Bonny Hicks: Difference between revisions

imported>Stephen Ewen (update) |

imported>Stephen Ewen |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

==Background and modeling== | ==Background and modeling== | ||

{{Image|Bonny-hicks-go-mag-1987.jpg|thumb|188px|Hicks in 1987, on the magazine cover that launched her modeling career.}} | |||

Hicks was born in [[Kuala Lumpur]], [[Malaysia]], to a British father and a Singaporean-[[Han Chinese|Chinese]] mother. She identified her formative [[social environment]] as a [[multi-ethnic]] and [[multi-lingual]] environment that included [[Malays in Singapore|Malays]], [[India]]ns and Chinese of various [[dialect group]]s.<ref name="tu">{{cite web|title=Celebrating Bonny Hicks' Passion for Life|accessdate = 2006-12-27|publisher=Harvard University|year=1998|author=Tu Wei-Ming|url=http://www.zaobao.com/bilingual/pages/bilingual221298.html|archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20051121022527/http://www.zaobao.com/bilingual/pages/bilingual221298.html|archivedate=2005-11-21}}</ref> When Hicks was 12, her mother accepted a job as a caretaker of a [[bungalow]] in [[Sentosa]] and they relocated to the island away from a Singaporean [[Housing and Development Board]] flat in [[Toa Payoh]].<ref name="tnp20">{{cite news|last=Maureen|first=Koh|title=Mum spends birthdays at crash site|location=Singapore|publisher=The New Paper|date=2008-08-26}}</ref> Throughout her teens, she lived with her mother on Singapore's [[Sentosa Island]],<ref name="mermaid">{{cite web|url=http://www.scholars.nus.edu.sg/post/singapore/literature/poetry/chia/mermaid.html|title=Mermaid Princess|accessdate = 2006-12-27|publisher=The Literature, Culture, and Society of Singapore|year=1998|author=Grace Chia}}</ref> and intermittently with her ''porpor'' (grandmother), with whom she enjoyed a particularly close relationship.<ref name="truth">Tan Gim Ean, "A Bonny way to tell the truth" ''New Straits Times'', 30 May 1992, 28.</ref> At one point, aged 16, Hicks traced her father through the [[British High Commission]]. He wanted nothing to do with her, she was informed, and the two never met.<ref name="covgirl">{{cite web|url=http://www.limrichard.com/arc1997/arch_c2.htm|title=Cover Girl from first to last|accessdate = 2006-12-29|publisher=The Straits Times (Singapore)|date=28 December 1997|work=Life Section}}</ref><ref name="covergirl">Rahman, Sheila, "Don't judge a covergirl by her looks," ''New Straits Times'', 2 Sept 1990, 10.</ref> | Hicks was born in [[Kuala Lumpur]], [[Malaysia]], to a British father and a Singaporean-[[Han Chinese|Chinese]] mother. She identified her formative [[social environment]] as a [[multi-ethnic]] and [[multi-lingual]] environment that included [[Malays in Singapore|Malays]], [[India]]ns and Chinese of various [[dialect group]]s.<ref name="tu">{{cite web|title=Celebrating Bonny Hicks' Passion for Life|accessdate = 2006-12-27|publisher=Harvard University|year=1998|author=Tu Wei-Ming|url=http://www.zaobao.com/bilingual/pages/bilingual221298.html|archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20051121022527/http://www.zaobao.com/bilingual/pages/bilingual221298.html|archivedate=2005-11-21}}</ref> When Hicks was 12, her mother accepted a job as a caretaker of a [[bungalow]] in [[Sentosa]] and they relocated to the island away from a Singaporean [[Housing and Development Board]] flat in [[Toa Payoh]].<ref name="tnp20">{{cite news|last=Maureen|first=Koh|title=Mum spends birthdays at crash site|location=Singapore|publisher=The New Paper|date=2008-08-26}}</ref> Throughout her teens, she lived with her mother on Singapore's [[Sentosa Island]],<ref name="mermaid">{{cite web|url=http://www.scholars.nus.edu.sg/post/singapore/literature/poetry/chia/mermaid.html|title=Mermaid Princess|accessdate = 2006-12-27|publisher=The Literature, Culture, and Society of Singapore|year=1998|author=Grace Chia}}</ref> and intermittently with her ''porpor'' (grandmother), with whom she enjoyed a particularly close relationship.<ref name="truth">Tan Gim Ean, "A Bonny way to tell the truth" ''New Straits Times'', 30 May 1992, 28.</ref> At one point, aged 16, Hicks traced her father through the [[British High Commission]]. He wanted nothing to do with her, she was informed, and the two never met.<ref name="covgirl">{{cite web|url=http://www.limrichard.com/arc1997/arch_c2.htm|title=Cover Girl from first to last|accessdate = 2006-12-29|publisher=The Straits Times (Singapore)|date=28 December 1997|work=Life Section}}</ref><ref name="covergirl">Rahman, Sheila, "Don't judge a covergirl by her looks," ''New Straits Times'', 2 Sept 1990, 10.</ref> | ||

Revision as of 03:31, 20 July 2010

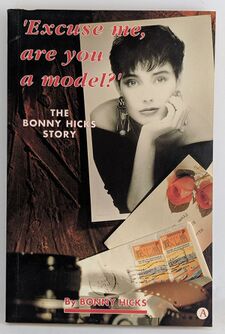

Bonny Hicks (5 January 1968 – 19 December 1997) was a Singaporean model who gained her greatest notoriety for her contributions to Singaporean post-colonial literature and the anthropic philosophy conveyed in her works. Her first book, Excuse Me, are you a Model?, is recognized as a significant milestone in the literary and cultural history of Singapore.[1] She followed it with Discuss Disgust and many shorter pieces in press outlets. She was killed at age twenty-nine on 19 December 1997 when SilkAir Flight 185 crashed into the Musi River on the Indonesian island of Sumatra, killing all 104 on board.[2] After her death special publications, including the book Heaven Can Wait: Conversations with Bonny Hicks by Tal Ben-Shahar, eulogized her. Widely deemed controversial during her lifetime for her willingness to openly discuss human sexuality, her legacy is now understood as important within particularly Singaporean society.

Background and modeling

Hicks was born in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, to a British father and a Singaporean-Chinese mother. She identified her formative social environment as a multi-ethnic and multi-lingual environment that included Malays, Indians and Chinese of various dialect groups.[3] When Hicks was 12, her mother accepted a job as a caretaker of a bungalow in Sentosa and they relocated to the island away from a Singaporean Housing and Development Board flat in Toa Payoh.[4] Throughout her teens, she lived with her mother on Singapore's Sentosa Island,[5] and intermittently with her porpor (grandmother), with whom she enjoyed a particularly close relationship.[6] At one point, aged 16, Hicks traced her father through the British High Commission. He wanted nothing to do with her, she was informed, and the two never met.[7][8]

After completing her A levels,[7] Hicks was "discovered" at age 19 by Patricia Chan Li-Yin ("Pat Chan"), a nationally decorated female swimmer-turned-agent.[9] Hicks and Chan enjoyed a special relationship that was certainly multi-leveled, and a complicated mix of the professional and personal. Stemming from ambiguous statements Hicks later made in her first book, speculation was widespread over whether the two had become sexually involved. While Hicks' statements in her book could be interpreted as stemming from only an intimate mentoring relationship with Chan, Hicks continued to be ambiguous on the matter whenever questioned, if only to encourage ongoing buzz and publicity.[8]

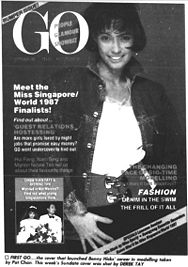

Hicks' modeling career began with the September 1987 cover of a popular Singaporean fashion monthly. She followed it with scores of other covers, upwards of thousands of ads, and catwalks featuring designer clothes. Just a year into her modeling career, Hicks began writing about her life experiences and ideas surrounding her modeling, and by age 21, she had completed her first book, 'Excuse Me, are you a Model?'[3] She continued to model until aged 24, a total of five years, when coinciding with the 1992 release of her second book, Discuss Disgust, she left modeling to take a job as a copywriter in Jakarta, Indonesia. At that time, Hicks clearly stated what she had only hinted at before, that she had never wanted to be a model in the first place.[10] Since age 13, her dream was instead to be a writer, and it was at that time that she began keeping a diary of her feelings and experiences, a practice she frequented during various times throughout life.[8][6]

Before her move to Indonesia, Hicks was married briefly to a former member of the Republic of Singapore Air Force. She left him for Richard "Randy" Dalrymple, an American architect, by whose side she died.[11]

Literary contributions

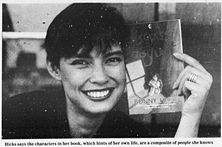

Hicks' first work, 'Excuse Me, are you a Model?', was published in Singapore in 1990. The book is Hicks' autobiographical exposé of the modeling and fashion world and contains frequent candid discussion from Hicks about her sexuality, a subject not traditionally broached in Singaporean society. The work stirred significant controversy among those with traditional literary and moral standards in Singapore, who considered it a "kiss and tell" book and "too much too soon" from a woman barely into her twenties. Singaporean youth, on the other hand, had a starkly different view. In just three days they bought up 12,000 copies, and after two weeks, 20,000 copies, prompting the book's publisher to declare Hicks' work "the biggest book sensation in the annals of Singapore publishing".[12] During the years leading up to Hicks' death, Singaporean English literature scholars had begun to recognize more than just a simple generational divide in the reactions to Hicks' book, and were describing it as "an important work" in the "confessional mode" of the genre of post-colonial literature,[13] and "a significant milestone in Singapore’s literary and cultural history". By then, Singaporean young people had already established a localized literary movement, following Hicks' lead. Local markets proliferated with the autobiographies of youth, some not yet in their twenties.[1]

In 1992, two years after Hicks' much publicized entry into Singapore's literary scene, she published her second and last book, Discuss Disgust, wherein she continued to broach issues not traditionally spoken of openly in Singapore. The novella, arguably more serious but never as popular as her first book, portrays the world as seen through the eyes of a child whose mother is a prostitute, and is Hicks' semi-autobiographical account of her troubled childhood years.[14] [15] Continuing on with the controversy surrounding Hicks' writings, one traditionalist reviewer dubbed it "another one of those commercial publications which pack sleaze and sin into its hundred-oddpages."[16] At the time of Discuss Disgust's release, Hicks reported to the New Straits Times that she had been working on a third book, one that centered on a series of correspondence between her and a housemate whom she left unnamed. Hicks wrote of her social observations of the United States while on a two-month visit, while her housemate springboarded into social commentary about Singapore.[6]

Hicks was also a frequent contributor to the Singaporean press and other outlets.[3] Her frankly-written bi-monthly column in The Straits Times, "The Bonny Hicks Diary," in which she often discussed her childhood on Sentosa Island, further incited critics over feelings that Hicks was an improper role model for young, impressionable girls. Yielding to the pressure, the Times pulled her column after not even a year, although it continued to run other pieces by Hicks on occasion, noting a deepening of thought in them.[7]

Philosophy

Beneath the controversy, Hicks' anthropical philosophy of life that featured loving, caring and sharing, emerged clearly in her writings, and attracted the attention of many Singaporeans and others, including scholars.[3]

Until her 1997 death, Hicks carried on an approximately year-long correspondence about philosophical and spiritual matters with Tal Ben-Shahar, a positive psychologist and popular professor of psychology at the time at Harvard University. The correspondence later became basis for a 1998 book by Ben-Shahar.[3]

Hicks had also became a serious student of Confucian humanism, and she was particularly attracted to the thought of another Harvard professor, Tu Wei-Ming, a New Confucian philosopher. Hicks attended Tu's seminars and the two carried on a series of correspondence. With Tu's influence added to that of Ben-Shahar's, Hicks began to exhibit an increased New Confucian influence upon her thinking, and soon turned in her occasional columns to criticizing Singaporean society from the theme. In one piece, she expressed dismay about the "lack of understanding of Confucianism as it was intended to be and the political version of the ideology to which we [as Singaporeans] are exposed today". Just prior Hicks' death she had submitted perhaps her most mature column ever to Singapore's The Straits Times. The daily posthumously published "I think and feel, therefore I am", on 28 December 1997. [3] In it Hicks argued that

Thinking is more than just conceiving ideas and drawing inferences; thinking is also reflection and contemplation. When we take embodied thinking rather than abstract reasoning as a goal for our mind, then we understand that thinking is a transformative act.

The mind will not only deduce, speculate, and comprehend, but it will also awaken, will, enlighten and inspire.

Si, is how I have thought, and always will think.[3]

Tu asserts that Hicks' use of the Chinese character Si was "code language," readily understood by her Chinese-speaking English readers, to convey New Confucian thought. The piece, Hicks' last, reflects the maturing and deepening engagement in philosophy and spirituality that she had clearly been enveloped in during the last year of her life.[3]

Future plans and crash

When Hicks initially set out, she had wanted to write a book to which people would react. Whether those reactions were positive or negative was not her first concern. Only public indifference, the antithesis of public reaction, would impede her achievement of fame and popularity, she believed, a message Pat Chan had certainly stressed to her from the start. And to be sure, scant few found themselves able to respond to Hicks with a mere shrug. Yet Hicks had not anticipated the intensity of the negative reactions, had not surmised the toll that the negative words and societal shunning would take over time upon her psyche. In many ways, her move to Indonesia, which coincided with the release of her second book, was an attempt to escape the intense controversy she had experienced in Singapore over her first book. Her hope was to find a place away from the heat where she could deepen and further redefine herself before, perhaps, a larger relaunching of herself in her native homeland and, hopefully, internationally.[3][8]

Part of Hicks plan was to attend university. She frequently expressed regret that she had not studied past her A-levels. During the year leading up to her 1997 death, she applied to numerous universities in England and the United States, including Harvard University. Certainly, her Harvard mentors exerted influence on her behalf during this process, which no doubt helped overcome any affects remaining from Hicks' unremarkable academic record. By this time, Hicks could present herself as a fascinating and exceptional if not ideal candidate to any school she wished to attend: a young woman who overcame a difficult upbringing to become a nationally known model-turned-author, and whose mind and insights had authentically impressed the high-level academicians who had written letters of uncommon detail and enthusiasm in support of her candidacy. Hicks soon reported that she had received one university acceptance, refusing to say where, and was awaiting other possible acceptances before ultimately deciding where to attend.[3][7]

Hicks had also thought to mature her image by marrying, settling down, and hopefully having children. Shortly before her death, Hicks became engaged to her longtime boyfriend, Richard "Randy" Dalrymple, an American architect of some prominence because of his unique structures in Singapore and Jakarta. It was to celebrate Christmas with Dalrymple's family that Hicks and Dalrymple boarded SilkAir Flight 185 in Jakarta for the United States, probably their first visit as an engaged couple. Less than thirty minutes into the flight, from 35,000 feet, the plane began a sudden high-speed nosedive at an almost direct incline toward the Musi River. The plane reached such high velocity that it broke into pieces before scattering across the surface. Local fisherman immediately searched the crash site for survivors but did so in vain. Both Hicks and Dalrymple perished, along with all others aboard. Not a single body, not even so much as one complete limb, was found intact.[11][17][18]

Aftermath of death

Hicks' death at the age of 29 shocked Singaporeans and others worldwide, and prompted a swirl of activity as people sought to interpret the meaning of a life that had been suddenly cut short. Meanwhile, investigators probed the causes of SilkAir Flight 185's crash.

No part of Hicks' body was ever found, only her wallet and credit cards. The crash had occurred with such tremendous force that only 6 of the 104 victims could be identified from partial remains.[19]

As the crash investigations continued, investigators discovered that Hicks' ex-husband was a Republic of Singapore Air Force friend of Tsu Way Ming, the Singaporean captain of SilkAir Flight 185. Tsu was said to loathe Hicks for deserting his colleague, and according to the flight recorder, had walked into the plane's cabin shortly before the crash. There he was thought to have disabled the plane's flight recorder, and while there, it would have been hard for him to miss Hicks and her new fiancé seated together in first-class. Investigators additionally discovered that Tsu had not only longstanding personal problems and a string of troubling incidents as a pilot, but leading up to the time of the crash, had been experiencing serious family and financial problems, in part due to his gambling. He had also taken out a large life insurance policy on himself that went into effect the very day of the crash.[19]

As answers and unanswered questions continued to trickle out from the flight investigations, literary scholars both in Singapore and elsewhere had already begun examining Hicks' works anew, some for the first time.

Tu Wei-Ming characterized Hicks' life and philosophy as providing a "sharp contrast to Hobbes' cynic[al] view of human existence", and stated that Hicks was "the paradigmatic example of an autonomous, free-choosing individual who decided early on to construct a lifestyle congenial to her idiosyncratic sense of self-expression." More than anything, Tu said, "She was primarily a seeker of meaningful existence, a learner."[1][13][15]

Singaporean post-colonial author Grace Chia eulogized Hicks' life in a poem, "Mermaid Princess", that parodies the traditional Scottish folk song, "My Bonnie Lies over the Ocean". An excerpt of the poem characterizes Hicks as one who

The Straits Times eulogized Hicks by recalling her life and contributions to the paper, and by publishing an excerpt of the famous essay "Whistling Of Birds" by D. H. Lawrence. The Straits Times' began its piece with a line from the famous folk/rock song Fire and Rain by James Taylor. "Sweet dreams and flying machines, and pieces on the ground" seemed to perfectly encapsulate much of the retrospective public feeling about Hicks' life and sudden death.[7]

On the first anniversary of Hicks' death, in December 1998, Tal Ben-Shahar published Heaven Can Wait: Conversations with Bonny Hicks, in which he weaved together his and Hicks' year-long correspondence with his own philosophical musings. The book is described as an extended postmodern "conversation" between two seekers intensely journeying together in a quest for meaning and purpose, and takes its title from a piece Hicks had submitted to The Straits Times just days before her death, which ever after took on a hauntingly prophetic air. In it she wrote, "The brevity of life on earth cannot be overemphasized. I cannot take for granted that time is on my side—because it is not ... Heaven can wait, but I cannot".[21][22] In an earlier piece that memorialized her grandmother, Hicks confessed that she believed in life after death.[3]

By this time, the crash investigations were complete. Indonesian authorities concluded that the crash had occurred for unknown reasons, resulting in widespread criticisms that they had politicized their report so as to not harm their fledgling national airline industry by striking fear into potential passengers. Joining the criticism, U.S. authorities confidently, and with rare brushes of rhetorical force in their final report, ruled the crash a suicide/homicide by deliberate action of the captain.[19]

Legacy

Hicks' unarguably beautiful personage had once adorned magazine covers, ads, and designer clothes, yet any importance she held as a Singaporean model has largely dimmed in light of her literary contributions. Today she is most recognized for her contributions to Singaporean post-colonial literature that spoke out on subjects not normally broached, and the anthropic philosophy contained in her writings.[3] Describing the consensus of Singaporean literary scholars in 1995, two years before Hicks' death, Ismail S. Talib in The Journal of Commonwealth Literature stated of Excuse me, are you a Model?, "We have come to realize in retrospect that Hicks’s autobiographical account of her life as a model was a significant milestone in Singapore’s literary and cultural history". This recognition preceded Hicks' death, and especially in light of the controversy and even societal shunning she early faced for her writings, surely took her and many of those around her by some surprise.[1][8]

Especially among Singaporean youth, who have become increasingly uncomfortable with their country's traditional backdrops of racialism, Hicks is also recognized today as a person who learned to cross cultural boundaries, who found a comfortable niche in the betwixt and between of dominant cultural traditions, and who lived as one who was race-blind to see people for who they really were.[3]

A memorial in honor of the victims of SilkAir Flight 185 was erected beside the Musi River crash site in Indonesia. Another is at Choa Chu Kang Cemetery, Singapore.[23]

In sum, Hicks had left her mark. From one perspective, Singaporean society had itself grown up alongside her, while from another, it negatively changed as she aged and took actions upon it.[1]

External links

- Bonny Hicks Education & Training Centre. The centre was opened in Hicks' honor in 2000 by the Singapore Council of Women's Organisations. Photos available.

Also see

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Ismail S. Talib (95). "Singapore" (PDF). Journal of Commonwealth Literature 3 (35). A subscription is required to view the link.

- ↑ Divers battle muddy water at Indonesian crash site, World News, CNN. Retrieved on 2006-12-27.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 Tu Wei-Ming (1998). Celebrating Bonny Hicks' Passion for Life. Harvard University. Archived from the original on 2005-11-21. Retrieved on 2006-12-27. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "tu" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Maureen, Koh. "Mum spends birthdays at crash site", The New Paper, 2008-08-26.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Grace Chia (1998). Mermaid Princess. The Literature, Culture, and Society of Singapore. Retrieved on 2006-12-27.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Tan Gim Ean, "A Bonny way to tell the truth" New Straits Times, 30 May 1992, 28.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Cover Girl from first to last. Life Section. The Straits Times (Singapore) (28 December 1997). Retrieved on 2006-12-29. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "covgirl" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "covgirl" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "covgirl" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Rahman, Sheila, "Don't judge a covergirl by her looks," New Straits Times, 2 Sept 1990, 10.

- ↑ See http://infopedia.nl.sg/articles/SIP_1376_2010-04-29.html for an encyclopedia article on Patricia Chan Li-Yin

- ↑ Majorie Chiew (May 27, 1992). Model Bonny opts for a change in scene. The Star (Malaysia). Retrieved on 2006-12-29.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 (5 September 2001) "SilkAir". The Los Angeles Times. Dalrymple's architecture in Singapore was featured in: Dalrymple, Richard. "Pavilions for a Forest Setting in Singapore". Architectural Digest (4/91), 48 (4).

- ↑ About Flame of the Forest Publishing. Flame of the Forest Publishers (2006). Retrieved on 2006-12-27.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Poddar, Prem; Johnson, David (2005). A Historical Companion To Postcolonial Thought In English. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231135068. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "post-col2" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Hicks, Bonny (1992). Discuss Disgust. Angsana Books. ISBN 9810035063.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Eugene Benson & L.W. Conolly, eds.; Wei Li, Ng (1994). Encyclopedia of post-colonial literatures in English. London: Routledge, 656–657. ISBN 0415278856.

- ↑ Tan Gim Ean, "That's why mummy is a tart" New Straits Times, 30 May 1992, 28.

- ↑ Dalrymple's architecture in Singapore was featured in: Dalrymple, Richard. "Pavilions for a Forest Setting in Singapore". Architectural Digest (4/91), 48 (4).

- ↑ Template:ASN accident

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 "The pilot who wanted to die", Sydney Morning Herald, 10 July 1999.

- ↑ Chia, Grace (1998). Womango. Singapore: Rank Books. ISBN 9810405839.

- ↑ Ben-Shahar, Tal (1998). Heaven can Wait: Conversations with Bonny Hicks. Singapore: Times Books International. ISBN 9812049916.

- ↑ Geoff Spencer (21 December 1997). "Most passengers still strapped in their seats". Associated Press.

- ↑ Families Of SilkAir MI185 Association - Memorial Dedication Ceremony Speech. Home.pacific.net.sg. Retrieved on 2010-07-16.