User:Loc Vu-Quoc/Draft:Nguyen Ngoc Bich: Difference between revisions

Loc Vu-Quoc (talk | contribs) (→Ho Chi Minh: updated) |

Loc Vu-Quoc (talk | contribs) (→Ho Chi Minh: updated) |

||

| (21 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

[[User:Loc_Vu-Quoc/Draft:Nguyen_Ngoc_Bich]] | [[User:Loc_Vu-Quoc/Draft:Nguyen_Ngoc_Bich]] | ||

--------------- | --------------- | ||

<!-- | <!-- | ||

<span style="font-size:250%; color:blue">"HELLO"</span> | <span style="font-size:250%; color:blue">"HELLO"</span> | ||

[[User:Loc Vu-Quoc|Loc Vu-Quoc]] | [[User:Loc Vu-Quoc|Loc Vu-Quoc]] | ||

--> | --> | ||

By [[User:Loc Vu-Quoc|Loc Vu-Quoc]] ([https://archive.is/YUGPb Archive.is 2024.10.27]), [https://citizendium.org/wiki/index.php?title=Nguyen_Ngoc_Bich&action=history Edit history] ◉ | By [[User:Loc Vu-Quoc|Loc Vu-Quoc]] ([https://archive.is/YUGPb Archive.is 2024.10.27]), [https://citizendium.org/wiki/index.php?title=Nguyen_Ngoc_Bich&action=history Edit history] ◉ | ||

Started at [https://citizendium.org/wiki/index.php?title=Nguyen_Ngoc_Bich&oldid=893049 08:10, 10 June 2023] | Started at [https://citizendium.org/wiki/index.php?title=Nguyen_Ngoc_Bich&oldid=893049 08:10, 10 June 2023] | ||

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

highly influential book titled ''The Struggle for Indochina''<!--{{sfn|Hammer|1954}}--><ref name="Hammer.1954"/> <sup>[[#Hammer (1954) |N.ehb]]</sup><span id="Hammer (1954) jump"></span> | highly influential book titled ''The Struggle for Indochina''<!--{{sfn|Hammer|1954}}--><ref name="Hammer.1954"/> <sup>[[#Hammer (1954) |N.ehb]]</sup><span id="Hammer (1954) jump"></span> | ||

<!--{{em dash}}-->---published in 1954 well before the United States sent American troops to Vietnam in the 1960s<!--{{em dash}}-->---described the events, politics, and historic personalities leading to the [[Wikipedia:First Indochina War|First Indochina War]]. Her works were considered among the must-read books by respected historians on Vietnam history, as Osborne (1967)<!--{{sfn|Osborne|1967}}--><ref name="Osborne.1967"/> wrote: "Indeed, any serious student of Viet-Nam will have either read Devillers,<sup>[[#Devillers ref |N.pd]]</sup><span id="Devillers ref jump"></span> | <!--{{em dash}}-->---published in 1954 well before the United States sent American troops to Vietnam in the 1960s<!--{{em dash}}-->---described the events, politics, and historic personalities leading to the [[Wikipedia:First Indochina War|First Indochina War]]. Her works were considered among the must-read books by respected historians on Vietnam history, as Osborne (1967)<!--{{sfn|Osborne|1967}}--><ref name="Osborne.1967"/> wrote: "Indeed, any serious student of Viet-Nam will have either read Devillers,<sup>[[#Devillers ref |N.pd]]</sup><span id="Devillers ref jump"></span> | ||

[[Wikipedia:Jean Lacouture|Lacouture]], [[Wikipedia:Bernard B. Fall|Fall]], [[Wikipedia:Ellen Hammer| | [[Wikipedia:Jean Lacouture|Lacouture]],<sup>[[#Jean Lacouture spoke |N.jls]]</sup><span id="Jean Lacouture spoke jump"></span> [[Wikipedia:Bernard B. Fall|Fall]], [[Wikipedia:Ellen Hammer|Hammer]] and Lancaster's<ref name=Lancaster.1961/> | ||

<sup>[[#Lancaster book |N.dlb]]</sup><span id="Lancaster book jump"></span> | <sup>[[#Lancaster book |N.dlb]]</sup><span id="Lancaster book jump"></span> | ||

studies already, or will be better served by reading them first hand." To give a historical context within which [[Nguyen Ngoc Bich|Bich]] fought the French colonists, there is no better English source to begin than Dr. Hammer's Vietnam-history book. | studies already, or will be better served by reading them first hand." To give a historical context within which [[Nguyen Ngoc Bich|Bich]] fought the French colonists, there is no better English source to begin than Dr. Hammer's Vietnam-history book. | ||

| Line 155: | Line 155: | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

The Southeast Asia and Buddhism expert [[Wikipedia:Paul Mus|Paul Mus]], who first met [[Wikipedia:Ho Chi Minh|Ho Chi Minh]] in 1945, recounted that [[Wikipedia:Ho Chi Minh|Ho Chi Minh]] said<ref name="NYT Paul Mus obituary"/ | The Southeast Asia and Buddhism expert [[Wikipedia:Paul Mus|Paul Mus]], who first met [[Wikipedia:Ho Chi Minh|Ho Chi Minh]] in 1945, recounted that [[Wikipedia:Ho Chi Minh|Ho Chi Minh]] said<ref name="NYT Paul Mus obituary"/> then:<sup>[[#Year of the Pig|N.ytp1]]</sup><span id="Year of the Pig jump1"></span> | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

{| cellpadding=0 cellspacing=0 | {| cellpadding=0 cellspacing=0 | ||

| Line 296: | Line 292: | ||

<!--{{Image|Ho Chi Minh observing battle 1950 Sep.JPG|right|350px|Add image caption here.}}--> | <!--{{Image|Ho Chi Minh observing battle 1950 Sep.JPG|right|350px|Add image caption here.}}--> | ||

[[File:Ho Chi Minh observing battle 1950 Sep.JPG|thumb|left|250px|Ho Chi Minh observing a battlefield in 1950 Sep.]] | [[File:Ho Chi Minh observing battle 1950 Sep.JPG|thumb|left|250px|Ho Chi Minh observing a battlefield in 1950 Sep.]] | ||

In May 1946, Ho Chi Minh boarded an airplane for France.<sup>[[#Ho in France 1946 |N.hif]]</sup><span id="Ho in France 1946 jump"></span> The conference at Fontainebleau, outside of Paris, failed to reach an agreement. | In May 1946, Ho Chi Minh boarded an airplane for France.<sup>[[#Ho in France 1946 |N.hif]]</sup><span id="Ho in France 1946 jump"></span> The conference at Fontainebleau, outside of Paris, failed to reach an agreement. With "nearly insoluble fundamental differences of viewpoint,"<ref name=Sainteny.1972/><sup>:84</sup> the main disagreements centered around the unification of the three regions, called the "three Ky," namely Tonkin (north), Annam (central), Cochin China (south Vietnam), and the independence of Vietnam, to which France only wanted to give an "autonomy."<ref name=Sainteny.1972/><sup>:84</sup> On 1946 August 1, D'Argenlieu undercut the Fontaineblau negotiation by calling for a "federation" conference in Dalat, giving the autonomy status to Cochin China, thus preempted the possibility of Cochin China to join a unification of the "three Ky" via a referendum as agreed to in the March 6 Accords.<ref name=Sainteny.1972/><sup>:84</sup> Ho told Sainteny: | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

{| cellpadding=0 cellspacing=0 | {| cellpadding=0 cellspacing=0 | ||

| Line 463: | Line 459: | ||

=== War began === | === War began === | ||

Two camps of historians chose two different dates for the start of the First Indochina War: Either 1945 Sep 23, or more than a year later, 1946 Dec 19. Of these two dates, 1945 Sep 23 is more relevant to [[Nguyen Ngoc Bich|Bich]] since he had been captured on 1946 Aug 25,<ref name=NNC.VQL.2023/> before 1946 Dec 19. | Two camps of historians chose two different dates for the start of the First Indochina War: Either 1945 Sep 23 (one year ''before'' the failed Fontainebleau conference in 1946 Sep), or more than a year later, 1946 Dec 19 (three months ''after'' the failed Fontainebleau conference in 1946 Sep). Of these two dates, 1945 Sep 23 is more relevant to [[Nguyen Ngoc Bich|Bich]] since he had been captured on 1946 Aug 25,<ref name=NNC.VQL.2023/> before 1946 Dec 19. | ||

==== 1945 Sep 23 ==== | ==== 1945 Sep 23, Cochin China ==== | ||

The First Indochina War started on 1945 September 23 with the brutal repression of the Vietnamese by some 1,400 French soldiers, who had been imprisoned by the Japanese, then freed and re-armed by British General Gracey, and who went on a rampage, beating, lynching any Vietnamese they saw on the street.<!--{{sfn|Logevall|2012|p=115}}--><ref name=Logevall.2012/><sup>:115</sup> | The First Indochina War started on 1945 September 23 in Cochin China (south Vietnam) with the brutal repression of the Vietnamese by some 1,400 French soldiers, who had been imprisoned by the Japanese, then freed and re-armed by British General Gracey, and who went on a rampage, beating, lynching any Vietnamese they saw on the street.<!--{{sfn|Logevall|2012|p=115}}--><ref name=Logevall.2012/><sup>:115</sup> | ||

French war correspondent Germaine Krull, who arrived in Saigon on 1945 Sep 12 with the British Gurkhas soldiers and a small group of French soldiers,<sup>[[#British-French arrived |N.bfa]]</sup><span id="British-French arrived jump"></span> was likely the first to mark the start of the First Indochina War on this date, as she described in her "most graphic, vivid, and absorbing" report<sup>[[#Moffat memo on Krull |N.mok]]</sup><span id="Moffat memo on Krull jump"></span> what she had witnessed "with her own eyes": | French war correspondent Germaine Krull, who arrived in Saigon on 1945 Sep 12 with the British Gurkhas soldiers and a small group of French soldiers,<sup>[[#British-French arrived |N.bfa]]</sup><span id="British-French arrived jump"></span> was likely the first to mark the start of the First Indochina War on this date, as she described in her "most graphic, vivid, and absorbing" report<sup>[[#Moffat memo on Krull |N.mok]]</sup><span id="Moffat memo on Krull jump"></span> what she had witnessed "with her own eyes": | ||

| Line 484: | Line 480: | ||

|} | |} | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

{| class="wikitable style="text-align: center;" | |||

|- | |||

! French colonists tied up a Vietnamese, choked him, pulled his hair, and threw him onto a military truck | |||

|- | |||

| <gallery mode=packed widths="260" heights="100"> | |||

File:French tied up, choked Vietnamese - 1450.JPG|Video time [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0pibqRPi8Bo&t=14m50s 14:50]. | |||

File:French tied up, choked Vietnamese - 1453.JPG|Video time [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0pibqRPi8Bo&t=14m52s 14:52]. | |||

File:French tied up, choked Vietnamese - 1456.JPG|Video time [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0pibqRPi8Bo&t=14m55s 14:55]. | |||

File:French tied up, choked Vietnamese - 1455.JPG|Video time [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0pibqRPi8Bo&t=15m00s 15:00]. | |||

File:French tied up, choked Vietnamese - 1500.JPG|Video time [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0pibqRPi8Bo&t=15m01s 15:01]. | |||

</gallery> | |||

|- | |||

| style="text-align: left;" | In the 1968 Documentary [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0pibqRPi8Bo In the Year of the Pig], time [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0pibqRPi8Bo&t=14m38s 14:38], [[Wikipedia:David Halberstam|David Halberstam]] said: "... the Indochina war and all the best and most talented Vietnamese of a generation had faced, in 1946 and 1947, the alternative of the French or the Viet Minh. The best of a generation, the kind of young men who would join up the day after Pearl Harbor in this country [United States]. Are you going to fight to kick out the French, or are you going to be a French puppet? So the most talented people of a generation all signed up and the Viet Minh won this war and it was an enormously popular national war." | |||

|} | |||

This date, 1945 Sep 23, "would go down in history: [[Wikipedia:vi:Trần_Văn_Giàu|Trần Văn Giàu]], | This date, 1945 Sep 23, "would go down in history: [[Wikipedia:vi:Trần_Văn_Giàu|Trần Văn Giàu]], | ||

| Line 563: | Line 574: | ||

* Quotations from Tønnesson (2010){{sfn|Tønnesson|2010}} and Donaldson (1996){{sfn|Donaldson|1996}} | * Quotations from Tønnesson (2010){{sfn|Tønnesson|2010}} and Donaldson (1996){{sfn|Donaldson|1996}} | ||

==== 1946 Dec 19 ==== | ==== 1946 Dec 19, Tonkin ==== | ||

=== Resistance === | === Resistance === | ||

| Line 841: | Line 852: | ||

<span id="Devillers ref"></span> | <span id="Devillers ref"></span> | ||

* (↑ [[#Devillers ref jump |N.pd]]) <i>(Philippe) Devillers:</i> See <!--[[w:French_Cochinchina#cite_note-41|French Cochinchina, Ref. 40]] | * (↑ [[#Devillers ref jump |N.pd]]) <i>(Philippe) Devillers:</i> See <!--[[w:French_Cochinchina#cite_note-41|French Cochinchina, Ref. 40]] | ||

--> [https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=French_Cochinchina&oldid=1247806900#cite_note-43 French Cochinchina, version 03:16, 26 September 2024, Ref.42]: Philippe Devillers, ''Histoire du Viêt-Nam de 1940 à 1952'', Seuil, 1952, and [https://indomemoires.hypotheses.org/21651 Philippe Devillers (1920–2016), un secret nommé Viêt-Nam, Mémoires d'Indochine], [https://web.archive.org/web/20220629093316/https://indomemoires.hypotheses.org/21651 Internet archived 2022.06.29]. | --> [https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=French_Cochinchina&oldid=1247806900#cite_note-43 French Cochinchina, version 03:16, 26 September 2024, Ref.42]: Philippe Devillers, ''Histoire du Viêt-Nam de 1940 à 1952'', Seuil, 1952, and [https://indomemoires.hypotheses.org/21651 Philippe Devillers (1920–2016), un secret nommé Viêt-Nam, Mémoires d'Indochine], [https://web.archive.org/web/20220629093316/https://indomemoires.hypotheses.org/21651 Internet archived 2022.06.29]. See Devillers speaking in an interview in the 1968 documentary ''In the Year of the Pig'' at video time [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0pibqRPi8Bo&t=5m58s 5:58]. | ||

<!--<sup>[[#Devillers incorrect info |N.dii]]</sup><span id="Devillers incorrect info jump"></span>--> | <!--<sup>[[#Devillers incorrect info |N.dii]]</sup><span id="Devillers incorrect info jump"></span>--> | ||

| Line 901: | Line 912: | ||

<!--{{Image|Ho Chi Minh and Sainteny on Catalina 1945 Mar 24.JPG|right|350px|Add image caption here.}}--> | <!--{{Image|Ho Chi Minh and Sainteny on Catalina 1945 Mar 24.JPG|right|350px|Add image caption here.}}--> | ||

[[File:Ho Chi Minh and Sainteny on Catalina 1945 Mar 24.JPG|thumb|right|150px|Ho Chi Minh and Sainteny on the seaplane ''Catalina,'' on their way to meet d'Argenlieu on the battleship ''Emile-Bertin'', | [[File:Ho Chi Minh and Sainteny on Catalina 1945 Mar 24.JPG|thumb|right|150px|Ho Chi Minh and Sainteny on the seaplane ''Catalina,'' on their way to meet d'Argenlieu on the battleship ''Emile-Bertin'', 1946 Mar 24.]] | ||

<!--<sup>[[#HCM Sainteny Catalina |N.hsc]]</sup><span id="HCM Sainteny Catalina jump"></span>--> | <!--<sup>[[#HCM Sainteny Catalina |N.hsc]]</sup><span id="HCM Sainteny Catalina jump"></span>--> | ||

<span id="HCM Sainteny Catalina"></span> | <span id="HCM Sainteny Catalina"></span> | ||

* (↑ [[#HCM Sainteny Catalina jump |N.hsc]]) <i>Ho and Sainteny on Catalina:</i> On | * (↑ [[#HCM Sainteny Catalina jump |N.hsc]]) <i>Ho and Sainteny on Catalina:</i> On 1946 Mar 24, Ho and Jean Saiteny boarded the seaplane ''Catalina'' that took them to meet Admiral Thierry d'Argenlieu on the French battleship ''Emile-Bertin,'' mooring in the Ha Long Bay. | ||

<!--<sup>[[#Ho in France 1946 |N.hif]]</sup><span id="Ho in France 1946 jump"></span>--> | <!--<sup>[[#Ho in France 1946 |N.hif]]</sup><span id="Ho in France 1946 jump"></span>--> | ||

| Line 931: | Line 942: | ||

* (↑ [[#HCM Vietnam Independence jump |N.hvi]]) <i>HCM Vietnam Independence :</i> For a detailed comparative analysis between the US Declaration of Independence and Ho Chi Minh’s Declaration of Vietnam Independence, see ''Notes of Vietnam History''.<ref name=VQL.2023a/> "Bao Dai, the French-protected emperor of Annam, with nominal authority also in Tonkin, had gained nominal independence aer Japan ousted the French regime in March 1945. When he abdicated voluntarily in August 1945, he ceded his powers to the new Democratic Republic. Shortly before Bao Dai abdicated, his government had obtained from Japan something that France had always refused to concede: sovereignty also in Nam Ky (Cochinchina), hitherto under direct French rule, where the emperor had previously had no say." <ref name=Tonnesson.2010/><sup>:12</sup> | * (↑ [[#HCM Vietnam Independence jump |N.hvi]]) <i>HCM Vietnam Independence :</i> For a detailed comparative analysis between the US Declaration of Independence and Ho Chi Minh’s Declaration of Vietnam Independence, see ''Notes of Vietnam History''.<ref name=VQL.2023a/> "Bao Dai, the French-protected emperor of Annam, with nominal authority also in Tonkin, had gained nominal independence aer Japan ousted the French regime in March 1945. When he abdicated voluntarily in August 1945, he ceded his powers to the new Democratic Republic. Shortly before Bao Dai abdicated, his government had obtained from Japan something that France had always refused to concede: sovereignty also in Nam Ky (Cochinchina), hitherto under direct French rule, where the emperor had previously had no say." <ref name=Tonnesson.2010/><sup>:12</sup> | ||

<!--<sup>[[#Jean Lacouture spoke |N.jls]]</sup><span id="Jean Lacouture spoke jump"></span>--> | |||

<span id="Jean Lacouture spoke"></span> | |||

* (↑ [[#Jean Lacouture spoke jump |N.jls]]) <i>(Jean) Lacouture spoke:</i> See Lacouture speaking about Ho Chi Minh in the 1968 documentary ''In the Year of the Pig'' at video time [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0pibqRPi8Bo&t=8m11s 8:11]. | |||

<!--<sup>[[#Lancaster book |N.dlb]]</sup><span id="Lancaster book jump"></span>--> | <!--<sup>[[#Lancaster book |N.dlb]]</sup><span id="Lancaster book jump"></span>--> | ||

<span id="Lancaster book"></span> | <span id="Lancaster book"></span> | ||

| Line 1,041: | Line 1,056: | ||

<!--<sup>[[#Year of the Pig|N.ytp]]</sup><span id="Year of the Pig jump"></span>--> | <!--<sup>[[#Year of the Pig|N.ytp]]</sup><span id="Year of the Pig jump"></span>--> | ||

<span id="Year of the Pig"></span> | <span id="Year of the Pig"></span> | ||

* (↑ [[#Year of the Pig jump1|N.ytp1]], [[#Year of the Pig jump2|N.ytp2]]) <i>Year of the Pig:</i> In his interview in the 1968 documentary ''[[Wikipedia:In the Year of the Pig|In the Year of the Pig]],'' at the [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0pibqRPi8Bo&t= | * (↑ [[#Year of the Pig jump1|N.ytp1]], [[#Year of the Pig jump2|N.ytp2]]) <i>Year of the Pig:</i> In his interview in the 1968 documentary ''[[Wikipedia:In the Year of the Pig|In the Year of the Pig]],'' Paul Mus, whom High Commissioner d'Argenlieu sent to meet Ho Chi Minh in Hanoi at the end of 1945 (video time [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0pibqRPi8Bo&t=12m17s 12:17]) recounted (time [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0pibqRPi8Bo&t=13m56s 13:56]): "[[Wikipedia:Ho Chi Minh|Ho Chi Minh]] said [in 1945], 'I have no army.' That's not true now [in 1968]. 'I have no army.' 1945. 'I have no finance. I have no diplomacy. I have no public instruction. I have just hatred and I will not disarm it until you give me confidence in you.' Now this is the thing on which I would insist because it's still alive in his memory, as in mine. For every time [[Wikipedia:Ho Chi Minh|Ho Chi Minh]] has trusted us, we betrayed him." See also a 2016 review<ref name=Browder.2016/> of this 1968 documentary ''[[Wikipedia:In the Year of the Pig|In the Year of the Pig]].'' | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

| Line 1,122: | Line 1,137: | ||

[https://web.archive.org/web/20230328065158/https://www.britannica.com/question/How-many-people-died-in-the-Vietnam-War Internet archived on 2023.03.28]. | [https://web.archive.org/web/20230328065158/https://www.britannica.com/question/How-many-people-died-in-the-Vietnam-War Internet archived on 2023.03.28]. | ||

--> | --> | ||

</ref> | |||

<ref name=Browder.2016> | |||

{{cite book | |||

|last=Browder | |||

|first=Laura | |||

|chapter=The Meaning of the Soldier: ''In the Year of the Pig'' and ''Hearts and Minds'' | |||

|title=A Companion to the War Film | |||

|date= May 1, 2016 | |||

|pages=356–370 |doi=10.1002/9781118337653.ch21 | |||

|url=https://scholarship.richmond.edu/english-faculty-publications/172/ | |||

|archive-url=http://web.archive.org/web/20240604151647/https://scholarship.richmond.edu/english-faculty-publications/172/ | |||

|archive-date=2024-06-04 | |||

}} | |||

[http://web.archive.org/web/20240604151647/https://scholarship.richmond.edu/english-faculty-publications/172/ Internet Archive 2024.06.04] | |||

</ref> | </ref> | ||

Revision as of 17:41, 1 December 2024

User:Loc_Vu-Quoc/Draft:Nguyen_Ngoc_Bich

By Loc Vu-Quoc (Archive.is 2024.10.27), Edit history ◉ Started at 08:10, 10 June 2023

Introduction

| Nguyễn Ngọc Bích | |

|---|---|

| Born | 18 May 1911 Bến Tre, Vietnam |

| Died | 4 Dec 1966 Thủ Đức, Vietnam |

| Occupation | *Engineer

|

| Title | Doctor (medical) |

| Known for | Resistance war, politics |

Nguyễn Ngọc Bích (1911–1966) is a hero of the Vietnamese resistance against the French colonists[1]:850. NOTE N.psq1 and revered as one of the most popular local heroes.[2]:122 The Nguyen-Ngoc-Bich street in the city of Cần Thơ, Vietnam, was named after him to honor and commemorate his feats (of sabotaging bridges to slow down the colonial French-army advances) and heroism (being on the French most-wanted list,[2]:122 imprisoned, subjected to an "intensive and unpleasant interrogation"[2]:122 that left a mark on his forehead,N.bi1 and exiled) during the First Indochina War.

A French-educated engineer and medical doctor, and an intellectual and politician, he proposed an alternative viewpoint to avoid the high-casualty, high-cost war between North Vietnam and South Vietnam.[3]

Upon graduating from the École polytechnique (engineering military school under the French Ministry of Armed Forces) and then from the École nationale des ponts et chaussées (civil engineering) in France in 1935,[4] Dr. Bich returned to Vietnam to work for the French colonial government. After World War II, in 1945, he joined the Viet-Minh,N.bvm and became a senior commander in the Vietnamese resistance movement, and insisted on fighting for Vietnam's independence, not for communism.

SuspectingN.bs of being betrayed by the Communist factionN.bs of the Viet-Minh and apprehended by the French forces, Bich was saved from execution by a campaign for amnesty by his École polytechnique classmates based in Vietnam, mostly high-level officers of the French army,[5]: 299 and was subsequently exiled to France, where he founded with friends and managed the Vietnamese publishing house Minh Tan (in Paris), which published many important works for the Vietnamese literature,N.mbl in particular, the Sino-Vietnamese Dictionary, a key reference for many generations of writers and students for a standardized Vietnamese writing. To reprint this dictionary, Bich wrote a moving open letter to the dictionary author Dao Duy Anh, who could not be located due to war time, to ask for permission.N.vqf

In parallel, Bich studied medicine and became a medical doctor. He was highly regarded in Vietnamese politics, and was suggested by the French in 1954 as an alternative to Ngo Dinh Diem as the sixth prime minister of the State of Vietnam under the former Emperor Bao Dai as Head of State,[6]:84 who selected Ngo Dinh Diem as prime minister. While Bich's candidature for the 1961 presidential election in opposition to Diem was, however, declared invalid by the Saigon authorities at the last moment for "technical reasons",[7][4], he was "regarded by many as a possible successor to President Ngo Dinh Diem".[7] N.pi, N.tcq

A large majority of the information in this article came from the master document Nguyen Ngoc Bich (1911–1966): A Biography,[8] which contains even more information, including primary-source evidence and photos, than presented here. Most images in the present article were uploaded for the first time at the time of the writing by the original writer.N.vql

Important historical events that affected Bich's adult life, together with those mentioned in his 1962 paper (e.g., failed agrarian reform, napalm bombs, famine, conquest for rice, etc.) are summarized, in particular the atmosphere in which Bich had lived for ten years working for the French colonialists (from 1935 to 1945), and the historical conditions that drove this French-educated engineer to become a "Francophile anticolonialist"N.fa1, N.psq2 and to join the Viet-Minh in 1945N.bvm (e.g., the French brutal repressions in 1940 and 1945, the power vacuum after the Japanese coup de force in 1945, Ho Chi Minh's call for a general uprising from Tân Trào, the 1945 August Revolution, the Black Sunday on 1945 Sep 2 in Saigon, etc.). The key principle is to summarize a historical event only when it was directly related to Bich's activities. Care is exercised in selecting references and quotations that complement, but not duplicate, other Wikipedia articles at the time of this writing. For example, the history and the general use of napalm bombs, which Bich mentioned in his 1962 article, are not summarized. Regarding the French using American-made napalm bombs in the First Indochina War, well-known battlesN.nb are also not summarized.

First Indochina War

The broader historic events of World War II and the First Indochina War---specifically, the short interwar period between end of the former and the beginning of the later—led to the context in which Nguyen Ngoc Bich fought the French colonists until he was captured.

Ellen J. Hammer was the first American-born historianN.vt with a deep knowledge of the French colonial rule in Indochina in the early 1950s during the First Indochina War. Dr. Hammer's[9] N.ejh highly influential book titled The Struggle for Indochina[10] N.ehb ---published in 1954 well before the United States sent American troops to Vietnam in the 1960s---described the events, politics, and historic personalities leading to the First Indochina War. Her works were considered among the must-read books by respected historians on Vietnam history, as Osborne (1967)[11] wrote: "Indeed, any serious student of Viet-Nam will have either read Devillers,N.pd Lacouture,N.jls Fall, Hammer and Lancaster's[12] N.dlb studies already, or will be better served by reading them first hand." To give a historical context within which Bich fought the French colonists, there is no better English source to begin than Dr. Hammer's Vietnam-history book.

The American dilemma---(1) To help the French to re-establish its colony in Vietnam or (2) To help free the Vietnamese from the yoke of French colonialism---was described by Hammer as follows:

American dilemma: Help the French or help the Vietnamese ❝ The United States has entangled itself in a war in a distant corner of Asia in which it resolutely does not want to participate and from which it equally resolutely cannot abstain. It has committed itself to the cause of France [ French Indochina ] and of Bao Dai, but enough of the old spirit of anticolonialism is left to make this a somewhat unsavory commitment: it cannot bring itself wholly to ignore the fact that the free world looks less than free to a people whose country is being fought over by a foreign army. Aware that a lasting peace can be built only on satisfaction of the national aspirations of the Indochinese, the United States must at the same time conciliate a France reluctant to abandon her colonial past. ❞ ---Ellen Hammer (1954), The struggle for Indochina, Preface p. xii.[10]:xii

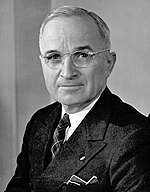

The activities directly or indirectly affected Bich's life by four historic individuals are summarized. French General de Gaulle, by his desire to reconquer Indochina as a French colony, was a main force that led to the First Indochina War, in which Bich fought. Ho Chi Minh, founder and leader of the Viet-Minh, called for the general uprising---against the French colonists and the Japanese occupiers---to which Bich responded. US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt ardent anticolonialism could have prevented the two Indochina wars, and changed the course of history. US President Harry Truman was a reason that the First Indochina War is now called the "French-American" War in Vietnamese literature,[13] and through his support for the French war effort supplied napalm bombs, which Bich mentioned in his 1962 paper. The US funded more than 30% of the war cost in 1952 under US President Eisenhouer, and "nearly 80%" in 1954 under Truman.N.fwc

Charles de Gaulle

De Gaulle was a prime mover leading to the First Indochina War in which the French-educated Bich fought on the Viet-Minh side against the French colonialists.

At the beginning of World War II, in his historic four-minute call-to-arms broadcast from London on 1940 June 18, later known as L'Appel du 18 Juin in French history, the mostly then unknownN.cdg1 General de Gaulle counted on the French Empire, with Indochina as the "Pearl of the Empire", rich in rubber, tin, coal, and rice,[14]:28 to provide resources to fight the Axis, with the support of the British Empire and the powerful industry of the United States. Understanding that Indochina was under the menace of occupation by the Japanese, de Gaulle harbored the dream of wresting this colony back into the fold of the French Empire, writing in his memoirs "As I saw her move away into the mist, I swore to myself that I would one day bring her back."[14]:25 N.dgd

On 1945 Mar 13, four days after the Japanese coup de force in Indochina (Mar 9), de Gaulle summoned US ambassador to France Jefferson Caffery[15] to complain that the French army fighting in Indochina requested help from the US military authorities in China---headed by US General Wedemeyer[16] [17]:66 who followed closely the instructions of US President Roosevelt[17]:67---but was told that "under instructions no aid could be sent."[15] De Gaulle then played the Cold-War card, telling Caffery that France would fall into the sphere of influence of the USSR if the US did not support France to retake Indochina:[18]:243

De Gaulle to Caffery, 1945 March ❝ Do you [the US] want us [France] to become... one of the federated states under the Russian aegis? The Russians are advancing apace. . . When Germany falls they will be upon us. If the public here comes to realize that you are against us in Indochina there will be terrific disappointment and nobody knows to what that will lead. We do not want to become Communist; we do not want to fall into the Russian orbit; but I hope that you do not push us into it. ❞ --- De Gaulle to Jefferson Caffery, US Ambassador to France, 1945 March[19]:289

"Within two weeks" of the death of US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt on 1945 Apr 12, de Gaulle pressured Harry Truman on the Indochina issue, and his government launched "an intensive propaganda effort to mold world opinion in favor of the status quo (French control) in Indochina",[20]:116 and this after having approved the Japanese occupation of Indochina since 1940 September 22.[20]:452 By the time General de GaulleN.cdg2 came to the US in 1945 Aug (inset photo) to campaign for US military aid from then US President Harry Truman, the "French had been forced to drown several Vietnamese uprisings in blood. They had seen the colonial economy completely disrupted. They had been humiliated by the Germans in Europe and incarcerated by the Japanese in Indochina. Even to begin to reassert sovereignty in Indochina, the French were forced to go hat in hand to the Americans (see inset photo, de Gaulle visited Truman), British, and Chinese."[21]:413

To restore French rule over Indochina, on 1945 Jun 7, as Chairman of the French Provisional Government (formed in 1944 Aug after the liberation of Paris), General de Gaulle appointed General Leclerc to establish and to command the French Expeditionary Corps.[22]:321-2 N.laa Even though Eisenhower headquarters recommended against Leclerc’s appointment in favor of General Carpentier,[23]:397 they did not follow up with this objection since the focus was on defeating Japan, but did inform the French that it would take several months to equip the French divisions.[22]:322 De Gaulle also appointed Admiral Thierry d’Argenlieu as High Commissioner of Indochina, the "French Rasputin"[20]:382 N.dar who later played a key role in sowing the seeds of the First Indochina War.

On 1945 Aug 20, just ten days before he abdicated on 1945 Aug 30,N.bda Vietnam Emperor Bao Dai sent a moving plea to de Gaulle:N.bdq

Bao Dai to de Gaulle, 1945 Aug 20 ❝ I beg you to understand that the only means of safeguarding French interests and the spiritual influence of France in Indochina is to recognize the independence of Vietnam unreservedly and to renounce any idea of reestablishing French sovereignty or rule here in any form. . . . Even if you were to reestablish the French administration here, it would not be obeyed, and each village would be a nest of resistance. . . . We would be able to understand each other so easily and become friends if you would stop hoping to become our masters again. ❞ --- Bao Dai, message to de Gaulle on 1945 Aug 20[24]:xiii–xiv

Just a few days later on 1945 Aug 26 (or very shortly thereafter), Ho Chi Minh put the resistance in much stronger terms to US OSS Major Archimedes Patti, who still remembered vividly after some 35 years:N.hcm1

Ho Chi Minh to Archimedes Patti, 1945 Aug 26 ❝ If the French intended to return to Viet Nam as imperialists to exploit, to maim and kill my people, [I] could assure them and the world that Viet Nam from north to south would be reduced to ashes, even if it meant the life of every man, woman, and child, and that [my] government's policy would be one of scorched earth to the end. ❞ --- Ho Chi Minh to OSS Maj. Archimedes Patti[20]:4

The Southeast Asia and Buddhism expert Paul Mus, who first met Ho Chi Minh in 1945, recounted that Ho Chi Minh said[25] then:N.ytp1

Ho Chi Minh to Paul Mus, 1945 ❝ I have no army, no diplomacy, no finances, no industry, no public works. All I have is hatred, and I will not disarm it until I feel I can trust you [the French]. ❞ --- Ho Chi Minh, according to Paul Mus, the New York Times 1969 obituary[25]

Paul Mus added "For every time Ho Chi Minh has trusted us, we betrayed him."N.ytp2

War broke out on 1945 Sep 23,[14]:115 with Bich joining the Viet Minh, an organization founded by Ho Chi Minh, to fight the French.

Ho Chi Minh

For thirty years, from 1912 when Ho Chi Minh first visited Boston and New York City until about 1948-1949, Ho held out his hope that the US would provide military support for his anticolonialist resistance against the French.[14]:xxii Since that visit to the US in his early twenties, Ho---like Bich, a Francophile anticolonialist,N.fa2 N.psq3 who was both a communist and a nationalistN.hcn ---developed a "lifelong admiration for Americans".[6]:55 N.haa

Seizing on the opportunity of the Japanese entering Tonkin in 1940 September[20]:452 to begin occupy Indochina (with French agreement)[20]:452 to rid Vietnam of French colonial yoke,N.hir Ho (who was in Liuzhou, China) returned to the China-Vietnam border and began a "training program for cadres".[20]:452 Then on 1941 February 8,[20]:524 Ho crossed the border to enter Vietnam for the first time after 30 years away (from 1911 to 1941), and sheltered in cave Cốc Bó[26]:73 near the Pác Bó hamlet, in the Cao Bằng province, less than a mile from the Chinese border.[14]:34 N.dii There Ho convened a plenum in 1941 May, and founded the Viet-Minh, an anticolonialist organization that Bich joined in 1945.N.bvm

On 1941 Sep 8, two months after the total integration of Indochina into the Japanese military system, Ho (still known as Nguyen Ai Quoc at that time) in his call to arm to the people of Tonkin, announced the formation of the Viet-Minh to "fight the French and Japanese fascism until the total liberation of Vietnam."[27]:97 On 1941 Oct 25, the Viet-Minh published its first manifesto:

| Viet Minh first manifesto, 1941 Oct 25 |

|---|

| ❝ Unification of all social strata, of all revolutionary organizations, of all ethnic minorities. Alliance with all other oppressed peoples of Indochina. Collaboration with all French anti-fascist groups. One goal: the destruction of colonialism and imperialist fascism. ❞ N.vmm |

In 1942 August, Ho (named "Nguyen Ai Quoc" at that time) crossed the border into China with the intention of attracting the interest of the Allies in Chungking[20]:7 (now Chongqing) for the Vietnamese resistance movement, arrested by the Chinese on 1942 August 28 for being "French spy",[20]:525 but the real reason was Ho's political activities, viewed as "Communistic", instead of "nationalistic", by the Chinese (Chiang Kai-shek) and the Allies at Chungking (now Chongqing).[27]:103 N.vnh Ho was detained for thirteen months, starting at the Tienpao prison,[20]:51 N.htp moving through eighteen different prisons,[14]:77 N.vnh2 and ending up at Liuchow[20]:46 (now Liuzhou), from where he was released on 1943 September 10, after changing his name from Nguyen Ai Quoc to Ho Chi Minh.[20]:453 At that time, the name "Nguyen Ai Quoc" was very popular, while hardly any one heard of the new name "Ho Chi Minh".N.naq

Ho Chi Minh returned to Vietnam in 1944 September, after obtaining the authorization from the Chinese authority, Gen. Chang Fa-Kwei (Zhang Fakui (German), Trương Phát Khuê (Vietnamese)) ---who was under "severe pressure from the Japanese Ichigo offensive" to obtain intelligence in Indochina---and after submitting the "Outline of the Plan for the Activities of Entering Vietnam".[22]:134 N.hvn All three protagonists---the French Vichy colonialists, the Japanese occupiers, and the Viet-Minh---were deceived by US war plan,N.uwp and expected a US invasion of Indochina.N.uii Such expectation was the main reason[22]:209 that, in 1945 February-March, during an "unusually cold month of February,"[20]:56 N.cf45 Ho once again crossed back into China, and walked from the Pác Bó hamlet to Kunming to meetN.wtk (and to "make friends with"[22]:210) American OSS and OWI (Office of War Information) officers to exchange intelligence.N.hmo [22]:238 Ho's report to the OSS mentioned the Japanese coup de force on the evening of 1945 March 9.[22]:238

In Kunming, Ho requested OSS Lt. Charles FennN.fhh to arrange for a meeting with Gen. Claire Chennault, commander of the Flying Tigers.[20]:58 In the meeting that occurred on 1945 Mar 29, Ho requested a portrait of Chennault, who signed across the bottom "Yours sincerely, Claire L. Chennault".[20]:58 Ho displayed the portrait of Chennault, along with those of Lenin and Mao, in his lodging at Tân Trào as "tangible evidence to convince skeptical Vietnamese nationalists that he had American support".[20]:58 As additional evidence, Ho also possessed six brand-new US Colt .45 pistols in original wrappings that he requested and got from Charles Fenn.[28]:79 [29]:158 This "seemingly insignificant quantity" of arms,N.hgp together with "Chennault's autographed photograph" as evidence, convinced other factions of the primacy of the Viet Minh. Ho's American-backing ruse worked.[20]:58

In Cochin China (the south),N.tcc where Bich lived and worked, Tran Van Giau (Trần Văn Giàu in Vietnamese), a Viet Minh leader and "Ho Chi Minh's trusted friend",[20]:186 on 1945 Aug 22 used Ho's ruse of "American backing for the Viet Minh", to convince other pro-Japanese nationalist groups (Phuc Quoc, Dai Viet, United National Front[20]:524) and religious sects (Cao Dai, Hoa Hao) that they would be outlawed by the invading Allies, and thus should accept the leadership of the Viet Minh, which had strong support of "the Allies with arms, equipment and training".[20]:186

Fearing a US invasion with the French colonialists helping, the Japanese initiated operation Bright Moon (Meigo sakusen), leading to a coup de force on 1945 March 9 to neutralize the French forces and to remove the French colonial administration in Indochina[17]:65 (and thus the status of Bich's job in the French colonial government).

Two days later, on 1945 Mar 11, then Emperor Bao Dai abolished the "French-Annamite Treaty of Protectorate of 1884"[20]:73 that put Vietnam under French protectorate, and proclaimed Vietnam independence:N.vnh3

Bao Dai's proclamation of Vietnam independence, 1945 Mar 11 ❝ In view of the world situation, and that of Asia in particular, the Government of Viet-Nam publicly proclaims that from this day forward, the protectorate treaty with France is abolished and that the Country resumes its rights to independence. ❝ Viet-Nam will strive using its own means to develop itself to deserve the condition of an independent State and will follow the directives of the Greater East Asia Manifesto, considering itself as a member of the Greater East Asia, to contribute its resources to the common prosperity. Therefore, the Government of Viet-Nam trusts in the loyalty of Japan and is determined to collaborate with this country to achieve the aforementioned goal. ❞

--- Bao Dai, Hue, the 27th day of the 1st month of the 20th year Bao Dai (1945 Mar 11).[27]:125

The resulting power vacuum[17]:64 following this coup de force changed the political situation, and provided a favorable setting for the Viet Minh takeover of the government.[17]:73 In 1945 April, Ho walked a perilous journey from Pác Bó to Tân Trào, the Viet Minh headquarters in the Liberated Area. There, on 1945 August 16, Ho called for a general uprising to throw out the Japanese occupiers that ultimately led to the August Revolution.N.pvar

Power vacuum yielded a bloodless revolution, 1945 Mar 9 - Aug 26 ❝ In August and September 1945, the white-bearded Ho Chi Minh emerged as the winner of the Indochina game. All along he had expected Japan to be defeated, and he had consistently sought to tie his own movement to the United States and Nationalist China. In 1945 he was guilty of the same false assumptions as the Japanese. He expected an Allied invasion and prepared himself for assisting the invading forces. Instead he got a power vacuum and a sudden Japanese surrender. This provided him with an occasion more favorable for bloodless revolution than he could ever have imagined. He then proclaimed the republic that would later defeat both France and the United States. ❞ --- Tonnesson 2007, Franklin Roosevelt, Trusteeship and Indochina: A reassessment.[17]:73

Even though being a son of a Cao Dai pope,[30] [4] [31] N.cd Bich joined the Viet Minh in 1945,N.bjvm instead of the Cao Dai force.

Under the pressure of a "strong resolution calling for Bao Dai's abdication" by the "leftist students and faculty" in Hanoi around 1945 Aug 20[20]:185-6 and also by the Viet Minh,[20]:186 Bao Dai "voluntarily"[24]:12 abdicated to become the "Supreme Advisor"[27]:143 N.bda2 to the new government of Ho Chi Minh, who "did not thus declare but confirm Vietnam's independence in his famous address to the people in Ba Dinh square in Hanoi"[24]:12 on 1945 Sep 2.N.hvi

After the August Revolution in 1945, the French began to negotiate their return to Tonkin with both the Viet Minh and the Chinese army coming to disarm the defeated Japanese north of the 16th parallel. Ho Chi Minh was weary of the Chinese, who might stay in Vietnam permanently, signed the preliminary March 6 [1946] AccordsN.m6a1 N.m6a3 with Jean Sainteny, "commissioner of the French Republic in Tonkin and North Annam [central Vietnam],"[24]:9 to agree to let the French army under General Leclerc to enter Tonkin. On 1946 Mar 18, "General Leclerc led 1,200 troops and 220 vehicles,"[32]:90 bearing both French and Viet-Minh flags,[27]:238 N.leh "into Hanoi to the relief and delight of more than ten thousand French civilians who had gathered along Trang Tien Street to cheer and sing” the French national anthem.[32]:90 After his entry into Hanoi, "Leclerc quickly established cordial relations with Ho Chi Minh."[33]

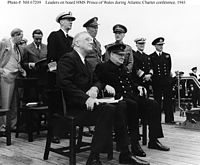

Then High Commissioner d'Argenlieu, the "abomination of Vietnam,"N.dar2 insisted to meet Ho Chi Minh on the French battleship Emile-Bertin, "bristling with guns" to impress on Ho French military power, in the Ha Long Bay on 1946 Mar 24, together with Gen. Leclerc and Jean Sainteny for a follow-up discussion stipulated by the preliminary March 6 Accords.N.hsc The key issue was to find a venue for a conference leading to a permanent agreement. While d'Argenlieu wanted to have the conference in Dalat, Cochin China (south Vietnam), Ho together with Leclerc and Sainteny wanted to meet in Paris.

In May 1946, Ho Chi Minh boarded an airplane for France.N.hif The conference at Fontainebleau, outside of Paris, failed to reach an agreement. With "nearly insoluble fundamental differences of viewpoint,"[34]:84 the main disagreements centered around the unification of the three regions, called the "three Ky," namely Tonkin (north), Annam (central), Cochin China (south Vietnam), and the independence of Vietnam, to which France only wanted to give an "autonomy."[34]:84 On 1946 August 1, D'Argenlieu undercut the Fontaineblau negotiation by calling for a "federation" conference in Dalat, giving the autonomy status to Cochin China, thus preempted the possibility of Cochin China to join a unification of the "three Ky" via a referendum as agreed to in the March 6 Accords.[34]:84 Ho told Sainteny:

Ho Chi Minh to Jean Sainteny, 1946 September ❝ Then if we must fight, we will fight. You will kill ten of my men while we will kill one of yours. But you will be the ones to end up exhausted. And in the long run, I will win! ❞ --- Sainteny 1972, Ho Chi Minh and His Vietnam.[34]:66, 89

CBS reporter David Schoenbrun interviewed Ho Chi Minh on 1946 Sep 11, the same day that a telegram was dispatched from the High Commissioner d'Argenlieu to the French Indochina Committee on the arrest of Bich on 1946 Aug 25.:N.bb

CBS Schoenbrun interviewed Ho Chi Minh, 1946 Sep 11 ❝ President Ho, how can you possibly fight a war against the modern French army? You have nothing. You've just told me, what a poor country you are. You don't even have a bank, let alone an army, and guns, and modern weapons, the French planes, tanks, napalm. How can you fight the French? ❝ And he [Ho] said: Oh we have a lot of things that can match the French weapons. Tanks are no good in swamps. And we have swamps in which the French tanks will sink. And we have another secret weapon, it's nationalism. And don't think that a small ragged band cannot fight against a modern army. It will be a war between an elephant and a tiger. If the tiger ever stands still the elephant will crush him and pierce him with his mighty tusks. But the tiger of Indochina is not going to stand still. We're going to hide in our jungles by day and steal out by night. And the tiger will jump on the back of the elephant and tear huge chunks out of his flesh and then jump back into the jungle. And after a while the mighty elephant will bleed to death. ❞

--- CBS reporter David Schoenbrun, Youtube video French involvement in Vietnam & Dien Bien Phu - 1962, time 3:10.[35]

Bich wrote about the French use of American-made napalm bombs; see Section Napalm bombs.

I AM HERE 24.11.30.

Franklin D. Roosevelt

If Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) had lived beyond 1945 Apr 12, when he died, he "would have tried to keep France from forcibly reclaiming control of Indochina, and might well have succeeded, thereby changing the flow of history,"[14]:710 meaning the First Indochina War with more than half a million deaths,N.fwc and the Second Indochina War with more than three million deaths,N.awc would be avoided; then Bich would not join the Viet Minh to fight the French colonialists.

FDR blamed European empires for wars: "European colonialism had helped bring on both the First World War and the current one, he was convinced, and the continued existence of empires would in all likelihood result in future conflagrations."[14]:46 "What is more, like Wilson, he [FDR] emerged from World War I convinced that the scramble for empire not only had set the European powers against one another and created the conditions that led to war, but also worked against securing a negotiated settlement during the fighting."[14]:47

In WWII, FDR believed that "France had ceased to exist," despite having the strongest army in Europe, [14]:27 and thought that European countries (France and Germany) could not live together peacefully: Both FDR and his Secretary of State Cordell Hull "believed that Franco-German disputes lay at the root of much of Europe's inability to maintain the peace".[14]:44

Moreover, de Gaulle's Indochina cause was hampered as FDR disliked de Gaulle's pomposity, egotism, and "his serene confidence that he represented the destiny of the French people."[14]:44 "In social interaction, de Gaulle was as austere and pompous as FDR was relaxed and jovial."[14]:44 That both de Gaulle and the Vichy government wanted to preserve the French Empire further “enhanced Roosevelt’s disdain" for de Gaulle.[14]:46 Cordell Hull was convinced that "de Gaulle was a fascist and an enemy of the United States."[14]:45

By the time of Pearl Harbor, FDR had become a "committed anticolonialist,"[14]:46 who wanted "complete independence for all or almost all European colonies",[14]:74 as evidenced by his speech in March 1941:

❝ There has never been, there isn't now, and there never will be, any race of people on earth fit to serve as masters over their fellow men.… We believe that any nationality, no matter how small, has the inherent right to its own nationhood. ❞ ---Franklin D. Roosevelt, address to White House Correspondents' Association, March 1941.[14]:72

"Roosevelt went out of his way to single out France in Indochina and often cited French rule there as a flagrant example of onerous and exploitative colonialism."[20]:51

Roosevelt's anti-colonialist speech was subsequently encoded in the third point of The Atlantic Charter,N.cac which Churchill was reluctant to agree to, worrying that it would affect the British colonies:N.chac

| The Atlantic Charter, 1941 |

|---|

| ❝ Third, theyN.tac respect the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live; and they wish to see sovereign rights and self-government restored to those who have been forcibly deprived of them; ❞ |

| ---Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill, The Atlantic Charter, August 14, 1941.[36] |

The Atlantic Charter inspired Third-World countries from Algeria to Vietnam in their fight for independence,[36] as Ho Chi Minh often referred to The Atlantic Charter in his letters to US government officials: “the carrying out of the Atlantic and San Francisco Charters implies the eradication of imperialism and all forms of colonial oppression,” wrote Ho Chi Minh to US Secretary of State James F. Byrnes in the Harry S. Truman administration on 1945 Oct 22.[37]:2 N.hac

One of Roosevelt's great war aims was to liberate the Indochinese, whom he dismissed as "a people of small stature," from the French colonialism.[22]:1

FDR envisioned a new world order in which the "four policemen," i.e., the US, the USSR, Great Britain and China, would maintain peace in the world. He discussed this concept with Stalin in Tehran in 1943.[17]:60 But failing to build up China as a great power, FDR encountered difficulties with his vision for Indochina.[17]:60

Yet, despite the "accepted wisdom" of historians prior to 2007 that (1) "Roosevelt abandoned or watered down his Indochina policy before he died," and (2) "the Truman administration built upon Roosevelt’s policy revision by endorsing the French return to Indochina," a 2007 argument was presented that "Roosevelt, though he was under pressure to abandon his policy, did not yield before he died."[17]:60

Even though US intelligence (through "intercepted Japanese diplomatic messages"[17]:65) knew about the Japanese's concern of a US invasion and their plan to topple the French colonial government in Indochina since as early as 1945 Feb 11, none of this information was passed on to de Gaulle.[17]:65 On 1945 Mar 8, the day before the Japanese coup de force, Roosevelt ordered Lt Gen. Albert C. Wedemeyer---US commander of the China Theater, which included "mainland China, Manchuria, and Indochina, plus all the offshore islands, except Taiwan," and who began his assignment at the end of 1944 Oct[20]:14 --- "not to hand over supplies---any supplies at all---to French forces operating in Asia."[17]:66

"By fuelling French and Japanese expectations of a US invasion, Roosevelt, Wedemeyer and the OSS prompted a Franco-Japanese confrontation [i.e., the Japanese coup de force on 1945 March 9], which in turn paved the way for revolution,"[22]:220 i.e., the August Revolution in 1945, the year Bich joined the Viet Minh to fight the French.

On 1945 Mar 23, FDR "wanted to know what Wedemeyer could do to arm local resistance groups opposed to French rule."[17]:67 Wedemeyer wrote in a cable in 1945 May: "When talking to the President on my last visit he explained the United States policy for FIC [French Indochina] and told me that I must watch carefully to prevent British and French political activities in the area and that I should give only such support to the British and French as would be required in direct operations against the Japanese."[17]:67 Wedemeyer "continued to carry out Roosevelt’s directives on Indochina well after the President’s death,"[22]:18 and squabbled with Lord Mountbatten, head of South-East Asia Command (SEAC), over "which commander held responsibility for military operations in Indochina."[14]:88

Mountbatten, the Supremo, asked Gen. Leclerc, who left Paris on 1945 Aug 17 on his way to reconquer Indochina under the order of de Gaulle, to first come to Kandy, Sri Lanka, SEAC headquarters.[27]:152 When Leclerc arrived on 1945 Aug 22, Mountbatten told him, "If Roosevelt had lived, you would not go to Indochina."[27]:153 N.mtl

Harry S. Truman

Truman reversed Roosevelt’s commitment to free Indochina of French colonialism, allowing the French to reconquer Cochin-china with the help of the British, leading to The First Indochina War, with Bich fighting the French.

Roosevelt had selected Truman as his Vice President because Truman was more moderate than the previous left-leaning VP Henry Wallace.[38] But Roosevelt kept Truman in the dark about foreign policies,N.tfp met Truman only six times, and only one time alone without aides. Truman did not have experience in international relations, and was kept so, particularly about the important Yalta Conference in 1945 February, where Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin discussed the new world order.[38]

After the secretive FDR (who "never wrote down, and rarely discussed, a concrete vision for the postwar world"[38]) died, "U.S. policy fell into the hands of Truman, who had no idea what Roosevelt had really wanted to achieve or how he had planned to achieve it. Over the coming three years, Truman would take this ignorance, combined with Stalin’s strategic overreach and blundering, and create the Cold War that Roosevelt had always been keen to avoid."[38]

To maintain the appearance of continuing Roosevelt’s policy regarding Indochina, as Truman "did not want to convey the impression that his [Indochina] policy was at odds with Roosevelt’s,"[17]:70 it took Truman close to two months, from the death of Roosevelt on 1945 Apr 12, until 1945 Jun 7 (the date of the telegram from Acting Secretary of State Joseph Grew, on behalf of Truman, to US Ambassador Patrick Hurley),[17]:72 N.uah to provide American officials in the Far East (US Ambassador Patrick Hurley and Gen Wedemeyer, US commander of China Theater) with "less than clear" policy regarding Indochina, "portraying change as continuity" of Roosevelt's policy of not letting the French reconquer Indochina as a colony.[17]:71

Truman's ("less than clear") US policy is described by Grew as follows: "It is the President's intention at some appropriate time to ask that the French Government give some positive indication of its intentions in regard to the establishment of civil liberties and increasing measures of self-government in Indo-China before formulating further declarations of policy in this respect."[17]:71

Under the threat of the Cold War with the Soviet Union, Truman did not want to “have a conflict with France and Britain”[17]:70 over the insistence of these countries to reconquer their lost colonies, effectively abandoning Roosevelt’s trusteeship plan for Indochina. Hurley and Wedemeyer "continued to operate in the shadow of FDR."[17]:70

As a result, "lacking clear directives from Truman, US military and intelligence agencies remained uncertain of their government's Indochina policy. Some of them therefore continued to apply Roosevelt's anti-French policy."[22]:19 French official Jean Sainteny lamented that he was "face to face with a deliberate Allied maneuver to evict the French from Indochina and that at the present time the Allied attitude is more harmful than that of the Viet-Minh."[39]:68-69 N.bq2

❝ General Wedemeyer's orders not to aid the French came directly from the War Department. Apparently it was American policy then that French Indochina would not be returned to the French. The American government was interested in seeing the French forcibly ejected from Indochina so the problem of postwar separation from their colony would be easier. . . . While American transports in China avoided Indochina, the British flew aerial supply missions for the French all the way from Calcutta, dropping tommy guns, grenades and mortars. ❞ ---Bernard B. Fall (1966), The Two Viet-Nams: A political and military analysis, p.57.[39]:57

Three months after Roosevelt's death, at the Potsdam Conference in 1945 July, the US adopted a neutral stance regarding the French return to Indochina: "The United States would not obstruct the restoration of French sovereignty, but neither would it give active backing,"[40]:112 contrary to what the British had hoped for, which was "active American support of French aims" of reconquering Indochina.[40]:111 Still, the partition of Indochina, with the Chinese in the north of the 16th parallel, and the British in the south, represented a "significant British victory," since London now had "an opportunity to reinstall a French military and administrative presence below the sixteenth parallel, a foothold that France could presumably exploit to recover the rest of the country from Chinese control."[40]:112

On the other hand, if the US had let the British control the whole of Indochina, the French would "most likely have been able to oust Ho Chi Minh's revolutionary government from Hanoi in the fall of 1945, thus immediately provoking general warfare."[24]:23 It was "the presence of a large Chinese army that allowed the Viet Minh to establish itself as the leading force in the new republic, with a legitimate claim to representing the southern part of the nation as well,"[24]:23 where Bich had joined the Viet Minh to fight the French.

- Déjà Vu: 'Americans had different dreams from the French, but followed the same footsteps.' Bernard B. Fall

French Marines wading ashore off the coast of Annam (Central Vietnam) in July 1950, using US-supplied ships, weapons, equipment. Quote by Bernard Fall in gallery title.[14]:702

War began

Two camps of historians chose two different dates for the start of the First Indochina War: Either 1945 Sep 23 (one year before the failed Fontainebleau conference in 1946 Sep), or more than a year later, 1946 Dec 19 (three months after the failed Fontainebleau conference in 1946 Sep). Of these two dates, 1945 Sep 23 is more relevant to Bich since he had been captured on 1946 Aug 25,[8] before 1946 Dec 19.

1945 Sep 23, Cochin China

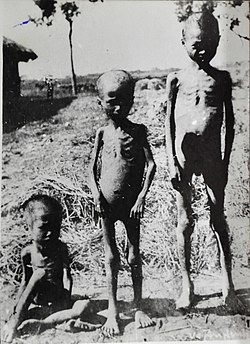

The First Indochina War started on 1945 September 23 in Cochin China (south Vietnam) with the brutal repression of the Vietnamese by some 1,400 French soldiers, who had been imprisoned by the Japanese, then freed and re-armed by British General Gracey, and who went on a rampage, beating, lynching any Vietnamese they saw on the street.[14]:115

French war correspondent Germaine Krull, who arrived in Saigon on 1945 Sep 12 with the British Gurkhas soldiers and a small group of French soldiers,N.bfa was likely the first to mark the start of the First Indochina War on this date, as she described in her "most graphic, vivid, and absorbing" reportN.mok what she had witnessed "with her own eyes":

❝ It is impossible to describe this day, which marked the beginning of the war in Indo-China. I saw everything with my own eyes - Annamites [Vietnamese] tied up, some of them tortured, drunken officers and soldiers with smoking guns. On the Rue Catinat, I saw soldiers driving before them a group of Annamites bound, slave-fashion, to a long rope. Women spat in their faces. They were on the verge of being lynched. In more distant sections I saw French soldiers come out of Annamite houses with stolen shoes and shirts… From time to time, an Annamite dwelling would burst into flame. Women and children were fleeing. That night, French soldiers strolled on the Rue Catinat, a gun on one arm, a woman on the other. I have never been so deeply ashamed as on that day of September 23rd. When I returned to the hotel, the faces of the English were expressionless and conversations stopped as I went by. I remember the horror and shame I had felt in June of 1940 when Vichy was established, but never in my life had I felt such utter sadness and degradation as on this night.

That night I realized only too well what a serious mistake we had made and how grave the consequences would be. It was the beginning of a ruthless war. Instead of regaining our prestige we had lost it forever, and worse still, we had lost the trust of the few remaining Annamites who believed in us. We had showed them that the new France was even more to be feared than the old one. ❞

---Germaine Krull (1945), Diary of Saigon, following the Allied occupation in September 1945.[41]:19

| French colonists tied up a Vietnamese, choked him, pulled his hair, and threw him onto a military truck |

|---|

| In the 1968 Documentary In the Year of the Pig, time 14:38, David Halberstam said: "... the Indochina war and all the best and most talented Vietnamese of a generation had faced, in 1946 and 1947, the alternative of the French or the Viet Minh. The best of a generation, the kind of young men who would join up the day after Pearl Harbor in this country [United States]. Are you going to fight to kick out the French, or are you going to be a French puppet? So the most talented people of a generation all signed up and the Viet Minh won this war and it was an enormously popular national war." |

This date, 1945 Sep 23, "would go down in history: Trần Văn Giàu, a key communist leader of the southern Viet Minh, announced that "the war of Resistance has begun!" Vietnam's armed struggle against the French had started. It would last nine more years."[42]:45 Giau issued the following call for armed struggle to throw out the French, addressing to his Vietnamese compatriots, including those who were working for the French colons like Bich:

❝Compatriots of the South! People of Saigon! Workers, farmers, youth, self-defense, militia, soldiers!

Last night, the French colonialists occupied our government headquarters in the center of Saigon. Thus, France began to invade our country once again.

On September 2,N.vid our compatriots swore to sacrifice their last drop of blood to protect the independence of the Fatherland:

"Independence or death!"

Today, the Resistance Committee calls on: All compatriots, old, young, men, and women, take up arms and rush to fight off the invaders. Anyone who does not have a duty assigned by the Resistance Committee must immediately leave the city. Those who remain must:

– Not work, not serve as soldiers for the French.

– Not show the way, not inform the French.

– Not sell food to the French.

– Find the French colonialists and destroy them.

– Burn all French offices, vehicles, ships, warehouses, and factories.Saigon occupied by the French must become a Saigon without electricity, without water, without markets, without shops.

Fellow countrymen! From this moment on, our top priority is to destroy the French invaders and their henchmen. Fellow soldiers, militiamen, and self-defense members! Hold your weapons firmly in your hands, charge forward to drive out the French colonialists, and save the country.

The resistance war has begun!

Morning of September 23, 1945

Chairman of the Southern Resistance Committee

TRAN VAN GIAU ❞---Trần Văn Giàu 2011, HỒI KÝ TRẦN VĂN GIÀU (XVII) [Memoirs of Tran Van Giau, Vol.17], diendan.org. Internet Archive 2023.03.27

"Thus began, it could be argued, the Vietnamese war of liberation against France. It would take several more months before the struggle would extend to the entire south, and more than a year before it also engulfed Hanoi and the north, which is why historians typically date the start of the war as late 1946 [Dec 19].[24]:xii But this date, September 23, 1945, may be as plausible a start date as any."[14]:115

I AM HERE 24.11.21. Text commented out in this section to debug references listed, but not cited.

☛ NOT DONE, TO ADD: Egm4313.s12 (talk) 15:17, 8 April 2023 (UTC)

- Brutal repression by British and French forces in Cochinchina (South Vietnam)

- Quotations from Tønnesson (2010)Template:Sfn and Donaldson (1996)Template:Sfn

1946 Dec 19, Tonkin

Resistance

After graduating in 1935 from the École nationale des ponts et chaussées, a civil engineering school, Nguyen Ngoc Bich returned home to work as a civil engineer for the colonial government at the Soc-Trang Irrigation Department until the Japanese coup d'état in Viet Nam (1945 Sep 03). Bich then joined the Resistance in the Soc-Trang base area and was appointed Deputy Commander of the Military Zone 9 (vi), established on 1945 Dec 10, and included the provinces of Cần Thơ, Sóc Trăng, Rạch Giá, together with six other provinces. Bich sabotaged many bridges that were notoriously difficult to destroy such as Cai-Rang Bridge in Can Tho --- where a street was named to honor his feats[43] N.nnbs --- Nhu-Gia Bridge in Soc Trang, etc., blocking the advance of French forces directed by General Valluy and General Nyo, who were under the general command of General Philippe Leclerc, commander of the French Far East Expeditionary Corps (Corps expéditionnaire français en Extrême-Orient, CEFEO). Between 1946 March 6, when the March 6 Accords were signed,N.m6a3 and 1946 December 19, when most historians used as the date that started the First Indochina War, in Cochinchina, the military situation did not favor the Vietnamese.

❝ Outside Saigon the various nationalist resistance groups, weakened though they were by the months of warfare with the British and French, still controlled large sections of the Cochin Chinese countryside. Ho Chi Minh proposed to General Leclerc the sending of mixed Franco-Vietnamese commissions to establish peace in Cochin China after the signing of the March 6 accord, but the General saw no reason for this in what was supposed to be French territory. When Ho sent his own emissaries to the south, they were arrested by the French who continued to regard Cochin China as a French colony, claiming a free hand there until the referendum could be held. This led to difficult local problems, as in the case of the Vietnamese emissary sent by one Vietnamese zone commander [Nguyen Ngoc Bich] to discuss a cease-fire with the local French commanding officer. The emissary was unceremoniously informed that the French expected complete capitulation—the surrender of arms and prisoners—and that this was an ultimatum. They had until the 31st of March to comply; if they failed to do so, the fighting would begin again. Before the Vietnamese left French headquarters, the French officer took his name and it was soon public knowledge that the French had put a price on his head as well as on that of his commander, Nguyen Ngoc Bich. In this particular region of Cochin China fighting resumed by the end of the month. ❞ ---Ellen Hammer (1954), The struggle for Indochina, pp. 157–158.[10]

Chester L. Cooper was an American diplomat and a key negotiator in many critical agreements in the 1950s and '60s, beginning with his involvement in the Geneva Conference on Indochina in 1954.[44] In his 2005 memoir In the Shadows of History: 50 Years Behind the Scenes of Cold War Diplomacy, "he recounted his association with a constellation of historic figures that included John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, Nikita S. Khrushchev and Ho Chi Minh".[44] N.clc Dr. Cooper N.dcc --- who acquired a deep knowledge of Vietnam history from his years in Asia, from 1941 to 1954, first working for the Office of Strategic ServicesN.hos in China, then for the CIA in 1947, and subsequently became head of the Far East staff of the Office of National Estimates in 1950[45]---devoted some three to four pages to describe Dr. Bich in his Vietnam-history book The Lost Crusade: America in Vietnam, in particular some aspects of Bich's resistance activities:

❝ As commander of the Viet Minh forces in the Delta during the late 40s, Bich became one of the most popular local heroes. During 1946 the Viet Minh hierarchy became concerned that Bich might pose a threat to the aims of the Viet Minh in the southern part of Vietnam, and by the end of that year Ho apparently decided that Bich had served his purpose in the Delta. He was "invited" to move North to become a member of the Viet Minh political and military headquarters in Hanoi. Bich was reluctant to leave his command, not only because of his desire to continue the fight against the French, but also because he felt uneasy about leaving his base of power. Nonetheless, he made his way north via the nationalist underground to Hanoi. A day or two before Bich was to report to the Viet Minh headquarters, the French discovered his hiding place near Hanoi. Since he was on the French "most wanted" list, he was subjected to an intensive and unpleasant interrogation. ❞

---Chester L. Cooper (1970), The Lost Crusade: America in Vietnam, p. 122.[2]

Joseph A. Buttinger was an ardent advocate for refugees of persecution, and a "renowned authority on Vietnam and the American war" in that country.[46] In 1940, he helped founded the International Rescue Committee, "a nonprofit organization aiding refugees of political, religious and racial persecution", and while "working with refugees in Vietnam in the 1950s, he became immersed in the history, culture, and politics of that nation".[46] His scholarship was in high demand during the Vietnam War. The New York Times described his his two-volume Vietnam-history book, Vietnam: A Dragon Embattled,[47][1] N.jbr1 as "a monumental work" that "marks a strategic breakthrough in the serious study of Vietnamese politics in America" and as "the most thorough, informative and, over all, the most impressive book on Vietnam yet published in America".[46] Joseph Buttinger wrote in Vietnam: A Dragon Embattled, Vol. 2 that Dr. Bich was "the resistance hero" whom "Diem had no success" to convince to join his cabinet:

❝ Diem left Paris for Saigon on June 24, accompanied by his brother Luyen, by Tran Chanh Thanh, and by Nguyen Van Thoai, a relative of the Ngo family and the only prominent exile willing to join Diem's Cabinet. With others, such as the resistance hero Nguyen Ngoc Bich, Diem had no success. He tried unsuccessfully to win Nguyen Manh Ha, a Catholic who had been Ho Chi Minh's first Minister of Economics but who had parted with the Vietminh in December, 1946. These men, and others too, rejected Diem's concept of government, which clearly aimed at a one-man rule. Nor did they share Diem's illusions about the chances of preventing a Geneva settlement favorable to the Vietminh. Diem apparently believed that the National Army, no longer fighting under the French but for an independent government, would quickly become effective and reduce the gains made by the Vietminh. ❞ ---Joseph Buttinger (1967), Vietnam: A Dragon Embattled, Vol.2, p. 850.N.jbr2

That Nguyen Ngoc Bich was being hunted by the French colonists was described in Joseph Buttinger's book:[47]:641

❝ [Note] 9. Miss Hammer cites the case of an emissary sent by Nguyen Ngoc Bich. The French took down his name when he came to their headquarters to negotiate a cease-fire, and "it was soon public knowledge that the French had put a price on his head as well as on that of his commander, Nguyen Ngoc Bich" (ibid., p. 158). ❞ ---Joseph Buttinger (1967), Vietnam: A Dragon Embattled, Vol.1, p. 641.N.pbh

Napalm bombs

- French use of American-made napalm bombs

French Napalm bomb exploded over Vietminh force. 1953 December. This image during the (French) First Indochina War, conjuring up the horrific destruction of the Napalm on the human flesh,[48] N.ng2 portended what was to come more than ten years later during the (American) Second Indochina War with even more deadly advanced Napalm technology.

On the French use of American-made napalm bombs, Bich wrote that the Viet Minh stopped following the advice of Chinese tacticians in launching large-scale mass attacks once many of their soldiers died by French napalm bombs. They switched from the costlier manufacturing of arms to the less expensive manufacturing of hand grenades, which can be used against light battalions to seize their arms.[3]

Publications

- Nguyen-Ngoc-Bich (March 1962), "Vietnam—An Independent Viewpoint", The China Quarterly 9. Retrieved on 18 Feb 2023, pp. 105–111. See also the contents of Volume 9, which included the articles of many experts on Vietnam history and politics such as Bernard B. Fall, Hoang Van Chi, Phillipe Devillers (see, e.g., his classic 1952 book Histoire du Viet-Nam in Section References and French French Cochinchina, Ref. 42), P. J. Honey, Gérard Tongas (see, e.g, J'ai vécu dans l'Enfer Communiste au Nord Viet-Nam, Debresse, Paris, 1961, reviewed] by P. J. Honey), among others.

Bich's 1962 paper, summary

In 1962, Dr. Bich laid out an argument to avoid the subversion war by North Vietnam to conquer rice from South Vietnam to solve its famine problem due to low yields in agricultural production using archaic methods and due to the failed agrarian reform. His main points were (1) South Vietnam should have a truly liberal democratic government, (2) the South should establish commercial relations with the North to help solve the said famine problem, (3) the South should maintain a non-aligned neutrality that would prevent interference from the North, (4) the South would peacefully negotiate with the North toward a progressive reunification. Below is a more detailed summary of his article, looking back from more than 60 years later. As a result, past tense is used in this summary to describe long-past events, instead of the sometimes present tense used in the original article. The full article translated into French is available in the document Nguyen Ngoc Bich (1911–1966): A Biography.N.bb2

Vietnam, China, and USSR

Contrary to the belief of the Western world (that the Vietnamese generally disliked, and had an inferiority complex against, the Chinese), the Vietnamese tended to be too proud of their history and victories against the Chinese and Mongol invaders over the centuries.

Aware of the Chinese historical "fierce expansionism", an important question for North and South Vietnam was how to safeguard the future of Vietnam as a whole country.

While South Vietnam tried to forcibly assimilate Chinese immigrants and their descendants, North Vietnam adopted a "more subtle attitude", moving from "fears" during the Chiang Kai-shek era to "solidarity and friendship" after the communist had won in 1949.

The Geneva agreements, while satisfying for China, left the North Vietnamese to be content with the prospect of reunifying with South Vietnam upon an election. After the failure of the agrarian reform, there was a concern of the presence of many Chinese soldiers and civilians in North Vietnam. To keep Chinese economic aid flowing, Ho Chi Minh initially maintained a balance between Peking (Beijing) and Moscow, but subsequently tilted toward Moscow after Peking admitted that it could not help carry out a semi-heavy industrialization. In September 1960, Le Duan, then Secretary-General of the Party, put forward a three-point program: (1) Support Moscow in any Sino-Soviet dispute, (2) Five-year plan (1961–1965) to socialize North Vietnam, (3) Progressive and peaceful reunification of the two Vietnams.

Le Duan: Reconquer the South

With the nomination of Le Duan—who led the struggle for independence in South Vietnam for a long time and knew the South more than anyone else—as First Secretary of the Party, North Vietnam began to undertake the reconquest of the South, with the first step being to eliminate the Ngo Dinh Diem regime and the American influence in the South. There were deeper motives.

Communist pragmatism

"The most striking feature of the Vietnamese Communist leadership was its outstanding spirit of realism, even pragmatism." They continuously and critically reexamined facts so that a lesson could be drawn for every action and every happening to avoid past mistakes. By doing so, they tended to imitate or to repeat past actions that were proven successful, and lacked imagination and open-mindedness to create new solutions to tackle new challenges.

For example, they stopped following the advice of Chinese tacticians in launching large-scale mass attacks once many of their soldiers died by French napalm bombs. They switched from the costlier manufacturing of arms to the less expensive manufacturing of hand grenades, which can be used against light battalions to seize their arms. They bred dogs, instead of pigs, as a source of meat since dogs produced two litters of young each year, while pigs produced only one.

Rapid industrialization

A deeper motive to swing closer to Moscow was to develop a rapid industrialization to raise the standard of living to avoid complaints about dictatorship and restriction of freedom, and also the "dreaded spectre of becoming a mere satellite state".

The targets of the Five-Year Plan were "extremely optimistic". In the old French Indochina, "great leaps forward" in economics were achieved in some sectors, such as a 400% increase in plantation area, 150% increase in the number of workers in industrial establishments, in spite of World War I. Now, there was an abundance of labor due to high unemployment. The planned industrial projects could be completed if foreign aid maintained the same rhythm and agricultural production was adequate.

Agricultural risk of failure

It was doubtful, however, that the target of growing agricultural production by 61% over five years could be achieved due to low yields resulting from the archaic methods of cultivation, the old system of sub-letting land, the difficulty of cultivating new land, the discontent among the peasants, and the disastrous agrarian reforms and its consequence. Hunger had become endemic, and China could not come to the rescue because of her own problems. Rice had to be smuggled from the South to the North.