User:John Stephenson/sandbox: Difference between revisions

imported>John Stephenson (Replaced content with "{{NOINDEX}}") |

imported>John Stephenson (old Xmas) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ | '''Christmas''' (literally, the [[Mass (liturgy)|Mass]] of [[Jesus|Christ]]) is a traditional [[holiday]] celebrating the birth of [[Jesus]] with both [[religious]] and [[secular]] aspects, commonly observed on [[25 December]]. In most [[Eastern Christianity|Eastern Orthodox Churches]], even where the civil calendar used is the [[Gregorian calendar|Gregorian]], the event is observed according to the [[Julian calendar]], which coincides with the predominant reckoning of [[7 January]]. Celebrated mostly by [[Christians]], the holiday is based on the traditional —though not accurate— birth of Jesus, as [[25 December]]. Recent data has concluded that Jesus was likely born earlier, circa [[8 BC]] – [[2 BC]], not to mention at a different time of year. Christ's birth, or [[nativity]], was said by his followers to fulfill the prophecies of [[Judaism]] that a [[messiah]] would come, from the house of [[David]], to redeem the world from sin. Efforts to decide upon a date on which to celebrate his birth began some centuries later. | ||

The word ''Christmas'' is a contraction of ''Christ's Mass'', derived from the [[Old English]] ''Cristes mæsse''. It is often abbreviated ''[[Xmas]]'', probably because ''X'' resembles the [[Greek language|Greek]] letter [[Chi (letter)|Χ]] (chi) which has often historically been used as an abbreviation for Christ (Χριστός in Greek). | |||

Christmas has acquired many secular aspects, which are sometimes celebrated as often—or more—than the birth of Jesus. Many Christmas traditions originated with pre-Christian observances that were [[Syncretism|syncretised]] into Christianity. Examples of this process are the northern European [[Yule]], and the [[Winter Solstice]] celebration found in many older as well as recent pagan celebrations. | |||

In Western countries, Christmas has become the most economically significant holiday of the year. It is largely characterized by gifts being exchanged between friends and family members, and the appearance of [[Santa Claus]]. Various local and regional Christmas traditions are still practised, despite the widespread influence of [[United States|American]], [[United Kingdom|British]] and [[Australia|Australian]] Christmas motifs disseminated by [[globalization]], popular literature, television, and other media. | |||

==The Nativity== | |||

[[Image:Adorazione del Bambino - Beato Angelico.jpg|thumb|right|''Adorazione del Bambino'' (Adoration of the Child) by [[Beato Angelico]].]] | |||

The story of Christ's birth has been handed down for centuries, based mainly on the Christian [[gospels]] of [[Gospel of Matthew|Matthew]] and [[Gospel of Luke|Luke]]. The gospels of [[Gospel of Mark|Mark]] and [[Gospel of John|John]] do not address the childhood of Jesus, and those of Matthew and Luke highlight different events. | |||

According to Luke, Mary learns from an [[angel]] that the [[Holy Spirit]] has caused her to be with child. Shortly thereafter, she and her husband [[Saint Joseph|Joseph]] leave their home in [[Nazareth]] to travel about 150 kilometres (90 miles) to Joseph's ancestral home, [[Bethlehem]], to enroll in the [[census]] ordered by the Roman emperor, [[Augustus]]. Finding no room in inns in the town, they set up lodgings in a stable in Bethlehem in [[Judea]]. There Mary gives birth to Jesus. Jesus' being born in Bethlehem fulfills the prophecy of the [[Book of Micah]]. [[Gospel of Luke|Luke's Gospel]] has some references to historic events at this time, saying "In these days the Roman emperor [[Augustus]] ordered to excise a counting of all population in the world" (Lk 2,1), but the only known census was in the year [[Anno Domini|AD]] [[6]]. | |||

Matthew's gospel begins by telling the [[genealogy]] and birth of Jesus, and then moves to the coming of [[Biblical Magi|the Magi]] (sometimes erroneously translated simply as ''wise men'' - some translations add the number ''three'', although the number is not actually specified) from the East to Bethlehem. Matthew mentions no trek to Bethlehem from Nazareth. The Magi first arrive in Jerusalem and report to the king of [[Judea]], [[Herod the Great]], that they have seen a star, now called the [[Star of Bethlehem]], heralding the birth of a king. Further inquiry leads them to Bethlehem of Judea and the home of Mary and Joseph. They present Jesus with treasures of "[[gold]], [[frankincense]], and [[myrrh]]". While staying the night, [[Biblical Magi|the Magi]] have a dream that contains a divine warning that King Herod has [[murder]]ous designs on the child. Resolving to hinder the ruler, they go home without telling Herod of the success of their mission. Matthew then reports that the family next flees to [[Egypt]] to escape the murderous rampage of Herod, who has decided to have all children of Bethlehem under the age of two killed in order to eliminate any local rivals to his power. After Herod's death, Jesus and his family return from Egypt, but fearing the hostility of the new Judean king (Herod's son [[Herod Archelaus|Archelaus]]) they go instead to Galilee and settle in Nazareth. | |||

Another aspect of Christ's birth which has passed from the gospels into popular lore is the announcement by [[angel]]s to nearby [[shepherd]]s of Jesus's birth. Some Christmas [[carol]]s refer to the shepherds observing a bright star directly over Bethlehem, and following it to the birthplace. The Magi, who Matthew also reports seeing a giant star, have been variously interpreted as wise men or as kings. They are supposed to have come from [[Arabia]] or [[Persia]], where they might have obtained their particular gifts. Through the years [[astronomy|astronomers]] and [[historian]]s have offered conflicting explanations of what combination of traceable [[celestial]] events might explain the appearance of a giant star that had never before been seen.<ref>{{cite journal | author=David van Biema | title=Behind the First Noel | journal=[[Time (magazine)|Time magazine]] | year=13 December 2004 | volume=20 | pages=49-61}}</ref> | |||

==Theories on the origins of Christmas== | |||

Many different dates have been suggested for the celebration of Christmas. The theories for the reason Christmas is celebrated on [[December 25]] are many and varied; none are universally accepted. | |||

The Romans marked the [[winter solstice]] or ''bruma'' on December 25, although on the Roman calendar the date of the astronomical solstice varies between [[December 21]] (the modern date) and December 24. Various cultures believed that their [[sun god]] was reborn on the solstice, the shortest day of the year. | |||

It is alleged that, according to [[Celtic Mythology]], the sun god was crucified on the winter solstice, and three days later, as the days grew longer again, he rose from the dead. It is said that this was the origin of the [[Celtic cross]], symbolising the crucified sun god, thus making it a few thousand years older than Christianity. Nevertheless, there is no record of the Celts actually ever practicing crucifixion or stories of any crucifixion of a "Celtic Sun God" before 19th century source. Crosses and circles are found worldwide as solar symbol, whether or not a particular culture practiced crucifixion. | |||

Christianity, and thus Christmas, formed during the Roman Empire. The [[Ancient Rome|Romans]] honored [[Saturn (mythology)|Saturn]], the ancient god of agriculture, each year on [[December 17]]. In a festival called [[Saturnalia]], they glorified the "golden age" when the god Saturn ruled. This festival was eventually extended to six days. During Saturnalia the Romans feasted, postponed all business and warfare, exchanged gifts, and temporarily freed their slaves. Such traditions resemble those of Christmas and are used to establish a link between the two holidays. These and other winter festivities continued through [[January 1]], the festival of [[Kalends]], when Romans marked the day of the [[new moon]] and the first day of the month as well as the beginning of the religious year. | |||

According to the ''[[Catholic Encyclopedia]]'', Christmas is not included in Irenaeus's nor Tertullian's list of Christian feasts, the earliest known lists of Christian feasts. The earliest evidence of celebration is from [[Alexandria]], in about 200, when [[Clement of Alexandria]] says that certain [[Egypt]]ian theologians "over curiously" assign not just the year but also the actual day of Christ's birth as 25 Pachon ([[May 20]]) in the twenty-eighth year of Augustus.<ref>{{cite book | title=Stromateis'', I, xxi | publisher=Patrologia Graeca | year=VIII, 888}}</ref> By the time of the [[First Council of Nicaea|Council of Nicaea]] in 325, the Alexandrian church had fixed a ''dies Nativitatis et Epiphaniae''. The December feast reached Egypt in the fifth century. In Jerusalem, the fourth century [[pilgrim]] [[Egeria (nun)|Egeria]] from [[Bordeaux]] witnessed the Feast of the Presentation, forty days after [[January 6]], which must have been the date of the Nativity there. At [[Antioch]], probably in 386, St. [[John Chrysostom]] urged the community to unite in celebrating Christ's birth on [[December 25]], a part of the community having already kept it on that day for at least ten years. | |||

In the late [[Roman Empire]], the festival of Sol Invictus was celebrated [[December 25]]. In 350, [[Pope Julius I]] ordered that the birth of Christ be celebrated on the same date. | |||

Some scholars maintain that [[December 25]] was only adopted in the 4th century as a Christian holiday after [[Constantine I (emperor)|Roman Emperor Constantine]] converted to Christianity to encourage a common religious festival for both Christians and [[Paganism|pagans]]. Perusal of historical records indicates that the first mention of such a feast in Constantinople was not until 379, under [[Gregory Nazianzus]]. In Rome, it can only be confirmed as being mentioned in a document from approximately 350 but without any mention of sanction by Emperor Constantine. | |||

An alternative theory asserts that the date of Christmas is based on the date of [[Good Friday]], the day Jesus died. Since the exact date of Jesus' death is not stated in the Gospels, early Christians sought to calculate it, and arrived at either [[March 25]] or [[April 6]]. To then calculate the date of Jesus' birth, they followed the ancient idea that Old Testament prophets died at an "integral age" — either an anniversary of their birth or of their conception. They reasoned that Jesus died on an anniversary of the Incarnation (his conception), so the date of his birth would have been nine months after the date of Good Friday — either [[December 25]] or [[January 6]]. Thus, rather than the date of Christmas being appropriated from pagans by Christians, the opposite is held to have occurred.<ref>{{cite book | first=Louis | last=Duchesne | year=1889 | title=Les origines du culte chrétien: Etude sur la liturgie latine avant Charlemagne | language=French, translated to English 1903 | location=Paris }}(see [[Louis Duchesne]])</ref><ref>{{cite book | first=Thomas J | last=Talley | year=1986 | title=The Origins of the Liturgical Year | publisher=Pueblo Publishing Company | location=New York }}</ref> | |||

Another extremely popular cult of Persian origin, in those days was that of [[mitra|Mithras]]. The similarities between Jesus and Mithras are many. Mithras was born on [[December 25]] of virgin birth, the son of the primary Persian deity, Ahura-Mazda. His birth was witnessed by shepherds and magi. He was reputed to have raised the dead, healed the sick and cast out demons. He had a Lord's Supper. His day of worship was Sunday. He was killed and resurrected, returned to heaven on the spring equinox after a last meal with his 12 disciples (representing the signs of the zodiac), eating "mizd" - a piece of bread marked with a cross (an almost universal symbol of the sun). The Mithraic cult peaked around the year 300 AD when it became the official religion of the empire. At that time, in every town and city, in every military garrison and outpost from Syria to the Scottish frontier, was to be found a Mithraeum and officiating priests of the cult. This is not to suggest that the Mithraic cult was the only factor in this syncretization, many pagan gods had similar aspects of mythology (e.g. resurrection, virgin mother etc). | |||

Early Christians chiefly celebrated the [[Epiphany (feast)|Epiphany]], when the baby Jesus was visited by the [[Magi]] (and this is still a primary time for celebration in [[Argentina]], [[Spain]] and [[Armenia]]). Historians are unsure exactly when Christians first began celebrating the [[Nativity of Christ]]. At times it was forbidden by [[Protestant]] churches until after the 1800s because of its association with Catholicism. | |||

Some Christmas traditions, particularly those in [[Scandinavia]], have their origin in the Germanic [[Yule]] celebration. Christmas is still known as ''Yule'' (or: Jul) in Scandinavian countries. | |||

===When was the original Christmas?=== | |||

{{seealso|Chronology of Jesus}} | |||

Early Christians sought to calculate the date of Christ's birth based on the idea that [[Old Testament]] [[prophet]]s died either on an anniversary of their birth or of their conception. They reasoned that Jesus died on an anniversary of his conception, so the date of his birth was nine months after the date of Good Friday, either [[December 25]] or [[January 6]]. <!--The celebration of solstice is much older than 2,000 years; it certainly wasn't taken from the Christians.--> | |||

[[Hippolytus (writer)|St. Hippolytus]], who was already knowledgeably defending the faith in writing at the start of the third century, said that Christ was born Wednesday, [[December 25]], in the 42nd year of [[Augustus]]' reign (see his ''Commentary on Daniel'', circa 204, Bk. 4, Ch. 23). | |||

Additional calculations are made based on the six-year [[almanac]] of [[priest]]ly [[Job rotation|rotations]], found among the [[Dead Sea Scrolls]]. Some believe that this almanac lists the week when [[John the Baptist]]'s father served as a [[high priest]]. As it is implied that John the Baptist could only have been conceived during that particular week, and as his conception is believed to be tied to that of Jesus, it is claimed that an approximate date of [[December 25]] can be arrived at for the birth of Jesus. However, most scholars (e.g. ''[[Catholic Encyclopedia]]'' in sources) believe this calculation to be unreliable as it is based on a string of assumptions. | |||

The apparition of the angel [[Gabriel]] to [[Zacharias|Zechariah]], announcing that he was to be the father of [[John the Baptist]], was believed to have occurred on [[Yom Kippur]]. This was due to a belief (not included in the [[Gospel]] account) that Zechariah was a high priest and that his vision occurred during the high priest's annual entry into the [[Holy of Holies]]. If John's conception occurred on Yom Kippur in late September, then his birth would have been in late June. If John's birth was on the date ascribed by tradition, [[June 24]], then the [[Annunciation]] to the [[Blessed Virgin Mary]], said by the Gospel account to have occurred three month's before John's birth, would have been in late March. (Tradition fixed it on [[March 25]].) The birth of Jesus would then have been on [[December 25]], nine months after his conception. As with the previous theory, proponents of this theory hold that Christmas was a date of significance to Christians before it was a date of significance to pagans. | |||

==Dates of celebration== | |||

[[Image:Christmas.house.arp.750pix.jpg|thumbnail|250px|right|A house decorated for Christmas in Yate, England]] | |||

Efforts to fix a date for the birth of Christ began some two centuries after his death, as the [[Catholic Church]] began to establish its traditions. Christmas is now celebrated on [[December 25]] in Catholic and Catholic-derived churches ([[Roman Catholic|Roman]] and [[Protestant]]), and thus in most of the Western world. In the nations of the former [[Soviet Union]], the [[Balkans]], and other regions where the [[Eastern Orthodoxy|Eastern Rite]] churches are more prominent, Christmas is now celebrated on [[January 7]]. This date results from their having accepted neither the reforms of the [[Gregorian calendar]] nor the [[Revised Julian calendar]], with their ecclesiastic [[December 25]] thus falling on the civil date of [[January 7]] from [[1900]] to [[2099]]. The [[Armenian Church]] places much more emphasis on the [[Epiphany]], the visitation by the Magi, than on Christmas. This calendrical difference has led to confusion on the part of those unfamiliar with the older calendar. | |||

The Orthodox churches begin preparing for Christmas with a fast that begins 40 days before Christmas and ends with Christmas, dubbed the "Feast of the Nativity of our Lord, God, and Saviour Jesus Christ." In the U.S. and Canada, some Orthodox dioceses allow the parish priest or parish to decide which of the two calendars (i.e., Gregorian versus old Julian) to follow at the parish level and hence the timing of Christmas Day. Armenian Christians celebrate Christmas on [[January 6]]th except those in Jerusalem, who still use the old calendar and celebrate Christmas on [[January 18]].<ref>{{cite web | author=Tchilingirian, Hratch| title=ARMENIAN CHRISTMAS | work=Why Armenians Celebrate Christmas on January 6th?| url=http://www.sain.org/Armenian.Church/xmas.txt| accessdate=2006-04-14}}</ref> | |||

Dates for the more secular aspects of the Christmas celebration are similarly varied. In the [[United Kingdom]], the [[Christmas season]] traditionally runs for twelve days beginning on [[Christmas Day]]. These [[twelve days of Christmas]], a period of feasting and merrymaking, end on [[Twelfth Night (holiday)|Twelfth Night]], the eve of the Feast of the [[Epiphany (feast)|Epiphany]]. This period corresponds with the [[liturgy|liturgical season]] of Christmas. [[Medieval]] laws in [[Sweden]] declared a Christmas peace (''julefrid'') to be twenty days, during which fines for [[robbery]] and [[manslaughter]] were doubled. Swedish children still celebrate a party, throwing out the [[Christmas tree]] (''julgransplundring''), on the 20th day of Christmas ([[January 13]], [[Knut]]'s Day). | |||

In practice, the Christmas festive period has grown longer in some countries, including the [[United States]] and the United Kingdom, and now begins many weeks before Christmas, allowing more time for shopping and get-togethers. It often extends beyond Christmas Day up to [[New Year's Day]], this later holiday having its own parties. In the [[Philippines]], radio stations usually start playing Christmas music during what is called the "-ber months" (September, October, etc.); this usually marks the start of the Christmas season. | |||

Countries that celebrate Christmas on [[December 25]] recognize the previous day as [[Christmas Eve]], and vary on the naming of [[December 26]]. In the [[Netherlands]], [[Germany]], [[Scandinavia]], [[Lithuania]] and [[Poland]], Christmas Day and the following day are called First and Second Christmas Day. In many [[Europe]]an and [[Commonwealth of Nations|Commonwealth]] countries, [[December 26]] is referred to as [[Boxing Day]], while in [[Finland]], [[Ireland]], [[Italy]], [[Romania]], [[Austria]] and [[Catalonia]] ([[Spain]]) it is known as [[St. Stephen's Day]]. In [[Canadian French]], the [[December 26]] holiday is generally referred to as ''Lendemain de Noël'' (which literally means "the day after Christmas"). | |||

==Regional customs and celebrations== | |||

{{main|Christmas worldwide}} | |||

[[Image:wiki_christmas.JPG|thumb|left|Many postal services release [[Postage stamp|stamps]] each year to commemorate Christmas. This one is from [[Austria]] and was produced in 1999]] | |||

A plethora of customs with secular, religious, or national aspects surround Christmas, varying from country to country. Most of the familiar traditional practices and symbols of Christmas originated in Germanic countries, including the now omnipresent [[Christmas tree]], the [[Christmas ham]], the [[Yule Log]], [[holly]], [[mistletoe]], and the giving of [[presents]] to friends and relatives. These practices and symbols were adapted or appropriated by Christian [[missionaries]] from the earlier [[Germanic paganism|Germanic pagan]] midwinter holiday of [[Yule]]. This celebration of the [[winter solstice]] was widespread and popular in northern Europe long before the arrival of Christianity, and the word for Christmas in the Scandinavian languages is still today the pagan ''jul'' (=yule). | |||

Rather than attempting to suppress every pagan tradition, [[Pope]] [[Gregory I]] allowed Christian missionaries to synthesize them with Christianity, allowing many pagan traditions to become a part of Christmas.<ref>The [[8th-century]] [[England|English]] historian [[Bede]]'s ''[[Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum]]'' (''Ecclesiastic History of the English People'') contains a letter from [[Pope]] [[Gregory I]] to [[Saint Mellitus]], who was then on his way to England to conduct missionary work among the [[heathen]] [[Anglo-Saxons]]. The Pope suggests that converting heathens is easier if they are allowed to retain the outward forms of their traditional pagan practices and traditions, while recasting those traditions spiritually towards the one true God instead of to their pagan gods (whom the Pope refers to as "devils"). "[T]o the end that, whilst some gratifications are outwardly permitted them, they may the more easily consent to the inward consolations of the [[divine grace|grace of God]]." The Pope sanctions such conversion tactics as Biblically acceptable, pointing out that God did much the same thing with the ancient [[Israelite]]s and their pagan sacrifices, although he never spoke of Christmas as a mere concession.[http://www.englishheathenism.homestead.com/popesletter.html]</ref> | |||

The dynamic relationship between religious and governmental authorities and celebrators of Christmas continued through the years. Places where conservative Christian [[theocracy|theocracies]] flourished, as in [[Oliver Cromwell|Cromwellian England]] and in the early [[New England]] [[Thirteen Colonies|colonies]], were among those where celebrations were suppressed.<ref>After [[Oliver Cromwell]]'s Puritans took over England in 1645, the observance of Christmas was prohibited in 1652 as part of a Puritan effort to rid the country of decadence. This proved unpopular, and when [[Charles II of England|Charles II]] was restored to the throne, he restored the celebration. The [[Pilgrims]], a group of Puritanical English separatists who came to North America in 1620, also disapproved of Christmas. As a result it was not a holiday in [[New England]]. The celebration of Christmas was actually outlawed from 1659 to 1681 in [[Boston, Massachusetts|Boston]], a prohibition enforced with a fine of five [[shilling]]s. The English of the [[Jamestown, Virginia|Jamestown]] settlement and the Dutch of [[New Amsterdam]], on the other hand, celebrated the occasion freely. Christmas fell out of favor again after the [[American Revolution]], as it was considered an "English custom". Interest was revived by [[Washington Irving]]'s Christmas stories, German immigrants, and the homecomings of the [[American Civil War|Civil War]] years. [[December 25]] was declared a federal holiday in the United States on [[June 26]], [[1870]].</ref> | |||

After the [[Russian Revolution of 1917|Russian Revolution]], Christmas celebrations were banned in the [[Soviet Union]] for the next seventy-five years. | |||

Several Christian denominations, notably the [[Jehovah's Witnesses]], some [[Puritan]] groups, and some [[fundamentalist Christian]]s, view Christmas as a pagan holiday not sanctioned by the [[Bible]] and refuse to celebrate or recognize it in any way. Incidentally, this was the practice of the Puritans in 17th and 18th Century England and the American Colonies. Christmas was not widely celebrated in New England until after the middle of the [[19th Century]]. | |||

In [[Commonwealth]] countries in the [[southern hemisphere]], Christmas is still celebrated on [[25 December]], despite this being the height of their summer season. This clashes with the traditional winter iconography, resulting in anachronisms such as a red fur-coated Santa Claus surfing in for a turkey barbecue on [[Australia]]'s [[Bondi Beach]]. [[Japan]] has largely adopted the western Santa Claus for its secular Christmas celebration, but their [[New Year's Day]] is considered the more important holiday. Christmas is also known as ''bada din'' (the big day) in [[Hindi]], and revolves there around Santa Claus and shopping. In [[South Korea]], Christmas is celebrated as an official holiday. | |||

===Religious customs and celebrations=== | |||

The religious celebrations begin with [[Advent]], the anticipation of Christ's birth, around the start of December. (In most western churches, Advent starts the 4th Sunday before Christmas Day, and thus can last for 21 to 28 days.) These observations may include Advent carols and Advent calendars, sometimes containing sweets and chocolate for children. Christmas Eve and Christmas Day services may include a [[midnight mass]] or a [[Mass (liturgy)|Mass]] of the [[Nativity]], and feature [[Christmas carol]]s and hymns. | |||

===Secular customs=== | |||

Christmas customs and traditions transmitted through mass culture have been adopted by Christians and non-Christians alike, particularly in North America. | |||

[[Image:DSC04820.JPG|thumb|250px|right|A Christmas display in a Brazilian shopping mall]] | |||

Since the customs of Christmas celebration largely evolved in [[northern Europe]], many are associated with the [[Northern Hemisphere]] winter, the motifs of which are prominent in Christmas decorations and in [[Santa Claus]] stories. | |||

===Santa Claus and other bringers of gifts=== | |||

Gift-giving is a near-universal part of Christmas celebrations. The concept of a mythical figure who brings gifts to children derives from [[Saint Nicholas]], a [[bishop]] of [[Myra]] in [[fourth century]] Lycia, [[Asia Minor]]. He made a pilgrimage to Egypt and Palestine in his youth and soon thereafter became Bishop of Myra. He was imprisoned during the persecution of Diocletian and released after the accession of Constantine. He may have been present at the Council of Nicaea, though there is no record of his attendance. He died on [[December 6]] of 345 or 352. In 1087, Italian merchants stole his deceased body at Myra and brought it to Bari in Italy. His relics are still preserved in the church of San Nicola in Bari. To this day, an oily substance known as Manna di S. Nicola, which is highly valued for its medicinal powers, is said to flow from his relics <ref>{{cite web | year=1998| title=St. Nicholas of Myra | work=Catholic Encyclopedia | url=http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11063b.htm | accessdate=2006-04-14}}</ref>. | |||

The [[the Netherlands|Dutch]] modeled a gift-giving [[Saint Nicholas]] on the eve of his feast day on [[December 6]]. In [[North America]], other colonists adopted the feast of [[Sinterklaas]] brought by the Dutch into their Christmas holiday, and Sinterklaas became [[Santa Claus]], or ''Saint Nick'', known in some West African and the UK countries as [[Father Christmas]]. In the Anglo-American tradition, this jovial fellow arrives on Christmas Eve on a [[sleigh]] pulled by [[reindeer]], and lands on the roofs of houses. He then climbs down the [[chimney]], leaves gifts for the children, and eats the food they leave for him. He spends the rest of the year making toys and keeping lists on the behaviour of the children. | |||

One belief in the United Kingdom, United States, and other countries passed down through the generations is the idea of lists of good children and bad children. Throughout the year, Santa supposedly adds names of children to either the good or bad list depending on their behaviour. When it gets closer to Christmas time, parents use the belief to encourage children to behave well. Those who are on the bad list and whose behaviour has not improved before Christmas are said to receive a [[booby prize]], such as a piece of coal or a [[Switch (rod)|switch]] with which their parents beat them, rather than presents. | |||

The [[French language|French]] equivalent of Santa, [[Père Noël]], evolved along similar lines, eventually adopting the Santa image [[Haddon Sundblom]] painted for a worldwide [[Coca-Cola]] advertising campaign in the 1930s. In some cultures Santa Claus is accompanied by [[Knecht Ruprecht]], or [[Black Peter]]. In some versions, [[elf|elves]] in a toy workshop make the holiday toys, and in some he is married to [[Mrs. Claus]]. Many [[shopping mall]]s in [[North America]], the United Kingdom, and [[Australia]] have a holiday mall Santa Claus whom children can visit to ask for presents. | |||

[[Image:Jolly-old-saint-nick.gif|left|framed|A classic image of Saint Nick]] | |||

In many countries, children leave empty containers for Santa to fill with small gifts such as toys, candy, or fruit. In the United Kingdom, the United States, and [[Canada]] children hang a [[Christmas stocking]] by the fireplace on Christmas Eve because Santa is said to come down the chimney the night before Christmas to fill them. In other countries, children place their empty shoes out for Santa to fill on the night before Christmas, or for Saint Nicholas to fill on [[December 5]] before his feast day the next day. Gift giving is not restricted to these special gift-bringers, as family members and friends also bestow gifts on each other. | |||

====Timing of gifts==== | |||

In many countries, [[Saint Nicholas]]'s Day remains the principal day for gift giving. In such places, including the [[Netherlands]], Christmas Day remains more a religious holiday. In much of [[Germany]], children put shoes out on window sills on the night of [[December 5]], and find them filled with [[candy]] and small gifts the next morning. The main day for gift giving, however, is [[December 24]], when gifts are brought by Santa Claus or are placed under the Christmas tree. Same in [[Hungary]], except that the Christmas gifts are usually brought by Jesus, not by Santa Claus. In other countries, including [[Spain]], gifts are brought by the [[Magi]] at [[Epiphany]] on [[January 6]]. In [[Poland]], Santa Claus ([[Polish language|Polish]]: Święty Mikołaj) gives gifts at two occasions: on the night of [[December 5]] (so that children find them on the morning of [[December 6]]) and on [[Christmas Eve]], [[December 24]], (so that children find gifts that same day). In [[Finland]] ''[[Joulupukki]]'' personally meets children and gives gifts on [[December 24]]. In [[Russia]], ''[[Grandfather Frost]]'' brings presents on New Year's Eve, and these are opened on the same night. | |||

One of the many customs of gift timing is suggested by the song "[[Twelve Days of Christmas]]", celebrating an old British tradition of gifts each day from Christmas to Epiphany. In most of the world, Christmas gifts are given at night on Christmas Eve or in the morning on Christmas Day. Until recently, gifts were given in the UK to non-family members on [[Boxing Day]]. | |||

===Declaration of Christmas Peace=== | |||

Declaration of Christmas Peace has been a tradition in [[Finland]] from the Middle Ages every year, except in 1939 due to the war. The declaration takes place on the Old Great Square of [[Turku]], Finland's official Christmas City and former capital, at noon on Christmas Eve. It is broadcast in Finnish radio (since 1935) and television and nowadays also in some foreign countries. | |||

The declaration ceremony begins with the hymn ''Jumala ompi linnamme'' ([[Martin Luther]]'s ''Ein` feste Burg ist unser Gott'') and continues with the Declaration of Christmas Peace read from a parchment roll: | |||

"Tomorrow, God willing, is the graceful celebration of the birth of our Lord and Saviour; and thus is declared a peaceful Christmas time to all, by advising devotion and to behave otherwise quietly and peacefully, because he who breaks this peace and violates the peace of Christmas by any illegal or improper behaviour shall under aggravating circumstances be guilty and punished according to what the law and statutes prescribe for each and every offence separately. Finally, a joyous Christmas feast is wished to all inhabitants of the city." | |||

Recently there have also been declarations of Christmas peace for forest animals in many cities and municipalities, restricting hunting during the holiday. | |||

===Christmas cards=== | |||

[[Image:Julekort.jpg|thumb|left|A large variety of commercial Christmas cards are available in stores across the world.]] | |||

[[Christmas card]]s are extremely popular in [[New Zealand]], [[Australia]], [[Canada]], the [[United States]], and [[Europe]], in part as a way to maintain relationships with distant relatives, friends, and business acquaintances. Many families enclose an annual family photograph or a family newsletter summarizing the adventures and accomplishments of family members during the preceding year. | |||

===Decorations=== | |||

[[Image:Brazilian-christmas-tree.jpg|thumb|Christmas tree in a Brazilian home.]] | |||

Decorating a Christmas tree with [[Christmas lights|lights]] and [[Christmas ornaments|ornaments]] and the decoration of the interior of the home with [[garland]]s and [[evergreen]] foliage, particularly [[holly]] and [[mistletoe]], are common traditions. In [[Australia]], [[North America|North]] and [[South America]] and to a lesser extent [[Europe]], it is traditional to decorate the outside of houses with lights and sometimes with illuminated sleighs, snowmen, and other Christmas figures. | |||

Since the 19th century, the traditional Christmas flower has been the winter-blooming [[poinsettia]]. Other popular holiday plants include [[holly]], [[mistletoe]], red [[amaryllis]], and [[Christmas cactus]]. | |||

Municipalities often sponsor decorations as well, hanging Christmas banners from street lights or placing Christmas trees in the town square. In the US, decorations once commonly included religious themes. This practice has led to much adjudication, as some say it amounts to the government endorsing a religion. In 1984 the [[Supreme Court of the United States|US Supreme Court]] ruled that a city-owned Christmas display including a Christian [[nativity]] scene was depicting the historical origins of Christmas and was not in violation of the [[First Amendment to the United States Constitution|First Amendment]] <ref>{{cite web | title=Lynch v. Donnelly | url=http://www.belcherfoundation.org/lynch_v_donnelly.htm | |||

|year=1984}}</ref>. | |||

Although Christmas decorations, such as the tree, are essentially [[secular]] in character in some parts of the world, e.g. in the [[Saudi Arabia|Kingdom of Saudi Arabia]], such display is banned on the grounds that the symbols are of [[Christianity]] (which is proscribed). | |||

===Social aspects and entertainment=== | |||

[[Image:CandyCane.JPG|left|thumb|[[Candy cane]]s are a popular Christmas treat, and may double as a decoration or Christmas ornament.]] | |||

In many countries, businesses, schools, and communities have Christmas parties and dances during the several weeks before Christmas Day. Christmas [[pageant]]s, common in [[Latin America]], may include a retelling of the story of the birth of Christ. Groups may go [[Christmas carols|caroling]], visiting neighborhood homes to sing Christmas songs. Others are reminded by the holiday of their kinship with the rest of humanity and do [[volunteer]] work or hold [[fundraising]] drives for [[charities]]. | |||

<!--[[Image:Now is it Christmas again (1907) by Carl Larsson.jpg|thumbnail|300px|"Now it is Christmas again" by Carl Larsson.]]--> | |||

On Christmas Day or Christmas Eve, a special meal of [[Christmas dishes]] is usually served, for which there are different traditional menus in many country. In some regions, particularly in [[Eastern Europe]], these family feasts are preceded by a period of [[fasting]]. Candy and treats are also part of the Christmas celebration in many countries. | |||

Because of the focus on celebration, friends, and family, people who are without these, or who have recently suffered losses, are more likely to suffer from depression during Christmas. This increases the demands for counseling services during the period. | |||

It is widely believed that suicides and murders spike during the holiday season. However, the peak months for suicide are May and June. Because of holiday celebrations involving alcohol, drunk driving-related fatalities may also increase. | |||

Non-Christians in predominantly Christian nations may have few choices for entertainment around Christmas, as stores close and friends depart for vacations. The cliché recreation for them is "movies and Chinese food"; movie theaters remaining open to bring in holiday box office dollars and Chinese (and presumably Buddhist, et al.) establishments being less likely to close for the "big day". | |||

===Christmas carol media=== | |||

{{multi-listen start}} | |||

{{multi-listen item|filename=Deck the Halls.ogg|title=Deck the Halls|description=[[Deck the Halls]]|format=[[Ogg]]}} | |||

{{multi-listen item|filename=Oh holy night.ogg|title=Oh Holy Night|description=[[Oh Holy Night]]|format=[[Ogg]]}} | |||

{{multi-listen item|filename=Angels We Have Heard On High.ogg|title=Angels We Have Heard On High|description=[[Angels We Have Heard On High]], performed by Clarinet and French Horn|format=[[Ogg]]}} | |||

{{multi-listen end}} | |||

==Christmas in the arts and media== | |||

{{main|Christmas in the media}} | |||

Many fictional Christmas stories capture the spirit of Christmas in a modern-day [[fairy tale]], often with heart-touching stories of a Christmas [[miracle]]. Several have become part of the Christmas tradition in their countries of origin. | |||

Among the most popular are [[Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky|Tchaikovsky's]] ballet ''[[The Nutcracker]]'' and Charles Dickens's novel ''[[A Christmas Carol]]''. ''[[The Nutcracker]]'' tells of a [[nutcracker]] that comes to life in a young [[Germany|German]] [[girl|girl's]] dream. [[Charles Dickens]]' ''[[A Christmas Carol]]'' is the tale of curmudgeonly miser [[Ebenezer Scrooge]]. Scrooge rejects [[compassion]] and [[philanthropy]], and Christmas as a symbol of both, until he is visited by the ghosts of Christmas Past, Present and Future, who show him the consequences of his ways. Dickens is sometimes credited with shaping the modern Christmas of English-speaking countries of Christmas trees, [[plum pudding]], and Christmas carols with shaping the movement to close businesses on Christmas Day. | |||

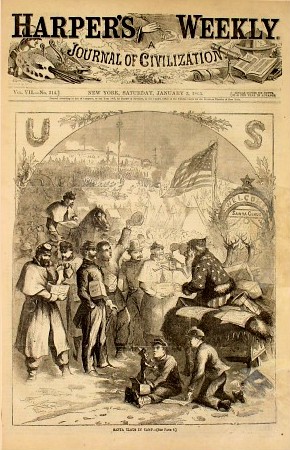

[[Image:1863 harpers.jpg|thumb|left|Thomas Nast helped standardize the modern image of Santa Claus, as seen in this cartoon he produced for an 1863 edition of ''[[Harper's Weekly]]''.]] | |||

Just as Dickens shaped Christmas traditions, 19th century cartoonist [[Thomas Nast]] gave Santa his familiar form (''[[Harper's Weekly]]'', 1863). "[[A Visit from St. Nicholas]]" (''Sentinel'', 1823, authorship by either [[Henry Livingston Jr.]] or [[Clement Clarke Moore]] and popularly known as "The Night Before Christmas") supplied the rotund Santa and his sleigh landing on rooftops on Christmas Eve. | |||

In 1881, the [[Sweden|Swedish]] [[magazine]] ''Ny Illustrerad Tidning'' published [[Viktor Rydberg]]'s poem ''Tomten'' featuring the first painting by [[Jenny Nyström]] of the traditional Swedish mythical character ''[[tomte]]'' which she turned into the friendly white-bearded figure associated with Christmas. Her figure was further developed in 1931 by [[Haddon Sundblom]] for the [[Coca-Cola Company]]. | |||

Although Christmas [[icon]]s have become widespread through television and movies, Christmas is still a time when national traditions are strong, and both Santa's appearance and the stories told vary from country to country. Some Scandinavian Christmas stories are less cheery than Dickens's, notably [[Hans Christian Andersen|H. C. Andersen's]] ''[[The Little Match Girl]]''. A destitute little [[slum]] girl walks barefoot through snow-covered streets on Christmas Eve, trying in vain to sell her matches, and peeking in at the celebrations in the homes of the more fortunate. She dares not go home because her father is drunk. Unlike the principals of Anglophone Christmas lore, she meets a tragic end. | |||

[[Image:Dvd-cover-white-christmas.jpg|thumb|Unlike many films, which date rapidly, Christmas movies are the reliable annuals of the movie business.]] | |||

Many Christmas stories have been popularized as [[film|movies]] and [[TV special]]s. Since the 1980s, many video editions are sold and resold every year during the holiday season. A notable example is the film ''[[It's a Wonderful Life]]'', which turns the theme of ''A Christmas Carol'' on its head. Its hero, [[George Bailey]], is a businessman who sacrificed his dreams to help his community. On [[Christmas Eve]], a [[guardian angel]] finds him in despair and prevents him from committing [[suicide]], by magically showing him how much he meant to the world around him. Perhaps the most famous animated production is ''[[A Charlie Brown Christmas]]'' wherein [[Charlie Brown]] tries to address his feeling of dissatisfaction with the holidays by trying to find a deeper meaning to them. The humorous ''[[A Christmas Story]]'' (1983) has become a holiday classic and is shown for 24 hours straight from Christmas Eve to Christmas Day on [[TNT]]/[[TBS (TV network)|TBS]]. | |||

A few true stories have also become enduring Christmas tales themselves. The story behind the Christmas carol ''[[Silent Night]]'' and the story ''[[Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus]]'' is among the most well-known of these. | |||

[[Radio]] and [[television]] programs have also aggressively pursued entertainment and ratings through their cultivation of Christmas themes. Radio stations broadcast [[Christmas carol]]s and [[Christmas song]]s, including [[European classical music|classical music]] such as the [[Hallelujah chorus]] from [[Handel]]'s ''[[Messiah (Handel)|Messiah]]''. Among other classical pieces inspired by Christmas are the ''[[Nutcracker Suite]]'', adapted from Tchaikovsky's ballet score, and [[Johann Sebastian Bach]]'s ''Christmas Oratorio'' ([[BWV]] 248). Television networks add Christmas themes to their standard programming, run traditional holiday movies, and produce a variety of Christmas specials. | |||

==Economics of Christmas== | |||

Christmas is typically the largest annual stimulus for the economies of celebrating nations. Sales increase dramatically in almost all retail areas and shops introduce new products as people purchase gifts, decorations, and supplies. In the US, the Christmas shopping season now begins on [[Black Friday (shopping)|Black Friday]], the day after [[Thanksgiving]]. The economic impact of Christmas continues after the holiday, with Christmas sales and New Year's sales, when stores sell off excess inventories. | |||

More businesses and stores close on Christmas Day than any other day of the year in most countries - in most communities, virtually nothing is open or operating. In the [[United Kingdom]], the [[Christmas Day (Trading) Act 2004]] prevents all large shops from trading on Christmas Day. | |||

Many religious [[Christians]], as well as anti-[[consumerism|consumerists]], decry the commercialization of Christmas. They accuse the Christmas season of being dominated by money and greed at the expense of the holiday's more important values. Frustrations over these issues and others can lead to a rise in Christmastime social problems. | |||

Most [[economists]] agree, however, that Christmas produces a [[deadweight loss]] under [[orthodox]] [[microeconomic theory]], associated with the surge in gift-giving. This loss is calculated as the difference between what the gift giver spent on the item and what the gift receiver would have paid for the item. It is estimated that in 2001 Christmas resulted in a $4 billion deadweight loss, in the U.S. alone, as a result of the gift-giving <ref>{{cite journal | title=The Deadweight Loss of Christmas | journal=American Economic Review | year=December 1993 | volume=83 | issue=5}}</ref><ref> | |||

{{cite journal | title=Is Santa a deadweight loss? | journal=The Economist | year=2001 | issue= [[December 20]] | url=http://www.economist.com/finance/displayStory.cfm?Story_ID=885748}}</ref>, although there are a number of confounding factors. This analysis is sometimes used to discuss possible flaws in current microeconomic theory. | |||

In [[North America]], film studios release many high budget movies in the holiday season, many of them being Christmas films, [[fantasy]] movies or high-tone dramas with rich production values, both to capture holiday crowds and to position themselves for [[Academy Awards]]. This is the second most lucrative season for the industry after summer. Christmas-specific movies generally open in late [[November]] or early [[December]] as their themes and images are not so popular once the season is over; often the [[home video]] releases of these films are delayed until the following Christmas season. The winter movie season spans from the first week of November until mid-February. | |||

Revision as of 05:53, 17 December 2020

Christmas (literally, the Mass of Christ) is a traditional holiday celebrating the birth of Jesus with both religious and secular aspects, commonly observed on 25 December. In most Eastern Orthodox Churches, even where the civil calendar used is the Gregorian, the event is observed according to the Julian calendar, which coincides with the predominant reckoning of 7 January. Celebrated mostly by Christians, the holiday is based on the traditional —though not accurate— birth of Jesus, as 25 December. Recent data has concluded that Jesus was likely born earlier, circa 8 BC – 2 BC, not to mention at a different time of year. Christ's birth, or nativity, was said by his followers to fulfill the prophecies of Judaism that a messiah would come, from the house of David, to redeem the world from sin. Efforts to decide upon a date on which to celebrate his birth began some centuries later.

The word Christmas is a contraction of Christ's Mass, derived from the Old English Cristes mæsse. It is often abbreviated Xmas, probably because X resembles the Greek letter Χ (chi) which has often historically been used as an abbreviation for Christ (Χριστός in Greek).

Christmas has acquired many secular aspects, which are sometimes celebrated as often—or more—than the birth of Jesus. Many Christmas traditions originated with pre-Christian observances that were syncretised into Christianity. Examples of this process are the northern European Yule, and the Winter Solstice celebration found in many older as well as recent pagan celebrations.

In Western countries, Christmas has become the most economically significant holiday of the year. It is largely characterized by gifts being exchanged between friends and family members, and the appearance of Santa Claus. Various local and regional Christmas traditions are still practised, despite the widespread influence of American, British and Australian Christmas motifs disseminated by globalization, popular literature, television, and other media.

The Nativity

The story of Christ's birth has been handed down for centuries, based mainly on the Christian gospels of Matthew and Luke. The gospels of Mark and John do not address the childhood of Jesus, and those of Matthew and Luke highlight different events.

According to Luke, Mary learns from an angel that the Holy Spirit has caused her to be with child. Shortly thereafter, she and her husband Joseph leave their home in Nazareth to travel about 150 kilometres (90 miles) to Joseph's ancestral home, Bethlehem, to enroll in the census ordered by the Roman emperor, Augustus. Finding no room in inns in the town, they set up lodgings in a stable in Bethlehem in Judea. There Mary gives birth to Jesus. Jesus' being born in Bethlehem fulfills the prophecy of the Book of Micah. Luke's Gospel has some references to historic events at this time, saying "In these days the Roman emperor Augustus ordered to excise a counting of all population in the world" (Lk 2,1), but the only known census was in the year AD 6.

Matthew's gospel begins by telling the genealogy and birth of Jesus, and then moves to the coming of the Magi (sometimes erroneously translated simply as wise men - some translations add the number three, although the number is not actually specified) from the East to Bethlehem. Matthew mentions no trek to Bethlehem from Nazareth. The Magi first arrive in Jerusalem and report to the king of Judea, Herod the Great, that they have seen a star, now called the Star of Bethlehem, heralding the birth of a king. Further inquiry leads them to Bethlehem of Judea and the home of Mary and Joseph. They present Jesus with treasures of "gold, frankincense, and myrrh". While staying the night, the Magi have a dream that contains a divine warning that King Herod has murderous designs on the child. Resolving to hinder the ruler, they go home without telling Herod of the success of their mission. Matthew then reports that the family next flees to Egypt to escape the murderous rampage of Herod, who has decided to have all children of Bethlehem under the age of two killed in order to eliminate any local rivals to his power. After Herod's death, Jesus and his family return from Egypt, but fearing the hostility of the new Judean king (Herod's son Archelaus) they go instead to Galilee and settle in Nazareth.

Another aspect of Christ's birth which has passed from the gospels into popular lore is the announcement by angels to nearby shepherds of Jesus's birth. Some Christmas carols refer to the shepherds observing a bright star directly over Bethlehem, and following it to the birthplace. The Magi, who Matthew also reports seeing a giant star, have been variously interpreted as wise men or as kings. They are supposed to have come from Arabia or Persia, where they might have obtained their particular gifts. Through the years astronomers and historians have offered conflicting explanations of what combination of traceable celestial events might explain the appearance of a giant star that had never before been seen.[1]

Theories on the origins of Christmas

Many different dates have been suggested for the celebration of Christmas. The theories for the reason Christmas is celebrated on December 25 are many and varied; none are universally accepted.

The Romans marked the winter solstice or bruma on December 25, although on the Roman calendar the date of the astronomical solstice varies between December 21 (the modern date) and December 24. Various cultures believed that their sun god was reborn on the solstice, the shortest day of the year.

It is alleged that, according to Celtic Mythology, the sun god was crucified on the winter solstice, and three days later, as the days grew longer again, he rose from the dead. It is said that this was the origin of the Celtic cross, symbolising the crucified sun god, thus making it a few thousand years older than Christianity. Nevertheless, there is no record of the Celts actually ever practicing crucifixion or stories of any crucifixion of a "Celtic Sun God" before 19th century source. Crosses and circles are found worldwide as solar symbol, whether or not a particular culture practiced crucifixion.

Christianity, and thus Christmas, formed during the Roman Empire. The Romans honored Saturn, the ancient god of agriculture, each year on December 17. In a festival called Saturnalia, they glorified the "golden age" when the god Saturn ruled. This festival was eventually extended to six days. During Saturnalia the Romans feasted, postponed all business and warfare, exchanged gifts, and temporarily freed their slaves. Such traditions resemble those of Christmas and are used to establish a link between the two holidays. These and other winter festivities continued through January 1, the festival of Kalends, when Romans marked the day of the new moon and the first day of the month as well as the beginning of the religious year.

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, Christmas is not included in Irenaeus's nor Tertullian's list of Christian feasts, the earliest known lists of Christian feasts. The earliest evidence of celebration is from Alexandria, in about 200, when Clement of Alexandria says that certain Egyptian theologians "over curiously" assign not just the year but also the actual day of Christ's birth as 25 Pachon (May 20) in the twenty-eighth year of Augustus.[2] By the time of the Council of Nicaea in 325, the Alexandrian church had fixed a dies Nativitatis et Epiphaniae. The December feast reached Egypt in the fifth century. In Jerusalem, the fourth century pilgrim Egeria from Bordeaux witnessed the Feast of the Presentation, forty days after January 6, which must have been the date of the Nativity there. At Antioch, probably in 386, St. John Chrysostom urged the community to unite in celebrating Christ's birth on December 25, a part of the community having already kept it on that day for at least ten years.

In the late Roman Empire, the festival of Sol Invictus was celebrated December 25. In 350, Pope Julius I ordered that the birth of Christ be celebrated on the same date.

Some scholars maintain that December 25 was only adopted in the 4th century as a Christian holiday after Roman Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity to encourage a common religious festival for both Christians and pagans. Perusal of historical records indicates that the first mention of such a feast in Constantinople was not until 379, under Gregory Nazianzus. In Rome, it can only be confirmed as being mentioned in a document from approximately 350 but without any mention of sanction by Emperor Constantine.

An alternative theory asserts that the date of Christmas is based on the date of Good Friday, the day Jesus died. Since the exact date of Jesus' death is not stated in the Gospels, early Christians sought to calculate it, and arrived at either March 25 or April 6. To then calculate the date of Jesus' birth, they followed the ancient idea that Old Testament prophets died at an "integral age" — either an anniversary of their birth or of their conception. They reasoned that Jesus died on an anniversary of the Incarnation (his conception), so the date of his birth would have been nine months after the date of Good Friday — either December 25 or January 6. Thus, rather than the date of Christmas being appropriated from pagans by Christians, the opposite is held to have occurred.[3][4]

Another extremely popular cult of Persian origin, in those days was that of Mithras. The similarities between Jesus and Mithras are many. Mithras was born on December 25 of virgin birth, the son of the primary Persian deity, Ahura-Mazda. His birth was witnessed by shepherds and magi. He was reputed to have raised the dead, healed the sick and cast out demons. He had a Lord's Supper. His day of worship was Sunday. He was killed and resurrected, returned to heaven on the spring equinox after a last meal with his 12 disciples (representing the signs of the zodiac), eating "mizd" - a piece of bread marked with a cross (an almost universal symbol of the sun). The Mithraic cult peaked around the year 300 AD when it became the official religion of the empire. At that time, in every town and city, in every military garrison and outpost from Syria to the Scottish frontier, was to be found a Mithraeum and officiating priests of the cult. This is not to suggest that the Mithraic cult was the only factor in this syncretization, many pagan gods had similar aspects of mythology (e.g. resurrection, virgin mother etc).

Early Christians chiefly celebrated the Epiphany, when the baby Jesus was visited by the Magi (and this is still a primary time for celebration in Argentina, Spain and Armenia). Historians are unsure exactly when Christians first began celebrating the Nativity of Christ. At times it was forbidden by Protestant churches until after the 1800s because of its association with Catholicism.

Some Christmas traditions, particularly those in Scandinavia, have their origin in the Germanic Yule celebration. Christmas is still known as Yule (or: Jul) in Scandinavian countries.

When was the original Christmas?

- See also: Chronology of Jesus

Early Christians sought to calculate the date of Christ's birth based on the idea that Old Testament prophets died either on an anniversary of their birth or of their conception. They reasoned that Jesus died on an anniversary of his conception, so the date of his birth was nine months after the date of Good Friday, either December 25 or January 6.

St. Hippolytus, who was already knowledgeably defending the faith in writing at the start of the third century, said that Christ was born Wednesday, December 25, in the 42nd year of Augustus' reign (see his Commentary on Daniel, circa 204, Bk. 4, Ch. 23).

Additional calculations are made based on the six-year almanac of priestly rotations, found among the Dead Sea Scrolls. Some believe that this almanac lists the week when John the Baptist's father served as a high priest. As it is implied that John the Baptist could only have been conceived during that particular week, and as his conception is believed to be tied to that of Jesus, it is claimed that an approximate date of December 25 can be arrived at for the birth of Jesus. However, most scholars (e.g. Catholic Encyclopedia in sources) believe this calculation to be unreliable as it is based on a string of assumptions.

The apparition of the angel Gabriel to Zechariah, announcing that he was to be the father of John the Baptist, was believed to have occurred on Yom Kippur. This was due to a belief (not included in the Gospel account) that Zechariah was a high priest and that his vision occurred during the high priest's annual entry into the Holy of Holies. If John's conception occurred on Yom Kippur in late September, then his birth would have been in late June. If John's birth was on the date ascribed by tradition, June 24, then the Annunciation to the Blessed Virgin Mary, said by the Gospel account to have occurred three month's before John's birth, would have been in late March. (Tradition fixed it on March 25.) The birth of Jesus would then have been on December 25, nine months after his conception. As with the previous theory, proponents of this theory hold that Christmas was a date of significance to Christians before it was a date of significance to pagans.

Dates of celebration

Efforts to fix a date for the birth of Christ began some two centuries after his death, as the Catholic Church began to establish its traditions. Christmas is now celebrated on December 25 in Catholic and Catholic-derived churches (Roman and Protestant), and thus in most of the Western world. In the nations of the former Soviet Union, the Balkans, and other regions where the Eastern Rite churches are more prominent, Christmas is now celebrated on January 7. This date results from their having accepted neither the reforms of the Gregorian calendar nor the Revised Julian calendar, with their ecclesiastic December 25 thus falling on the civil date of January 7 from 1900 to 2099. The Armenian Church places much more emphasis on the Epiphany, the visitation by the Magi, than on Christmas. This calendrical difference has led to confusion on the part of those unfamiliar with the older calendar.

The Orthodox churches begin preparing for Christmas with a fast that begins 40 days before Christmas and ends with Christmas, dubbed the "Feast of the Nativity of our Lord, God, and Saviour Jesus Christ." In the U.S. and Canada, some Orthodox dioceses allow the parish priest or parish to decide which of the two calendars (i.e., Gregorian versus old Julian) to follow at the parish level and hence the timing of Christmas Day. Armenian Christians celebrate Christmas on January 6th except those in Jerusalem, who still use the old calendar and celebrate Christmas on January 18.[5]

Dates for the more secular aspects of the Christmas celebration are similarly varied. In the United Kingdom, the Christmas season traditionally runs for twelve days beginning on Christmas Day. These twelve days of Christmas, a period of feasting and merrymaking, end on Twelfth Night, the eve of the Feast of the Epiphany. This period corresponds with the liturgical season of Christmas. Medieval laws in Sweden declared a Christmas peace (julefrid) to be twenty days, during which fines for robbery and manslaughter were doubled. Swedish children still celebrate a party, throwing out the Christmas tree (julgransplundring), on the 20th day of Christmas (January 13, Knut's Day).

In practice, the Christmas festive period has grown longer in some countries, including the United States and the United Kingdom, and now begins many weeks before Christmas, allowing more time for shopping and get-togethers. It often extends beyond Christmas Day up to New Year's Day, this later holiday having its own parties. In the Philippines, radio stations usually start playing Christmas music during what is called the "-ber months" (September, October, etc.); this usually marks the start of the Christmas season.

Countries that celebrate Christmas on December 25 recognize the previous day as Christmas Eve, and vary on the naming of December 26. In the Netherlands, Germany, Scandinavia, Lithuania and Poland, Christmas Day and the following day are called First and Second Christmas Day. In many European and Commonwealth countries, December 26 is referred to as Boxing Day, while in Finland, Ireland, Italy, Romania, Austria and Catalonia (Spain) it is known as St. Stephen's Day. In Canadian French, the December 26 holiday is generally referred to as Lendemain de Noël (which literally means "the day after Christmas").

Regional customs and celebrations

A plethora of customs with secular, religious, or national aspects surround Christmas, varying from country to country. Most of the familiar traditional practices and symbols of Christmas originated in Germanic countries, including the now omnipresent Christmas tree, the Christmas ham, the Yule Log, holly, mistletoe, and the giving of presents to friends and relatives. These practices and symbols were adapted or appropriated by Christian missionaries from the earlier Germanic pagan midwinter holiday of Yule. This celebration of the winter solstice was widespread and popular in northern Europe long before the arrival of Christianity, and the word for Christmas in the Scandinavian languages is still today the pagan jul (=yule).

Rather than attempting to suppress every pagan tradition, Pope Gregory I allowed Christian missionaries to synthesize them with Christianity, allowing many pagan traditions to become a part of Christmas.[6]

The dynamic relationship between religious and governmental authorities and celebrators of Christmas continued through the years. Places where conservative Christian theocracies flourished, as in Cromwellian England and in the early New England colonies, were among those where celebrations were suppressed.[7]

After the Russian Revolution, Christmas celebrations were banned in the Soviet Union for the next seventy-five years.

Several Christian denominations, notably the Jehovah's Witnesses, some Puritan groups, and some fundamentalist Christians, view Christmas as a pagan holiday not sanctioned by the Bible and refuse to celebrate or recognize it in any way. Incidentally, this was the practice of the Puritans in 17th and 18th Century England and the American Colonies. Christmas was not widely celebrated in New England until after the middle of the 19th Century.

In Commonwealth countries in the southern hemisphere, Christmas is still celebrated on 25 December, despite this being the height of their summer season. This clashes with the traditional winter iconography, resulting in anachronisms such as a red fur-coated Santa Claus surfing in for a turkey barbecue on Australia's Bondi Beach. Japan has largely adopted the western Santa Claus for its secular Christmas celebration, but their New Year's Day is considered the more important holiday. Christmas is also known as bada din (the big day) in Hindi, and revolves there around Santa Claus and shopping. In South Korea, Christmas is celebrated as an official holiday.

Religious customs and celebrations

The religious celebrations begin with Advent, the anticipation of Christ's birth, around the start of December. (In most western churches, Advent starts the 4th Sunday before Christmas Day, and thus can last for 21 to 28 days.) These observations may include Advent carols and Advent calendars, sometimes containing sweets and chocolate for children. Christmas Eve and Christmas Day services may include a midnight mass or a Mass of the Nativity, and feature Christmas carols and hymns.

Secular customs

Christmas customs and traditions transmitted through mass culture have been adopted by Christians and non-Christians alike, particularly in North America.

Since the customs of Christmas celebration largely evolved in northern Europe, many are associated with the Northern Hemisphere winter, the motifs of which are prominent in Christmas decorations and in Santa Claus stories.

Santa Claus and other bringers of gifts

Gift-giving is a near-universal part of Christmas celebrations. The concept of a mythical figure who brings gifts to children derives from Saint Nicholas, a bishop of Myra in fourth century Lycia, Asia Minor. He made a pilgrimage to Egypt and Palestine in his youth and soon thereafter became Bishop of Myra. He was imprisoned during the persecution of Diocletian and released after the accession of Constantine. He may have been present at the Council of Nicaea, though there is no record of his attendance. He died on December 6 of 345 or 352. In 1087, Italian merchants stole his deceased body at Myra and brought it to Bari in Italy. His relics are still preserved in the church of San Nicola in Bari. To this day, an oily substance known as Manna di S. Nicola, which is highly valued for its medicinal powers, is said to flow from his relics [8].

The Dutch modeled a gift-giving Saint Nicholas on the eve of his feast day on December 6. In North America, other colonists adopted the feast of Sinterklaas brought by the Dutch into their Christmas holiday, and Sinterklaas became Santa Claus, or Saint Nick, known in some West African and the UK countries as Father Christmas. In the Anglo-American tradition, this jovial fellow arrives on Christmas Eve on a sleigh pulled by reindeer, and lands on the roofs of houses. He then climbs down the chimney, leaves gifts for the children, and eats the food they leave for him. He spends the rest of the year making toys and keeping lists on the behaviour of the children.

One belief in the United Kingdom, United States, and other countries passed down through the generations is the idea of lists of good children and bad children. Throughout the year, Santa supposedly adds names of children to either the good or bad list depending on their behaviour. When it gets closer to Christmas time, parents use the belief to encourage children to behave well. Those who are on the bad list and whose behaviour has not improved before Christmas are said to receive a booby prize, such as a piece of coal or a switch with which their parents beat them, rather than presents.

The French equivalent of Santa, Père Noël, evolved along similar lines, eventually adopting the Santa image Haddon Sundblom painted for a worldwide Coca-Cola advertising campaign in the 1930s. In some cultures Santa Claus is accompanied by Knecht Ruprecht, or Black Peter. In some versions, elves in a toy workshop make the holiday toys, and in some he is married to Mrs. Claus. Many shopping malls in North America, the United Kingdom, and Australia have a holiday mall Santa Claus whom children can visit to ask for presents.

In many countries, children leave empty containers for Santa to fill with small gifts such as toys, candy, or fruit. In the United Kingdom, the United States, and Canada children hang a Christmas stocking by the fireplace on Christmas Eve because Santa is said to come down the chimney the night before Christmas to fill them. In other countries, children place their empty shoes out for Santa to fill on the night before Christmas, or for Saint Nicholas to fill on December 5 before his feast day the next day. Gift giving is not restricted to these special gift-bringers, as family members and friends also bestow gifts on each other.

Timing of gifts

In many countries, Saint Nicholas's Day remains the principal day for gift giving. In such places, including the Netherlands, Christmas Day remains more a religious holiday. In much of Germany, children put shoes out on window sills on the night of December 5, and find them filled with candy and small gifts the next morning. The main day for gift giving, however, is December 24, when gifts are brought by Santa Claus or are placed under the Christmas tree. Same in Hungary, except that the Christmas gifts are usually brought by Jesus, not by Santa Claus. In other countries, including Spain, gifts are brought by the Magi at Epiphany on January 6. In Poland, Santa Claus (Polish: Święty Mikołaj) gives gifts at two occasions: on the night of December 5 (so that children find them on the morning of December 6) and on Christmas Eve, December 24, (so that children find gifts that same day). In Finland Joulupukki personally meets children and gives gifts on December 24. In Russia, Grandfather Frost brings presents on New Year's Eve, and these are opened on the same night.

One of the many customs of gift timing is suggested by the song "Twelve Days of Christmas", celebrating an old British tradition of gifts each day from Christmas to Epiphany. In most of the world, Christmas gifts are given at night on Christmas Eve or in the morning on Christmas Day. Until recently, gifts were given in the UK to non-family members on Boxing Day.

Declaration of Christmas Peace

Declaration of Christmas Peace has been a tradition in Finland from the Middle Ages every year, except in 1939 due to the war. The declaration takes place on the Old Great Square of Turku, Finland's official Christmas City and former capital, at noon on Christmas Eve. It is broadcast in Finnish radio (since 1935) and television and nowadays also in some foreign countries.

The declaration ceremony begins with the hymn Jumala ompi linnamme (Martin Luther's Ein` feste Burg ist unser Gott) and continues with the Declaration of Christmas Peace read from a parchment roll:

"Tomorrow, God willing, is the graceful celebration of the birth of our Lord and Saviour; and thus is declared a peaceful Christmas time to all, by advising devotion and to behave otherwise quietly and peacefully, because he who breaks this peace and violates the peace of Christmas by any illegal or improper behaviour shall under aggravating circumstances be guilty and punished according to what the law and statutes prescribe for each and every offence separately. Finally, a joyous Christmas feast is wished to all inhabitants of the city."

Recently there have also been declarations of Christmas peace for forest animals in many cities and municipalities, restricting hunting during the holiday.

Christmas cards

Christmas cards are extremely popular in New Zealand, Australia, Canada, the United States, and Europe, in part as a way to maintain relationships with distant relatives, friends, and business acquaintances. Many families enclose an annual family photograph or a family newsletter summarizing the adventures and accomplishments of family members during the preceding year.

Decorations

Decorating a Christmas tree with lights and ornaments and the decoration of the interior of the home with garlands and evergreen foliage, particularly holly and mistletoe, are common traditions. In Australia, North and South America and to a lesser extent Europe, it is traditional to decorate the outside of houses with lights and sometimes with illuminated sleighs, snowmen, and other Christmas figures.

Since the 19th century, the traditional Christmas flower has been the winter-blooming poinsettia. Other popular holiday plants include holly, mistletoe, red amaryllis, and Christmas cactus.

Municipalities often sponsor decorations as well, hanging Christmas banners from street lights or placing Christmas trees in the town square. In the US, decorations once commonly included religious themes. This practice has led to much adjudication, as some say it amounts to the government endorsing a religion. In 1984 the US Supreme Court ruled that a city-owned Christmas display including a Christian nativity scene was depicting the historical origins of Christmas and was not in violation of the First Amendment [9].

Although Christmas decorations, such as the tree, are essentially secular in character in some parts of the world, e.g. in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, such display is banned on the grounds that the symbols are of Christianity (which is proscribed).

Social aspects and entertainment

In many countries, businesses, schools, and communities have Christmas parties and dances during the several weeks before Christmas Day. Christmas pageants, common in Latin America, may include a retelling of the story of the birth of Christ. Groups may go caroling, visiting neighborhood homes to sing Christmas songs. Others are reminded by the holiday of their kinship with the rest of humanity and do volunteer work or hold fundraising drives for charities.

On Christmas Day or Christmas Eve, a special meal of Christmas dishes is usually served, for which there are different traditional menus in many country. In some regions, particularly in Eastern Europe, these family feasts are preceded by a period of fasting. Candy and treats are also part of the Christmas celebration in many countries.

Because of the focus on celebration, friends, and family, people who are without these, or who have recently suffered losses, are more likely to suffer from depression during Christmas. This increases the demands for counseling services during the period.

It is widely believed that suicides and murders spike during the holiday season. However, the peak months for suicide are May and June. Because of holiday celebrations involving alcohol, drunk driving-related fatalities may also increase.

Non-Christians in predominantly Christian nations may have few choices for entertainment around Christmas, as stores close and friends depart for vacations. The cliché recreation for them is "movies and Chinese food"; movie theaters remaining open to bring in holiday box office dollars and Chinese (and presumably Buddhist, et al.) establishments being less likely to close for the "big day".

Christmas carol media

Template:Multi-listen start Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen end

Christmas in the arts and media

Many fictional Christmas stories capture the spirit of Christmas in a modern-day fairy tale, often with heart-touching stories of a Christmas miracle. Several have become part of the Christmas tradition in their countries of origin.

Among the most popular are Tchaikovsky's ballet The Nutcracker and Charles Dickens's novel A Christmas Carol. The Nutcracker tells of a nutcracker that comes to life in a young German girl's dream. Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol is the tale of curmudgeonly miser Ebenezer Scrooge. Scrooge rejects compassion and philanthropy, and Christmas as a symbol of both, until he is visited by the ghosts of Christmas Past, Present and Future, who show him the consequences of his ways. Dickens is sometimes credited with shaping the modern Christmas of English-speaking countries of Christmas trees, plum pudding, and Christmas carols with shaping the movement to close businesses on Christmas Day.

Just as Dickens shaped Christmas traditions, 19th century cartoonist Thomas Nast gave Santa his familiar form (Harper's Weekly, 1863). "A Visit from St. Nicholas" (Sentinel, 1823, authorship by either Henry Livingston Jr. or Clement Clarke Moore and popularly known as "The Night Before Christmas") supplied the rotund Santa and his sleigh landing on rooftops on Christmas Eve.

In 1881, the Swedish magazine Ny Illustrerad Tidning published Viktor Rydberg's poem Tomten featuring the first painting by Jenny Nyström of the traditional Swedish mythical character tomte which she turned into the friendly white-bearded figure associated with Christmas. Her figure was further developed in 1931 by Haddon Sundblom for the Coca-Cola Company.

Although Christmas icons have become widespread through television and movies, Christmas is still a time when national traditions are strong, and both Santa's appearance and the stories told vary from country to country. Some Scandinavian Christmas stories are less cheery than Dickens's, notably H. C. Andersen's The Little Match Girl. A destitute little slum girl walks barefoot through snow-covered streets on Christmas Eve, trying in vain to sell her matches, and peeking in at the celebrations in the homes of the more fortunate. She dares not go home because her father is drunk. Unlike the principals of Anglophone Christmas lore, she meets a tragic end.

Many Christmas stories have been popularized as movies and TV specials. Since the 1980s, many video editions are sold and resold every year during the holiday season. A notable example is the film It's a Wonderful Life, which turns the theme of A Christmas Carol on its head. Its hero, George Bailey, is a businessman who sacrificed his dreams to help his community. On Christmas Eve, a guardian angel finds him in despair and prevents him from committing suicide, by magically showing him how much he meant to the world around him. Perhaps the most famous animated production is A Charlie Brown Christmas wherein Charlie Brown tries to address his feeling of dissatisfaction with the holidays by trying to find a deeper meaning to them. The humorous A Christmas Story (1983) has become a holiday classic and is shown for 24 hours straight from Christmas Eve to Christmas Day on TNT/TBS.