CZ:Featured article/Current: Difference between revisions

imported>Chunbum Park mNo edit summary |

imported>John Stephenson (template) |

||

| (216 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{:{{FeaturedArticleTitle}}}} | |||

<small> | |||

==Footnotes== | |||

{{reflist|2}} | |||

</small> | |||

{{ | |||

Latest revision as of 10:19, 11 September 2020

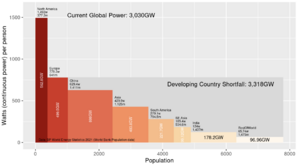

After decades of failure to slow the rising global consumption of coal, oil and gas,[1] many countries have proceeded as of 2024 to reconsider nuclear power in order to lower the demand for fossil fuels.[2] Wind and solar power alone, without large-scale storage for these intermittent sources, are unlikely to meet the world's needs for reliable energy.[3][4][5] See Figures 1 and 2 on the magnitude of the world energy challenge.

Nuclear power plants that use nuclear reactors to create electricity could provide the abundant, zero-carbon, dispatchable[6] energy needed for a low-carbon future, but not by simply building more of what we already have. New innovative designs for nuclear reactors are needed to avoid the problems of the past.

Fig.1 Electricity consumption may soon double, mostly from coal-fired power plants in the developing world.[7]

Issues Confronting the Nuclear Industry

New reactor designers have sought to address issues that have prevented the acceptance of nuclear power, including safety, waste management, weapons proliferation, and cost. This article will summarize the questions that have been raised and the criteria that have been established for evaluating these designs. Answers to these questions will be provided by the designers of these reactors in the articles on their designs. Further debate will be provided in the Discussion and the Debate Guide pages of those articles.

Footnotes

- ↑ Global Energy Growth by Our World In Data

- ↑ Public figures who have reconsidered their stance on nuclear power are listed on the External Links tab of this article.

- ↑ Pumped storage is currently the most economical way to store electricity, but it requires a large reservoir on a nearby hill or in an abandoned mine. Li-ion battery systems at $500 per KWh are not practical for utility-scale storage. See Energy Storage for a summary of other alternatives.

- ↑ Utilities that include wind and solar power in their grid must have non-intermittent generating capacity (typically fossil fuels) to handle maximum demand for several days. They can save on fuel, but the cost of the plant is the same with or without intermittent sources.

- ↑ Mark Jacobson believes that long-distance transmission lines can provide an alternative to costly storage. See the bibliography for more on this proposal and the critique by Christopher Clack.

- ↑ "Load following" is the term used by utilities, and is important when there is a lot of wind and solar on the grid. Some reactors are not able to do this.

- ↑ Fig.1.3 in Devanney "Why Nuclear Power has been a Flop"