Tall tale: Difference between revisions

imported>Bessel Dekker mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (15 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

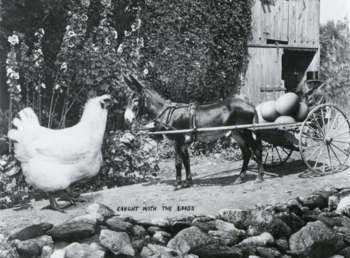

A | {{Image|Tall-tale Postcard - Caught With the Goods.png|right|350px|A [[tall-tale postcard]] based on a [[photomontage]], illustrating the kind of [[exaggeration]] typical for tall tales: A [[dwarf]] drives a [[cart]], drawn by a [[mule]], filled with giant [[egg]]s. The dwarf is wearing a [[suit (clothing)|suit]] and a [[top hat]]. The mule is being confronted on the road by a giant [[chicken]].}} | ||

A '''[[tall tale]]''' is a narrative, song or jest that depicts exaggerated situations, incredible boasts or impossible achievements. In a narrow sense, the term applies to stories told by American frontiersmen, and indeed the term itself originates from the mid-1800s.<ref> ''SOED '' s.v. “tall II".</ref> In a wider sense, however, a tall tale is a specimen of mendacious literature, often a folk narrative, whether or not recorded in writing. Written forms, however, also exist as literary creations in their own right. As such, the genre is considered to be universal and of all ages.<ref>P.J. Meertens, “Leugenliteratuur”, in: A.G.H. Bachrach et al., ''Moderne Encyclopedie van de Wereldliteratuur '', vol. 5. Haarlem/Antwerpen 1982:328-29</ref> | |||

Tall tales are not just fictitious, they are patently impossible. If the tall tale is a first-person narrative, the narrator pretends to believe his own story,<ref>Meertens 1982:328-29</ref> while in third-person narratives, the account is likewise presented as true. It is a characteristic of the tall tale that it is told by a liar, not by a [[fallible narrator]]. While delimitations are difficult to draw sharply, tall tales should therefore be distinguished from [[fable]]s (which characteristically present a moral) and from [[science fiction]] or science fantasy (which by its very nature presents itself as a fantasy). | |||

==The American tradition== | |||

Tall tales in the American folk tale tradition often snowball round such well-known figures as [[Bill Cody]] and [[Davy Crockett]]. But there is also a New England tradition, including the tale of Captain Stormalong, who, caught in a storm, steered his ship through the Panama Isthmus, thus digging the canal. Apart from the oral tradition, there are literary specimens by [[Washington Irving]] (''History of New York'', 1809) and [[Mark Twain]] (''Life on the Mississippi'', 1883).<ref>''Merriam Webster’s Encyclopedia of Literature'', Springfield 1995 s.v. “tall tale”</ref> | |||

==A discontinuous history: mendacious literature== | |||

===Non-Western traditions=== | |||

Because lies are of all ages, mendacious literature, whether oral or written, has had a long tradition and seems to occur all over the world. Certain themes recur internationally. Mendacious stories in other cultures include those in the ''One thousand and One Nights'', while they are also found in the Talmud.<ref>Meertens 1982:328-29</ref> | |||

===The Western tradition=== | |||

In Western Europe, the precursor is Lucian of Samosata, who lived in the second century, and whose account of his sea voyage is packed with marvels. Of much later date is the eleventh-century ''Modus florum'', where the lie is explicit: by telling mendacious stories, the protagonist is accepted as suitor to the king’s daughter.<ref>Meertens 1982:328-29</ref> | |||

====Riddles, lies, and wishes==== | |||

Mendacious songs from the Middle Ages have been handed down in song books. They occupy a position in between other fantastic genres, such as riddles and wish-fulfilment songs. Riddles may depict the impossible or the seemingly impossible. Thus, a bird without wings is a recurring motif, but in certain contexts, it is revealed to stand for something else: it may then be a metaphor for a snowflake. By contrast, an actual impossibility is postulated in a sixteenth-century German song, where a young man undertakes to marry a fair maid if she proves capable of weaving silk from straw.<ref>G. Kalff, ‘’Het lied in de middeleeuwen’’, Ch. IV, “Raadsel-, Leugen en Wenschliederen”. Arnhem 1972[1884]:486-93, (online version [http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/kalf003lied01_01/kalf003lied01_01_0006.php] accessed Mar. 9, 2010)</ref> | |||

The lie may be presented as a dream: in one of these songs, the narrator rides a three-legged ox around the world, but while he acknowledges that this is something he has dreamt, let the reader take note: the narrator will not tell lies! | |||

While the ''narrator'' pretends to believe his lie, it is not always easy to ascertain what the ''listener’s'' response was supposed to be. Was he to take seriously the tale about a mute man giving information, a naked person putting a millstone in his pocket? And was he really intended to believe the stories about Cockaigne, with its cakes hanging from trees, its animals defecating gold, its rejuvenating river? Such stories have been taken to make no claim to anything but entertainment, or alternatively, to satirize man’s greed. On the other hand, it has been assumed that these texts functioned in a context where nothing was deemed impossible: any wish, if cherished in earnest, was capable of fulfilment.<ref>Kalff 1972[1884]:491, 493</ref> Riddle, lie and wish are closely related here. | |||

====German==== | |||

An early German example, ''Sō ist diz von Lügenen'', dates from the fourteenth century, and once again, the lie is explicit: the title announces that this is a book about lies. Later stories deal with ''Schlaraffenland'' (a counterpart to Cockaigne), while a compilation of popular lore was published as ''Der edle Finkenritter'' (1559). H.W. Kirchhof’s ''Wendunmut'' (1563) relates fantastic adventures. Raspe’s ''[[Baron Münchhausen|Munchausen]]'' (1785) was long thought to be German, but its author had in fact fled to England and wrote his famous narrative in English.<ref>Meertens 1982:328-29</ref> | |||

====French==== | |||

The French name for such false stories was ''contes-menteries'', and a number of these were collected in ''Nouvelle fabrique des excellents traits de vérité'' (1579). Here, too, the title claims that the stories are true. A Swiss literary narrative by Rodolphe Töpffer is the ''Histoire de M. Cryptogame'' (1846).<ref>Meertens 1982:328-29</ref> | |||

==Themes and motifs== | |||

Unlike the deliberate lies recounted in more or less literary forms by [[Poggio Bracciolini|Poggio]], Raspe, Töpffer, Mark Twain and others, popular tradition is subject to decay, which makes it impossible to ascertain the provenance of many mendacious tales. There is, in addition, little doubt that early editions have been lost.<ref>F.P. Wilson, “The English Jest-Books of the Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries”, in: ''Shakespearian and Other Studies'', Oxford 1970[1969]:285-324</ref> The origins and continuity of tales which have been handed down in extant collections are often impossible to trace. But certain motifs and themes recur. | |||

*''Cockaigne''<br>The theme of the land bountiful is international. It may be called "Kurrelmurre" in German; "Luilekkerland" (“the land of easy and delight”) in Dutch; "Cuccagna", "Coquaingne" or Cockaygne" in Sicilian, French and English<ref>Kalff 1972[1884]:489;<br>Meertens 1982:328-29;<br>P. de Keyser, “De nieuwe reis naar Luilekkerland”, in: P. de Keyser (ed.), ''Ars Folklorica Belgica. Noord- en Zuid-Nederlandse volkskunst''. Antwerpen/Amsterdam, 1956:7-41</ref>, but the theme remains the same. The story of this Paradise on earth, fulfilling all man’s wishes and thus depicting his greed, is utopia and satire at the same time.<ref>De Keyser 1956:14</ref> Varieties occur; thus, the delicacies hanging from trees vary with the tastes of the audience, but delicacies they are, and in all cases they are freely available. There are Italian, French and English versions, and the story seems to have its roots in Antiquity.<ref>Meertens 1982:328-29</ref> | |||

*''The world inverted''<br>Medieval carnival celebrations were characterized by an inversion of values. A commoner became a prince for a very short time, local authority lay low. The same motif of inversion is found in mendacious stories: a boor outwits Solomon<ref>Wilson 1982:328-29</ref>, the quarry chases the hunter. | |||

* ''Nobody''<br>In Dutch and French stories, there occurs a non-existent hero or saint called “St Nobody” or “Seigneur Nemo” (“nemo” being Latin for “nobody”). | |||

* ''The paradoxical handicap''<br>The blind man seeing, the crippled person swimming or running, the nude man pocketing a stone, are all paradoxes which may be related to the tradition of riddles.<ref>Kalff 1972[1884]:488</ref> | |||

*''The tailless beast''<br>A recurring motif is the tailless beast; a traveler rides a donkey suffering from this defect.<ref>Meertens 1982:328-29</ref> | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{reflist|2}} | {{reflist|2}} | ||

[[Category:Suggestion Bot Tag]] | |||

Latest revision as of 16:01, 24 October 2024

A tall-tale postcard based on a photomontage, illustrating the kind of exaggeration typical for tall tales: A dwarf drives a cart, drawn by a mule, filled with giant eggs. The dwarf is wearing a suit and a top hat. The mule is being confronted on the road by a giant chicken.

A tall tale is a narrative, song or jest that depicts exaggerated situations, incredible boasts or impossible achievements. In a narrow sense, the term applies to stories told by American frontiersmen, and indeed the term itself originates from the mid-1800s.[1] In a wider sense, however, a tall tale is a specimen of mendacious literature, often a folk narrative, whether or not recorded in writing. Written forms, however, also exist as literary creations in their own right. As such, the genre is considered to be universal and of all ages.[2]

Tall tales are not just fictitious, they are patently impossible. If the tall tale is a first-person narrative, the narrator pretends to believe his own story,[3] while in third-person narratives, the account is likewise presented as true. It is a characteristic of the tall tale that it is told by a liar, not by a fallible narrator. While delimitations are difficult to draw sharply, tall tales should therefore be distinguished from fables (which characteristically present a moral) and from science fiction or science fantasy (which by its very nature presents itself as a fantasy).

The American tradition

Tall tales in the American folk tale tradition often snowball round such well-known figures as Bill Cody and Davy Crockett. But there is also a New England tradition, including the tale of Captain Stormalong, who, caught in a storm, steered his ship through the Panama Isthmus, thus digging the canal. Apart from the oral tradition, there are literary specimens by Washington Irving (History of New York, 1809) and Mark Twain (Life on the Mississippi, 1883).[4]

A discontinuous history: mendacious literature

Non-Western traditions

Because lies are of all ages, mendacious literature, whether oral or written, has had a long tradition and seems to occur all over the world. Certain themes recur internationally. Mendacious stories in other cultures include those in the One thousand and One Nights, while they are also found in the Talmud.[5]

The Western tradition

In Western Europe, the precursor is Lucian of Samosata, who lived in the second century, and whose account of his sea voyage is packed with marvels. Of much later date is the eleventh-century Modus florum, where the lie is explicit: by telling mendacious stories, the protagonist is accepted as suitor to the king’s daughter.[6]

Riddles, lies, and wishes

Mendacious songs from the Middle Ages have been handed down in song books. They occupy a position in between other fantastic genres, such as riddles and wish-fulfilment songs. Riddles may depict the impossible or the seemingly impossible. Thus, a bird without wings is a recurring motif, but in certain contexts, it is revealed to stand for something else: it may then be a metaphor for a snowflake. By contrast, an actual impossibility is postulated in a sixteenth-century German song, where a young man undertakes to marry a fair maid if she proves capable of weaving silk from straw.[7]

The lie may be presented as a dream: in one of these songs, the narrator rides a three-legged ox around the world, but while he acknowledges that this is something he has dreamt, let the reader take note: the narrator will not tell lies!

While the narrator pretends to believe his lie, it is not always easy to ascertain what the listener’s response was supposed to be. Was he to take seriously the tale about a mute man giving information, a naked person putting a millstone in his pocket? And was he really intended to believe the stories about Cockaigne, with its cakes hanging from trees, its animals defecating gold, its rejuvenating river? Such stories have been taken to make no claim to anything but entertainment, or alternatively, to satirize man’s greed. On the other hand, it has been assumed that these texts functioned in a context where nothing was deemed impossible: any wish, if cherished in earnest, was capable of fulfilment.[8] Riddle, lie and wish are closely related here.

German

An early German example, Sō ist diz von Lügenen, dates from the fourteenth century, and once again, the lie is explicit: the title announces that this is a book about lies. Later stories deal with Schlaraffenland (a counterpart to Cockaigne), while a compilation of popular lore was published as Der edle Finkenritter (1559). H.W. Kirchhof’s Wendunmut (1563) relates fantastic adventures. Raspe’s Munchausen (1785) was long thought to be German, but its author had in fact fled to England and wrote his famous narrative in English.[9]

French

The French name for such false stories was contes-menteries, and a number of these were collected in Nouvelle fabrique des excellents traits de vérité (1579). Here, too, the title claims that the stories are true. A Swiss literary narrative by Rodolphe Töpffer is the Histoire de M. Cryptogame (1846).[10]

Themes and motifs

Unlike the deliberate lies recounted in more or less literary forms by Poggio, Raspe, Töpffer, Mark Twain and others, popular tradition is subject to decay, which makes it impossible to ascertain the provenance of many mendacious tales. There is, in addition, little doubt that early editions have been lost.[11] The origins and continuity of tales which have been handed down in extant collections are often impossible to trace. But certain motifs and themes recur.

- Cockaigne

The theme of the land bountiful is international. It may be called "Kurrelmurre" in German; "Luilekkerland" (“the land of easy and delight”) in Dutch; "Cuccagna", "Coquaingne" or Cockaygne" in Sicilian, French and English[12], but the theme remains the same. The story of this Paradise on earth, fulfilling all man’s wishes and thus depicting his greed, is utopia and satire at the same time.[13] Varieties occur; thus, the delicacies hanging from trees vary with the tastes of the audience, but delicacies they are, and in all cases they are freely available. There are Italian, French and English versions, and the story seems to have its roots in Antiquity.[14]

- The world inverted

Medieval carnival celebrations were characterized by an inversion of values. A commoner became a prince for a very short time, local authority lay low. The same motif of inversion is found in mendacious stories: a boor outwits Solomon[15], the quarry chases the hunter.

- Nobody

In Dutch and French stories, there occurs a non-existent hero or saint called “St Nobody” or “Seigneur Nemo” (“nemo” being Latin for “nobody”).

- The paradoxical handicap

The blind man seeing, the crippled person swimming or running, the nude man pocketing a stone, are all paradoxes which may be related to the tradition of riddles.[16]

- The tailless beast

A recurring motif is the tailless beast; a traveler rides a donkey suffering from this defect.[17]

References

- ↑ SOED s.v. “tall II".

- ↑ P.J. Meertens, “Leugenliteratuur”, in: A.G.H. Bachrach et al., Moderne Encyclopedie van de Wereldliteratuur , vol. 5. Haarlem/Antwerpen 1982:328-29

- ↑ Meertens 1982:328-29

- ↑ Merriam Webster’s Encyclopedia of Literature, Springfield 1995 s.v. “tall tale”

- ↑ Meertens 1982:328-29

- ↑ Meertens 1982:328-29

- ↑ G. Kalff, ‘’Het lied in de middeleeuwen’’, Ch. IV, “Raadsel-, Leugen en Wenschliederen”. Arnhem 1972[1884]:486-93, (online version [1] accessed Mar. 9, 2010)

- ↑ Kalff 1972[1884]:491, 493

- ↑ Meertens 1982:328-29

- ↑ Meertens 1982:328-29

- ↑ F.P. Wilson, “The English Jest-Books of the Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries”, in: Shakespearian and Other Studies, Oxford 1970[1969]:285-324

- ↑ Kalff 1972[1884]:489;

Meertens 1982:328-29;

P. de Keyser, “De nieuwe reis naar Luilekkerland”, in: P. de Keyser (ed.), Ars Folklorica Belgica. Noord- en Zuid-Nederlandse volkskunst. Antwerpen/Amsterdam, 1956:7-41 - ↑ De Keyser 1956:14

- ↑ Meertens 1982:328-29

- ↑ Wilson 1982:328-29

- ↑ Kalff 1972[1884]:488

- ↑ Meertens 1982:328-29