Energy balance in pregnancy and lactation: Difference between revisions

imported>Joseph Tomlinson |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (50 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

Maintaining '''energy balance in pregnancy and lactation''' entails many physiological adaptations to support foetal growth, [[parturition]] and lactation. Hormonal changes occur in anticipation of the increased energy expenditure and high metabolic demands of late [[pregnancy]] and [[lactation]], and during pregnancy, increased [[appetite|food intake]] is accompanied by an increase in [[adipocyte|fat mass]]. | |||

== | An individual’s requirement for essential nutrients corresponds to the amount of food they need to consume to meet his/her energy needs. When a woman becomes pregnant, she needs to gain weight at a rate consistent with good health for herself and her child. The recommendations for energy intake for women vary depending on their background (population-specific); the energy requirements are different for well-nourished women from developed countries compared to shorter women from developing countries.<ref name=Butte05>Butte NF, King JC (2005) Energy requirements during pregnancy and lactation ''Public Health Nutr'' 8:1010-27 </ref><ref name=Forsum07>Forsum E, Lof M (2007) Energy metabolism during human pregnancy ''Annu Rev Nutr'' 27:277-92</ref> | ||

Obesity is a major risk factor in pregnant and lactating women, and has adverse effects on the fetus. Difficulty estimating delivery date due to irregular [[menstrual cycle]]s, problems performing preinvasive tests such as amniocentesis, increased incidence of [[cleft palate]] and a increased risk of miscarriage are some of the problems obese pregnant women might face. Furthermore, post pregnancy, obese women are less likely to initiate lactation. Foetal pre-programming is affected by maternal obesity, and this can increase the probability of the offspring being obese when older. | |||

==Energy Metabolism== | |||

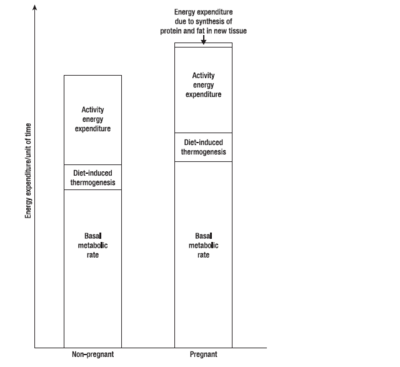

During pregnancy, women gain weight which comprises of the products of conception (foetus, [[placenta]], [[amniotic fluid]]), the increases of various maternal tissues ([[uterus]], [[breast]]s, blood, extracellular extravascular fluid), and the increases in maternal fat stores. Accordingly, the energy cost of maintaining tissue mass (the ''[[basal metabolic rate]]'', BMR), is higher in pregnancy - as are the energy costs of physical exercise. During pregnancy and lactation, numerous metabolic adjustments are needed to ensure that a constant supply of fuel (in the form of [[glucose]] and [[amino acid]]s) reaches the foetus.<ref name=Butte99>Butte NF ''et al.'' (1999) Adjustments in energy expenditure and substrate utilization during late pregnancy and lactation ''Am J Clin Nutr'' 69:299-307</ref> | |||

{{Image|Pregnancymetabolism.PNG|right|400px|Energy expenditure in pregnant vs nonpregnant women. Adapted from (Forsum 2007)}} | |||

During the first, second and third trimesters, BMR increases by (on average) 4%, 10% and 24% respectively, although different women vary considerably. Women from developing countries show a smaller increase in BMR than those from developed countries, while women with high prepregnant BMI show larger increases. Thus changes in BMR during pregnancy are largely a function of maternal nutritional status. | |||

To sustain the foetus’ growth, the mother must continuously supply it with nutrients. Although the placenta is almost impermeable to [[lipid]]s (other than [[free fatty acid]]s and ketone bodies) lipid metabolism is strongly affected during pregnancy. In the first two semesters, foetal growth is minimal and her increased food intake causes fat store accumulation. In the last trimester, the foetus grows rapidly, sustained by nutrient transfer across the placenta. In this phase, the mother switches to a catabolic condition; lipid stores are broken down, and glucose is the most abundant nutrient that crosses the placenta at this point.<ref name=Herrera00>Herrera E (2000) Metabolic adaptations in pregnancy and their implications for the availability of substrates to the fetus ''Eur J Clin Nutr'' 54:S47-S51 </ref> | |||

The energy requirement of a pregnant woman is the amount of energy intake from food that is needed to balance her energy expenditure, while maintaining a body size and composition and a level of physical activity consistent with good health, and with economic and social needs. This includes the energy needs associated with the deposition of tissue consistent with optimal pregnancy outcome. <ref name=Butte05/> | |||

<ref | |||

== Changes of hormone interactions and appetite regulators during pregnancy and lactation == | == Changes of hormone interactions and appetite regulators during pregnancy and lactation == | ||

Appetite regulation during pregnancy and lactation involves different neuronal pathways. During pregnancy, changes in the expression of the orexigenic neuropeptides [[neuropeptide Y]] (NPY) and [[agouti-related peptide]] (AgRP), and induced [[leptin]] resistance contribute to increased appetite, while other mechanisms associated with offspring stimulation are thought to maintain hyperphagia during lactation <ref name=Makarova10>Makarova EN ''et al.'' (2010)Regulation of food consumption during pregnany and lactaion in mice ''Neurosci Behav Physiol'' 40:263-7</ref>. | |||

Both NPY and AgRP mRNA expression increase during pregnancy and decrease again after parturition. While NPY mRNA expression levels remain constant during the end of pregnancy, AgRP mRNA expression increases at the end of pregnancy, and this may be responsible for theincrease in food consumption. During pregnancy, central injections of α-MSH do not decrease food intake, suggesting that a α-MSH resistant state is also maintained during pregnancy <ref name=Faas10> Faas MM ''et al.'' (2010) A brief review on how pregnancy and sex hormones interfere with taste and food intake ''Chem Percept'' 3:51-6 </ref> | |||

NPY knock-out (KO) mice have normal food intake during lactation <ref name=Makarova10/>. | |||

===Development of leptin and insulin resistance during different reproductive states=== | ===Development of leptin and insulin resistance during different reproductive states=== | ||

During pregnancy, an increase in maternal energy reserves is needed to help meet the increased metabolic demands of foetal development and lactation. As a result of this increased adiposity, plasma leptin levels are elevated, but, during pregnancy, these increased leptin levels do not suppress food intake as they would be expected to <ref name=Drattan07>Drattan DR ''et al.'' (2007) Hormonal induction of leptin resistance during pregnancy ''Physiol Behav'' 91:366-74</ref>. Recorded increases in leptin levels during pregnancy is now thought to be necessary for regulating foetal growth and development . After parturition, leptin levels decrease and leptin sensitivity is recovered. | |||

During pregnancy, leptin insensitivity develops , as studies using pregnant rats at the beginning of gestation show a decrease in food intake in response to direct leptin infusion <ref name=Ladyman10>Layman SR ''et al.'' (2010) Hormone interactions regulating energy balance during pregnancy ''J Neuroendocrinol'' 22:805-17</ref>. Thus initial hyperphagia, induced by pregnancy, is thought to be caused by other hormonal changes which occur in the early stages of pregnancy. As obesity can be caused by leptin insensitivity and resistance within the [[hypothalamus]], pregnancy may provide a new unique, leptin resistance model to investigate the underlying mechanisms of leptin resistance associated with obesity. As there is no evidence of a down regulation of leptin receptors in the arcuate nuclease during pregnancy, leptin resistance may be caused by an increase in specific sex hormones during early pregnancy. | |||

As obesity can be caused by leptin insensitivity and resistance within the hypothalamus, pregnancy may provide a new unique, leptin resistance model to investigate the underlying mechanisms of leptin resistance associated with obesity | |||

===Roles of prolactin, progesterone and placental lactogen in leptin resistance === | ===Roles of prolactin, progesterone and placental lactogen in leptin resistance === | ||

Increases in food intake occur early in pregnancy when the energy demands of the foetus are still low. This observation has lead to the investigation of the roles of sex hormones in leptin resistance and hyperphagia. | |||

It has been suggested that progesterone stimulates appetite and food intake in pregnant females, even in the presence of leptin. | |||

Prolactin surges during early pregnancy stimulate orexigenic responses which are thought to include the stimulation of progesterone secretion. Placental lactogen is then thought to maintain hyperphagia by increasing leptin levels. Recorded elevated leptin levels in the pregnant female are too slow to induce leptin resistance, hence it is assumed that prolactin and placental lactogen induce leptin resistance during pregnancy <ref name=Henson06>Henson MC, Castracane VD(2006) Leptin in pregnancy: an update ''Biol Reprod'' 74:218-29</ref>. | |||

Prolactin surges during early pregnancy stimulate | |||

Studies using [[pseudopregnant]] rats have demonstrated that chronic prolactin infusion, used to mimic placental lactogen patterns during pregnancy, inhibit the action of leptin to suppress food intake <ref name=Ladyman10/>. | Studies using [[pseudopregnant]] rats have demonstrated that chronic prolactin infusion, used to mimic placental lactogen patterns during pregnancy, inhibit the action of leptin to suppress food intake <ref name=Ladyman10/>. | ||

== | == Problems associated with obesity during pregnancy == | ||

Obesity represents a major risk factor in pregnant and lactating women and has documented adverse effects on both pregnancy and the fetus. Alarmingly 35% of the women who died from maternal death had a BMI >30 according to the 'Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths' <ref name=Metwally07>Metwally M ''et al.'' (2007) The impact of obesity on female reproductive function ''Obesity'' 8: 515e23</ref>. | |||

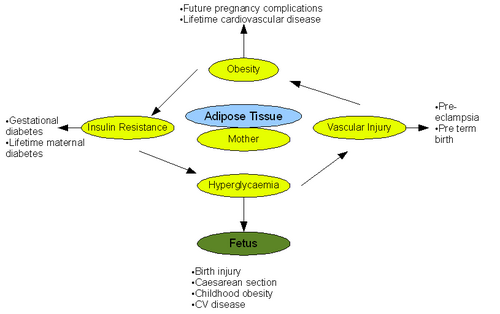

{{Image|Pregnancy.png|right|500px|The pathological effects of obesity on pregnancy and fetal outcome. Adapted from (Smith et al 2008)}} | |||

===Antepartum Implications=== | ===Antepartum Implications=== | ||

Antepartum refers to the period of pregnancy before birth. Obesity has numerous implications on this stage of pregnancy. General physiological examination, namely ultrasound and blood pressure measurement, is difficult to perform due to excess fat tissue. This lead to difficulties in assessing the state of fetus <ref name=Wuntakal09>Wuntakal ''et al.'' (2009) The implications of obesity on pregnancy. Obstetrics, gynaecology and reproductive medicine 19:12 344-349</ref>. Obesity has also been shown to irregulate menstrual cycles making estimation of delivery date difficult. Further complexities arise when performing preinvasive tests such as amiocentesis. Risk of miscarriage increases greatly after such tests in obese women. It was reported that fetal loss was 4.4% in women with BMI >25 compared to 1% in women with BMI <20 <ref name=Wuntakal09/>. Studies comparing normal weight women with obese women have also shown that there is an increased risk of neural tube defect in the fetuses of the obese mothers. This leads to increased incidence of cleft palate. <ref name=Smith08>Smith ''et al.'' (2008) Effects of obesity on pregnancy ''J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs'' 37:176-84 PMID 18336441</ref>. Pre-eclampsia is also tripled when BMI >30 due to the association of obesity with chronic inflammation, oxidative stress and insulin resistance <ref name=Wuntakal09/>. A further, well documented implication of obesity on the antepartum phase is increased incidence of gestational diabetes. The risk increases significantly with an increase in BMI due to increased impaired glucose intolerance. Moreover gestational diabetes develops earlier in pregnancy in obese mothers, resulting in delayed diagnosis and treatment. Incidence of gestational diabetes can be up to twenty times greater in women with BMI >30 <ref name=Langer05>Langer O ''et al.'' (2005) Overweight and obese in gestational diabetes: the impact on pregnancy outcome ''Am J Obs Gynecol'' 192:1768-76 PMID 15970805</ref> | |||

Antepartum refers to the period of pregnancy before birth. Obesity has numerous implications on this stage of pregnancy. General physiological examination, namely ultrasound and blood pressure measurement, is difficult to perform due to excess fat tissue. This lead to difficulties in assessing the state of fetus <ref name=Wuntakal09>Wuntakal et al (2009) The implications of obesity on pregnancy. Obstetrics, gynaecology and reproductive medicine 19:12 344-349</ref>. Obesity has also been shown to irregulate menstrual cycles making estimation of delivery date difficult. Further complexities arise when performing preinvasive tests such as amiocentesis. Risk of miscarriage increases greatly after such tests in obese women. It was reported that fetal loss was 4.4% in women with BMI >25 compared to 1% in women with BMI <20 <ref name=Wuntakal09/>. Studies comparing normal weight women with obese women have also shown that there is an increased risk of neural tube defect in the fetuses of the obese mothers. This leads to increased incidence of cleft palate. <ref name=Smith08>Smith et al (2008) Effects of obesity on pregnancy | |||

O et al (2005) Overweight and obese in gestational diabetes: the impact on pregnancy outcome | |||

===Intrapartum Implications=== | ===Intrapartum Implications=== | ||

The intrapartum phase of pregnancy refers to the period of giving birth. As in the antepartum phase, physical examination is difficult in obese women. In obese women an ultrasound is usually performed to assess the presentation of the fetus before birth. In normal weight women this is done far more efficiently through abdominal assessment. Monitoring the heart rate of the fetus during birth is also challenging in obese mothers and involves the use of a fetal scalp electrode. This will immobilise the pregnant mother and increase the risk of thromboembolism. As a result, obese women must adopt preventative measures for thromboembolism. The gestation period is often longer than forty weeks in obese women, and this leads to increased rates of induced labour compared to normal weight women. Perhaps the greatest implication of obesity concerns contractions during childbirth. The myometrium of obese women is less contractile than normal due to inhibition of contractions by excess leptin. The inhibitory effect of leptin during childbirth leads to reduced frequency and amplitude of myometrium contractions and therefore an increased necessity for caesarean section in obese women. Rates of caesarean section have been reported as 31% in obese women compared to 22% in normal weight women. Performing a caesarean section on obese women is technically very challenging due to physiological reasons. These include the need for a deeper incision, difficulty in accessing the lower segment and a larger panniculus. Leptin inhibition could also explain the aforementioned need for increased induced labour in obese women. Obesity in pregnant women can lead to anaesthetic problems during childbirth. Cutaneous veins are often obstructed in obese women and this makes intravenous access either difficult. Longer needles are also required to reach the spinal and epidural space. These technical challenges mean an experienced senior anaesthetist is usually required.<ref name=Wuntakal09/>.<ref name=Cedergren09>Cedergren IM (2009) Non-elective caesarean delivery due to ineffective uterine contractility or due to obstructed labour in relation to maternal body mass index ''Eur J Obs Gynaecol Reprod Biol'' 145:163-6 PMID 19525054</ref>. | |||

The intrapartum phase of pregnancy refers to the period of giving birth. | |||

===Postpartum Implications=== | ===Postpartum Implications=== | ||

Emergency procedures, including caesarean section, are much more common in obese women compared to normal weight women. Post-operative complications and increased morbidity following such procedures are linked strongly to obesity. Although rare, one of the greatest risks of pregnancy and puerperium (6 weeks following birth) is venous thromboembolism. Obese women are at a much greater risk of developing deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Obese women must therefore undertake measure to prevent venous thromboembolism after giving birth during the puerperium period. Measures may include TED stockings and administration of low molecular weight heparin <ref name=Wuntakal09/>. | |||

== | ===Implications of obesity on lactation=== | ||

The impact of obesity on lactation is poorly understood. However, obese women are much less likely to initiate lactation, they have delayed lactogenesis, and are far more prone to early cessation of breastfeeding than normal weight woment <ref name=Jevitt07>Jevitt C ''et al.'' (2007) Lactation complicated by overweight and obesity: Supporting the mother and newborn ''J Midwifery Womens Health'' 52:606-13 PMID 17983998</ref>. | |||

== | |||

<ref> | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{reflist | 2}}[[Category:Suggestion Bot Tag]] | |||

Latest revision as of 11:00, 12 August 2024

Maintaining energy balance in pregnancy and lactation entails many physiological adaptations to support foetal growth, parturition and lactation. Hormonal changes occur in anticipation of the increased energy expenditure and high metabolic demands of late pregnancy and lactation, and during pregnancy, increased food intake is accompanied by an increase in fat mass.

An individual’s requirement for essential nutrients corresponds to the amount of food they need to consume to meet his/her energy needs. When a woman becomes pregnant, she needs to gain weight at a rate consistent with good health for herself and her child. The recommendations for energy intake for women vary depending on their background (population-specific); the energy requirements are different for well-nourished women from developed countries compared to shorter women from developing countries.[1][2]

Obesity is a major risk factor in pregnant and lactating women, and has adverse effects on the fetus. Difficulty estimating delivery date due to irregular menstrual cycles, problems performing preinvasive tests such as amniocentesis, increased incidence of cleft palate and a increased risk of miscarriage are some of the problems obese pregnant women might face. Furthermore, post pregnancy, obese women are less likely to initiate lactation. Foetal pre-programming is affected by maternal obesity, and this can increase the probability of the offspring being obese when older.

Energy Metabolism

During pregnancy, women gain weight which comprises of the products of conception (foetus, placenta, amniotic fluid), the increases of various maternal tissues (uterus, breasts, blood, extracellular extravascular fluid), and the increases in maternal fat stores. Accordingly, the energy cost of maintaining tissue mass (the basal metabolic rate, BMR), is higher in pregnancy - as are the energy costs of physical exercise. During pregnancy and lactation, numerous metabolic adjustments are needed to ensure that a constant supply of fuel (in the form of glucose and amino acids) reaches the foetus.[3]

During the first, second and third trimesters, BMR increases by (on average) 4%, 10% and 24% respectively, although different women vary considerably. Women from developing countries show a smaller increase in BMR than those from developed countries, while women with high prepregnant BMI show larger increases. Thus changes in BMR during pregnancy are largely a function of maternal nutritional status.

To sustain the foetus’ growth, the mother must continuously supply it with nutrients. Although the placenta is almost impermeable to lipids (other than free fatty acids and ketone bodies) lipid metabolism is strongly affected during pregnancy. In the first two semesters, foetal growth is minimal and her increased food intake causes fat store accumulation. In the last trimester, the foetus grows rapidly, sustained by nutrient transfer across the placenta. In this phase, the mother switches to a catabolic condition; lipid stores are broken down, and glucose is the most abundant nutrient that crosses the placenta at this point.[4]

The energy requirement of a pregnant woman is the amount of energy intake from food that is needed to balance her energy expenditure, while maintaining a body size and composition and a level of physical activity consistent with good health, and with economic and social needs. This includes the energy needs associated with the deposition of tissue consistent with optimal pregnancy outcome. [1]

Changes of hormone interactions and appetite regulators during pregnancy and lactation

Appetite regulation during pregnancy and lactation involves different neuronal pathways. During pregnancy, changes in the expression of the orexigenic neuropeptides neuropeptide Y (NPY) and agouti-related peptide (AgRP), and induced leptin resistance contribute to increased appetite, while other mechanisms associated with offspring stimulation are thought to maintain hyperphagia during lactation [5].

Both NPY and AgRP mRNA expression increase during pregnancy and decrease again after parturition. While NPY mRNA expression levels remain constant during the end of pregnancy, AgRP mRNA expression increases at the end of pregnancy, and this may be responsible for theincrease in food consumption. During pregnancy, central injections of α-MSH do not decrease food intake, suggesting that a α-MSH resistant state is also maintained during pregnancy [6] NPY knock-out (KO) mice have normal food intake during lactation [5].

Development of leptin and insulin resistance during different reproductive states

During pregnancy, an increase in maternal energy reserves is needed to help meet the increased metabolic demands of foetal development and lactation. As a result of this increased adiposity, plasma leptin levels are elevated, but, during pregnancy, these increased leptin levels do not suppress food intake as they would be expected to [7]. Recorded increases in leptin levels during pregnancy is now thought to be necessary for regulating foetal growth and development . After parturition, leptin levels decrease and leptin sensitivity is recovered. During pregnancy, leptin insensitivity develops , as studies using pregnant rats at the beginning of gestation show a decrease in food intake in response to direct leptin infusion [8]. Thus initial hyperphagia, induced by pregnancy, is thought to be caused by other hormonal changes which occur in the early stages of pregnancy. As obesity can be caused by leptin insensitivity and resistance within the hypothalamus, pregnancy may provide a new unique, leptin resistance model to investigate the underlying mechanisms of leptin resistance associated with obesity. As there is no evidence of a down regulation of leptin receptors in the arcuate nuclease during pregnancy, leptin resistance may be caused by an increase in specific sex hormones during early pregnancy.

Roles of prolactin, progesterone and placental lactogen in leptin resistance

Increases in food intake occur early in pregnancy when the energy demands of the foetus are still low. This observation has lead to the investigation of the roles of sex hormones in leptin resistance and hyperphagia. It has been suggested that progesterone stimulates appetite and food intake in pregnant females, even in the presence of leptin.

Prolactin surges during early pregnancy stimulate orexigenic responses which are thought to include the stimulation of progesterone secretion. Placental lactogen is then thought to maintain hyperphagia by increasing leptin levels. Recorded elevated leptin levels in the pregnant female are too slow to induce leptin resistance, hence it is assumed that prolactin and placental lactogen induce leptin resistance during pregnancy [9]. Studies using pseudopregnant rats have demonstrated that chronic prolactin infusion, used to mimic placental lactogen patterns during pregnancy, inhibit the action of leptin to suppress food intake [8].

Problems associated with obesity during pregnancy

Obesity represents a major risk factor in pregnant and lactating women and has documented adverse effects on both pregnancy and the fetus. Alarmingly 35% of the women who died from maternal death had a BMI >30 according to the 'Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths' [10].

Antepartum Implications

Antepartum refers to the period of pregnancy before birth. Obesity has numerous implications on this stage of pregnancy. General physiological examination, namely ultrasound and blood pressure measurement, is difficult to perform due to excess fat tissue. This lead to difficulties in assessing the state of fetus [11]. Obesity has also been shown to irregulate menstrual cycles making estimation of delivery date difficult. Further complexities arise when performing preinvasive tests such as amiocentesis. Risk of miscarriage increases greatly after such tests in obese women. It was reported that fetal loss was 4.4% in women with BMI >25 compared to 1% in women with BMI <20 [11]. Studies comparing normal weight women with obese women have also shown that there is an increased risk of neural tube defect in the fetuses of the obese mothers. This leads to increased incidence of cleft palate. [12]. Pre-eclampsia is also tripled when BMI >30 due to the association of obesity with chronic inflammation, oxidative stress and insulin resistance [11]. A further, well documented implication of obesity on the antepartum phase is increased incidence of gestational diabetes. The risk increases significantly with an increase in BMI due to increased impaired glucose intolerance. Moreover gestational diabetes develops earlier in pregnancy in obese mothers, resulting in delayed diagnosis and treatment. Incidence of gestational diabetes can be up to twenty times greater in women with BMI >30 [13]

Intrapartum Implications

The intrapartum phase of pregnancy refers to the period of giving birth. As in the antepartum phase, physical examination is difficult in obese women. In obese women an ultrasound is usually performed to assess the presentation of the fetus before birth. In normal weight women this is done far more efficiently through abdominal assessment. Monitoring the heart rate of the fetus during birth is also challenging in obese mothers and involves the use of a fetal scalp electrode. This will immobilise the pregnant mother and increase the risk of thromboembolism. As a result, obese women must adopt preventative measures for thromboembolism. The gestation period is often longer than forty weeks in obese women, and this leads to increased rates of induced labour compared to normal weight women. Perhaps the greatest implication of obesity concerns contractions during childbirth. The myometrium of obese women is less contractile than normal due to inhibition of contractions by excess leptin. The inhibitory effect of leptin during childbirth leads to reduced frequency and amplitude of myometrium contractions and therefore an increased necessity for caesarean section in obese women. Rates of caesarean section have been reported as 31% in obese women compared to 22% in normal weight women. Performing a caesarean section on obese women is technically very challenging due to physiological reasons. These include the need for a deeper incision, difficulty in accessing the lower segment and a larger panniculus. Leptin inhibition could also explain the aforementioned need for increased induced labour in obese women. Obesity in pregnant women can lead to anaesthetic problems during childbirth. Cutaneous veins are often obstructed in obese women and this makes intravenous access either difficult. Longer needles are also required to reach the spinal and epidural space. These technical challenges mean an experienced senior anaesthetist is usually required.[11].[14].

Postpartum Implications

Emergency procedures, including caesarean section, are much more common in obese women compared to normal weight women. Post-operative complications and increased morbidity following such procedures are linked strongly to obesity. Although rare, one of the greatest risks of pregnancy and puerperium (6 weeks following birth) is venous thromboembolism. Obese women are at a much greater risk of developing deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Obese women must therefore undertake measure to prevent venous thromboembolism after giving birth during the puerperium period. Measures may include TED stockings and administration of low molecular weight heparin [11].

Implications of obesity on lactation

The impact of obesity on lactation is poorly understood. However, obese women are much less likely to initiate lactation, they have delayed lactogenesis, and are far more prone to early cessation of breastfeeding than normal weight woment [15].

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Butte NF, King JC (2005) Energy requirements during pregnancy and lactation Public Health Nutr 8:1010-27

- ↑ Forsum E, Lof M (2007) Energy metabolism during human pregnancy Annu Rev Nutr 27:277-92

- ↑ Butte NF et al. (1999) Adjustments in energy expenditure and substrate utilization during late pregnancy and lactation Am J Clin Nutr 69:299-307

- ↑ Herrera E (2000) Metabolic adaptations in pregnancy and their implications for the availability of substrates to the fetus Eur J Clin Nutr 54:S47-S51

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Makarova EN et al. (2010)Regulation of food consumption during pregnany and lactaion in mice Neurosci Behav Physiol 40:263-7

- ↑ Faas MM et al. (2010) A brief review on how pregnancy and sex hormones interfere with taste and food intake Chem Percept 3:51-6

- ↑ Drattan DR et al. (2007) Hormonal induction of leptin resistance during pregnancy Physiol Behav 91:366-74

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Layman SR et al. (2010) Hormone interactions regulating energy balance during pregnancy J Neuroendocrinol 22:805-17

- ↑ Henson MC, Castracane VD(2006) Leptin in pregnancy: an update Biol Reprod 74:218-29

- ↑ Metwally M et al. (2007) The impact of obesity on female reproductive function Obesity 8: 515e23

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Wuntakal et al. (2009) The implications of obesity on pregnancy. Obstetrics, gynaecology and reproductive medicine 19:12 344-349

- ↑ Smith et al. (2008) Effects of obesity on pregnancy J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 37:176-84 PMID 18336441

- ↑ Langer O et al. (2005) Overweight and obese in gestational diabetes: the impact on pregnancy outcome Am J Obs Gynecol 192:1768-76 PMID 15970805

- ↑ Cedergren IM (2009) Non-elective caesarean delivery due to ineffective uterine contractility or due to obstructed labour in relation to maternal body mass index Eur J Obs Gynaecol Reprod Biol 145:163-6 PMID 19525054

- ↑ Jevitt C et al. (2007) Lactation complicated by overweight and obesity: Supporting the mother and newborn J Midwifery Womens Health 52:606-13 PMID 17983998