Vibrio fischeri: Difference between revisions

imported>Yeong M Shin No edit summary |

imported>Yeong M Shin No edit summary |

||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

==Bioluminescence== | ==Bioluminescence== | ||

Bioluminescence, the ability of living organisms to produce light has evolved independently multiple times and occurs in a variety of marine species as well as some terrestrial forms | Bioluminescence, the ability of living organisms to produce light has evolved independently multiple times and occurs in a variety of marine species as well as some terrestrial forms. There are various mechanisms leading to light production and different forms of luciferin and luciferase are used but they all require the use of molecular oxygen <ref>Widder, E. A. "Marine Bioluminescence." Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution. <http://gupea.ub.gu.se/dspace/bitstream/2077/19437/5/gupea_2077_19437_5.pdf> (created 2001; accessed 03/28/09)</ref>. In the bacterial bioluminescent pathway, luciferase catalyses the dual oxidation of luciferin, a reduced riboflavin mononucleotide (FMNH<sub>2</sub>) and an associated molecule, a long chain aldehyde. ATP is required to catalyze this reaction and the resulting products are light, water, oxyluciferin and carboxyl group<ref>Ruby, E. G., McFall-Ngai, M. J. Oxygen-utilizing reactions and symbiotic colonization of the squid light organ by Vibrio fischeri. Trends in microbiology. 415 Volume 7, issue , 10 October 1999, Pages 414-420. Accessed from ScienceDirect.</ref>. Bacterial luciferase is also required for aerobic respiration and luciferase has a high affinity for molecular oxygen. It is hypothesized that bacterial luciferase evolved from an enzyme whose original function was to provide protection from reactive oxygen species (ROS) in a dark pathway. Wild type bioluminescent bacteria survive UV radiation and hydrogen peroxide better than lux mutants. | ||

{{Image|juvenile_squid1a.jpg|left|250px|Juvenile ''E. scolopes'', symbiotic host of ''V. fischeri''}} | {{Image|juvenile_squid1a.jpg|left|250px|Juvenile ''E. scolopes'', symbiotic host of ''V. fischeri''}} | ||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

==Ecology== | ==Ecology== | ||

''V. fischeri'' can be located in the microhabitats of its hosts’ light organs, but can also be found living freely as ‘marine snow’, in fecal pellets, as saprohytes (Herring, Bioluminescence), and amongst the microbial flora in the guts of marine animals. The bacterium is distributed in the pelagic zone of temperate and subtropical waters | ''V. fischeri'' can be located in the microhabitats of its hosts’ light organs, but can also be found living freely as ‘marine snow’, in fecal pellets, as saprohytes (Herring, Bioluminescence), and amongst the microbial flora in the guts of marine animals. The bacterium is distributed in the pelagic zone of temperate and subtropical waters <ref>Ruby, E. G., McFall-Ngai, M. J. Oxygen-utilizing reactions and symbiotic colonization of the squid light organ by Vibrio fischeri. Trends in microbiology. 415 Volume 7, issue , 10 October 1999, Pages 414-420. Accessed from ScienceDirect</ref>. However, higher cell populations of ''V. fischeri'' is achieved when it is associated with its host. | ||

===Symbiosis=== | ===Symbiosis=== | ||

The symbiosis benefits ''E.scolopes'' by using the bioluminescent bacteria in a camouflage strategy called ‘counter-illumination’. The light produced by the bacterium is projected ventrally by the squid, which mimics down dwelling moonlight when viewed from below. The squid effectively projects no shadow, and it can regulate the amount of bacterial illumination with the light organ | The symbiosis benefits ''E.scolopes'' by using the bioluminescent bacteria in a camouflage strategy called ‘counter-illumination’. The light produced by the bacterium is projected ventrally by the squid, which mimics down dwelling moonlight when viewed from below. The squid effectively projects no shadow, and it can regulate the amount of bacterial illumination with the light organ <ref>Ruby, E. G., McFall-Ngai, M. J. Oxygen-utilizing reactions and symbiotic colonization of the squid light organ by Vibrio fischeri. Trends in microbiology. 415 Volume 7, issue , 10 October 1999, Pages 414-420. Accessed from ScienceDirect</ref>. The squid provides housing and nutrients, especially carbon and nitrogen, in the form of proteins and peptides inside the crypts of the light organ <ref>Koropatnick, T. Squid-vibrio symbiosis. Microbial life. Science education resource center at Carleton college. <http://serc.carleton.edu/microbelife/topics/marinesymbiosis/squid-vibrio/index.html> (updated 11/2006; accessed 03/28/09)</ref>. In providing a nutrient rich environment, the bacteria population increases to 1.0<sup>9</sup> cells of which 90-95% are expelled every morning by the squid. The remaining bacteria in the light organ are replenished daily, and the squid becomes a vehicle to produce an abundance of ''V. fischeri'' <ref>Ruby, E. G., McFall-Ngai, M. J. Oxygen-utilizing reactions and symbiotic colonization of the squid light organ by Vibrio fischeri. Trends in microbiology. 415 Volume 7, issue , 10 October 1999, Pages 414-420. Accessed from ScienceDirect</ref>. | ||

The symbiotic relationship between strains of ''V. fischeri'' and their particular hosts is highly specific | The symbiotic relationship between strains of ''V. fischeri'' and their particular hosts is highly specific <>ref>McFall-Ngai, M. J. 2000. Negotiations between animals and bacteria: the 'diplomacy' of the squid-vibrio symbiosis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. Mol. Integr. Physiol., 126(4), 471-480</ref>. Newly hatched squids are born without the bacterium and must acquire them from the surrounding seawaters. In waters inhabited by ''E.scolopes'', the abundance of ''V. fischeri'' constitutes only 0.1% of total microbes per mL of seawater, yet only the specific strain of ''V. fischeri'' can effectively colonize and remain in the light organ of the squid. The bacterium is housed inside the crypts of the light organ located in the squid’s mantle cavity. Once the bacterium is acquired and colonizes the crypts, morphogenesis occurs for both the bacterium and its host. The bacteria lose the flagella, and the cells decrease in size. As for the host, the ciliated fields used to obtain the bacterium undergo programmed cell death, and the light organ swells<ref>McFall-Ngai, M. J. 2000. Negotiations between animals and bacteria: the 'diplomacy' of the squid-vibrio symbiosis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. Mol. Integr. Physiol., 126(4), 471-480.</ref> Colonization by the bacterium concurrently alters gene expression in the squid and the bacterium. | ||

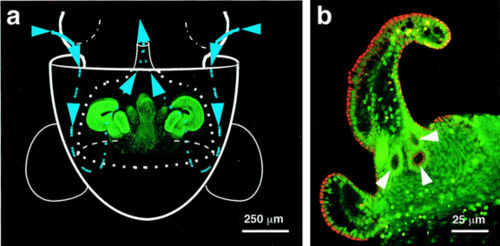

{{Image|JuvScolopesDiagram.jpg|center|500px|Inoculation pathway of ''V. fischeri'' into light organ of juvenile ''E. scolopes''}} | {{Image|JuvScolopesDiagram.jpg|center|500px|Inoculation pathway of ''V. fischeri'' into light organ of juvenile ''E. scolopes''}} | ||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

To date, the complete genomes of two strains of ''V. fischeri'', ES114 and MJII have been sequenced. Strain ES114 isolated from ''E.scolopes'' contains two circular chromosomes and a circular plasmid pES100. The genetic material is composed of DNA and the total genome is 4.284 Mbp in length. Chromosome 1, the larger of the two chromosomes contains 2586 genes, while Chromosome 2 and the plasmid contains 1175 and 57 genes respectively. | To date, the complete genomes of two strains of ''V. fischeri'', ES114 and MJII have been sequenced. Strain ES114 isolated from ''E.scolopes'' contains two circular chromosomes and a circular plasmid pES100. The genetic material is composed of DNA and the total genome is 4.284 Mbp in length. Chromosome 1, the larger of the two chromosomes contains 2586 genes, while Chromosome 2 and the plasmid contains 1175 and 57 genes respectively. | ||

The lux operon system, located on chromosome 2, contains luxI, luxR and luxCDABEG. LuxI encodes for AHL synthase, the enzyme that produces the autoinducer AHL. The Lux R gene produces the AHL dependent transcriptional activator protein that binds to the AHL and promotes the transcription of the lux operon. Luciferase, the enzyme responsible for catalyzing the light reaction, is encoded by luxA and lux B. LuxA produces the alpha chain subunit and luxB, the beta subunit of luciferase. LuxCDE are required for aldehyde synthesis ( | The lux operon system, located on chromosome 2, contains luxI, luxR and luxCDABEG. LuxI encodes for AHL synthase, the enzyme that produces the autoinducer AHL. The Lux R gene produces the AHL dependent transcriptional activator protein that binds to the AHL and promotes the transcription of the lux operon. Luciferase, the enzyme responsible for catalyzing the light reaction, is encoded by luxA and lux B. LuxA produces the alpha chain subunit and luxB, the beta subunit of luciferase. LuxCDE are required for aldehyde synthesis (BioUK). LuxG encodes flavin mononucleotide reductase<ref>NCBI. Entrez genome project. <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?Db=genomeprj&Cmd=Retrieve&list_uids=12986>(updated 2/09;accessed 03/29/09) | ||

</ref>. | |||

==Pathology== | ==Pathology== | ||

''V. fischeri'' is non-pathogenic to humans but | ''V. fischeri'' is non-pathogenic to humans but is pathogenic to some marine invertebrates. Within the Vibrios family there are three human pathogens ''V. cholerae'', ''V.parahaemolytus'', ''V. vulnificus''. | ||

==Application to Biotechnology== | ==Application to Biotechnology== | ||

| Line 67: | Line 68: | ||

Ruby, E. G., M. Urbanowski, J. Campbell, A. Dunn, M. Faini, R. Gunsalus, P. Lostroh, C. Lupp, J. McCann, D. Millikan, A. Schaefer, E. Stabb, A. Stevens, K. Visick, C. Whistler, and E. P. Greenberg. 2005. Complete genome sequence of Vibrio fischeri: a symbiotic bacterium with pathogenic congeners. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:3004-3009 | Ruby, E. G., M. Urbanowski, J. Campbell, A. Dunn, M. Faini, R. Gunsalus, P. Lostroh, C. Lupp, J. McCann, D. Millikan, A. Schaefer, E. Stabb, A. Stevens, K. Visick, C. Whistler, and E. P. Greenberg. 2005. Complete genome sequence of Vibrio fischeri: a symbiotic bacterium with pathogenic congeners. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:3004-3009 | ||

Ruby, E. G., McFall-Ngai, M. J. Oxygen-utilizing reactions and symbiotic colonization of the squid light organ by Vibrio fischeri. Trends in microbiology. 415 Volume 7, issue | Ruby, E. G., McFall-Ngai, M. J. Oxygen-utilizing reactions and symbiotic colonization of the squid light organ by Vibrio fischeri. Trends in microbiology. 415 Volume 7, issue , 10October 1999, Pages 414-420. Accessed from ScienceDirect | ||

Thompson, F.L., Austin, B., Swings, J. The biology of Vibrios. 2006. ASM press. Virginia. | Thompson, F.L., Austin, B., Swings, J. The biology of Vibrios. 2006. ASM press. Virginia. | ||

Revision as of 21:16, 24 April 2009

For the course duration, the article is closed to outside editing. Of course you can always leave comments on the discussion page. The anticipated date of course completion is May 21, 2009. One month after that date at the latest, this notice shall be removed. Besides, many other Citizendium articles welcome your collaboration! |

| Vibrio fischeri | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Binomial name | ||||||||||||||

| Vibrio fischeri |

Description and significance

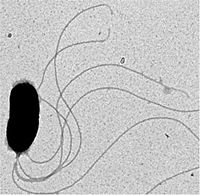

Vibrio fischeri is a gram-negative marine bioluminescent bacterium that forms symbiosis with various species of fish and squid.[1] V. fischeri is a member of the Vibrionacea family of marine γ-proteobacteria which includes many species having symbiotic and pathogenic relationships with animals.[2] The bioluminescent bacteria chemically produces light in a reaction where a substrate molecule, luciferin is oxidized by an enzyme, luciferase. This process emits light energy rather than heat energy.[3] The proteins necessary for the production of bioluminescence are encoded in a set of genes called the lux operon. The expression of the lux operon and other genes depend upon the presence of a signal molecule known as N-acyl homoserine lactone (AHL). The accumulation of the AHL is a function of population density and hence, bioluminescence can only occur after the bacterium reaches a critical population threshold. The expression of genes through the interaction of bacteria through a signal molecule is known as quorum sensing.[4] Intercellular communication via signal molecules has been shown to regulate genes whose products are needed for establishment of virulence, symbiosis, biofilm formation, plasmid transfer and morphogenesis in a variety of microorganisms.[5] Prior to its discovery in V. fischeri, quorum sensing and other mechanisms for bacterial cell communication was unknown. The particular symbiosis between a strain of V. fischeri and its host, the Hawian bobtail squid Euprmma scolopes, has been studied extensively. Comparative studies between symbiotic species, like V. fischeri, and human pathogenic species, like Vibrio cholerae, are being examined to elucidate the mechanisms for pathogenesis and pathogenic/host relationships.[6]

Bioluminescence

Bioluminescence, the ability of living organisms to produce light has evolved independently multiple times and occurs in a variety of marine species as well as some terrestrial forms. There are various mechanisms leading to light production and different forms of luciferin and luciferase are used but they all require the use of molecular oxygen [7]. In the bacterial bioluminescent pathway, luciferase catalyses the dual oxidation of luciferin, a reduced riboflavin mononucleotide (FMNH2) and an associated molecule, a long chain aldehyde. ATP is required to catalyze this reaction and the resulting products are light, water, oxyluciferin and carboxyl group[8]. Bacterial luciferase is also required for aerobic respiration and luciferase has a high affinity for molecular oxygen. It is hypothesized that bacterial luciferase evolved from an enzyme whose original function was to provide protection from reactive oxygen species (ROS) in a dark pathway. Wild type bioluminescent bacteria survive UV radiation and hydrogen peroxide better than lux mutants.

Ecology

V. fischeri can be located in the microhabitats of its hosts’ light organs, but can also be found living freely as ‘marine snow’, in fecal pellets, as saprohytes (Herring, Bioluminescence), and amongst the microbial flora in the guts of marine animals. The bacterium is distributed in the pelagic zone of temperate and subtropical waters [9]. However, higher cell populations of V. fischeri is achieved when it is associated with its host.

Symbiosis

The symbiosis benefits E.scolopes by using the bioluminescent bacteria in a camouflage strategy called ‘counter-illumination’. The light produced by the bacterium is projected ventrally by the squid, which mimics down dwelling moonlight when viewed from below. The squid effectively projects no shadow, and it can regulate the amount of bacterial illumination with the light organ [10]. The squid provides housing and nutrients, especially carbon and nitrogen, in the form of proteins and peptides inside the crypts of the light organ [11]. In providing a nutrient rich environment, the bacteria population increases to 1.09 cells of which 90-95% are expelled every morning by the squid. The remaining bacteria in the light organ are replenished daily, and the squid becomes a vehicle to produce an abundance of V. fischeri [12]. The symbiotic relationship between strains of V. fischeri and their particular hosts is highly specific <>ref>McFall-Ngai, M. J. 2000. Negotiations between animals and bacteria: the 'diplomacy' of the squid-vibrio symbiosis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. Mol. Integr. Physiol., 126(4), 471-480</ref>. Newly hatched squids are born without the bacterium and must acquire them from the surrounding seawaters. In waters inhabited by E.scolopes, the abundance of V. fischeri constitutes only 0.1% of total microbes per mL of seawater, yet only the specific strain of V. fischeri can effectively colonize and remain in the light organ of the squid. The bacterium is housed inside the crypts of the light organ located in the squid’s mantle cavity. Once the bacterium is acquired and colonizes the crypts, morphogenesis occurs for both the bacterium and its host. The bacteria lose the flagella, and the cells decrease in size. As for the host, the ciliated fields used to obtain the bacterium undergo programmed cell death, and the light organ swells[13] Colonization by the bacterium concurrently alters gene expression in the squid and the bacterium.

Genome

To date, the complete genomes of two strains of V. fischeri, ES114 and MJII have been sequenced. Strain ES114 isolated from E.scolopes contains two circular chromosomes and a circular plasmid pES100. The genetic material is composed of DNA and the total genome is 4.284 Mbp in length. Chromosome 1, the larger of the two chromosomes contains 2586 genes, while Chromosome 2 and the plasmid contains 1175 and 57 genes respectively. The lux operon system, located on chromosome 2, contains luxI, luxR and luxCDABEG. LuxI encodes for AHL synthase, the enzyme that produces the autoinducer AHL. The Lux R gene produces the AHL dependent transcriptional activator protein that binds to the AHL and promotes the transcription of the lux operon. Luciferase, the enzyme responsible for catalyzing the light reaction, is encoded by luxA and lux B. LuxA produces the alpha chain subunit and luxB, the beta subunit of luciferase. LuxCDE are required for aldehyde synthesis (BioUK). LuxG encodes flavin mononucleotide reductase[14].

Pathology

V. fischeri is non-pathogenic to humans but is pathogenic to some marine invertebrates. Within the Vibrios family there are three human pathogens V. cholerae, V.parahaemolytus, V. vulnificus.

Application to Biotechnology

Current Research

References

- ↑ Ruby, E. G., McFall-Ngai, M. J. Oxygen-utilizing reactions and symbiotic colonization of the squid light organ by Vibrio fischeri. Trends in microbiology. 415 Volume 7, issue 10, October 1999, Pages 414-420. Accessed from ScienceDirect.

- ↑ Ruby, E. G., M. Urbanowski, J. Campbell, A. Dunn, M. Faini, R. Gunsalus, P. Lostroh, C. Lupp, J. McCann, D. Millikan, A. Schaefer, E. Stabb, A. Stevens, K. Visick, C. Whistler, and E. P. Greenberg. 2005. Complete genome sequence of Vibrio fischeri: a symbiotic bacterium with pathogenic congeners. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:3004-3009

- ↑ Herring, P.J. and Widder, E.A.2001. Bioluminescence in Plankton and Nekton. In: Steele, J.H., Thorpe, S.A. and Turekian, K.K. editors, Encyclopedia of Ocean Science, Vol. 1, 308-317. Academic Press, San Diego. Accessed from "International society of bioluminescence and chemiluminescence", <http://www.isbc.unibo.it/Files/BC_PlanktonNekton.htm> (updated 10/2009; accessed 03/20/09)

- ↑ NCBI. Entrez genome project. <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?Db=genomeprj&Cmd=Retrieve&list_uids=12986>(updated 2/09;accessed 03/29/09)

- ↑ Willey, J.M., Sherwood, L.M., Woolverton, C. J. Prescott, Harley, and Klein's Microbiology. 7th Ed. 2008. McGraw-Hill. New York.

- ↑ Ruby, E. G., M. Urbanowski, J. Campbell, A. Dunn, M. Faini, R. Gunsalus, P. Lostroh, C. Lupp, J. McCann, D. Millikan, A. Schaefer, E. Stabb, A. Stevens, K. Visick, C. Whistler, and E. P. Greenberg. 2005. Complete genome sequence of Vibrio fischeri: a symbiotic bacterium with pathogenic congeners. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:3004-3009

- ↑ Widder, E. A. "Marine Bioluminescence." Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution. <http://gupea.ub.gu.se/dspace/bitstream/2077/19437/5/gupea_2077_19437_5.pdf> (created 2001; accessed 03/28/09)

- ↑ Ruby, E. G., McFall-Ngai, M. J. Oxygen-utilizing reactions and symbiotic colonization of the squid light organ by Vibrio fischeri. Trends in microbiology. 415 Volume 7, issue , 10 October 1999, Pages 414-420. Accessed from ScienceDirect.

- ↑ Ruby, E. G., McFall-Ngai, M. J. Oxygen-utilizing reactions and symbiotic colonization of the squid light organ by Vibrio fischeri. Trends in microbiology. 415 Volume 7, issue , 10 October 1999, Pages 414-420. Accessed from ScienceDirect

- ↑ Ruby, E. G., McFall-Ngai, M. J. Oxygen-utilizing reactions and symbiotic colonization of the squid light organ by Vibrio fischeri. Trends in microbiology. 415 Volume 7, issue , 10 October 1999, Pages 414-420. Accessed from ScienceDirect

- ↑ Koropatnick, T. Squid-vibrio symbiosis. Microbial life. Science education resource center at Carleton college. <http://serc.carleton.edu/microbelife/topics/marinesymbiosis/squid-vibrio/index.html> (updated 11/2006; accessed 03/28/09)

- ↑ Ruby, E. G., McFall-Ngai, M. J. Oxygen-utilizing reactions and symbiotic colonization of the squid light organ by Vibrio fischeri. Trends in microbiology. 415 Volume 7, issue , 10 October 1999, Pages 414-420. Accessed from ScienceDirect

- ↑ McFall-Ngai, M. J. 2000. Negotiations between animals and bacteria: the 'diplomacy' of the squid-vibrio symbiosis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. Mol. Integr. Physiol., 126(4), 471-480.

- ↑ NCBI. Entrez genome project. <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?Db=genomeprj&Cmd=Retrieve&list_uids=12986>(updated 2/09;accessed 03/29/09)

Fuqua,C., Winans,S., Greenberg, P. Census and consensus in bacterial ecosystems: the luxR-luxI family of quorum-sensing transciptional regulators. Annual Review of Microbiology Vol. 50: 727-751 (Volume publication date October 1996) (doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.727)

Herring, P.J. and Widder, E.A.2001. Bioluminescence in Plankton and Nekton. In: Steele, J.H., Thorpe, S.A. and Turekian, K.K. editors, Encyclopedia of Ocean Science, Vol. 1, 308-317. Academic Press, San Diego. Accessed from "International society of bioluminescence and chemiluminescence", <http://www.isbc.unibo.it/Files/BC_PlanktonNekton.htm> (updated 10/2009; accessed 03/20/09)

McFall-Ngai, M. J. 2000. Negotiations between animals and bacteria: the 'diplomacy' of the squid-vibrio symbiosis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. Mol. Integr. Physiol., 126(4), 471-480.

NCBI. Entrez genome project. <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?Db=genomeprj&Cmd=Retrieve&list_uids=12986>(updated 2/09;accessed 03/29/09)

Ruby, E. G., M. Urbanowski, J. Campbell, A. Dunn, M. Faini, R. Gunsalus, P. Lostroh, C. Lupp, J. McCann, D. Millikan, A. Schaefer, E. Stabb, A. Stevens, K. Visick, C. Whistler, and E. P. Greenberg. 2005. Complete genome sequence of Vibrio fischeri: a symbiotic bacterium with pathogenic congeners. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:3004-3009

Ruby, E. G., McFall-Ngai, M. J. Oxygen-utilizing reactions and symbiotic colonization of the squid light organ by Vibrio fischeri. Trends in microbiology. 415 Volume 7, issue , 10October 1999, Pages 414-420. Accessed from ScienceDirect

Thompson, F.L., Austin, B., Swings, J. The biology of Vibrios. 2006. ASM press. Virginia.

Visick, K., Ruby, E. G. Vibrio fischeri and its host: it takes two to tango. Current Opinion in Microbiology. Volume 9, Issue 6, December 2006, Pages 632-638. Accessed from ScienceDirect.

Willey, J.M., Sherwood, L.M., Woolverton, C. J. Prescott, Harley, and Klein's Microbiology. 7th Ed. 2008. McGraw-Hill. New York.

Web resource

Graf, J. Light-organ symbiosis of V. fischeri and the Hawaiian squid, Euprymna scolopes. Bacteria-animal symbiosis site: Graf lab. University of Connecticut. <http://web.uconn.edu/mcbstaff/graf/VfEs/VfEssym.htm>(created 2007; accessed 03/20/09)

Haddock, S.H.D.; McDougall, C.M.; Case, J.F. "The Bioluminescence Web Page", <http://lifesci.ucsb.edu/~biolum/> (created 1997; updated 2009; accessed 03/20/09).

Koropatnick, T. Squid-vibrio symbiosis. Microbial life. Science education resource center at Carleton college. <http://serc.carleton.edu/microbelife/topics/marinesymbiosis/squid-vibrio/index.html> (updated 11/2006; accessed 03/28/09)

Widder, E. A. "Marine Bioluminescence." Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution. <http://gupea.ub.gu.se/dspace/bitstream/2077/19437/5/gupea_2077_19437_5.pdf> (created 2001; accessed 03/28/09)