Second Bank of the United States: Difference between revisions

imported>Russell D. Jones m (→Panic of 1819: spelling) |

imported>Gareth Leng (→Bibliography: subpage) |

||

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

The Greek Revival style used for the Second Bank contrasts slightly with the earlier, Federal style in architecture used for the First Bank, whose building also still stands and is located nearby in Philadelphia. This can be seen in the more Roman-influenced Federal structure's ornate, colossal Corinthian columns of its façade, which is also embellished by Corinthian pilasters and a symmetric arrangement of sash windows piercing the two stories of the façade. The roofline is also topped by a balustrade and the heavy modillions adorning the pediment give the First Bank an appearance much more like a Roman villa than a Greek temple. | The Greek Revival style used for the Second Bank contrasts slightly with the earlier, Federal style in architecture used for the First Bank, whose building also still stands and is located nearby in Philadelphia. This can be seen in the more Roman-influenced Federal structure's ornate, colossal Corinthian columns of its façade, which is also embellished by Corinthian pilasters and a symmetric arrangement of sash windows piercing the two stories of the façade. The roofline is also topped by a balustrade and the heavy modillions adorning the pediment give the First Bank an appearance much more like a Roman villa than a Greek temple. | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

Revision as of 07:05, 12 February 2009

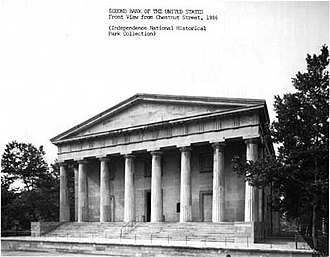

The Second Bank of the United States was a privately owned bank chartered by Congress in 1816, five years after the expiration of the First Bank of the United States. It was founded during the administration of James Madison who realized the need for a strong national bank when he tried to finance the War of 1812 without one. The Bank was headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, with branches in most major cities. The headquarters building, designed by the architect William Strickland, still stands as part of Independence National Historical Park.

The Bank served as the depository for Federal funds until 1833, when President Andrew Jackson instructed his Secretaries of the Treasury to cease depositing the funds. Two refused to obey, so he fired them, one after the other, until he got one who obeyed: Roger B. Taney. The Bank, always a privately owned institution, lost its Federal charter in 1836. It became defunct in 1841.

Founding

This Second bank was patterned after the First Bank of the United States. The legality of the Bank was upheld in the U.S. Supreme Court case McCulloch v. Maryland 17 U.S. 316 (1819) that also declared null and void any state law contrary to a federal law made in pursuance of the Constitution.

Panic of 1819

The bank's first president was William Jones who resigned as a result of a fraud and embezzlement scandal that consumed the Baltimore branch of the bank and which was exposed during the Panic of 1819. Jones was replaced by Langdon Cheves. Cheves tightened credit at the bank and slashed costs. He also instituted a standing policy of immediately redeeming all state banknotes that came through the bank. This forced the state banks to maintain specie reserves and thereby also tighten credit. The state banks maintained specie reserves by squeezing debtors. The recession following the Panic lasted three years and in the popular imagination was the fault of the Second Bank.

Having restored a sound economy, Cheves resigned in 1822. The bank's last president was Nicholas Biddle (1786-1844), an upper-class, well-educated man of letters with banking expertise.

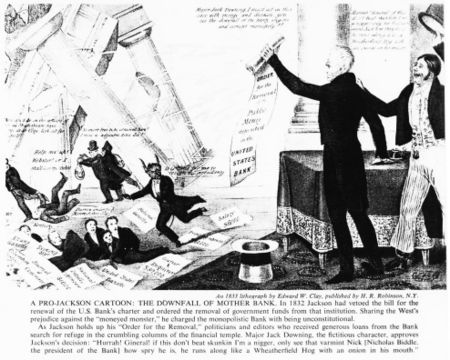

Rechartering

Renewal of the Second Bank's charter was vetoed on July 10, 1832, by Jackson, and it slowly declined until the expiration of its charter in 1836. The bank became a major campaign issue in 1832, with Jackson supported by his newly formed the Democrats and Biddle supported by Henry Clay. Jackson won, and the national charter was not renewed, but Biddle kept the bank in operation using a state charter. The Whigs tried to recharter the bank in August 1841, but President John Tyler vetoed the bill.

Controversy

The Second Bank of the United States helped create a robust economy with strong interregional connections and provided a convenient way for the government to handle its affairs. Enemies of all banks and modernization generally, combined with some jealous bankers, urged Andrew Jackson to destroy it as a monstrous threat to American liberties.[1] The head of the Second Bank during Jackson's presidency was Nicholas Biddle. The bank was created after James Madison and Albert Gallatin found the government unable to finance the War of 1812 after the closing of the First Bank of the United States in 1811.

After the war an economic boom created a need for a strong bank. American agricultural products were in demand in Europe, due to the devastation of the Napoleonic Wars. The Bank aided this boom through its lending. At the time, land sales for speculation were being encouraged. This lending allowed almost anyone to borrow money and speculate in land, sometimes doubling or even tripling the prices of land. The land sales for 1819, alone, totaled some 55 million acres (220,000 km²). With such a boom, hardly anyone noticed the widespread fraud occurring at the Bank.[2]

In the summer of 1818, the national bank managers realized the bank's massive over-extension, and began a policy of contraction and the calling in of loans. This recalling of loans simultaneously curtailed land sales and slowed the American boom boom due to the recovery of Europe. The result was the Panic of 1819 and the situation leading up to McCulloch v. Maryland 17 U.S. 316 (1819). [3]

Maryland adopted a policy to restrict banks, by placing a tax on any bank that was not chartered by the state legislature. This tax was either 2% of all assets or a flat rate of $15,000. That meant that the Baltimore Branch would have to pay this hefty tax. McCulloch filed suit against the state in a county court. The United States Supreme Court struck down the tax; Daniel Webster had successfully argued the case for the bank.

Bank's Decline

By the early 1830s, President Andrew Jackson had come to thoroughly dislike the Second Bank of the United States because of its fraud and corruption. Although its charter was bound to run out in 1836, Jackson wanted to "kill" the Second Bank of the United States even earlier. Jackson is considered primarily responsible for its demise, seeing it as an instrument of political corruption.[4]

Biddle decided to seek an extension of the bank's charter four years early, in 1832. Henry Clay helped to steer the bill through Congress. But Jackson vetoed the bill in July.

In his message on the veto of the bank Jackson used language which appeared to resonate mostly with the common man of the country, while attacking the predominantly rich or foreign stockholders of the current bank. For instance, he explained, "It appears that more than a fourth part of the stock is held by foreigners and the residue is held by a few hundred of our own citizens, chiefly of the richest class. For their benefit does this act exclude the whole American people ... It is but justice and good policy, as far as the nature of this case will admit, to confine our favors to our own fellow-citizens."

Jackson's charter extension veto message inspired Biddle to dismiss the message as a "manifesto of anarchy." Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, who was on retainer as the bank's legal counsel also the Director of its Boston branch, suggested that such language was a political tool, and the entire message a campaign document for Jackson's approaching re-election in 1832. If it was, it was successful. Jackson defeated Clay.

The Second Bank of the United States thrived from the tax revenue that the federal government regularly deposited. Jackson struck at this vital source of funds in 1833 by instructing his Secretary of the Treasury to deposit federal tax revenues in state banks, soon nicknamed "pet banks" because of their loyalty to Jackson's party.

In September, 1833, Secretary of the Treasury Taney transferred the government's Pennsylvania deposits in the Second Bank of the United States to the Bank of Girard in Philadephia. Stephen Girard was a major financier of the War of 1812, including most of the war loan of 1814. He was the original organizer and a major shareholder of the Second Bank.

The Second Bank of the United States soon began to lose money. Nicholas Biddle, desperate to save his bank, called in (demanded payment on) all of his loans and closed the bank to new loans. This angered many of the bank's clients, causing them to pressure Biddle to re-adopt its previous loan policy.

Some anti-Jacksonians converted their outrage into political action. Under guidance from Webster and Clay, in 1834 they formed the Whig Party.[5] If the Whigs and anti-Jackson National Republicans could gain enough votes in Congress in the 1834 election for a 2/3 majority they could override a second Jackson veto, they could extend the bank's charter, but they did not get enough seats and Congress did not send another bank charter extension bill to Jackson.

The Second Bank of the United States was left with little money and, in 1836, its charter expired and it turned into an ordinary bank in Philadelphia. Five years later, the former Second Bank of the United States went bankrupt.[6]

Hammond's interpretation

According to Hammond (1957) in the 1820s and 1830s, the men who sought bank credit were not farmers but businessmen. This debtor class complained not of the burden of debt, but of the difficulty of borrowing; they wanted more credit than was being allowed by the Second Bank. These businessmen opposed credit restrictions and were the leading opponents of the central banking practices by Biddle. Although Jackson denounced the Bank as the 'money power', in reality the Bank was a restraint. The Bank was destroyed primarily by the business interests who used Jackson, and all the agrarian, leveling and Loco-Foco values he personified. When Jackson vetoed the extension of the charter, this was no victory for agrarian democracy (as Jackson claimed). Rather it meant, argues Hammond, the triumph of Wall Street bankers in New York over Biddle in Philadelphia, of unrestrained enterprise over incipient federal control. Thanks to Jacksonian democracy, says Hammond--who was an official of the Federal Reserve in the 1940s and 1950s--the money power increased its power to the detriment of the nation as a whole. And thanks to Andrew Jackson's demagoguery, the American economy was left for almost a century without an effective central monetary authority. Hammond's revisionist interpretation has been largely accepted by historians of all viewpoints, and his book won the Pulitzer Prize in History.

Post-bankruptcy

Despite the demise of the Second Bank of the United States, the building that housed it was not demolished. Since the Bank's closing in 1841, the edifice has performed a variety of functions. As of 2007, it is included as one of the main structures in Independence National Park in downtown Philadelphia, alongside many other important early American structures such as Independence Hall and the Philadelphia Merchants' Exchange. The structure is open daily free of charge and serves as an art gallery, housing a large and famous collection of portraits of prominent early Americans painted by Charles Willson Peale and many others.

Architecture

The architect of the Second Bank of the United States was William Strickland (1788-1854), a former student of Benjamin Latrobe (1764-1820), the man who is often called the first professionally-trained American architect. Latrobe and Strickland were both disciples of the Greek Revival style. Strickland went on to design many other American public buildings in this style, including financial structures such as the branch mints in New Orleans, Dahlonega, and Charlotte, as well as the second building for the main U.S. Mint in Philadelphia in 1833.

Strickland's design for the Second Bank of the United States remains fairly straightforward. The hallmarks of the Greek Revival style can be seen immediately in the north and south façades, which use a large set of steps leading up to the main level platform, known as the stylobate. On top of these, Strickland placed eight severe Doric columns , which are crowned by an entablature containing a triglyph frieze and simple triangular pediment. The building appears much as an ancient Greek temple, hence the stylistic name. The interior consists of an entrance hallway in the center of the north façade flanked by two rooms on either side. The entry leads into two central rooms, one after the other, that span the width of the structure east to west. The east and west sides of the first large room are each pierced by large arched fan window. The building's exterior uses Pennsylvania blue marble, which, due to the manner in which it was cut, has begun to deteriorate from the exposure to the elements of weak parts of the stone. This phenomenon is most visible on the Doric columns of the south façade. Construction lasted from 1819 to 1824.

The Greek Revival style used for the Second Bank contrasts slightly with the earlier, Federal style in architecture used for the First Bank, whose building also still stands and is located nearby in Philadelphia. This can be seen in the more Roman-influenced Federal structure's ornate, colossal Corinthian columns of its façade, which is also embellished by Corinthian pilasters and a symmetric arrangement of sash windows piercing the two stories of the façade. The roofline is also topped by a balustrade and the heavy modillions adorning the pediment give the First Bank an appearance much more like a Roman villa than a Greek temple.