Aminostatic hypothesis: Difference between revisions

imported>Ashleigh Fraser No edit summary |

imported>Ashleigh Fraser No edit summary |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

'''{{Image|Indirect fixed.png|right|350px|Indirect Pathways.}} | '''{{Image|Indirect fixed.png|right|350px|Indirect Pathways.}} | ||

Experimental evidence agrees with the aminostatic hypothesis that increased amino acid levels in the serum cause a decrease in food intake. Studies have been undertaken in order to understand the neural mechanisms that cause this. It has been found that amino acids obtained from the diet generate post-prandial signals which affect food intake as well as gastric motility and pancreatic secretions. These signals activate specific brain areas in one of two ways: | Experimental evidence agrees with the aminostatic hypothesis that increased amino acid levels in the serum cause a decrease in food intake. Studies have been undertaken in order to understand the neural mechanisms that cause this. It has been found that amino acids obtained from the diet generate post-prandial signals which affect food intake as well as gastric motility and pancreatic secretions. These signals activate specific brain areas in one of two ways: | ||

1) Indirectly though vagus-mediated pathways | <br />1) Indirectly though vagus-mediated pathways | ||

2) Directly after their release into the peripheral blood | <br />2) Directly after their release into the peripheral blood | ||

(The indirect and direct pathways are summarised in the figures.) | <br />(The indirect and direct pathways are summarised in the figures.) | ||

In indirect signalling pathways the dietary protein and amino acids present in the small intestine act on chemoreceptors on the mucosal enteroendocrine cells to cause the release of several hormones. Cholecystokinin acts on low affinity receptors on the vagus nerve which project to the nucleus of solitary tract in the brainstem to give anorexigenic effects. Peptide YY acts in two different ways through targets in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus. It activates the mammalian target of rapamycin to increase α-MSH which increases anorexigenic effects at the same time as suppressing AMPK phosphorylation to decrease neuropeptide Y and agouti related peptide and cause a decrease in orexigenic effects. | <br />In indirect signalling pathways the dietary protein and amino acids present in the small intestine act on chemoreceptors on the mucosal enteroendocrine cells to cause the release of several hormones. Cholecystokinin acts on low affinity receptors on the vagus nerve which project to the nucleus of solitary tract in the brainstem to give anorexigenic effects. Peptide YY acts in two different ways through targets in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus. It activates the mammalian target of rapamycin to increase α-MSH which increases anorexigenic effects at the same time as suppressing AMPK phosphorylation to decrease neuropeptide Y and agouti related peptide and cause a decrease in orexigenic effects. | ||

[[User:Ashleigh Fraser|Ashleigh Fraser]] 16:16, 25 October 2011 (UTC) | [[User:Ashleigh Fraser|Ashleigh Fraser]] 16:16, 25 October 2011 (UTC) | ||

Revision as of 12:02, 31 October 2011

For the course duration, the article is closed to outside editing. Of course you can always leave comments on the discussion page. The anticipated date of course completion is 01 April 2012. One month after that date at the latest, this notice shall be removed. Besides, many other Citizendium articles welcome your collaboration! |

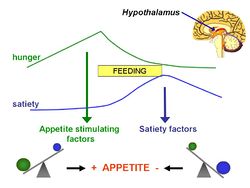

In 1956, Mellinkoff proposed the aminostatic hypothesis, stimulated by the observation that when normal individuals ingest protein, appetite diminishes as the serum amino acid concentration rises and vice versa.[1] He believed this was due to a satiety centre in the brain, sensitive to serum amino acids levels, that caused a suppression of hunger once the serum levels reached a certain point.

Experimental Evidence

-experimental evidence has agreed with the aminostatic hypothesis -they have found that high protein diets act on satiety and thermogenesis

Science behind the theory

Experimental evidence agrees with the aminostatic hypothesis that increased amino acid levels in the serum cause a decrease in food intake. Studies have been undertaken in order to understand the neural mechanisms that cause this. It has been found that amino acids obtained from the diet generate post-prandial signals which affect food intake as well as gastric motility and pancreatic secretions. These signals activate specific brain areas in one of two ways:

1) Indirectly though vagus-mediated pathways

2) Directly after their release into the peripheral blood

(The indirect and direct pathways are summarised in the figures.)

In indirect signalling pathways the dietary protein and amino acids present in the small intestine act on chemoreceptors on the mucosal enteroendocrine cells to cause the release of several hormones. Cholecystokinin acts on low affinity receptors on the vagus nerve which project to the nucleus of solitary tract in the brainstem to give anorexigenic effects. Peptide YY acts in two different ways through targets in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus. It activates the mammalian target of rapamycin to increase α-MSH which increases anorexigenic effects at the same time as suppressing AMPK phosphorylation to decrease neuropeptide Y and agouti related peptide and cause a decrease in orexigenic effects.

Ashleigh Fraser 16:16, 25 October 2011 (UTC)

Use as a method of weight loss

Obesity is everywhere. Around 33% of American adults and 17% of children are obese (A). In the UK, the statistics are not looking much brighter with 25% of adults and 10% of children showing signs of obesity. It has been proposed in the UK that 60% of men, 50% of women and 25% of children will become obese by 2050 if no preventative measures are taken (B). This growing prevalence of obesity needs a solution. Many hypotheses regarding different weight loss diets have been proposed. So how can the aminostatic hypothesis be used for treatment? Perhaps a high protein diet is the answer. Lisa Robertson 15:37, 25 October 2011 (UTC)

- What does the diet consist of? Benefits of high protein diet with supporting evidence (2,3,7,8,10). Animal/veg protein best? Lisa Robertson 15:37, 25 October 2011 (UTC)

Limitations

-are there any downsides to a high protein diet?

-appetite is a feeling so different participants in experiments may report it differently and so results may not be completely accurateAshleigh Fraser 15:34, 25 October 2011 (UTC)

- Consequent effects on renal function. Usually low carb diet is needed along with HP diet to gain full beneficial effects (subjects more satisfied).

Conclusion

- Future studies, maybe more into long term effects of diet. Any drugs that may interact with pathways? Lisa Robertson 15:44, 25 October 2011 (UTC)

References

- ↑ Mellinkoff SM et al. (1956) Relationship between serum amino acid concentration and fluctuations in appetite J Appl Physiol 8:535-8 PMID 13295170

(A)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). U.S Obesity Trends. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/trends.html. Last accessed 25th Oct 2011.

(B)Department of Health. (2011). Obesity. Available: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publichealth/Obesity/index.htm. Last accessed 25th Oct 2011.