Quadratic equation: Difference between revisions

imported>Michael Underwood No edit summary |

imported>Michael Underwood No edit summary |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

==Three possibilities== | ==Three possibilities== | ||

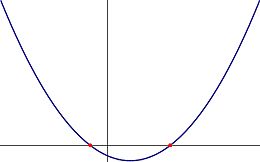

[[Image:parabola_two_real_roots.jpg|thumb|260px|Figure 1: A parabola with two real roots. This corresponds to a second-degree (real) polynomial with a positive discriminant.]] | |||

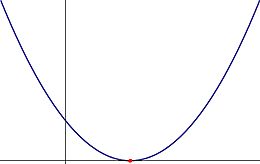

[[Image:Parabola_one_real_root.jpg|thumb|260px|Figure 2: A parabola with two only one real root, but of multiplicity 2. This corresponds to a second-degree (real) polynomial with a discriminant equal to zero.]] | |||

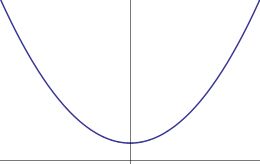

[[Image:Parabola_no_real_roots.jpg|thumb|260px|Figure 3: A parabola with no real roots, as seen by the fact that it does not intersect the horizontal axis. This corresponds to a second-degree (real) polynomial with a negative discriminant.]] | |||

===<math>\Delta>0</math>=== | ===<math>\Delta>0</math>=== | ||

Here we have two distinct real roots, since the square root of <math>\Delta</math> will also be real and greater than zero, meaning that we have | Here we have two distinct real roots, since the square root of <math>\Delta</math> will also be real and greater than zero, meaning that we have | ||

Revision as of 16:20, 12 October 2007

The quadratic equation is a formula for finding the roots of a second-degree polynomial. Any second-degree polynomial in the variable will be of the form

where , , and are real constants and is not zero (if it was, the polynomial would only be first-degree). In general the constant coefficients , , and and the variable can be complex, however the quadratic equation is most frequently applied and learnt in the case of real coefficients and a real variable. This corresponds to a parabola, and the roots are then the values of at which the parabola crosses the -axis.

This means that the roots of the polynomial are the particular values of for which the polynomial equals zero. The Fundamental Theorem of Algebra tells us that we should expect there to be two roots for a second-degree polynomial, although they might be equal in some cases, and might not even be real even when the coefficients and variable are. If we call the roots and then what we are saying is that

This is where the quadratic equation comes in. It tells us that the solutions and can always be found from the equation

Looking at the above result it is clear that the quantity (called the discriminant) is of interest, for two reasons. First it is part of the quantity that is either plus or minus depending on whether you are looking at the root or . Second it is under a square root, so we must wonder what happens when it is negative. This gives us three cases to look at.

Three possibilities

Here we have two distinct real roots, since the square root of will also be real and greater than zero, meaning that we have

and

These can be seen graphically as the two red dots in Figure 1. In this case we can rewrite the polynomial in terms of its roots as

Now there is only one distinct root. It is still real, and is said to have a multiplicity of 2. This is because the root is given by

and the polynomial can be expressed as

This case occurs when the parabola described by the polynomial just touches the -axis at exactly one point, the red dot shown in Figure 2.

For negative values of the discriminant there are no real roots to the polynomial. Graphically this corresponds to the situation where the lowest point on the parabola is above the -axis (or the highest point is below it, if is negative) as shown in Figure 3. In this case the roots still exist, as guaranteed by the fundamental theorem of algebra, but they are complex so cannot be shown on the real number line.

Proof

The simplest way to show that the values are in fact roots to the polynomial above is to substitute them into the equation

as desired. Notice that this proof is valid even in the case where is less than zero.