Email system/Citable Version: Difference between revisions

imported>Hayford Peirce (created approved article) |

imported>Hayford Peirce m (Protected "Email system": Article version approved [edit=sysop:move=sysop]) |

(No difference)

| |

Revision as of 16:18, 3 October 2009

- See also: Email processes and protocols

The email system is the network of computers handling electronic mail (email) on the Internet. This system includes user machines running programs that compose, send, retrieve, and view messages, and agent machines that are part of the mail handling system. Like other complex systems, the email system is best explained by looking separately at different perspectives, applying the principle of separation of concerns. There are two coequal ways of looking at email systems - the administrative perspective (who does what), and the process perspective (how it flows). The administrative perspective presented in this article is the simplest. It can be understood without any technical background. The process perspective presented in "Email processes and protocols" provides more technical depth, and should be understood by anyone involved in the design or operation of email systems.

In the process perspective, the mail handling system can be modeled as a sequence of relay processes, each temporarily storing the message, performing some specialized function, and passing it on to the next relay using the SMTP protocol.[1] You can tell how many relays handled a message by looking at the lines labeled "Received:" in the message header. There should be one for each relay. Relays are not our focus in this article, however. We can ignore them in higher-level models, just as routers and physical links can be ignored in discussing relays.

In the administrative perspective, the principal entities are actors, their roles, and their relationships. Who are the actors in a typical email system? What are their roles and responsibilities in handling the mail? What are their relationships with each other? What are their motivations? How can we build better security systems? A basic understanding of the administrative perspective should help answer these questions. This article provides that understanding.

System architecture

|

Actors and Roles: |

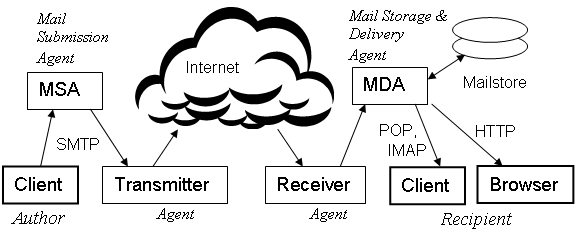

Figure 1 shows an ideal system with the machines grouped into functional blocks. In this diagram, we have named the blocks by their role in processing a message. The actors (users or agents) are shown in italic text. The MSA role, for example, is played by a Mail Submission Agent, which performs all functions related to message submission. In this ideal system, we have assigned each role to a different actor. In real systems, however, an actor can have multiple blocks, a block can have multiple machines, and a machine can host multiple relays running as independent daemon processes.

A small Internet Service Provider (ISP) might perform the roles of MSA/Transmitter using two relays running on one machine. An agent performing the role of Transmitter might have a dozen relays, operating in parallel to handle a large mailflow, or widely dispersed to serve users all over the world. A Mail Delivery Agent might have a process dedicated to managing a large mailstore, another running a POP/IMAP server, and another providing webmail via HTTP to the Recipient's browser.

There are many other possibilities. We might add a Forwarder between the Receiver and the MDA. We might show contractual relationships between the agents or their affiliation with particular networks.[2] A diagram like Figure 1 could get quite complex. A shorthand notation will allow us to show the relevant networks, actors, roles, and relationships. Here is a basic system with four actors (two users and two agents), organized as two networks:

|--- Sender's Network ---| |-- Recipient's Network -|

/

Author ==> MSA/Transmitter --> / --> Receiver/MDA ==> Recipient

/

Border

To understand a mail handling system, including its security vulnerabilities, we need to focus on the roles and responsibilities of each actor and the relationships between them. The double arrow shows a direct relationship between actors (e.g. a contract between the Author and his ISP). The single arrow shows only the direction of mail flow. There is no relationship between agents across the Border to the open Internet. The / shows multiple roles being played by one actor. Using these diagrams, we can model almost any system, and include a lot of detail on relationships, but not lose the simplicity of Figure 1. The elements of the model (actors' roles) are the fundamental building blocks. See Email agents for more example systems.

Here is an extension of the basic system, adding a Forwarder role, played by the same actor as the Receiver. Both the Receiver/Forwarder and the MDA have a direct relationship with the Recipient, so they have an indirect relationship (wavy arrow) with each other. These details are important in discussions of authentication protocols.

|-------- Recipient's Network ---------|

/

--> / --> Receiver/Forwarder ~~> MDA ==> Recipient

/

Border

If we wonder why email continues to be such an insecure system, we can study this last example. An MDA is quite frequently a Receiver/MDA that is unaware when an incoming message has been forwarded. If the MDA runs the most common authentication checks on the incoming message, it may be rejected as a forgery. The problem is that the Transmitter's domain name no longer correlates with the IP address seen on the incoming connection from the Forwarder.

This is a good example of how difficult it is for security protocols to keep up with evolving system designs and changing environments. Forwarding is much more prevalent now than when the most common email authentication protocols were designed. We can no longer dismiss Forwarding as just an "edge case". It is important for a user who changes jobs or ISPs, and would like to continue receiving mail at her old address.

Message handling

Let's follow a message from start to finish. The scenario begins with an Author composing a message using a mail client on a home computer. There are numerous mail clients available, just like there are many web browsers to choose from. In fact, many web browsers now include a mail client, or at least a mechanism to invoke the user's preferred client when he clicks a mailto: link in a webpage.

When the Author clicks SEND, his mail client connects to an MSA machine at his ISP. A key responsibility of the MSA is to authenticate the Author. This can be done with a password, by assigning the client machine a static IP address, or by having the client connect through the MSA's local network, not through the Internet. If it is necessary to connect through the open Internet, use of a special TCP port 587 helps to segregate requests for an authenticated connection from the flood of fraudulent attempts on port 25. After authentication, the message is transferred using SMTP.

Most large ISPs operate their own transmitter relays, but smaller companies, and organizations with a lot of bulk mail, often subcontract this specialized role to another agent. Such agents advertise their services under the name "SMTP Relay", but in this article we will use the more specific term Transmitter when we mean a role or agent, and transmitter relay when we mean the relay at the sender's side of the Border.

The Transmitter's responsibilities include prevention of outgoing spam, and providing some means to prove their identity to unrelated Receivers. It isn't enough to say "Hello, this is trustme.com". Any criminal can do that, and identity fraud has become a major problem on the Internet. The Transmitter must provide some "out-of-band" data using a service like DNS that is more secure than email. DNS records can be used to publish a public key, a list of IP addresses, or some other data that the Receiver can use to run one or more authentication methods.

The Receiver's responsibilities include a number of functions we might call "border defense" – blocking Denial of Service (DoS) attacks, authenticating the sender, and various spam-filtering strategies, including whitelisting, blacklisting, statistical analysis of message content, and use of heuristic rulesets that have proven effective in separating spam from legitimate mail. Border defense should be done at the Border. Loss of mail due to violations of this principle is common. A forwarded message can look like a forgery, and then the Forwarder has a tough choice – drop the message with no notice to the alleged sender, or send the notice and risk being reported for "bounce spam".

The problems with mis-configured mail systems can be avoided if all actors understand their roles and responsibilities. When a Recipient sets up forwarding from his old Receiver/Forwarder to his new MDA, he should make sure that the Forwarder is whitelisted by the MDA. Forwarders should make sure that Recipients (non-expert users) understand this. MDAs should understand that forwarding is a common need, and make it easy for Recipients to whitelist their Forwarders.

Notes

- ↑ Do not confuse SMTP Relays with routers or packet switches. In this cluster of articles, Relay will always mean an SMTP relay. Relays use SMTP/TCP/IP, and the functionality of routers is entirely encapsulated within the IP layer of this protocol stack. We can ignore routers in this discussion. They are "transparent" to SMTP.

- ↑ Networks of routers and links are organized into Autonomous Systems. As with routers, however, it is much simpler to think of this layer as transparent to the level we are modeling (even if the actors in our model happen to be also network owners). This is a frequent point of confusion, particularly for people who would like to hold network owners responsible for the content of the messages they carry.