Vietnamese Politburo gave command of the main assault to GEN Van Tien Dung, whose patron was Vo Nguyen Giap. Dung had been the chief of staff and head of logistics at Dien Bien Phu, and was considered a solid but not brilliant leader. [4] This would still take the form of several phases before the final large-scale attack, which was called the Ho Chi Minh campaign. Even in that attack, the PAVN adjusted to changing conditions; they did not expect the chaotic defense and partial collapse with which they were faced. PreliminariesIn January, the PAVN 301st Corps began a multidivision operation in Tay Ninh Province, north of Saigon.[5] First, a diversionary attack was made at Tay Ninh; LTG Du Quoc Dong, used his reserve to defend enemy's attack on Tay Ninh. Initial requests for strategic reserve (airborne and marine) troops were at first refused by President Thieu, but, on January 5, 250 Rangers from the 81st airborne Rangers made an air assault to reinforce Phuoc Long City. Without air, artillery, or armored support, they failed to reach their destination, and Phuoc Long City surrendered on the 6th. The main attack, on December 13, involved the 3rd and 7th Infantry Divisions, with a tank battalion, an artillery regiment, an antiaircraft regiment, and sapper units under corps control. The NVA 7th Infantry Division moved towards Bo Duc, Don Luan, and Phuoc Long City, with the 3rd Infantry Division simultaneously moving to capture Duc Phong, and Phuoc Long City. Phuoc Binh airfield and the main firebase were suppressed by artillery, and the isolated garrisons destroyed individually. The attack isolated the province by cutting National Highway 14. The PAVN were not impressed by the alerting of U.S. Marines on Okinawa, and the moving of an aircraft carrier into range. [6] Thieu told the cabinet that while it could be taken back, it would not be worthwhile, although GEN Cao Van Vien, chief of the Joint General Staff, warned that it would encourage the North Vietnamese. The RVN Air Force had performed poorly there, losing 20 aircraft to groundfire yet not pressing in to hit targets accurately. [7] Even after the U.S. did not respond with the B-52 strikes, expected by the South Vietnamese leadership, major general Homer Smith, the U.S. Defense Attache (i.e., the senior U.S. military officer still in South Vietnam) said they kept waiting for U.S. support, having great difficulty in believing it would not come. [8] After this result, Le Duan personally told the Politburo that the next step should be to move against Darlac Province and its capital, Ban Me Thuot, and then toward the sea. From the Politburo meeting, Le Duc Tho took the idea to the senior military committee, where Vo Nguyen Giap joined the discussion, agreeing generally but wanting a deceptive move, as well, against Tai Nguyen. Dung left for his field headquarters on February 5. The basic operational plan mirrored that which preceded the Battle of the Ia Drang: drive through Central Vietnam to the sea, cutting South Vietnam in half. One important difference from 1966-7 was that the PAVN had mobile air defenses including anti-aircraft artillery and surface-to-air missiles. Retreat in I Corps tactical zoneWhile the I Corps tactical zone, closest to North Vietnam, had the largest number of ARVN troops, the national command did not think they could hold it. There had been artillery duels and conventional fighting since 1974, and PAVN forces had established firebases from which they closed the Hue airport. The artillery positions closing the airfield were only retaken on January 10, yet when new construction and large convoys were observed in mid-February, the corps commander would not authorize artillery fire to be used against them. On March 8, PAVN forces launched offensives north and south of Hue, threatening Highway 1, although the ARVN was able to force them back in two days.[9] The Airborne was under orders to evacuate on March 10, and return to the strategic reserve in Saigon. This was to have been a controlled maneuver, with the Marine regiments moving to cover the ground that the Airborne had held. First operational phaseFacing forces under Pham Van Phu, the PAVN feinted at Pleiku, as during the Ia Drang campaign, but sent their main, three-division attack at Ban Me Thuot, surrounding it on March 9, and withstanding a counterattack on March 14, taking the city. [10] The main assault was farther south than in the 1966-1967 campaign. There was strategic surprise on both sides. The South Vietnamese had not been expecting a major invasion, and assumed, much as in 1972, that the U.S. would assist if one did take place. The North Vietnamese were surprised by the lack of resistance, especially the chaos following the fall of Ban Me Thuot. [11] BreakoutFrom Ban Me Thuot, the PAVN moved north towards Pleiku and southeast, across Highway 25 towards the coastal town of Tuy Hoa; capture of Tuy Hoa split South Vietnam in half.[12] Thieu ordered Phu to abandon Pleiku and Kontum and form a new defense line; Phu abandoned his command post; [13] he committed suicide in Saigon when it fell on April 30. Perhaps 200,000 refugees, without any leadership or support, could only use Highway 7, partially overgrown and with broken bridges, to try to escape to the coast. As they moved, the NVA 320B Division attacked their rear. [14] Thieu then changed from the "light at the top" plan, demanding Hue be held to the last. National Highway 1, the only road out of Hue, however, had been blocked by the PAVN, as they came across and captured Tuy Hoa. Hue-Danang movementMeanwhile, the PAVN hit attacked at multiple points along the seacoast such Chu Lai, Quang Ngai. Hue was cut off by March 24, LTG Ngo Quang Truong did not understand President Thieu's intent to hold Hue at all costs and he ordered the city abandoned on March 25.[15] With Hue captured, the NVA sent four divisions against Da Nang. An ARVN equivalent of Dunkirk evacuated only 16,000 soldiers out of 70,000 in the area. The base, not strongly defended, fell on March 29. Equipment losses at Danang alone included hundreds of tons of ammunition and 180 aircraft. This set the final campaign, attacking Saigon. CIA officer Frank Snepp believed Nguyen Van Thieu was keeping reserve forces close to Saigon for protection against coups, rather than as military reserves. While CIA intelligence sources in central Vietnam were, at this point, nonexistent. Snepp briefed Ambassador Graham Martin and CIA Station Chief Thomas Polgar that this was the Communists' final, all-out effort, but they considered him pessimistic.[16] At this point, for many reasons, the immense southward flow of refugees was South Vietnam's chief problem. It was, of course, a humanitarian tragedy; there were no facilities to feed or treat refugees. From a cold military standpoint, however, it also blocked the roads, so, even when an ARVN unit retreated in good order, it had great difficulty linking up with other ARVN forces, so the ARVN had real problems in creating new defensive lines. The southern PAVN advance split into two columns moving south from Dong Ha, one moving on either side of the Truong Son mountains, and the other continuing south on National Highway 1. South Vietnamese appeals for U.S. supportPresident Thieu released written assurances, dated April 1973, from President Nixon that the U.S. would "react vigorously" if North Vietnam violated the truce agreement. Nixon had resigned in August 1974 and his personal assurances were meaningless; After Nixon made the promises, Congress had prohibited the use of American forces in any combat role in Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam without prior congressional approval. This was well known to the Saigon government, but the leadership, not understanding American politics, refused to believe it, thinking the U.S. Congress was as powerless as their National Assembly. [17] The Ford Administration, with specific legislative restrictions against direct aid and a lack of public support, was limited to some financial aid. "Ho Chi Minh campaign"The Politburo directed Dung to "liberate" the south before the monsoon season in May. This was to be called the "Ho Chi Minh campaign"; that term sometimes has been used for the entire invasion, but it seems more specific to the push on Saigon. PAVN GEN Dung obtained information that the ARVN would form their main defensive line at Phan Rang, south of Cam Ranh Bay, in the III Corps tactical zone.[18] Clearing the approachesTo get access to the Saigon area and its outer defenses, Xuan Loc was seen as a key point, controlling five major roads:[19]

It was a difficult defensive problem; the main blocking positions ranged from 17 to 30 miles from the Saigon boundary, and there really were not enough troops to hold a cohesive ring. The ring could had to be wide enough to keep Saigon out of the range of the Soviet 130mm guns, approximately 17.5 miles. Also, there were several key bases in the wider area that were part of the overall South Vietnamese defense:

BG Ly Tong Ba commanded the final defense of Cu Chi, being surrounded in a fighting retreat to Hoc Mon.[20] ARVN units defending Xuan Loc performed extremely well. The division defending it threw back a three-division PAVN corps in early April. A second attack, beginning on April 9, began frontal tank and infantry assaults against the 18th Division, now reinforced with a regiment of the 5th Division and the 1st Airborne Brigade. They held for two weeks, and then fought a disciplined retreat as the PAVN tried to encircle them from both flanks. During that time, President Nguyen Van Thieu resigned, his vice-president briefly stepped up, and Gen. Duong Van Minh became the final President. Nevertheless, the PAVN captured this key road junction on April 21.[21] Attacking Saigon properGEN Dung did not intend to seize Saigon house-by-house, but had five major objectives for his 16 division force:

Once these points were taken, they would then move outward into the city, as the tactical situation required, but taking these points would effectively cut the head from the ARVN's neck. Early in the morning of April 30, the PAVN attacked. Resistance was slight and ineffective. Tanks quickly broke down the gates of the presidential palace, where Duong Van Minh, known as "Big Minh", tried to surrender. PAVN Senior Colonel Bui Tin refused his surrender, saying "you cannot give up what you do not have." EvacuationOperation Eagle Pull evacuated Americans from Cambodia on April 12. Dung assumed this was a practice run for an evacuation of Vietnam, which boosted PAVN morale.[22] About 140,000 refugees managed to flee the country, chiefly by boat. The PAVN then concentrated its combat power to attack the six ARVN divisions isolated in the north. After destroying these divisions, the PAVN launched its "Ho Chi Minh Campaign" that with little fighting seized Saigon on April 30, ending the war.[23] No American military units had been involved until the final days, when Operation FREQUENT WIND was launched to protect the evacuation of Americans and 5600 senior Vietnamese government and military officials, and employees of the U.S. The 9th Marine Amphibious Brigade would enter Saigon to evacuate the last Americans from the American Embassy to ships of the Seventh Fleet.[24] The endVietnam was unified under Communist rule, as nearly a million refugees escaped by boat. Saigon was renamed Ho Chi Minh City. Even a unified Vietnam, however, had not seen the end of war. Even though both sides were Communist, there had been skirmishing, in Cambodia, between PAVN and Khmer Rouge forces since 1973. Within the Communist world, no longer unified, Vietnam was principally backed by the Soviet Union, the Khmer Rouge was supported by China. The Third Indochina War escalated when Vietnam invaded Cambodia in 1978, and China countered by invading northern Vietnam in 1979. References

|

||