Pain: Difference between revisions

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz (Moved external links to subpage) |

imported>Robert Badgett |

||

| Line 54: | Line 54: | ||

==Treatment== | ==Treatment== | ||

The state of California has stated:<ref name="pmid21149753">{{cite journal| author=Graf J| title=Analgesic use in the elderly: the "pain" and simple truth: comment on "The comparative safety of analgesics in older adults with arthritis". | journal=Arch Intern Med | year= 2010 | volume= 170 | issue= 22 | pages= 1976-8 | pmid=21149753 | doi=10.1001/archinternmed.2010.442 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=21149753 }} </ref> | |||

<blockquote>a patient who suffers from severe chronic intractable pain has the option to chose opioid medications</blockquote> | |||

===Medications=== | ===Medications=== | ||

Especially in chronic pain generally, especially neuropathic or with diffuse pain syndromes such as [[fibromyalgia]], it can be quite unpredictable if a given drug will help a patient, especially when the drug is more a classic analgesic than a drug that works more indirectly. | Especially in chronic pain generally, especially neuropathic or with diffuse pain syndromes such as [[fibromyalgia]], it can be quite unpredictable if a given drug will help a patient, especially when the drug is more a classic analgesic than a drug that works more indirectly. | ||

| Line 96: | Line 99: | ||

===Nonpharmacologic treatments=== | ===Nonpharmacologic treatments=== | ||

Humorous distraction may increase ability to tolerate pain.<ref name="pmidpending">Stuber et al., “Laughter, Humor and Pain Perception in Children: A Pilot Study,” eCAM (October 5, 2007): nem097, {{doi|10.1093/ecam/nem097}} http://ecam.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/nem097v1 (accessed October 30, 2007).</ref> | Humorous distraction may increase ability to tolerate pain.<ref name="pmidpending">Stuber et al., “Laughter, Humor and Pain Perception in Children: A Pilot Study,” eCAM (October 5, 2007): nem097, {{doi|10.1093/ecam/nem097}} http://ecam.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/nem097v1 (accessed October 30, 2007).</ref> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{reflist|2}} | {{reflist|2}} | ||

Revision as of 08:25, 5 April 2011

From birth to losing a loved one, the experience of pain is central to human life. Indeed, it may be argued that people expend most of their time and effort in trying to avoid the pain of hunger, physical injury or emotional hurt. From this perspective, the phenomenon of pain has been the engine for much of technological progress and the advancement of civilisation. This article is a general introduction to the cycle of Citizendium articles on our current understanding of the phenomenon of pain, what it means, how it works, and where humanity may be heading in trying to come to terms with this most basic of experiences.

Pain is not an emotion; it is a specific kind of message sent to the brain from nerves, just as is touch or heat. There are, however, emotional responses as a result of pain.

Acute pain and chronic pain are transmitted on different nerves, and can require quite different treatment. Pain management is a multidisciplinary approach to dealing with difficult acute and chronic pain, but especially the latter. Pain medicine is a specific physician subspecialty, sometimes called pain management, but it should never be forgotten that nursing, pharmacy, other medical specialties, and complementary therapies have a role.

The meaning of pain

The experience of pain is universally and intuitively recognised, but its definition remains controversial. Most people would consider that, by saying that they "have pain", and by giving some indication of where and how severe the hurt is, they are making their experience clear to the listener. The idea that such a subjective communication is the only way we have of knowing what the person is experiencing presents difficulties for those who wish to study pain from either a physical scientific or a philosophical perspective. The scientist and philosopher would like to be able to define the experience of pain, so that it can be analysed, discussed, researched, and understood. Without such an agreed definition, a Tower of Babel like confusion could result.[1] These difficulties are related to the concept of qualia.

The difficulty is because pain is an observation about something that arises inside the sufferer's own body. This is very different from external sense experiences such as vision, hearing or taste, where the stimulus is a clearly definable physical or chemical entity, correlated in a specific way with the word that we use for our perception of that event (e.g. blue, G-flat, or sweet). For pain, the only objective enidence that might correlate with the reported experience is injury to body tissue, yet although an injury may be obvious to an observer, the feeling of pain is not. Pain may be deduced from physical observations, but can be confirmed only by the sufferer. [2]

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) recognised these enigmatic qualities when, in 1994, its committee on taxonomy formulated the IASP definition of pain as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage. [3] This definition applies to pain in humans only, as science cannot evaluate the emotions of animals. There are other definitions of pain, and recent advances in imaging of the brain in pain (e.g. fMRI, SPECT), as well as the identification of biochemical markers of nociceptor nerve activity (e.g. C-fos) may allow more specific descriptions of the phenomenon of pain. At present there is no consistent explanation for how and why people perceive pain in different situations, and in different ways. The idea that some anaesthetists propound that the stress response, spinal metabolic changes and autonomic changes are sufficient to diagnose "pain", when the person is under general anaesthesia, indicates that even in scientific circles there is no consensus about the difference between nociception and pain.[4]

Classification

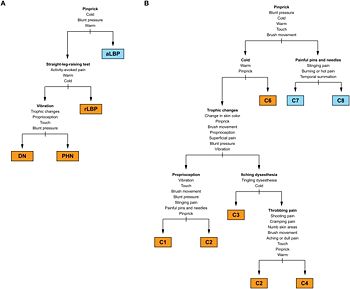

On physical examination, an abnormal response to pinprick (either decreased response or hyperalgesia) is the best discriminator of neuropathic pain and non-neuropathic pain[5]

Nociceptive pain

"Nociception is the term introduced almost 100 years ago by the great physiologist Sherrington (1906) to make clear the distinction between detection of a noxious event or a potentially harmful event and the psychological and other responses to it.[6]"

Nociception is also known as nociperception and physiological pain.

Pain often has a physical cause, an injury to the body outside of the nervous system. In these cases, pain is initiated by mechanical, thermal or chemical changes in non-nervous tissues; this causes activation of specific nerves which relay to spinal centres concerned with the detection of injury, and thence to the thalamus and cortex, as well as to the reticular system. This hard-wired injury detection mode for pain is called "nociception", meaning detection of harm, while the nerves which detect the damage are called nociceptor nerves ("nociceptors" for short).

Common causes of nociceptive pain include traumatic injury (fractures, torn tissue and burns), degenerative conditions such as osteoarthritis, infections and inflammatory conditions such as abscesses or sunburn, and cancers causing tissue breakdown.

Neuropathic pain

A second physical origin for pain is damage to the nociceptor nerves themselves; this is important because it is very difficult to treat, tends to be long standing, and may not be diagnosed easily. In these cases there is no damaged tissue, and no heat, pressure, or release of pain nerve stimulating chemicals at the site where the brain perceives the pain to be coming from, i.e. there is no actual or potential tissue damage in "the area which hurts". It is the spontaneous activity of the damaged and dysfunctional nerves which convey impulses to the spinal cord nociceptor nerve structures, and thence to the higher centres. This mode of the experience of pain is called neuropathic, implying pathology or disease of the nerves themselves. Neuropathic pain may follow injury to a nerve, occurring at the same time as a more general tissue injury, so that nociceptive and neuropathic pain may initially co-exist, the combination often changing to more "pure" neuropathic pain as the tissue injury heals, but the nerves remain dysfunctional. A nerve may be traumatically injured in isolation, or a more generalised nerve injury may result from metabolic diseases such as diabetes, the effects of alcohol abuse, or neurotrophic (nerve) infections such as shingles (Herpes zoster). During its normal development, the brain " learns" to associate the activity of a specific set of pain nerves with injury to a specific body part, so neuropathic pain is felt in the area that would normally be innervated by the damaged nerve, i.e. the person does not perceive the nerve itself to be sore.

Central pain

The third type of pain is caused by damage to the central nervous system, including the spinal cord, structures at the base of the brain (notably the thalamus) and the brain itself. While this may correctly be called neuropathic (pathology of nerve tissue), the clinical and prognostic implications of these pain states has lead to the term "central pain" being applied to these very stubborn pain syndromes. Examples of such syndromes include "spinal cord injury pain" and "post-stroke pain". The central nervous system itself is insensitive to pain (it does not contain nociceptor nerve fibres) and the pain is felt by the sufferer to be located somewhere else in the body, as is the case with peripheral nerve injury.

Psychogenic pain

There is no consensus that psychogenic (in the sense of imaginary) pain exists. If someone were to experience pain as a result of a purely psychiatric disturbance, then presumably the central pain localising and "pain as suffering" paths of the brain would be activated just as in cases of "real" pain, making the condition subjectively indistinguishable from "real physical disease" pain. On the other hand, there are psychological disturbances where persons may complain of pain, act as if in pain, expect others to respond to them as if they are suffering pain, and are not experiencing pain as such, but another feeling such as stiffness or itch. Such illusions of pain are very rare. Because pain is apparently alike in all humans, this semantic error seldom occurs, and the clinical picture tends to be sufficiently inconsistent that the diagnosis would not be difficult to make after a period of conversation about the experience. It should be noted that a person who suffers hallucinations of pain (as opposed to illusions), is really experiencing pain (just as hallucinations of voices are real to the person), so that the complaint would then be consistent, and would need appropriate treatment to reduce the pain.

Finally, the issue of pain complaints as "malingering" remains a social, medical and legal problem. In the cases where the suffering of pain would lead to real benefits for the person, whether psycho-social or financial, involved persons tend to make the diagnosis without necessarily observing the course of the condition adequately. In clinical practice, malingering for financial or personal secondary gain reveals itself (if the person who complains is followed up adequately), as a pattern of inconsistent, irreconcilable, and conflicting actions and complaints. The psychological diagnosis of a "pain disorder" usually presents as persistent and excessive complaints of pain, with no obvious benefits to the person, but often associated with gross, persistent and intractable complaints about painful conditions which most people would consider minor.

Pain measurement

A 1-10 point numeric rating scale and 10 centimeter visual analog scales have been used.

Pain syndromes

Some pain conditions are best described as "pain syndromes"; people with a specific pain syndrome share a defined set of symptoms and signs, the causes of which are poorly understood. Typically, pain syndromes are chronic painful diseases where there is much speculation about the mechanisms and interactions between mind, neuropathology and peripheral tissue abnormalities, and they can have a considerable impact on the sufferer's quality of life. Such syndromes include fibromyalgia syndrome, myofascial pain syndrome, complex regional pain syndrome, failed back syndrome, and post-whiplash injury syndrome.

When a chronic pain syndrome meets specific anatomic distribution criteria, it is categorized as chronic widespread pain

Pain in animals

It is important to consider pain in animals for two quite different reasons. The first is the rather utilitarian consideration that most research that is done in an effort to advance our understanding and treatment of pain in humans is done on experimental animals. If animals do not experience pain as humans do, then this work would not be very helpful, but it is generally considered that the basic mechanisms of pain have been well conserved in the evolution of mammals, and so the mechanisms of pain are likely to be similar in laboratory rodents as in humans. The same is true to some extent also for Cephalopoda, although the pain sensing and processing systems differ in some respects from those of vertebrates

The second reason is that very many people accept that the relief of suffering is an obligation which we have not only to our own kind, but to a varying extent to the animals with which we share this world. In this regard, experimental work on pain, which uses animals as subjects, carries with it the obligation of high ethical standards. This research is important for example for the development of better analagesics and anaesthetics, and to develop treatments for chronic pain. At the same time, however, what is learned about the manifestations and treatment of pain in animals can also be used to help fellow living creatures who suffer pain - the very same species which are used for these experiments.

Treatment

The state of California has stated:[7]

a patient who suffers from severe chronic intractable pain has the option to chose opioid medications

Medications

Especially in chronic pain generally, especially neuropathic or with diffuse pain syndromes such as fibromyalgia, it can be quite unpredictable if a given drug will help a patient, especially when the drug is more a classic analgesic than a drug that works more indirectly.

For example, in chronic neuropathic pain syndromes including reflex sympathetic dystrophy, nerve damage from neuropathy or trauma, or postherpetic neuralgia, there may very well be a role for analgesics, within the model of the WHO pain pyramid. Nevertheless, one or more of a number of classes that are not strictly analgesic may be beneficial:

- Antidepressants, especially tricyclic antidepressants in a lower dose than used for psychiatric conditions

- Anticonvulsants

- Drugs with a stabilizing effect on cardiac muscle, such as calcium channel blockers

- Neurotransmission-affecting topical agents (e.g., capsaicin)

Some pain syndromes, such as migraine, may be managed principally with prophylactic drugs, with "rescue" analgesics for breakthrough pain. Certain specific drugs, such as triptans in migraine, may provide both prophylaxis and interruption of exacerbations, but do not work directly on pain receptors or central pain mechanisms.

Research has addressed switching analgesics when treatment fails.[8]

Opioid analgesics

Opioid analgesics (narcotics) are commonly prescribed, and their usage may be increasing.[9] In emergency rooms, non-Hispanic white patients are more likely to receive narcotics than patients of other ethnicities.[9]

Opioid analgesics may cause more drug toxicity, at least in geriatrics, than non-selective inhibitors of cyclooxygenase (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents) or cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors.[10]

Antidepressants

Antidepressants, especially tricyclic antidepressents, can help neuropathic pain according to a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials by the Cochrane Collaboration.[11]

Comparative studies

- Monotherapy

Regarding the treatment of chronic neuropathic pain in persons with spinal cord injury, a randomized controlled trial found that amitriptyline was more effective than active placebo and possibly better than gabapentin among patients with symptoms of depression while neither gabapentin nor amitriptyline helped patients without depression although there was a statistically insignificant trend favoring amitriptyline. Tricyclic antidepressants are not inferior to gabapentin.[12][13]

For diabetic neuropathy, amitriptyline provided moderate or greater pain relief in 67% of patients as compared to 52% with gabapentin in a randomized cross-over study. In this small study, this result was statistically insignificant.[14]

For diabetic neuropathy, amitriptyline was better than fluoxetine in a randomized controlled trial.[15] In this trial, amitriptyline was effective in patients regardless of whether they had depression, whereas fluoxetine was effective only in depressed patients.

- Combination therapy

Combining gabapentin and nortriptyline may be better than either drug alone.[16]

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents should be avoided in geriatrics according to clinical practice guidelines.[17]

Nonpharmacologic treatments

Humorous distraction may increase ability to tolerate pain.[18]

References

- ↑ Bonica JJ (1979) The need for a taxonomy (editorial). Pain 6:247-52

- ↑ Aydede, Murat, "Pain", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2005 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2005/entries/pain/. Accessed 2007-02-12

- ↑ Merskey H, Bogduk N (eds). Classification of chronic pain. 2nd Ed. IASP Press, Seattle 1994

- ↑ As stated in this this Pain Physiology article, accessed 2007-02-12.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Scholz J, Mannion RJ, Hord DE, et al. (April 2009). "A novel tool for the assessment of pain: validation in low back pain". PLoS Med. 6 (4): e1000047. DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000047. PMID 19360087. PMC 2661253. Research Blogging.

- ↑ "Assessing Pain and Distress: A Veterinary Behaviorist's Perspective by Kathryn Bayne" in "Definition of Pain and Distress and Reporting Requirements for Laboratory Animals: Proceedings of the Workshop Held June 22, 2000 (2000)

- ↑ Graf J (2010). "Analgesic use in the elderly: the "pain" and simple truth: comment on "The comparative safety of analgesics in older adults with arthritis".". Arch Intern Med 170 (22): 1976-8. DOI:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.442. PMID 21149753. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Walker JS, Sheather-Reid RB, Carmody JJ, Vial JH, Day RO (1997). "Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis: support for the concept of "responders" and "nonresponders".". Arthritis Rheum 40 (11): 1944-54. DOI:<1944::AID-ART5>3.0.CO;2-H 10.1002/1529-0131(199711)40:11<1944::AID-ART5>3.0.CO;2-H. PMID 9365082. <1944::AID-ART5>3.0.CO;2-H Research Blogging.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Pletcher MJ, Kertesz SG, Kohn MA, Gonzales R (2008). "Trends in opioid prescribing by race/ethnicity for patients seeking care in US emergency departments". JAMA 299 (1): 70–8. DOI:10.1001/jama.2007.64. PMID 18167408. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Solomon DH, Rassen JA, Glynn RJ, Lee J, Levin R, Schneeweiss S (2010). "The comparative safety of analgesics in older adults with arthritis.". Arch Intern Med 170 (22): 1968-76. DOI:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.391. PMID 21149752. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Saarto T, Wiffen PJ (2007). "Antidepressants for neuropathic pain". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD005454. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD005454.pub2. PMID 17943857. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Rintala DH, Holmes SA, Courtade D, Fiess RN, Tastard LV, Loubser PG (December 2007). "Comparison of the effectiveness of amitriptyline and gabapentin on chronic neuropathic pain in persons with spinal cord injury". Arch Phys Med Rehabil 88 (12): 1547–60. DOI:10.1016/j.apmr.2007.07.038. PMID 18047869. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Chou, Roger; Susan Carson, Benjamin Chan (2009-02-01). "Gabapentin Versus Tricyclic Antidepressants for Diabetic Neuropathy and Post-Herpetic Neuralgia: Discrepancies Between Direct and Indirect Meta-Analyses of Randomized Controlled Trials". Journal of General Internal Medicine 24 (2): 178-188. DOI:10.1007/s11606-008-0877-5. Retrieved on 2009-01-26. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Morello CM, Leckband SG, Stoner CP, Moorhouse DF, Sahagian GA (September 1999). "Randomized double-blind study comparing the efficacy of gabapentin with amitriptyline on diabetic peripheral neuropathy pain". Arch. Intern. Med. 159 (16): 1931–7. PMID 10493324. [e]

- ↑ Max MB, Lynch SA, Muir J, Shoaf SE, Smoller B, Dubner R (May 1992). "Effects of desipramine, amitriptyline, and fluoxetine on pain in diabetic neuropathy". N. Engl. J. Med. 326 (19): 1250–6. PMID 1560801. [e]

- ↑ Gilron I et al. (2009) Nortriptyline and gabapentin, alone and in combination for neuropathic pain: a double-blind, randomised controlled crossover trial. Lancet DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61081-3

- ↑ The American Geriatrics Society - Education - AGS Clinical Practice Guideline: Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons.

- ↑ Stuber et al., “Laughter, Humor and Pain Perception in Children: A Pilot Study,” eCAM (October 5, 2007): nem097, DOI:10.1093/ecam/nem097 http://ecam.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/nem097v1 (accessed October 30, 2007).

- Pages using PMID magic links

- CZ Live

- Health Sciences Workgroup

- Philosophy Workgroup

- Psychology Workgroup

- Pain management Subgroup

- Anesthesiology Subgroup

- Articles written in British English

- Advanced Articles written in British English

- All Content

- Health Sciences Content

- Philosophy Content

- Psychology Content

- Pain management tag

- Anesthesiology tag