Simon Stevin: Difference between revisions

imported>Paul Wormer |

imported>Paul Wormer (→Work) |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

Stevin's most important work: ''De beghinselen der weeghconst'' [The principles of the art of weighing] appeared in in 1586. By ''weeghconst'' Stevin means the part of mechanics that is called [[statics]]. This field was founded by [[Archimedes]] and Stevin continued his theoretical work on the forces that keep solid bodies in their place. Stevin treats a solid body on a sloping plane and decomposes the gravitational force in a component perpendicular to the plane and one that keeps the body in rest on the slope; doing this he introduced the "the parallelogram of forces". See the figure for a practical application. | Stevin's most important work: ''De beghinselen der weeghconst'' [The principles of the art of weighing] appeared in in 1586. By ''weeghconst'' Stevin means the part of mechanics that is called [[statics]]. This field was founded by [[Archimedes]] and Stevin continued his theoretical work on the forces that keep solid bodies in their place. Stevin treats a solid body on a sloping plane and decomposes the gravitational force in a component perpendicular to the plane and one that keeps the body in rest on the slope; doing this he introduced the "the parallelogram of forces". See the figure for a practical application. | ||

{{Image|Stevin weeghdaet.JPG|left|275px|<small>From the ''Weeghdaet'' (Practice of weighing | {{Image|Stevin weeghdaet.JPG|left|275px|<small>From the ''Weeghdaet'' (Practice of weighing), p. 31</small>}} | ||

In the same year (1586) Stevin published a report on his experiment, performed in [[Delft]] together with the father of [[Hugo Grotius]], in which two lead spheres, one 10 times as heavy as the other, were dropped from a church tower. After falling a distance of 30 feet, the balls landed on a wooden plank. The two observers heard one bang only and concluded that the two balls fell with equal speed. Also at that time he applied for patents for several civil engineering inventions, such as improvements for windmills used for drainage. | In the same year (1586) Stevin published a report on his experiment, performed in [[Delft]] together with the father of [[Hugo Grotius]], in which two lead spheres, one 10 times as heavy as the other, were dropped from a church tower. After falling a distance of 30 feet, the balls landed on a wooden plank. The two observers heard one bang only and concluded that the two balls fell with equal speed. Also at that time he applied for patents for several civil engineering inventions, such as improvements for windmills used for drainage. | ||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

In 1594 appeared the ''Appendice Algebraïque'', an eight-page pamphlet. In it he gave for the first time his famous solution for equations of the third degree by means of successive approximations. The only extant copy of this work was lost in a 1914 fire. | In 1594 appeared the ''Appendice Algebraïque'', an eight-page pamphlet. In it he gave for the first time his famous solution for equations of the third degree by means of successive approximations. The only extant copy of this work was lost in a 1914 fire. | ||

Around 1590 Stevin became adviser and tutor in mathematics and natural sciences of the ''Stadtholder'' [[Maurice, Prince of Orange]], who had succeeded his father [[William the Silent]] as leader of the Dutch Revolt. Stevin instructed Maurice in various subjects and wrote teaching material for him that later was published in ''Wisconstighe Ghedachtenissen'' [Mathematical Memoirs] (1605-1608). He constructed for Maurice a famous sailing-carriage holding 28 passengers, that on the flat Dutch beach could cover the distance from [[Scheveningen]] to [[Petten]] (85 km) supposedly in two hours.<ref>George Sarton, ''Simon Stevin of Bruges (1548-1620)'', Isis, Vol. '''21''', p. 241 (1934), reproduces a 17th century engraving of the carriage and mentions that Hugo Grotius, the son of a friend of Stevin's, wrote a poem about it. However, A. J. Kox in ''Van Stevin tot Lorentz'', Intermediair Bibliotheek, Amsterdam (1980) calls the story of the two hour trip strongly exaggerated.</ref> A sustained speed of more than 40 km/h was incredible in those days. Also for Maurice he wrote in 1594 ''Stercktenbouwing'' (the building of fortifications). | Around 1590 Stevin became adviser and tutor in mathematics and natural sciences of the ''Stadtholder'' [[Maurice, Prince of Orange]], who had succeeded his father [[William the Silent]] as leader of the Dutch Revolt. Stevin instructed Maurice in various subjects and wrote teaching material for him that later was published in ''Wisconstighe Ghedachtenissen'' [Mathematical Memoirs] (1605-1608). He constructed for Maurice a famous sailing-carriage holding 28 passengers, that on the flat Dutch beach could cover the distance from [[Scheveningen]] to [[Petten]] (85 km) supposedly in two hours.<ref>George Sarton, ''Simon Stevin of Bruges (1548-1620)'', Isis, Vol. '''21''', p. 241 (1934), reproduces a 17th century engraving of the carriage and mentions that Hugo Grotius, the son of a friend of Stevin's and who made the trip, wrote a poem about it. However, A. J. Kox in ''Van Stevin tot Lorentz'', Intermediair Bibliotheek, Amsterdam (1980) calls the story of the two hour trip strongly exaggerated.</ref> A sustained speed of more than 40 km/h was incredible in those days. Also for Maurice he wrote in 1594 ''Stercktenbouwing'' (the building of fortifications). | ||

Upon invitation of the city of Dantzig ([[Gdansk]]) he traveled to Poland in the summer of 1591, probably to give advise about Dantzig's harbor. | |||

Stevin wrote on astronomy and defended the sun-centered system of Copernicus in ''De Hemelloop'' (the course of heaven), that appeared in 1608 as part of the ''Wisconstighe Ghedachtenissen''. Stevin's [[Copernicus|Copernicanism]] met resistance from influential Calvinist theologians, such as [[Ubbo Emmius]]. | In 1600 Stevin was asked to compose an instruction for a new school of engineers as part of Leiden university. The new course was written in Dutch so that also students who did not know Latin could follow it. | ||

Stevin wrote on astronomy and defended the sun-centered system of Copernicus in ''De Hemelloop'' (the course of heaven), that appeared in 1608 as part of the ''Wisconstighe Ghedachtenissen''. Stevin's [[Copernicus|Copernicanism]] met some resistance from influential Calvinist theologians, such as [[Ubbo Emmius]], but this was uncomparable to the censoring eight years later of [[Galileo Galilei]] who shared Stevin's Copernicanism. | |||

Stevin loved the Dutch language and was a purist. He invented many words that are still current in Dutch (a famous example is ''wisconst'' for mathematics, in modern Dutch ''wiskunde''—literally the art of certainties; ''wisconstigh'' means mathematical). After the mid 1590s he refused to write in any other language than Dutch, which gave him a lower international profile than a man of his talents deserved. | Stevin loved the Dutch language and was a purist. He invented many words that are still current in Dutch (a famous example is ''wisconst'' for mathematics, in modern Dutch ''wiskunde''—literally the art of certainties; ''wisconstigh'' means mathematical). After the mid 1590s he refused to write in any other language than Dutch, which gave him a lower international profile than a man of his talents deserved. | ||

Revision as of 10:41, 8 January 2010

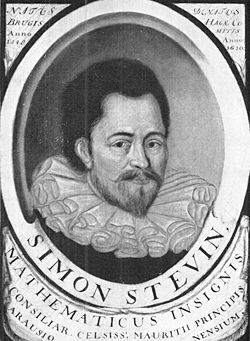

Simon Stevin (1548 – 1620) was a Flemish-Dutch engineer and mathematician, who was one of the first to write rational numbers as decimal fractions (although he did not yet use the decimal point as place holder). He was the first to decompose forces by using geometric drawings that are equivalent to what we now call "the parallelogram of forces" (see vector addition) and he did experiments—a few years before Galileo Galilei—that refuted Aristotle's law of free fall. That is, he found that heavy bodies do not fall faster than light ones.[1] Stevin excelled in mathematical theory and engineering applications.

Life

Simon Stevin was born in Bruges, one of the important cities of Flanders, the Dutch speaking part of Belgium. He was a natural child of Antheunis Stevin and Cathelyne van der Poort. He worked as a merchant's bookkeeper in Antwerp, the largest city in Flanders, and later as financial clerk in the administration of the Vrije van Brugge, the rural district surrounding Bruges.

For unclear reasons he moved around 1580 to Leiden in the The Netherlands. He was matriculated as a student in the University of Leiden on February 16th, 1583. Simon Stevin had four children. As to his marriage we only know of a notice of marriage with Catherina Cray at Leyden on April 10th 1616, when he was 68 years old (but Simon Stevin had children already before 1616). Stevin died in 1620; the exact date nor the place is known but he passed away between February 20th and April 8th and most probably in the Hague.

Work

While still in Flanders, Stevin composed world's first table of interests Tafelen van Interest (1582).

In 1585 he published a booklet, De Thiende [The Tenth], in which he presented an elementary account of decimal fractions and their daily use. His booklet starts with:

Den Sterrekyckers, Landt meters, Tapijtmeters, Wijnmeters, Lichaemmeters int ghemeene, Muntmeesters, ende allen Cooplieden, wenscht Simon Stevin Gheluck.

[Simon Stevin wishes luck to Stargazers, Surveyors, Carpet-measurers, Wine-gaugers, Stereometers in general, Mintmasters and all Merchants.]

making clear that he had very practical applications in mind with his new arithmetic tool. Although he did not invent decimal fractions and his notation was rather unwieldy, he established their use in day-to-day mathematics. Robert Norton published an English translation of De Thiende in London in 1608. It was entitled Disme, the Arts of Tenths or Decimall Arithmetike. It is this work that inspired Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, and the first mint master David Rittenhouse to deviate from the British currency system and to propose a decimal currency for the United States, a country that otherwise uses the imperial system for its units. (One tenth of a dollar is a dime; the name is derived from disme).

In 1585 Stevin published L'arithmétique. In it Stevin presented a unified treatment for solving quadratic equations and a method for finding approximate solutions to algebraic equations of all degrees. He considered all kinds of real numbers on an equal footing—natural numbers, roots (the majority of which are irrational numbers), and negative numbers. He did not accept complex numbers.

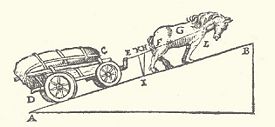

Stevin's most important work: De beghinselen der weeghconst [The principles of the art of weighing] appeared in in 1586. By weeghconst Stevin means the part of mechanics that is called statics. This field was founded by Archimedes and Stevin continued his theoretical work on the forces that keep solid bodies in their place. Stevin treats a solid body on a sloping plane and decomposes the gravitational force in a component perpendicular to the plane and one that keeps the body in rest on the slope; doing this he introduced the "the parallelogram of forces". See the figure for a practical application.

In the same year (1586) Stevin published a report on his experiment, performed in Delft together with the father of Hugo Grotius, in which two lead spheres, one 10 times as heavy as the other, were dropped from a church tower. After falling a distance of 30 feet, the balls landed on a wooden plank. The two observers heard one bang only and concluded that the two balls fell with equal speed. Also at that time he applied for patents for several civil engineering inventions, such as improvements for windmills used for drainage.

In 1594 appeared the Appendice Algebraïque, an eight-page pamphlet. In it he gave for the first time his famous solution for equations of the third degree by means of successive approximations. The only extant copy of this work was lost in a 1914 fire.

Around 1590 Stevin became adviser and tutor in mathematics and natural sciences of the Stadtholder Maurice, Prince of Orange, who had succeeded his father William the Silent as leader of the Dutch Revolt. Stevin instructed Maurice in various subjects and wrote teaching material for him that later was published in Wisconstighe Ghedachtenissen [Mathematical Memoirs] (1605-1608). He constructed for Maurice a famous sailing-carriage holding 28 passengers, that on the flat Dutch beach could cover the distance from Scheveningen to Petten (85 km) supposedly in two hours.[2] A sustained speed of more than 40 km/h was incredible in those days. Also for Maurice he wrote in 1594 Stercktenbouwing (the building of fortifications).

Upon invitation of the city of Dantzig (Gdansk) he traveled to Poland in the summer of 1591, probably to give advise about Dantzig's harbor.

In 1600 Stevin was asked to compose an instruction for a new school of engineers as part of Leiden university. The new course was written in Dutch so that also students who did not know Latin could follow it.

Stevin wrote on astronomy and defended the sun-centered system of Copernicus in De Hemelloop (the course of heaven), that appeared in 1608 as part of the Wisconstighe Ghedachtenissen. Stevin's Copernicanism met some resistance from influential Calvinist theologians, such as Ubbo Emmius, but this was uncomparable to the censoring eight years later of Galileo Galilei who shared Stevin's Copernicanism.

Stevin loved the Dutch language and was a purist. He invented many words that are still current in Dutch (a famous example is wisconst for mathematics, in modern Dutch wiskunde—literally the art of certainties; wisconstigh means mathematical). After the mid 1590s he refused to write in any other language than Dutch, which gave him a lower international profile than a man of his talents deserved.

Notes

- ↑ This is only strictly true in vacuum; when there is friction with air, lighter bodies experience theoretically a larger upward force than heavy bodies.

- ↑ George Sarton, Simon Stevin of Bruges (1548-1620), Isis, Vol. 21, p. 241 (1934), reproduces a 17th century engraving of the carriage and mentions that Hugo Grotius, the son of a friend of Stevin's and who made the trip, wrote a poem about it. However, A. J. Kox in Van Stevin tot Lorentz, Intermediair Bibliotheek, Amsterdam (1980) calls the story of the two hour trip strongly exaggerated.