User talk:Paul Wormer/scratchbook1: Difference between revisions

imported>Paul Wormer No edit summary |

imported>Paul Wormer No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''Fritz Haber''' ( | '''Fritz Haber''' (9 December 1868, [[Breslau]] – 29 January 1934, [[Basel]]) was a German chemist. He was awarded the [[Nobel Prize in Chemistry]] in 1918 for the synthesis of [[ammonia]] from the gaseous [[chemical element|elements]] [[hydrogen]] and [[nitrogen]]. [[Ammonia]] is an important feedstock for artificial fertilizers and explosives. In [[World War I]] Haber supported the use of chemical weapons and actively worked on their development. Of Jewish origin, he was forced to resign his position as director of the [[Kaiser Wilhelm Institut]] in 1933, whereupon he left Germany. He died of a heart attack on a visit to Switzerland. | ||

== Life == | == Life == | ||

Fritz Haber was born into an assimilated Jewish family. His father, Siegfried Haber, ran a business of dye pigments, paints, and pharmaceuticals. For quite a number of years he also served as alderman of Breslau (then a German city, now the Polish city of [[Wrocław]]). At Fritz's birth, serious medical complications occurred and his mother, Paula—née Haber, a first cousin of Siegfried—died three weeks later. It seemed that Fritz' father blamed the child for the mother's death. This | ===Youth and education=== | ||

Fritz Haber was born into an assimilated Jewish family. His father, Siegfried Haber, ran a business of dye pigments, paints, and pharmaceuticals. For quite a number of years he also served as alderman of Breslau (then a German city, now the Polish city of [[Wrocław]]). At Fritz's birth, serious medical complications occurred and his mother, Paula—née Haber, a first cousin of Siegfried—died three weeks later. It seemed that Fritz' father blamed the child for the mother's death. This probably was the reason that father and son never became close later in life and that tensions between them arose often. | |||

Haber attended the humanistic gymnasium St. Elizabeth in Breslau, where the curriculum contained German language and literature, Latin, Greek, mathematics and some physics, but hardly any chemistry. Fritz had a keen interest in chemistry, already as a school boy he performed chemical experiments. After finishing the gymnasium (September 29, 1886 at the age of seventeen) | Haber attended the humanistic gymnasium St. Elizabeth in Breslau, where the curriculum contained German language and literature, Latin, Greek, mathematics and some physics, but hardly any chemistry. Fritz had a keen interest in chemistry, already as a school boy he performed chemical experiments. After finishing the gymnasium (September 29, 1886 at the age of seventeen) | ||

he went to the Friedrich-Wilhelms | he went to the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität—usually referred to as the [[University of Berlin]]—to study chemistry. (This choice was against his father's wishes, who had preferred a commercial education for his son.) The director of the chemistry department of Berlin University, [[August Wilhelm von Hofmann]] close to seventy at the time, was a poor teacher and had ignored the upkeep of the chemistry lab. As a consequence Fritz Haber found his first semester in Berlin rather disappointing and he decided, as was not unusual for 19th century German students, to switch universities. He chose the [[University of Heidelberg]], where he arrived in the summer semester of 1887 and continued his studies under [[Robert Wilhelm Bunsen]]. He did his second through fourth [[semester]] in Heidelberg. From mid 1889 until mid 1890 Haber spent time in the army. | ||

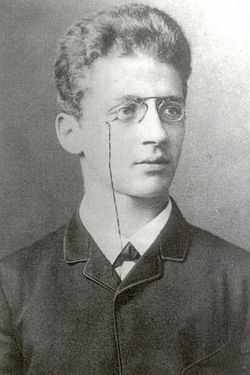

{{Image|Fritz Haber age 22.jpeg|right|250px|Fritz Haber at age 22}} | |||

In the fall of 1890 he went back to Berlin, this time to the ''Technische Hochschule'' of [[Charlottenburg]] (now the [[Technical University Berlin]]). He worked here under [[Carl Liebermann]] who had a cross appointment at Berlin University. Charlottenburg did not have the the right to grant doctorates (it received it later, in 1899). Having done his thesis work at Charlottenburg, Haber received formally his doctorate in organic chemistry at the University of Berlin (May 29, 1891) on basis of a thesis entitled ''Über einige Derivate des Piperonal'' (About some derivatives of [[Piperonal]]). | |||

After completion of his university studies, Fritz's father, who had not given up his hope that his son would become a business man, insisted that he do a few apprenticeships in chemical industry. Although Fritz Haber acquired a taste for chemical engineering during these apprenticeships, they also bored him and he convinced his father that he should return to academia to advance his technical knowledge. His father agreed that he spend a semester with [[Georg Lunge]], professor of chemical technology and a distant relative of the Habers, at the [[Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich|Institute of Technology]] in [[Zurich]]. After that he worked for six months in his father's business, which finally made Haber senior realize that his son's talent was not in commerce. | |||

So finally his father agreed that he take up a scientific career and Fritz went to work with [[Ludwig Knorr]] at the [[University of Jena]], publishing with him one paper.<ref>Ludwig Knorr and Fritz Haber, ''Ueber die Konstitution des Diacetbernsteinsäureesters'' (On the constitution of diaceto amber acid ester), Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft | |||

Vol. '''27''', pp. 1151 – 1167</ref> . In Jena in 1893, Haber converted to the [[Protestantism|Protestant]]-Christian faith, against his father's wishes. | Vol. '''27''', pp. 1151 – 1167</ref> . In Jena in 1893, Haber converted to the [[Protestantism|Protestant]]-Christian faith, against his father's wishes. | ||

===Karslruhe=== | |||

After one and a half year in Jena, still uncertain whether to devote himself to chemical engineering or physical chemistry, Haber traveled in the spring of 1894 to the [[Technical University of Karlsruhe]], without being certain of a position there. After having worked for several months in Karlsruhe as an unpaid assistant, the professor of Chemical Technology, [[Hans Bunte]], put him on the payroll (on December 16, 1894). Two years later Haber made his ''Habilitation'' with a dissertation entitled ''Experimentelle Untersuchungen über Zersetzung und Verbrennung von Kohlenwasserstoffen'' (Experimental Studies on the Decomposition and Combustion of Hydrocarbons) (1896) and Haber received the title ''Privat-Dozent''. Bunte was especially interested in combustion chemistry and [[Carl Engler]], who was also in Karlsruhe, introduced Haber to the study of petroleum. Haber's subsequent work was greatly influenced by Bunte and Engler and he always spoke of them with great respect. In 1898, Haber published the textbook ''Grundriss der Technischen Elektrochemie'' (Fundamentals of technical electrochemistry) and obtained the honorary title of ''außerordentliche'' (extraordinary) professor in technical electrochemistry. From 1904 on Haber worked on the catalytic formation of ammonia. In 1905 he published his book ''Thermodynamik technischer Gasreaktionen'' (Thermodynamics of technical gas reactions), which treats the foundations of his subsequent thermochemical work. In 1906 he succeeded [[Max Julius Le Blanc]] to the chair of Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry. Le Blanc left because he obtained the prestigious chair in Leipzig held previously by [[Wilhelm Ostwald]]. | |||

In 1901, Haber married Clara Immerwahr, daughter of respected Jewish family in Breslau, whom he had known as a teenager. Clara, who also had converted to the protestant religion, matched Fritz in ambition and determination, having fought against prejudice and opposition to become the first woman to obtain a doctorate in science at Breslau University. She committed suicide the night of May 1, 1915, shooting herself with Fritz’s army pistol, supposedly after heated arguments over Fritz’s involvement with the poison gas campaign. | |||

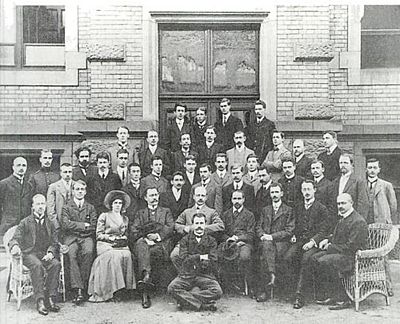

{{Image|Friz Haber group 1909.jpg|left|400px|Research group of Fritz Haber in Karlsruhe (1909). Fritz Haber sits in the middle (5th from the left) just above man sitting on the ground.}} | |||

Haber remained in Karlsruhe until 1911 and made a great reputation for himself during those years, especially in electrochemistry and chemical thermodynamics. He built a very large research group of about forty persons (including research students). His most important work during these years concerned the fixation of nitrogen from the air. | |||

<!-- | <!-- | ||

Revision as of 04:45, 2 March 2010

Fritz Haber (9 December 1868, Breslau – 29 January 1934, Basel) was a German chemist. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1918 for the synthesis of ammonia from the gaseous elements hydrogen and nitrogen. Ammonia is an important feedstock for artificial fertilizers and explosives. In World War I Haber supported the use of chemical weapons and actively worked on their development. Of Jewish origin, he was forced to resign his position as director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institut in 1933, whereupon he left Germany. He died of a heart attack on a visit to Switzerland.

Life

Youth and education

Fritz Haber was born into an assimilated Jewish family. His father, Siegfried Haber, ran a business of dye pigments, paints, and pharmaceuticals. For quite a number of years he also served as alderman of Breslau (then a German city, now the Polish city of Wrocław). At Fritz's birth, serious medical complications occurred and his mother, Paula—née Haber, a first cousin of Siegfried—died three weeks later. It seemed that Fritz' father blamed the child for the mother's death. This probably was the reason that father and son never became close later in life and that tensions between them arose often.

Haber attended the humanistic gymnasium St. Elizabeth in Breslau, where the curriculum contained German language and literature, Latin, Greek, mathematics and some physics, but hardly any chemistry. Fritz had a keen interest in chemistry, already as a school boy he performed chemical experiments. After finishing the gymnasium (September 29, 1886 at the age of seventeen) he went to the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität—usually referred to as the University of Berlin—to study chemistry. (This choice was against his father's wishes, who had preferred a commercial education for his son.) The director of the chemistry department of Berlin University, August Wilhelm von Hofmann close to seventy at the time, was a poor teacher and had ignored the upkeep of the chemistry lab. As a consequence Fritz Haber found his first semester in Berlin rather disappointing and he decided, as was not unusual for 19th century German students, to switch universities. He chose the University of Heidelberg, where he arrived in the summer semester of 1887 and continued his studies under Robert Wilhelm Bunsen. He did his second through fourth semester in Heidelberg. From mid 1889 until mid 1890 Haber spent time in the army.

In the fall of 1890 he went back to Berlin, this time to the Technische Hochschule of Charlottenburg (now the Technical University Berlin). He worked here under Carl Liebermann who had a cross appointment at Berlin University. Charlottenburg did not have the the right to grant doctorates (it received it later, in 1899). Having done his thesis work at Charlottenburg, Haber received formally his doctorate in organic chemistry at the University of Berlin (May 29, 1891) on basis of a thesis entitled Über einige Derivate des Piperonal (About some derivatives of Piperonal).

After completion of his university studies, Fritz's father, who had not given up his hope that his son would become a business man, insisted that he do a few apprenticeships in chemical industry. Although Fritz Haber acquired a taste for chemical engineering during these apprenticeships, they also bored him and he convinced his father that he should return to academia to advance his technical knowledge. His father agreed that he spend a semester with Georg Lunge, professor of chemical technology and a distant relative of the Habers, at the Institute of Technology in Zurich. After that he worked for six months in his father's business, which finally made Haber senior realize that his son's talent was not in commerce.

So finally his father agreed that he take up a scientific career and Fritz went to work with Ludwig Knorr at the University of Jena, publishing with him one paper.[1] . In Jena in 1893, Haber converted to the Protestant-Christian faith, against his father's wishes.

Karslruhe

After one and a half year in Jena, still uncertain whether to devote himself to chemical engineering or physical chemistry, Haber traveled in the spring of 1894 to the Technical University of Karlsruhe, without being certain of a position there. After having worked for several months in Karlsruhe as an unpaid assistant, the professor of Chemical Technology, Hans Bunte, put him on the payroll (on December 16, 1894). Two years later Haber made his Habilitation with a dissertation entitled Experimentelle Untersuchungen über Zersetzung und Verbrennung von Kohlenwasserstoffen (Experimental Studies on the Decomposition and Combustion of Hydrocarbons) (1896) and Haber received the title Privat-Dozent. Bunte was especially interested in combustion chemistry and Carl Engler, who was also in Karlsruhe, introduced Haber to the study of petroleum. Haber's subsequent work was greatly influenced by Bunte and Engler and he always spoke of them with great respect. In 1898, Haber published the textbook Grundriss der Technischen Elektrochemie (Fundamentals of technical electrochemistry) and obtained the honorary title of außerordentliche (extraordinary) professor in technical electrochemistry. From 1904 on Haber worked on the catalytic formation of ammonia. In 1905 he published his book Thermodynamik technischer Gasreaktionen (Thermodynamics of technical gas reactions), which treats the foundations of his subsequent thermochemical work. In 1906 he succeeded Max Julius Le Blanc to the chair of Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry. Le Blanc left because he obtained the prestigious chair in Leipzig held previously by Wilhelm Ostwald.

In 1901, Haber married Clara Immerwahr, daughter of respected Jewish family in Breslau, whom he had known as a teenager. Clara, who also had converted to the protestant religion, matched Fritz in ambition and determination, having fought against prejudice and opposition to become the first woman to obtain a doctorate in science at Breslau University. She committed suicide the night of May 1, 1915, shooting herself with Fritz’s army pistol, supposedly after heated arguments over Fritz’s involvement with the poison gas campaign.

Haber remained in Karlsruhe until 1911 and made a great reputation for himself during those years, especially in electrochemistry and chemical thermodynamics. He built a very large research group of about forty persons (including research students). His most important work during these years concerned the fixation of nitrogen from the air.

- ↑ Ludwig Knorr and Fritz Haber, Ueber die Konstitution des Diacetbernsteinsäureesters (On the constitution of diaceto amber acid ester), Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft Vol. 27, pp. 1151 – 1167